Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

Table of Contents

About The Book

The instant New York Times bestseller from Chris Cleave—the unforgettable novel about three lives entangled during World War II, told “with dazzling prose, sharp English wit, and compassion…a powerful portrait of war’s effects on those who fight and those left behind” (People, Book of the Week).

London, 1939. The day war is declared, Mary North leaves finishing school unfinished, goes straight to the War Office, and signs up. Tom Shaw decides to ignore the war—until he learns his roommate Alistair Heath has unexpectedly enlisted. Then the conflict can no longer be avoided. Young, bright, and brave, Mary is certain she’d be a marvelous spy. When she is—bewilderingly—made a teacher, she finds herself defying prejudice to protect the children her country would rather forget. Tom, meanwhile, finds that he will do anything for Mary.

And when Mary and Alistair meet, it is love, as well as war, that will test them in ways they could not have imagined, entangling three lives in violence and passion, friendship, and deception, inexorably shaping their hopes and dreams. The three are drawn into a tragic love triangle and—as war escalates and bombs begin falling—further into a grim world of survival and desperation.

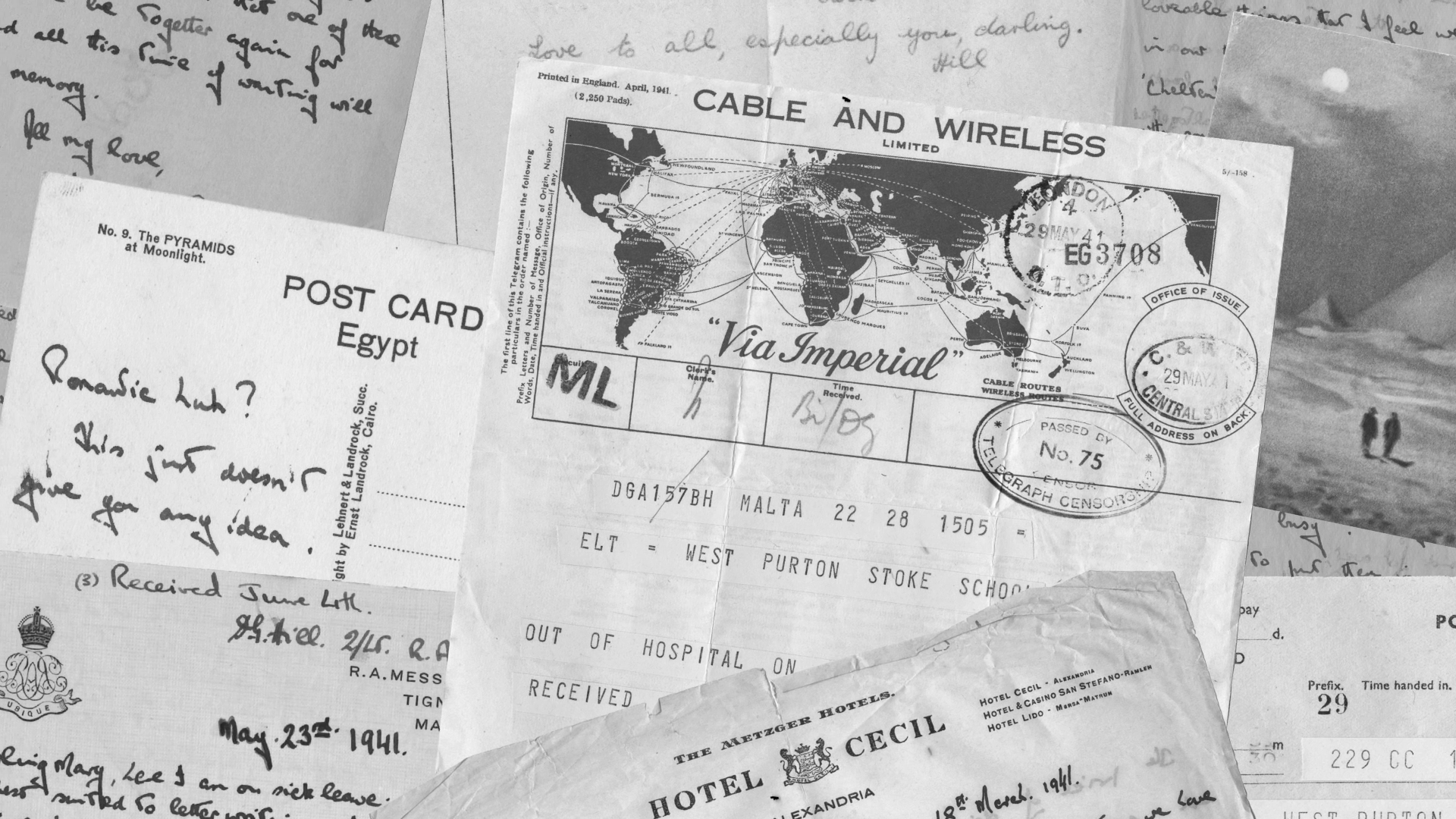

Set in London during the years of 1939–1942, when citizens had slim hope of survival, much less victory; and on the strategic island of Malta, which was daily devastated by the Axis barrage, Everyone Brave is Forgiven features little-known history and a perfect wartime love story inspired by the real-life love letters between Chris Cleave’s grandparents. This dazzling novel dares us to understand that, against the great theater of world events, it is the intimate losses, the small battles, the daily human triumphs that change us most.

London, 1939. The day war is declared, Mary North leaves finishing school unfinished, goes straight to the War Office, and signs up. Tom Shaw decides to ignore the war—until he learns his roommate Alistair Heath has unexpectedly enlisted. Then the conflict can no longer be avoided. Young, bright, and brave, Mary is certain she’d be a marvelous spy. When she is—bewilderingly—made a teacher, she finds herself defying prejudice to protect the children her country would rather forget. Tom, meanwhile, finds that he will do anything for Mary.

And when Mary and Alistair meet, it is love, as well as war, that will test them in ways they could not have imagined, entangling three lives in violence and passion, friendship, and deception, inexorably shaping their hopes and dreams. The three are drawn into a tragic love triangle and—as war escalates and bombs begin falling—further into a grim world of survival and desperation.

Set in London during the years of 1939–1942, when citizens had slim hope of survival, much less victory; and on the strategic island of Malta, which was daily devastated by the Axis barrage, Everyone Brave is Forgiven features little-known history and a perfect wartime love story inspired by the real-life love letters between Chris Cleave’s grandparents. This dazzling novel dares us to understand that, against the great theater of world events, it is the intimate losses, the small battles, the daily human triumphs that change us most.

Reading Group Guide

Get a FREE ebook by joining our mailing list today! Plus, receive recommendations for your next Book Club read.

By clicking 'Sign me up' I agree to the Terms of Use and acknowledge the Privacy Policy and Notice of Financial Incentive. Free ebook offer available to NEW US subscribers only. Offer redeemable at Simon & Schuster's ebook fulfillment partner. Must redeem within 90 days. See full terms and conditions and this month's choices.

This reading group guide for Everyone Brave is Forgiven includes an introduction, discussion questions, ideas for enhancing your book club, and a Q&A with author Chris Cleave. The suggested questions are intended to help your reading group find new and interesting angles and topics for your discussion. We hope that these ideas will enrich your conversation and increase your enjoyment of the book.

Introduction

It’s 1939, and the world is at war. Within an hour of hostilities being declared in Britain, Mary, a headstrong young socialite, volunteers to serve. She is assigned to teach children who have been rejected by the countryside to which they were evacuated. It is in this role that Mary meets Tom, an education administrator in her school district.

Their professional relationship quickly becomes personal. But when Mary meets Alistair, Tom’s best friend who has enlisted, the three are drawn into a love triangle that they must navigate while trying to survive an escalating war.

Everyone Brave is Forgiven is a sweeping epic with the same kind of unforgettable characters and scenes that made Chris Cleave’s #1 New York Times bestselling novel Little Bee a book club favorite. It is a stunning examination of what it means to love, lose and remain courageous.

Topics & Questions For Discussion

1. Both Mary and Alistair sign up to be part of the war effort almost immediately after war is declared. What are their motivations for doing so? How does each of them serve? Why is Mary surprised by her assignment?

2. When Mary first begins spending time with Tom, she describes him as “Thoughtful. Interesting. Compassionate.” (p. 41) What did you think of him? Discuss Mary’s relationship with Tom. Are the two well suited for each other? Why, or why not?

3. In a letter, Mary writes, “I was brought up to believe that everyone brave is forgiven, but in wartime courage is cheap and clemency out of season.” (p. 245) Why do you think Chris Cleave chose to take the title of his novel from this line? Does your interpretation of the title change when you read it in the full context of the quote? In what ways?

4. Mary’s student Zachary makes a big impression on her. Why? Discuss their relationship. Why does Mary write to Zachary after he has been evacuated to the countryside? How do her letters help both of them?

5. While Alistair is on leave, he returns to London and finds “there was a new way of moving that he could not seem to weave himself into.” (p. 100) Why does Alistair have difficulty adjusting to life in London? Why does Alistair put off seeing Tom? Do you think he is right in doing so? Explain your answer.

6. Early in the novel, while Mary is with Tom, she is “thinking how much she was enjoying the war.” (p. 86) Why might Mary enjoy the war? What new freedoms are afforded to her in wartime?

7. During one of her conversations with her mother, Mary notices that “There was a sadness in her mother’s eyes. Mary wondered whether it had always been there, becoming visible only now that she was attuned to sorrow’s frequency.” (p. 236) Describe Mary’s relationship with her mother. Is Mary’s mother supportive? Explain your answer. Why might Mary’s experiences during the war make her more “attuned to sorrow’s frequency”? Do these experiences help Mary better relate to her mother? Why, or why not?

8. Alistair tells Mary “Nobody is brave, the first time in an air raid.” (p. 164) How do each of the main characters react the first time that they experience an air raid? Were any of them brave? In what ways? Were you surprised by the way any of them reacted to the bombs?

9. When Mary meets with Cooper to discuss going back to work, she tells him “We needn’t put this city back the way we found it.” (p. 228) What prompts Mary to make her comment and what does she mean by it? How has life in London changed as a result of the war? Have any of those changes been positive? Why might Mary be reluctant to return to the status quo?

10. Explain the significance of Tom’s jar of blackberry jam. When Alistair is injured, he worries that “if he opened it, the dust would get into everything he minded about.” (p. 302) What does the jam represent and why doesn’t Alistair open the jar? Is Simonson right to think that “to eat the jam would be a betrayal.” (p. 393) Why? Think about your own belongings. Do you own anything like the jam jar that has special significance? Tell your book club about it.

11. Mary tells Alistair “My mother thinks [happiness] isn’t even a word, in wartime.” (p. 416) Do you think Mary’s mother is right? Why, or why not? Are there any moments of happiness in Everyone Brave is Forgiven? What are they? Discuss them with your book club.

12. What were your initial impressions of Hilda? Did they change as you learned more about her? If so, why? Discuss Hilda’s friendship with Mary. Do you think the women are good friends to each other? Explain your answer.

13. While Alistair is on leave, he, Tom, Mary and Hilda go to see Zachary’s father’s show at the Lyceum. How does each of them react to the show? Does this give you any insight into their characters? Why is Mary ashamed to go over and say hello to Zachary’s father during the interval?

14. After seeing the effects of one of the air raids, Mary “knew, now, why her father had not spoken of the last war, nor Alistair of this. It was hardly fair on the living.” (p. 268) What does Mary see that leads to her have this insight? What effect does not speaking of his experiences in war have on Alistair?

Enhance Your Book Club

1. In describing Mary, Tom tells Alistair, “She might be the only person in this city apart from you and me who understands there are many ways to serve.” (p. 32) Aside from enlisting, what other ways are there to assist in the war effort? Would you have helped in any of the ways that Mary does? Which ones appealed most to you? Why?

2. One of Mary’s first duties as a schoolmistress is to assist in evacuating the children in her class to the countryside. Learn more about the London Evacuation by visiting the Imperial War Museum’s interactive site: http://www.iwm.org.uk/history/the-evacuated-children-of-the-second-world-war. Discuss what you learn with your book club. Why might families choose to opt out of the evacuation?

3. Prior to enlisting, Alistair works as an art restorer at the Tate. On a visit back to London, he visits the museum with Mary. When they arrive “they saw that the bombing had blown its roofs off.” (p. 415) Visit the Tate’s online archive to see photos of the bomb damaged museum: http://www3.tate.org.uk/research/researchservices/archive/showcase/results.jsp?subject=266. Then, take a virtual tour of the museum’s collections to learn more about the types of art that Alistair might have restored: http://www.tate.org.uk/

4. To learn more about Chris Cleave, read reviews of Everyone Brave is Forgiven and his other bestselling books, and to connect with him online, visit his official website at http://chriscleave.com/ or join him on Twitter @chriscleave.

A Conversation With Chris Cleave

You’ve written several critically acclaimed novels, including the #1 New York Times bestseller Little Bee. Given the success of your earlier books, did you feel any added pressure when writing Everyone Brave is Forgiven? If so, how did you deal with it while you were writing?

The pressure is huge but that’s a useful problem to have. The only way I know to deal with pressure is to be more ambitious with each novel: to go deeper into the research, to reach higher with the writing and to add another layer to the psychological complexity of the characters. Sometimes I fail spectacularly, but that risk is inherent because I’m always trying to split the difference between the level I’ve reached and some platonic perfect novel. If you look at it that way, everything you’ve done so far is only a foundation, rather than an achievement in itself. This means you never step into the trap of thinking “How do I repeat those successes”? Instead you can say to yourself, with honesty: “I’m not even halfway to perfection yet—how shall I begin?”

In your author’s note you write “If you will forgive the one piece of advice a writer is qualified to give: never be afraid of showing someone you love a working draft of yourself.” (p. C) Have you learned any other lessons from writing? Can you share them with us?

I’ve learned that real life is more mysterious, frightening and fragile than anything one can make up. I’ve learned that real life doesn’t think freakish coincidences are a hackneyed plot device. Neither does real life shy away from destroying someone just because he or she is a sympathetic character.

Gloriously, I’ve also learned that people you meet in real life are very unrealistic. The marvelous problem for fiction is to capture this preposterous, implausible and blazingly eccentric life, and to put it in a cell overnight, to sober it up until it reads believably on the page. That’s what a novelist is: I’m not a creating god, I’m reality’s jailor.

Your descriptions of London during the blitz are incredibly vivid. What kind of research did you conduct to get those scenes right?

I did something louche and unfashionable: I talked with older people. I belong to the last generation of writers who can listen to elders who lived through WWII, either on the home front or as prisoners or combatants. I felt that it was important to listen to them while they were still with us to tell the tale.

Everything else, I could—and did—research in libraries and sound archives. I spent a year in dusty London basements, reading through evacuation records and logistics lists. I know how many cardboard coffins London ordered and how many it used on each night of the Blitz. I know how much an artificial leg cost to make and who produced the best ones. I even know the weights and tail fin configurations of the bombs that were most likely to cause the amputations in the first place.

In truth, I could learn far more about the war picture, both microscopic and panoramic, than anyone who lived through it could possibly have known at the time—but all of that is absolutely nothing without the life that my elderly interviewees breathed into the novel. Because what you don’t find in archives is absence: the lack of certainty about the courses of love and war, the feeling of not knowing the ending. I was—I am—in awe of the veterans I spoke with. When I look at the novel now, it seems to me that the story is mine but the fear is theirs.

In Everyone Brave is Forgiven, the action alternates between life in London during WWII and on the front. Was it difficult to change from the war front to the home front while you were writing? Can you tell us about your writing process?

While writing I thought of the novel as a tale of two sieges. Both London and Malta were effectively blockaded, and so each was a perfect pressure cooker in which my characters’ freedoms were sealed. My strategy was very simple: to respect the absolute containment of my two theatres, while obsessing about the one thin, fragile connection between them: the bridge made of letters.

What you notice when you spend several years on a project like this, and train yourself to think as your novel’s subjects thought, is what a different species they were from us. I have limited patience with people who assure us that our ancestors were “just like us.” No. By comparison, we are neurotic and fallen. We have a whimpering need to reassure ourselves that we are important and loved, through constant high-frequency, low-intensity interactions on all available channels. Our ancestors, by contrast, maintained radio silence and used rationed ink and paper. Their letters had to say more between the lines than on them.

So, my writing process was to look at a photo of my grandparents every morning before I sat down at my desk, and simply to remind myself that I was writing about people who were braver than me.

Is there anything that has been particularly rewarding about publishing Everyone Brave is Forgiven?

I’ve been glad to see the way people are using the book as a lens on how we live now. I think that’s a novelist’s job: to provide a new place for the reader to stand, from which the view back towards home is different. With my first three novels, Incendiary, Little Bee and Gold, I did this by writing characters who lived at the extremities of the contemporary experience. With Everyone Brave, I’ve gone back in time to get the same shift of perspective.

As Alistair struggles to come up with a reply to Mary, he muses that “in the history of the world there was not one example of a man ever having written a satisfactory letter to a woman who mattered to him.” (p. 247) Do you agree? Can you tell us a little about the letters that your grandfather, David, wrote to your grandmother? Did you draw any inspiration from those letters when writing Alistair’s?

I’m with Alistair on this one (although of course we could both be wrong). My grandfather’s letters to my grandmother were at their best when they were funny, and in this they were a great inspiration. I think it’s the one way in which a love letter can reduce to nothing the distance between two people: the laughter it can produce is as real and unfiltered as if the writer and the reader were sitting side by side. Everything else—an enclosed photo, a promise of intimacy, a poem (god forbid)—is only a proxy for togetherness, whereas laughter is the thing itself. I don’t know how two humorless people could ever manage to fall in love by mail. That really would be pushing the envelope.

In Everyone Brave is Forgiven, it’s clear that life on the home front is just as dangerous as life on the war front and survival cannot be taken for granted in either setting. Did you know which characters would make it through the war when you began writing?

That’s a terrific question. No, I never plan. I do a lot of research instead and then just start writing. I didn’t know which characters would survive, any more than they did. I think that was important. There are three likeable people in the book who are killed unexpectedly, and the reader might be surprised to know that for each of these I wrote the character several chapters further into the story than we see in the final version. Then I went back on an impulse and killed them, arbitrarily, in mid-sentence. This made for a lot of unexpected writing work, but that’s war: it doesn’t wait for a moment that’s convenient to the plot. In this way I created randomness and chaos that gives the novel a measure of realism, I hope.

What is your favorite moment in the book?

After poor Hilda’s face has been cut to ribbons by windshield glass, and she and Mary get high in the kitchen because they can’t deal with it any other way. Mary is busy fixing Hilda’s hair for her, and the kettle screams because the two friends can’t.

What do you like your readers to take away from Everyone Brave is Forgiven?

I admire my readers—I’ve met a great many of them now—and I would never presume to tell such people what to take away from one of my books. We bring ourselves into any story, and each of us is so different—that’s the mysterious thing about humans (and also the reason they’re worth writing about). A young person coming to Everyone Brave might not have read much about WWII yet, and so the book will be an interesting historical primer for them—certainly I’ve tried to make it accurate and readable. Someone older might have served in the war themselves, or might have close family who were involved—and in that case they’ll read the book through a more intimate lens, and the book’s images will help to surface their own memories. In any case my hope—as with all of my books—is that it will be the catalyst for some interesting discussions between readers and their friends and families. I operate on the principle that a book is small and a reader is big.

Are you working on anything now? Can you tell us about it?

I’m working all the time, but only one in four or five of my projects ever becomes a finished novel. My strongly held conviction is that there should be a prestigious literary prize for throwing away promising novels. It would be called the Phewlitzer—as in “Phew, am I glad we never had to read Chris Cleave’s novel about Noah’s wives.”

Introduction

It’s 1939, and the world is at war. Within an hour of hostilities being declared in Britain, Mary, a headstrong young socialite, volunteers to serve. She is assigned to teach children who have been rejected by the countryside to which they were evacuated. It is in this role that Mary meets Tom, an education administrator in her school district.

Their professional relationship quickly becomes personal. But when Mary meets Alistair, Tom’s best friend who has enlisted, the three are drawn into a love triangle that they must navigate while trying to survive an escalating war.

Everyone Brave is Forgiven is a sweeping epic with the same kind of unforgettable characters and scenes that made Chris Cleave’s #1 New York Times bestselling novel Little Bee a book club favorite. It is a stunning examination of what it means to love, lose and remain courageous.

Topics & Questions For Discussion

1. Both Mary and Alistair sign up to be part of the war effort almost immediately after war is declared. What are their motivations for doing so? How does each of them serve? Why is Mary surprised by her assignment?

2. When Mary first begins spending time with Tom, she describes him as “Thoughtful. Interesting. Compassionate.” (p. 41) What did you think of him? Discuss Mary’s relationship with Tom. Are the two well suited for each other? Why, or why not?

3. In a letter, Mary writes, “I was brought up to believe that everyone brave is forgiven, but in wartime courage is cheap and clemency out of season.” (p. 245) Why do you think Chris Cleave chose to take the title of his novel from this line? Does your interpretation of the title change when you read it in the full context of the quote? In what ways?

4. Mary’s student Zachary makes a big impression on her. Why? Discuss their relationship. Why does Mary write to Zachary after he has been evacuated to the countryside? How do her letters help both of them?

5. While Alistair is on leave, he returns to London and finds “there was a new way of moving that he could not seem to weave himself into.” (p. 100) Why does Alistair have difficulty adjusting to life in London? Why does Alistair put off seeing Tom? Do you think he is right in doing so? Explain your answer.

6. Early in the novel, while Mary is with Tom, she is “thinking how much she was enjoying the war.” (p. 86) Why might Mary enjoy the war? What new freedoms are afforded to her in wartime?

7. During one of her conversations with her mother, Mary notices that “There was a sadness in her mother’s eyes. Mary wondered whether it had always been there, becoming visible only now that she was attuned to sorrow’s frequency.” (p. 236) Describe Mary’s relationship with her mother. Is Mary’s mother supportive? Explain your answer. Why might Mary’s experiences during the war make her more “attuned to sorrow’s frequency”? Do these experiences help Mary better relate to her mother? Why, or why not?

8. Alistair tells Mary “Nobody is brave, the first time in an air raid.” (p. 164) How do each of the main characters react the first time that they experience an air raid? Were any of them brave? In what ways? Were you surprised by the way any of them reacted to the bombs?

9. When Mary meets with Cooper to discuss going back to work, she tells him “We needn’t put this city back the way we found it.” (p. 228) What prompts Mary to make her comment and what does she mean by it? How has life in London changed as a result of the war? Have any of those changes been positive? Why might Mary be reluctant to return to the status quo?

10. Explain the significance of Tom’s jar of blackberry jam. When Alistair is injured, he worries that “if he opened it, the dust would get into everything he minded about.” (p. 302) What does the jam represent and why doesn’t Alistair open the jar? Is Simonson right to think that “to eat the jam would be a betrayal.” (p. 393) Why? Think about your own belongings. Do you own anything like the jam jar that has special significance? Tell your book club about it.

11. Mary tells Alistair “My mother thinks [happiness] isn’t even a word, in wartime.” (p. 416) Do you think Mary’s mother is right? Why, or why not? Are there any moments of happiness in Everyone Brave is Forgiven? What are they? Discuss them with your book club.

12. What were your initial impressions of Hilda? Did they change as you learned more about her? If so, why? Discuss Hilda’s friendship with Mary. Do you think the women are good friends to each other? Explain your answer.

13. While Alistair is on leave, he, Tom, Mary and Hilda go to see Zachary’s father’s show at the Lyceum. How does each of them react to the show? Does this give you any insight into their characters? Why is Mary ashamed to go over and say hello to Zachary’s father during the interval?

14. After seeing the effects of one of the air raids, Mary “knew, now, why her father had not spoken of the last war, nor Alistair of this. It was hardly fair on the living.” (p. 268) What does Mary see that leads to her have this insight? What effect does not speaking of his experiences in war have on Alistair?

Enhance Your Book Club

1. In describing Mary, Tom tells Alistair, “She might be the only person in this city apart from you and me who understands there are many ways to serve.” (p. 32) Aside from enlisting, what other ways are there to assist in the war effort? Would you have helped in any of the ways that Mary does? Which ones appealed most to you? Why?

2. One of Mary’s first duties as a schoolmistress is to assist in evacuating the children in her class to the countryside. Learn more about the London Evacuation by visiting the Imperial War Museum’s interactive site: http://www.iwm.org.uk/history/the-evacuated-children-of-the-second-world-war. Discuss what you learn with your book club. Why might families choose to opt out of the evacuation?

3. Prior to enlisting, Alistair works as an art restorer at the Tate. On a visit back to London, he visits the museum with Mary. When they arrive “they saw that the bombing had blown its roofs off.” (p. 415) Visit the Tate’s online archive to see photos of the bomb damaged museum: http://www3.tate.org.uk/research/researchservices/archive/showcase/results.jsp?subject=266. Then, take a virtual tour of the museum’s collections to learn more about the types of art that Alistair might have restored: http://www.tate.org.uk/

4. To learn more about Chris Cleave, read reviews of Everyone Brave is Forgiven and his other bestselling books, and to connect with him online, visit his official website at http://chriscleave.com/ or join him on Twitter @chriscleave.

A Conversation With Chris Cleave

You’ve written several critically acclaimed novels, including the #1 New York Times bestseller Little Bee. Given the success of your earlier books, did you feel any added pressure when writing Everyone Brave is Forgiven? If so, how did you deal with it while you were writing?

The pressure is huge but that’s a useful problem to have. The only way I know to deal with pressure is to be more ambitious with each novel: to go deeper into the research, to reach higher with the writing and to add another layer to the psychological complexity of the characters. Sometimes I fail spectacularly, but that risk is inherent because I’m always trying to split the difference between the level I’ve reached and some platonic perfect novel. If you look at it that way, everything you’ve done so far is only a foundation, rather than an achievement in itself. This means you never step into the trap of thinking “How do I repeat those successes”? Instead you can say to yourself, with honesty: “I’m not even halfway to perfection yet—how shall I begin?”

In your author’s note you write “If you will forgive the one piece of advice a writer is qualified to give: never be afraid of showing someone you love a working draft of yourself.” (p. C) Have you learned any other lessons from writing? Can you share them with us?

I’ve learned that real life is more mysterious, frightening and fragile than anything one can make up. I’ve learned that real life doesn’t think freakish coincidences are a hackneyed plot device. Neither does real life shy away from destroying someone just because he or she is a sympathetic character.

Gloriously, I’ve also learned that people you meet in real life are very unrealistic. The marvelous problem for fiction is to capture this preposterous, implausible and blazingly eccentric life, and to put it in a cell overnight, to sober it up until it reads believably on the page. That’s what a novelist is: I’m not a creating god, I’m reality’s jailor.

Your descriptions of London during the blitz are incredibly vivid. What kind of research did you conduct to get those scenes right?

I did something louche and unfashionable: I talked with older people. I belong to the last generation of writers who can listen to elders who lived through WWII, either on the home front or as prisoners or combatants. I felt that it was important to listen to them while they were still with us to tell the tale.

Everything else, I could—and did—research in libraries and sound archives. I spent a year in dusty London basements, reading through evacuation records and logistics lists. I know how many cardboard coffins London ordered and how many it used on each night of the Blitz. I know how much an artificial leg cost to make and who produced the best ones. I even know the weights and tail fin configurations of the bombs that were most likely to cause the amputations in the first place.

In truth, I could learn far more about the war picture, both microscopic and panoramic, than anyone who lived through it could possibly have known at the time—but all of that is absolutely nothing without the life that my elderly interviewees breathed into the novel. Because what you don’t find in archives is absence: the lack of certainty about the courses of love and war, the feeling of not knowing the ending. I was—I am—in awe of the veterans I spoke with. When I look at the novel now, it seems to me that the story is mine but the fear is theirs.

In Everyone Brave is Forgiven, the action alternates between life in London during WWII and on the front. Was it difficult to change from the war front to the home front while you were writing? Can you tell us about your writing process?

While writing I thought of the novel as a tale of two sieges. Both London and Malta were effectively blockaded, and so each was a perfect pressure cooker in which my characters’ freedoms were sealed. My strategy was very simple: to respect the absolute containment of my two theatres, while obsessing about the one thin, fragile connection between them: the bridge made of letters.

What you notice when you spend several years on a project like this, and train yourself to think as your novel’s subjects thought, is what a different species they were from us. I have limited patience with people who assure us that our ancestors were “just like us.” No. By comparison, we are neurotic and fallen. We have a whimpering need to reassure ourselves that we are important and loved, through constant high-frequency, low-intensity interactions on all available channels. Our ancestors, by contrast, maintained radio silence and used rationed ink and paper. Their letters had to say more between the lines than on them.

So, my writing process was to look at a photo of my grandparents every morning before I sat down at my desk, and simply to remind myself that I was writing about people who were braver than me.

Is there anything that has been particularly rewarding about publishing Everyone Brave is Forgiven?

I’ve been glad to see the way people are using the book as a lens on how we live now. I think that’s a novelist’s job: to provide a new place for the reader to stand, from which the view back towards home is different. With my first three novels, Incendiary, Little Bee and Gold, I did this by writing characters who lived at the extremities of the contemporary experience. With Everyone Brave, I’ve gone back in time to get the same shift of perspective.

As Alistair struggles to come up with a reply to Mary, he muses that “in the history of the world there was not one example of a man ever having written a satisfactory letter to a woman who mattered to him.” (p. 247) Do you agree? Can you tell us a little about the letters that your grandfather, David, wrote to your grandmother? Did you draw any inspiration from those letters when writing Alistair’s?

I’m with Alistair on this one (although of course we could both be wrong). My grandfather’s letters to my grandmother were at their best when they were funny, and in this they were a great inspiration. I think it’s the one way in which a love letter can reduce to nothing the distance between two people: the laughter it can produce is as real and unfiltered as if the writer and the reader were sitting side by side. Everything else—an enclosed photo, a promise of intimacy, a poem (god forbid)—is only a proxy for togetherness, whereas laughter is the thing itself. I don’t know how two humorless people could ever manage to fall in love by mail. That really would be pushing the envelope.

In Everyone Brave is Forgiven, it’s clear that life on the home front is just as dangerous as life on the war front and survival cannot be taken for granted in either setting. Did you know which characters would make it through the war when you began writing?

That’s a terrific question. No, I never plan. I do a lot of research instead and then just start writing. I didn’t know which characters would survive, any more than they did. I think that was important. There are three likeable people in the book who are killed unexpectedly, and the reader might be surprised to know that for each of these I wrote the character several chapters further into the story than we see in the final version. Then I went back on an impulse and killed them, arbitrarily, in mid-sentence. This made for a lot of unexpected writing work, but that’s war: it doesn’t wait for a moment that’s convenient to the plot. In this way I created randomness and chaos that gives the novel a measure of realism, I hope.

What is your favorite moment in the book?

After poor Hilda’s face has been cut to ribbons by windshield glass, and she and Mary get high in the kitchen because they can’t deal with it any other way. Mary is busy fixing Hilda’s hair for her, and the kettle screams because the two friends can’t.

What do you like your readers to take away from Everyone Brave is Forgiven?

I admire my readers—I’ve met a great many of them now—and I would never presume to tell such people what to take away from one of my books. We bring ourselves into any story, and each of us is so different—that’s the mysterious thing about humans (and also the reason they’re worth writing about). A young person coming to Everyone Brave might not have read much about WWII yet, and so the book will be an interesting historical primer for them—certainly I’ve tried to make it accurate and readable. Someone older might have served in the war themselves, or might have close family who were involved—and in that case they’ll read the book through a more intimate lens, and the book’s images will help to surface their own memories. In any case my hope—as with all of my books—is that it will be the catalyst for some interesting discussions between readers and their friends and families. I operate on the principle that a book is small and a reader is big.

Are you working on anything now? Can you tell us about it?

I’m working all the time, but only one in four or five of my projects ever becomes a finished novel. My strongly held conviction is that there should be a prestigious literary prize for throwing away promising novels. It would be called the Phewlitzer—as in “Phew, am I glad we never had to read Chris Cleave’s novel about Noah’s wives.”

Product Details

- Publisher: S&S/Marysue Rucci Books (May 3, 2016)

- Length: 432 pages

- ISBN13: 9781501124402

Browse Related Books

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Everyone Brave is Forgiven eBook 9781501124402

- Author Photo (jpg): Chris Cleave Lou Abercrombie(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit