Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

Table of Contents

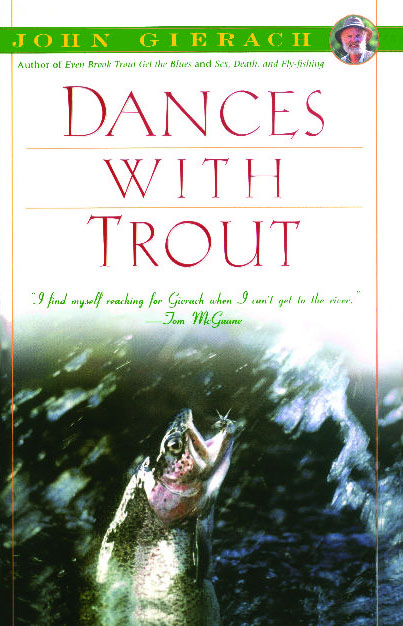

About The Book

Brilliant, witty, perceptive essays about fly-fishing, the natural world, and life in general by the acknowledged master of fishing writers.

With the wry humor and wit that have become his trademark, John Gierach writes about his travels in search of good fishing and even better fish stories. In this new collection of essays on fishing —and hunting—Gierach discusses fishing for trout in Alaska, for salmon in Scotland and for almost anything in Texas. He offers his perceptive observations on the subject of ice-fishing, getting lost, fishing at night, tournaments and the fine art of tying flies. Gierach also shares his hunting technique, which involves reading a good book and looking up occasionally to see if any deer have wandered by.

Always entertaining, often irreverent and illuminating, Gierach invites readers into his enviable way of life, and effortlessly sweeps them along. As he writes in Dances with Trout, “Fly-fishing is solitary, contemplative, misanthropic, scientific in some hands, poetic in others, and laced with conflicting aesthetic considerations. It’s not even clear if catching fish is actually the point.”

With the wry humor and wit that have become his trademark, John Gierach writes about his travels in search of good fishing and even better fish stories. In this new collection of essays on fishing —and hunting—Gierach discusses fishing for trout in Alaska, for salmon in Scotland and for almost anything in Texas. He offers his perceptive observations on the subject of ice-fishing, getting lost, fishing at night, tournaments and the fine art of tying flies. Gierach also shares his hunting technique, which involves reading a good book and looking up occasionally to see if any deer have wandered by.

Always entertaining, often irreverent and illuminating, Gierach invites readers into his enviable way of life, and effortlessly sweeps them along. As he writes in Dances with Trout, “Fly-fishing is solitary, contemplative, misanthropic, scientific in some hands, poetic in others, and laced with conflicting aesthetic considerations. It’s not even clear if catching fish is actually the point.”

Excerpt

Chapter 1

The Lake

One summer, A. K. Best, Larry Pogreba and I walked up into a high mountain valley we know of to find and fish a certain alpine lake. The most recent report we had on it was ten years old but, back then at least, it was supposed to have some big cutthroat trout. This is a remote lake that's not fished much, which naturally gets you to thinking.

I'd never been to this lake, or to any of the half dozen other lakes and hanging puddles on that far southwest ridge, even though I've been fishing, hiking and hunting in the valley off and on for somewhere between fifteen and twenty years and had, only the summer before, systematically fished the entire length of the stream from the last paved county road up to the headwaters.

I'll admit right here that this was more of a writing than a completely honest sporting proposition. I had in mind one of those gradual revelation numbers: Fishing the stream yard by yard, mile by mile, the details would build up novelistically until finally I would catch the last tiny cutthroat trout sucking snowflies from the lip of the glacier and there'd be this vague but satisfying sense of completion, which I would somehow get down on paper. I had it all worked out. Kevin Costner would play me in the movie version, Dances with Trout.

I did manage to fish the whole stream in a single season, all fifteen miles of it. If I remember right, it took ten separate trips between the end of runoff in June and the first good snow in September. Once or twice I went alone, but more often I was with A.K., Mike Price or Ed Engle.

Oddly enough, I never got close to anything especially literary or profound, except maybe at the point where I forgot why I was doing it. There was still an amorphous sense of purpose that I liked. It was more serious than play, less serious than work (a distinction made more subtle by the fact that I usually work harder playing than I do working), but in the end it became one of those things you do for the sheer hell of it, just so you can say you did it.

Also, I caught lots of fish. That's just good, clean fun but, as often as it happens, it still seems like proof of something. The trout takes the fly, the line tightens and it's like I was blind, but now I see. I have to admit there are days when I fish as a conscious act of revolution, but the days when I fish for no apparent reason at all are usually better.

I thought about keeping a journal, but when it came right down to it I didn't. For one thing, I didn't want to be bothered scribbling when I could be fishing. For another, I knew I'd be happier relying on my recollections because the memory of a fisherman is more like fiction than journalism, that is, it doesn't ignore the facts, but it's not entirely bound by them, either.

When I finally did catch what had to be the last cutthroat from the last trickle deep enough to hold one, I thought, Okay, there. Then I started thinking about that lake up on the ridge and the rumors about big trout. The lesson about writing had something to do with endings: like maybe they don't really exist in nature.

That was the summer that the idea of minimum flows lower down on the same drainage floated to the surface once again, as it does about every five years or so. By now all the studies have been done and the experts tend to agree: Water quality, biomass, species diversity -- it's all there. Just add a proper, minimum winter flow -- enough to let the larger trout live until spring -- and you'll have one hell of a trout stream.

This is something a handful of us locals have been kicking around for a couple of decades now, first as part of Trout Unlimited, then as I don't know what. At one point some people started referring to us as the TLO (the Trout Liberation Organization) but that didn't stick because right about then it was becoming clear that terrorism wasn't really very funny. I suggested the National Riffle Association, but in the end we didn't need a name because we weren't an organization in the usual sense. I think we realized it was better to remain a nameless, unorganized handful of people with a more or less common vision so that the occasional good idea wouldn't have to undergo surgery by a committee.

So for quite a while now we've been trying first one tactic and then another, keeping the idea of minimum flows alive because it might eventually catch on and looking for the chink in the state and local bureaucracies that would allow everyone in power to gracefully do the right thing.

The main problem is, it's hard to get used to the level of discourse you're involved in. When you go to a bureaucrat with an idea, he looks you in the eye, smiles warmly and thinks, "Is there anything in this for me and, if not, what's the quickest way to get rid of this guy?" When you approach a politician, he thinks, "How can I be simultaneously for and against this?" not realizing that by being on both sides of a fight he'll eventually beat himself up.

When you start talking about putting water back into a stream because it belongs there, you're screwing around with one of the oldest Old World artifacts on this continent. Water law here dates back roughly to the introduction of the horse into North America. By now it's become pretty well fossilized.

The stretch of stream I was fishing that summer was at the top end of the drainage, in a wilderness area, above the dams, ditches, headgates and all the other plumbing by which too much water was being stolen from the stream and by which also reasonable people could put some back. Not all of it -- just enough for the fish to breathe.

That upper fork is not exactly untouched, but it's still nicely out of the loop. If you walk far enough upstream, you can literally, that is, physically, leave the argument behind, and that's...what? Let's say, liberating. Or let's say that, without diminishing the importance of the environmental issue at hand, it can give you a larger perspective: Left to themselves, things are as they are because they couldn't be any other way, right?

One day, in the course of doing a lunch with a guy who might have been made to see minimum flows in the lower stream working to his advantage, the man asked me, "What is it you really want?" assuming, of course, that what I told him I wanted was a smokescreen behind which a hidden agenda was advancing unseen.

I can often wait out a trout, but I tend to lose patience quickly with humans, so I slipped and said, "What I really want is for us to disassemble enough of modern technological culture that we can become a nation of agrarian anarchist, gourmet hunter/gatherer, poet/sportsmen." That may or may not have been a mistake, but it was therapeutic.

That was also the year I began to get interested in the concept of bioregionalism: the idea that your coherent, familiar, natural habitat is much more important to you in the long run than political boundaries, not to mention much harder to define. I guess I'd known that instinctively all along, but it was only recently that I'd discovered the label and the small, backwater political movement that comes with it.

So as an exercise in visualization, I asked myself, honestly now, ignoring meaningless designations like United States of America, Colorado, Boulder County, St. Vrain Valley School District or an arbitrarily selected stretch of trout stream, where do you feel you belong? I started with the places where the water is cold enough to support trout and where I know enough to dress for the weather, overlaid the ranges of mule deer, snowshoe hares and the species of grouse I know how to hunt, added spruce, fir and pine trees and the few edible mushrooms I can identify.

It became obvious that I was fundamentally at home either in one small drainage in the Colorado Rockies or any-where in the northern third of North America. I found that helpful. Everyone should have a rough idea where home is.

The fork of the stream and the rumored cutthroat lake are in one of those classically beautiful, high, wide but somehow still intimate valleys in the Colorado Rockies, and parts of it are nicely inaccessible. First there's an hour and a half's worth of jarring, slamming bad road. Then, at the road's end, there's a pretty good uphill hike past the stretch of stream that's fished by the four-wheel brigade. After several miles the trout change from brookies to cutthroats, some of which get unusually large for that kind of high, sparse water.

The stream itself is small, cold, steep, deep in places, shallow and braided in others and jumbled with boulders and the bleached trunks of fallen spruce and fir trees. It's mostly in forest, so the water is nicely shaded, but the dense spruce and fir needles will grab your flies and leaders on careless back casts and hold on to them like Velcro.

This does not make for graceful fly-fishing. You scramble over rocks and rotting logs, make short, choppy casts and lose flies to snags but, because most fishermen won't put themselves through this -- let alone walk that far to do it -- the hardest spots give up the best trout.

This is the kind of fine little creek that grabs and holds your attention, and it's hard enough to get to in its own right that it can keep you from exploring further. But I was honestly curious about the lake, and also a little worried that someone would eventually ask me about it, based on the assumption that I've been kicking around the area for two decades and must know it like the proverbial back of my hand. I'd have to admit the truth, they'd say something like, "Oh, so in all that time you never actually went all the way back in there," and that would sting.

The three of us hiked in from the end of the four-wheel-drive road and, although we had a destination in mind, we couldn't help stopping here and there along the creek to catch, admire and release a few trout. I directed Larry to some good spots I'd discovered the year before, and in fifteen minutes he'd landed a couple of fourteen-inch cutthroats.

"Jeeze," he said, "I didn't know they got this big up here."

I beamed, proud of myself, even though he'd have found the fish easily enough without my help, and A.K. mumbled, "Just keep it to yourself, okay?"

There was talk of keeping a few trout to eat, but it was early in the day and we had a long walk ahead of us. The fish might have gotten a little funky by the time we got them home, and there are few things worse than wild trout that could have been fresh, but aren't.

Then we found the little feeder creek that was supposed to come from the lake in question and started climbing. The directions were good so far; there was the old skid road, the ruined bridge and the advice, "It's the first big feeder you come to." The slope was steep, the air was thin. A.K. and I began to plod while Larry pulled out ahead and found some perfect, doorknob-sized Boletus mushrooms that he stuffed into his fly vest.

Not far past the mushrooms we came out of the tall, shady spruce/fir forest into the open. Larry charged ahead, but A.K. and I stopped there for a few minutes to reacclimate. To me, coming out of the dark timber at high altitude is like walking out of a movie matinee into a hard, bright summer afternoon. The eyes squint, vision swims and you stoop a little so as not to bump your head on the sky.

After some more hard going we did, in fact, come to a lake, but it was too shallow, too small, obviously fishless and couldn't have been the lake.

We rested for a few minutes, then consulted the compass and map. We should have done this earlier, but the guy with the decade-old fishing report was the one who'd said to follow that particular feeder creek and we'd trusted his memory. He'd been wrong, which cast something of a shadow on the whole enterprise.

None of us are great at orienteering, but it became clear that we were too far east, although it wasn't clear how far. So we worked our way roughly west along the rock shelves, boulder fields and miniature knee- to chest-high spruce groves, finally coming to a pair of large pools on a feeder creek that weren't on the map and, a hundred feet farther up, a pair of lakes that were.

Okay, now we knew where we were. The shapes and placement of the lakes and the prominent landmarks were unmistakable. Where we needed to be was a mile or so farther south by southwest and a few hundred feet higher. We looked in that direction and there stood an enormous, ominous-looking crag of rock, on the other side of which would be the lake we wanted.

Someone dug out a watch to check the time. It was too late to do anything but fish the lakes at hand for half an hour and then head out at a quick pace if we wanted to negotiate that four-wheel-drive road with any daylight left. That seemed like a good idea, since we'd wrecked a tire on the way in and were running on the spare. We were using Larry's Suburbillac, an ingenious homemade Suburban/Cadillac/pop-up camper hybrid that I won't try to describe here. It's a solid vehicle, but too odd-looking to instill a lot of confidence in skeptical passengers.

We fished the larger of the two lakes for a while, mostly as an exercise. There were no rises, no fish cruising the shallows. In terms of vegetation, aquatic insects and trout, it looked as sterile as a stone toilet bowl. Still, after all that walking it was fun to stand and make long, straight casts out onto the pretty water.

These sparse, high lakes can and do winterkill, leaving them with no life that would interest a guy who'd carried a fly rod six or seven miles and two thousand feet up. Then again, bodies of water just like this have been known to look fishless, but hold a handful of five-pound cutthroats that you might locate after two days of watching and random casting, but not in half an hour. So if someone asks me if there are trout in Such-and-Such Lake, I'II have to answer, in all honesty, "I don't know, I didn't see any." But, I can add silently, I did go look.

We were at roughly 11,000 feet, where the air is cool, thin and dizzyingly clear, even to westerners. The larger of the two lakes was set smack against the base of a nameless (by the map) 12,400-foot peak on the Continental Divide with other sharp summits reaching past 13,000 visible along the ridge to the north and west. Looking down valley to the northeast, we could see the nearly fiat-topped, almost vertical escarpment that forms the north wall of the gorge. This is a natural barrier to the elk herds that move down and east in the fall so that, although the little valley is rich in other kinds of game, elk are rare.

Fooling around with maps of the area, I once determined that from almost any good, high vantage point in the upper valley one can see something like ninety square miles of rock, tundra, forests, lakes and trout streams. On site, it doesn't seem anywhere near that big.

The lake itself was clear at the shallow end, but the deep hole on the far side was a milky blue-green color from the little glacier to the south. Patches of the nearer snowfields had a slight pinkish cast caused by a kind of wind-borne snow mold. This stuff is said to taste like watermelon, but it's also supposed to be either a neurotoxin or a psychedelic, depending on which survivor you talk to.

This is the area that lies between timberline (above which trees won't grow tall and straight) and treeline (above which trees won't grow at all). It's called krummbolz: a German word meaning "crooked wood."

Some of the small, gnarled trees here are ancient, though how ancient I can only guess. The oldest known individual living things on the planet are some bristlecone pines living in California in terrain something like this. They're said to be well over four thousand years of age. A local botanist says that in this area krummholz spruce several hundred years old may have a trunk diameter of only four inches, and there are old trees here that are more than a foot across at the base.

It's trees like this that inspired the art of bonsai growing in China and Japan. The bonsai masterpieces (outrageous, shallowly potted trees, some of which are hundreds of years old) symbolize great strength, wiry toughness, stillness, patience, eccentricity, adaptation, harmonious balance, goofiness and the venerable wisdom that can come from old age: all the attributes enlightened humans can take from wildness if they're smart enough to pay attention.

Of course they also symbolize how an honest love of nature can turn on itself. According to bonsai grower Peter Chin, many mountainous areas of Japan were stripped of their beautiful, naturally dwarfed trees by bonsai collectors long ago. To see them now you have to go to the cities. And this from a culture that has always based its art and philosophy on a close harmony with the natural world.

It's interesting that, because we Americans have loved nature less and for a shorter time, these lovely little trees (which are, after all, too small for lumber) still grow in our mountains. In this kind of terrain you see examples of two classic bonsai styles -- kengai (cascade) and fukinagashi (windswept). Digging one to transplant would be three times harder than grunting up there to fish, and it's illegal anyway.

No trout were going to come from the lake in front of us, that much was clear, and as we were reeling in and heading back to where we'd piled our day packs, A.K. said, "It's yet another success. We said we were going fishing and that's what we did."

A thousand feet below, down in the tall, straight trees, we could see a small, nameless lake where I'd caught cutthroat trout as long as sixteen inches that year, although we wouldn't have time to fish for them now. From that vantage point we could also pick out the easy, more or less direct route to the lake we'd set out for that morning, and we filed that for future reference.

The sun was far to the west, a little over an hour from dusk. The shadows across the valley behind us were long and pointed -- olive and honey-colored on the bare rocks, almost black down in the trees and dull silver on the lower lake. The peaks on the far ridge were starting to get an amber glow. All in all, it was a far better place to be than a bar or a gas station when a flopped expedition begins to take on that aimless feeling.

It was going to be a long, fast walk out, so we broke down our rods, shouldered our packs and had that brief consultation that becomes standard with middle-aged outdoorsmen who have come to know of each other's old injuries:

"How's your back?"

"Fine, how's your foot?"

"Okay, how's your knee?"

"Sore, but it's all downhill from here."

Copyright © 1994 by John Gierach

The Lake

One summer, A. K. Best, Larry Pogreba and I walked up into a high mountain valley we know of to find and fish a certain alpine lake. The most recent report we had on it was ten years old but, back then at least, it was supposed to have some big cutthroat trout. This is a remote lake that's not fished much, which naturally gets you to thinking.

I'd never been to this lake, or to any of the half dozen other lakes and hanging puddles on that far southwest ridge, even though I've been fishing, hiking and hunting in the valley off and on for somewhere between fifteen and twenty years and had, only the summer before, systematically fished the entire length of the stream from the last paved county road up to the headwaters.

I'll admit right here that this was more of a writing than a completely honest sporting proposition. I had in mind one of those gradual revelation numbers: Fishing the stream yard by yard, mile by mile, the details would build up novelistically until finally I would catch the last tiny cutthroat trout sucking snowflies from the lip of the glacier and there'd be this vague but satisfying sense of completion, which I would somehow get down on paper. I had it all worked out. Kevin Costner would play me in the movie version, Dances with Trout.

I did manage to fish the whole stream in a single season, all fifteen miles of it. If I remember right, it took ten separate trips between the end of runoff in June and the first good snow in September. Once or twice I went alone, but more often I was with A.K., Mike Price or Ed Engle.

Oddly enough, I never got close to anything especially literary or profound, except maybe at the point where I forgot why I was doing it. There was still an amorphous sense of purpose that I liked. It was more serious than play, less serious than work (a distinction made more subtle by the fact that I usually work harder playing than I do working), but in the end it became one of those things you do for the sheer hell of it, just so you can say you did it.

Also, I caught lots of fish. That's just good, clean fun but, as often as it happens, it still seems like proof of something. The trout takes the fly, the line tightens and it's like I was blind, but now I see. I have to admit there are days when I fish as a conscious act of revolution, but the days when I fish for no apparent reason at all are usually better.

I thought about keeping a journal, but when it came right down to it I didn't. For one thing, I didn't want to be bothered scribbling when I could be fishing. For another, I knew I'd be happier relying on my recollections because the memory of a fisherman is more like fiction than journalism, that is, it doesn't ignore the facts, but it's not entirely bound by them, either.

When I finally did catch what had to be the last cutthroat from the last trickle deep enough to hold one, I thought, Okay, there. Then I started thinking about that lake up on the ridge and the rumors about big trout. The lesson about writing had something to do with endings: like maybe they don't really exist in nature.

That was the summer that the idea of minimum flows lower down on the same drainage floated to the surface once again, as it does about every five years or so. By now all the studies have been done and the experts tend to agree: Water quality, biomass, species diversity -- it's all there. Just add a proper, minimum winter flow -- enough to let the larger trout live until spring -- and you'll have one hell of a trout stream.

This is something a handful of us locals have been kicking around for a couple of decades now, first as part of Trout Unlimited, then as I don't know what. At one point some people started referring to us as the TLO (the Trout Liberation Organization) but that didn't stick because right about then it was becoming clear that terrorism wasn't really very funny. I suggested the National Riffle Association, but in the end we didn't need a name because we weren't an organization in the usual sense. I think we realized it was better to remain a nameless, unorganized handful of people with a more or less common vision so that the occasional good idea wouldn't have to undergo surgery by a committee.

So for quite a while now we've been trying first one tactic and then another, keeping the idea of minimum flows alive because it might eventually catch on and looking for the chink in the state and local bureaucracies that would allow everyone in power to gracefully do the right thing.

The main problem is, it's hard to get used to the level of discourse you're involved in. When you go to a bureaucrat with an idea, he looks you in the eye, smiles warmly and thinks, "Is there anything in this for me and, if not, what's the quickest way to get rid of this guy?" When you approach a politician, he thinks, "How can I be simultaneously for and against this?" not realizing that by being on both sides of a fight he'll eventually beat himself up.

When you start talking about putting water back into a stream because it belongs there, you're screwing around with one of the oldest Old World artifacts on this continent. Water law here dates back roughly to the introduction of the horse into North America. By now it's become pretty well fossilized.

The stretch of stream I was fishing that summer was at the top end of the drainage, in a wilderness area, above the dams, ditches, headgates and all the other plumbing by which too much water was being stolen from the stream and by which also reasonable people could put some back. Not all of it -- just enough for the fish to breathe.

That upper fork is not exactly untouched, but it's still nicely out of the loop. If you walk far enough upstream, you can literally, that is, physically, leave the argument behind, and that's...what? Let's say, liberating. Or let's say that, without diminishing the importance of the environmental issue at hand, it can give you a larger perspective: Left to themselves, things are as they are because they couldn't be any other way, right?

One day, in the course of doing a lunch with a guy who might have been made to see minimum flows in the lower stream working to his advantage, the man asked me, "What is it you really want?" assuming, of course, that what I told him I wanted was a smokescreen behind which a hidden agenda was advancing unseen.

I can often wait out a trout, but I tend to lose patience quickly with humans, so I slipped and said, "What I really want is for us to disassemble enough of modern technological culture that we can become a nation of agrarian anarchist, gourmet hunter/gatherer, poet/sportsmen." That may or may not have been a mistake, but it was therapeutic.

That was also the year I began to get interested in the concept of bioregionalism: the idea that your coherent, familiar, natural habitat is much more important to you in the long run than political boundaries, not to mention much harder to define. I guess I'd known that instinctively all along, but it was only recently that I'd discovered the label and the small, backwater political movement that comes with it.

So as an exercise in visualization, I asked myself, honestly now, ignoring meaningless designations like United States of America, Colorado, Boulder County, St. Vrain Valley School District or an arbitrarily selected stretch of trout stream, where do you feel you belong? I started with the places where the water is cold enough to support trout and where I know enough to dress for the weather, overlaid the ranges of mule deer, snowshoe hares and the species of grouse I know how to hunt, added spruce, fir and pine trees and the few edible mushrooms I can identify.

It became obvious that I was fundamentally at home either in one small drainage in the Colorado Rockies or any-where in the northern third of North America. I found that helpful. Everyone should have a rough idea where home is.

The fork of the stream and the rumored cutthroat lake are in one of those classically beautiful, high, wide but somehow still intimate valleys in the Colorado Rockies, and parts of it are nicely inaccessible. First there's an hour and a half's worth of jarring, slamming bad road. Then, at the road's end, there's a pretty good uphill hike past the stretch of stream that's fished by the four-wheel brigade. After several miles the trout change from brookies to cutthroats, some of which get unusually large for that kind of high, sparse water.

The stream itself is small, cold, steep, deep in places, shallow and braided in others and jumbled with boulders and the bleached trunks of fallen spruce and fir trees. It's mostly in forest, so the water is nicely shaded, but the dense spruce and fir needles will grab your flies and leaders on careless back casts and hold on to them like Velcro.

This does not make for graceful fly-fishing. You scramble over rocks and rotting logs, make short, choppy casts and lose flies to snags but, because most fishermen won't put themselves through this -- let alone walk that far to do it -- the hardest spots give up the best trout.

This is the kind of fine little creek that grabs and holds your attention, and it's hard enough to get to in its own right that it can keep you from exploring further. But I was honestly curious about the lake, and also a little worried that someone would eventually ask me about it, based on the assumption that I've been kicking around the area for two decades and must know it like the proverbial back of my hand. I'd have to admit the truth, they'd say something like, "Oh, so in all that time you never actually went all the way back in there," and that would sting.

The three of us hiked in from the end of the four-wheel-drive road and, although we had a destination in mind, we couldn't help stopping here and there along the creek to catch, admire and release a few trout. I directed Larry to some good spots I'd discovered the year before, and in fifteen minutes he'd landed a couple of fourteen-inch cutthroats.

"Jeeze," he said, "I didn't know they got this big up here."

I beamed, proud of myself, even though he'd have found the fish easily enough without my help, and A.K. mumbled, "Just keep it to yourself, okay?"

There was talk of keeping a few trout to eat, but it was early in the day and we had a long walk ahead of us. The fish might have gotten a little funky by the time we got them home, and there are few things worse than wild trout that could have been fresh, but aren't.

Then we found the little feeder creek that was supposed to come from the lake in question and started climbing. The directions were good so far; there was the old skid road, the ruined bridge and the advice, "It's the first big feeder you come to." The slope was steep, the air was thin. A.K. and I began to plod while Larry pulled out ahead and found some perfect, doorknob-sized Boletus mushrooms that he stuffed into his fly vest.

Not far past the mushrooms we came out of the tall, shady spruce/fir forest into the open. Larry charged ahead, but A.K. and I stopped there for a few minutes to reacclimate. To me, coming out of the dark timber at high altitude is like walking out of a movie matinee into a hard, bright summer afternoon. The eyes squint, vision swims and you stoop a little so as not to bump your head on the sky.

After some more hard going we did, in fact, come to a lake, but it was too shallow, too small, obviously fishless and couldn't have been the lake.

We rested for a few minutes, then consulted the compass and map. We should have done this earlier, but the guy with the decade-old fishing report was the one who'd said to follow that particular feeder creek and we'd trusted his memory. He'd been wrong, which cast something of a shadow on the whole enterprise.

None of us are great at orienteering, but it became clear that we were too far east, although it wasn't clear how far. So we worked our way roughly west along the rock shelves, boulder fields and miniature knee- to chest-high spruce groves, finally coming to a pair of large pools on a feeder creek that weren't on the map and, a hundred feet farther up, a pair of lakes that were.

Okay, now we knew where we were. The shapes and placement of the lakes and the prominent landmarks were unmistakable. Where we needed to be was a mile or so farther south by southwest and a few hundred feet higher. We looked in that direction and there stood an enormous, ominous-looking crag of rock, on the other side of which would be the lake we wanted.

Someone dug out a watch to check the time. It was too late to do anything but fish the lakes at hand for half an hour and then head out at a quick pace if we wanted to negotiate that four-wheel-drive road with any daylight left. That seemed like a good idea, since we'd wrecked a tire on the way in and were running on the spare. We were using Larry's Suburbillac, an ingenious homemade Suburban/Cadillac/pop-up camper hybrid that I won't try to describe here. It's a solid vehicle, but too odd-looking to instill a lot of confidence in skeptical passengers.

We fished the larger of the two lakes for a while, mostly as an exercise. There were no rises, no fish cruising the shallows. In terms of vegetation, aquatic insects and trout, it looked as sterile as a stone toilet bowl. Still, after all that walking it was fun to stand and make long, straight casts out onto the pretty water.

These sparse, high lakes can and do winterkill, leaving them with no life that would interest a guy who'd carried a fly rod six or seven miles and two thousand feet up. Then again, bodies of water just like this have been known to look fishless, but hold a handful of five-pound cutthroats that you might locate after two days of watching and random casting, but not in half an hour. So if someone asks me if there are trout in Such-and-Such Lake, I'II have to answer, in all honesty, "I don't know, I didn't see any." But, I can add silently, I did go look.

We were at roughly 11,000 feet, where the air is cool, thin and dizzyingly clear, even to westerners. The larger of the two lakes was set smack against the base of a nameless (by the map) 12,400-foot peak on the Continental Divide with other sharp summits reaching past 13,000 visible along the ridge to the north and west. Looking down valley to the northeast, we could see the nearly fiat-topped, almost vertical escarpment that forms the north wall of the gorge. This is a natural barrier to the elk herds that move down and east in the fall so that, although the little valley is rich in other kinds of game, elk are rare.

Fooling around with maps of the area, I once determined that from almost any good, high vantage point in the upper valley one can see something like ninety square miles of rock, tundra, forests, lakes and trout streams. On site, it doesn't seem anywhere near that big.

The lake itself was clear at the shallow end, but the deep hole on the far side was a milky blue-green color from the little glacier to the south. Patches of the nearer snowfields had a slight pinkish cast caused by a kind of wind-borne snow mold. This stuff is said to taste like watermelon, but it's also supposed to be either a neurotoxin or a psychedelic, depending on which survivor you talk to.

This is the area that lies between timberline (above which trees won't grow tall and straight) and treeline (above which trees won't grow at all). It's called krummbolz: a German word meaning "crooked wood."

Some of the small, gnarled trees here are ancient, though how ancient I can only guess. The oldest known individual living things on the planet are some bristlecone pines living in California in terrain something like this. They're said to be well over four thousand years of age. A local botanist says that in this area krummholz spruce several hundred years old may have a trunk diameter of only four inches, and there are old trees here that are more than a foot across at the base.

It's trees like this that inspired the art of bonsai growing in China and Japan. The bonsai masterpieces (outrageous, shallowly potted trees, some of which are hundreds of years old) symbolize great strength, wiry toughness, stillness, patience, eccentricity, adaptation, harmonious balance, goofiness and the venerable wisdom that can come from old age: all the attributes enlightened humans can take from wildness if they're smart enough to pay attention.

Of course they also symbolize how an honest love of nature can turn on itself. According to bonsai grower Peter Chin, many mountainous areas of Japan were stripped of their beautiful, naturally dwarfed trees by bonsai collectors long ago. To see them now you have to go to the cities. And this from a culture that has always based its art and philosophy on a close harmony with the natural world.

It's interesting that, because we Americans have loved nature less and for a shorter time, these lovely little trees (which are, after all, too small for lumber) still grow in our mountains. In this kind of terrain you see examples of two classic bonsai styles -- kengai (cascade) and fukinagashi (windswept). Digging one to transplant would be three times harder than grunting up there to fish, and it's illegal anyway.

No trout were going to come from the lake in front of us, that much was clear, and as we were reeling in and heading back to where we'd piled our day packs, A.K. said, "It's yet another success. We said we were going fishing and that's what we did."

A thousand feet below, down in the tall, straight trees, we could see a small, nameless lake where I'd caught cutthroat trout as long as sixteen inches that year, although we wouldn't have time to fish for them now. From that vantage point we could also pick out the easy, more or less direct route to the lake we'd set out for that morning, and we filed that for future reference.

The sun was far to the west, a little over an hour from dusk. The shadows across the valley behind us were long and pointed -- olive and honey-colored on the bare rocks, almost black down in the trees and dull silver on the lower lake. The peaks on the far ridge were starting to get an amber glow. All in all, it was a far better place to be than a bar or a gas station when a flopped expedition begins to take on that aimless feeling.

It was going to be a long, fast walk out, so we broke down our rods, shouldered our packs and had that brief consultation that becomes standard with middle-aged outdoorsmen who have come to know of each other's old injuries:

"How's your back?"

"Fine, how's your foot?"

"Okay, how's your knee?"

"Sore, but it's all downhill from here."

Copyright © 1994 by John Gierach

Product Details

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster (April 19, 1995)

- Length: 208 pages

- ISBN13: 9780671779207

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

Tom McGuane I find myself reaching for gierach when I can't get to the river.

Sports Illustrated If Mark Twain were alive and a modern-day fly-fisherman, he still would be hard put to top John Gierach in the one-liner department.

from Dances with Trout Fly-fishing is solitary, contemplative, misanthropic, scientific in some hands, poetic in others, and laced with conflicting aesthetic considerations. It's not even clear if catching fish is actually the point.

Kirkus Reviews These well-crafted gems sparkle.

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Dances With Trout Trade Paperback 9780671779207(0.1 MB)

- Author Photo (jpg): John Gierach Photograph by Michael Dvorak/@mikedflyphotography(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit