Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

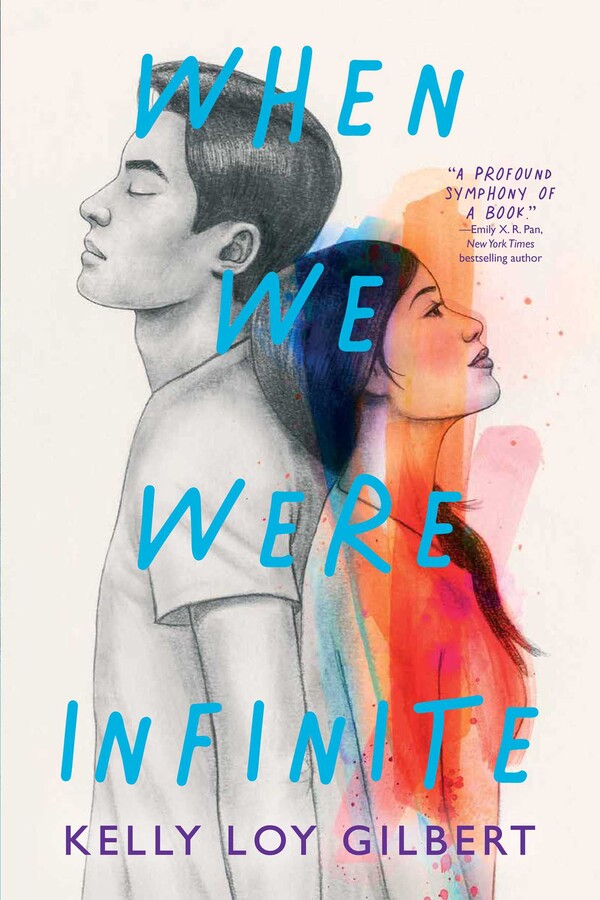

When We Were Infinite

Table of Contents

About The Book

From award-winning author Kelly Loy Gilbert comes a “beautifully, achingly cathartic” (Kirkus Reviews, starred review) romantic drama about the secrets we keep, from each other and from ourselves, perfect for fans of Permanent Record and I Am Not Your Perfect Mexican Daughter.

All Beth wants is for her tight-knit circle of friends—Grace Nakamura, Brandon Lin, Sunny Chen, and Jason Tsou—to stay together. With her family splintered and her future a question mark, these friends are all she has—even if she sometimes wonders if she truly fits in with them. Besides, she’s certain she’ll never be able to tell Jason how she really feels about him, so friendship will have to be enough.

Then Beth witnesses a private act of violence in Jason’s home, and the whole group is shaken. Beth and her friends make a pact to do whatever it takes to protect Jason, no matter the sacrifice. But when even their fierce loyalty isn’t enough to stop Jason from making a life-altering choice, Beth must decide how far she’s willing to go for him—and how much of herself she’s willing to give up.

All Beth wants is for her tight-knit circle of friends—Grace Nakamura, Brandon Lin, Sunny Chen, and Jason Tsou—to stay together. With her family splintered and her future a question mark, these friends are all she has—even if she sometimes wonders if she truly fits in with them. Besides, she’s certain she’ll never be able to tell Jason how she really feels about him, so friendship will have to be enough.

Then Beth witnesses a private act of violence in Jason’s home, and the whole group is shaken. Beth and her friends make a pact to do whatever it takes to protect Jason, no matter the sacrifice. But when even their fierce loyalty isn’t enough to stop Jason from making a life-altering choice, Beth must decide how far she’s willing to go for him—and how much of herself she’s willing to give up.

Excerpt

Chapter 1

AROUND DUSK in Congress Springs, when it’s been a clear day, the fog comes creeping over the Santa Cruz Mountains from the coast, shrouding the oaks and the redwoods in a layer of mist. The freeways there tip you north to San Francisco or south to San Jose, hugging those mountains and the foothills going up the coast on one side and the shoreline of the Bay on the other.

It was still late afternoon the day we were heading up through the Peninsula to SF for our annual Fall Showcase, and sharply clear-skied, which made it feel like the blazing gold of the oak trees and the straw-colored grass of the hills had burned away all the fog. It was October, and we were seven weeks into our school year and ten weeks into our final year in BAYS. Sometimes I wondered about early humans who watched the grasses die and the trees turn fiery and then expire, if they thought it meant their world was ending. That year, because it was our last together, it felt a little like that to me.

So far just Sunny and Jason were eighteen and could legally drive the rest of us around, so Sunny was driving; I was sitting squeezed in between Jason and Brandon in the back seat, Grace in the front, my whole world contained in that small space. Jason, Grace, and I all had our violins on our laps so Brandon’s bass would fit in the trunk with Sunny’s oboe and her stash of Costco almonds, and I was holding my phone in my hands because I was hoping to hear back from my father.

“Is that a new dress, Grace?” Sunny said as we passed the Stanford Dish. Sunny wasn’t sentimental, but when she cared about you, she followed the things in your life closely, almost osmotically. “It’s cute.”

“Thanks!” Grace said. “I thought it might work for Homecoming, too.”

“Except that Homecoming will never happen,” Brandon said, waggling his eyebrows at Sunny in the rearview mirror. “We’re all waiting for Jay’s big moment, but the end of the world will come, and there we’ll all be staring down the meteor, poor Jason waiting in his crown, and Sunny will be complaining how Homecoming still hasn’t—”

“Brandon, don’t bait her,” Grace said, at the same time Sunny said, “Okay, but seriously, I don’t understand how everyone here can have a 4.3 GPA but be so massively incompetent in basically every other area of life.” Homecoming had been repeatedly pushed back this year—now it was after Thanksgiving—because the other ASB officers had taken too long to organize everything, which Sunny had complained about both to us and to their faces for weeks, even after Austin Yim, the social manager, told her she was being kind of a bitch.

“Anyway,” Sunny said, “if Homecoming does miraculously actually happen despite the rampant incompetence, I bet Chase will ask you, Grace.”

Grace made a face. “I don’t know. He still hasn’t said anything about it.”

Grace had had a thing lately for Chase Hartley, who hung out with a somewhat porous, mostly white group of people who usually walked to the 7-Eleven at lunch and stood around the little reservoir there. Even though she and Sunny and I would spend hours afterward dissecting their hallway conversations or messages and parsing the things he said to figure out whether he was into her, I was privately hoping that he wasn’t. The last time she’d had a boyfriend—Miles Wu, for a few months when we were sophomores—she would disappear for three or four days in a row at lunch with no comment and then show up the fifth, smiling brightly, as though she hadn’t been gone at all. But then again, Grace and Jason had very briefly gone out in seventh grade before I’d known them, and so it was always a little bit of a relief when she was into someone else.

“Chase seems exactly like someone who wouldn’t think about it at all until the last possible minute,” Sunny said. “Why don’t you ask him?”

“We were all going together, right?” I said. “We could get a limo or something.”

“Maybe!” Grace said brightly. “I’ll see what happens with Chase. Or he could come with us. Brandon, you’re going, right?”

I didn’t want Chase there—I wanted just the five of us, cloistered from the rest of the world. It was only fall, still blazingly hot in the afternoons and still with the red-flag fire warnings and power blackouts in the hills to try to keep the state from incinerating, but already I’d begun to feel the pressure of the lasts—the last Fall Showcase, the last Homecoming—before the universe blew apart and scattered the five of us to who knew where.

“Are you kidding?” Brandon said. “Like I’d miss Jay’s big coronation?”

“My what?” I felt Jason turn from the window to look at us. Brandon grinned.

“Nervous about tonight?” he asked Jason. I was leaning forward to give them more room, and with Jason behind me I couldn’t see his expression, but I could imagine it—mild, guarded, the way he always looked before a performance, or a test at school.

“No,” Jason said. “You?”

We were all a little nervous, minus maybe Grace. Brandon laughed, then reached around me to smack Jason’s thigh. “Liar. And no, I’m not nervous, but I’m not the one with a solo.”

“Eh,” Jason said, “not a big solo. I’m just tired.”

I wiggled back so I was leaning against the seat too and could see them, and Jason shifted a little to let me in. “You didn’t sleep?” I said.

“I did from like twelve to two and then like four thirty to six.”

That was the worst feeling, when you couldn’t keep your eyes open any longer but you had to set your alarm for the middle of the night to wake up and finish schoolwork. I was drowning in homework and would be up late tonight too. I said, “Were you doing the Lit essay?”

“Nah, I haven’t even started. I had a bunch of SAT homework.”

“Did you guys hear Mike Low is retaking it?” Grace said, rolling her eyes. “He got a fifteen ninety, and he keeps telling everyone there was a typo.”

“He asked me to read his essay for Harvard this week,” Sunny said. “Did you guys know his older brother died in a car accident when we were little?”

“His brother?” Grace repeated. “That’s so horrible.”

“It is, but also—I don’t know, I thought it was kind of a cop-out. The essay, I mean.”

“Whoa,” Brandon said. “That’s pretty cold, Sunny. His dead brother? How is that a cop-out?”

“Not in life, obviously. That’s beyond horrible. But his essay just felt like… playing the dead brother card to get into college? I don’t know, if someone I cared about died I don’t feel like I could turn it into five hundred words for an admissions committee.”

“Gotta overcome that white legacy kid affirmative action somehow,” Brandon said. “Okay, but also, can we go back to the part where you said writing about his family tragedy is a cop-out, because—”

“Let’s help me pick a topic first,” Sunny said. “I literally have nothing like that. My essay is just going to be Hi, I love UCLA, I’ll do anything, please let me in.”

“That’s where some of your friends are, right?” Grace said.

Sunny had a group of queer friends she knew from the internet. Most of them she’d never met in real life, but one, Dayna, lived in LA and Sunny had met up with them the last time she’d gone to visit her cousins. They’d made her an elaborate, multicourse meal of Malaysian dishes and taken her to an open mic night. Sunny had been enthralled by their friends—Dayna had had to leave home after coming out to their parents, and had built their own kind of family in its place—and also radiant with joy, sending us probably a dozen video clips of the performances and pictures of the food, but when I said it sounded romantic she’d said it wasn’t, that she wasn’t Dayna’s type and they were just generous and open that way. I thought she might like them, but she always brushed it off. I followed some of her friends on social media—most of them didn’t follow me back, which was fine; they were important to me because they were important to her—and I always wondered if she ever told them she felt out of place with us, or she didn’t think we understood her.

“Just Dayna, but they’ll probably be somewhere else by then for college,” Sunny said. “It was more just—I swear sometimes Congress Springs is like so aggressively straight, or maybe that’s just high school, and I loved the whole scene there.”

She’d talked about wanting to be in LA for years now. As for me, all I wanted in life was what we had now: our Wednesday breakfasts and study sessions and hours holed up at the library or a coffee shop or each other’s homes, the performances and rehearsals together, how at any given point in the day I knew where they were and probably how they were doing. For years I had harbored a secret, desperate fantasy that we would all go together to the same college. I would give anything, I would do anything, to matter more to them than whatever unknown lives beckoned them from all those distant places.

“What are you guys writing about?” Sunny asked.

“I have nothing to write about,” Brandon said. “I’m boring. My life is boring. I would’ve thought by now I’d have, like, done something for the world.”

“That’s because you lowkey have hero syndrome,” Sunny said.

“What? I don’t have hero syndrome.”

“Okay, then would you rather date someone you didn’t like or someone who didn’t need you even a little bit?”

“Someone who didn’t need me.”

“Really? There would be nothing at all to fix in them? They wouldn’t be even the tiniest bit better off being with you?”

“She’s got a point there,” Jason said to him, amused, and Brandon flicked Sunny lightly in the shoulder. “Okay, fine, touché.”

“I kind of thought about writing about that article on moral luck,” Jason said. “I forget who posted it. Did you guys read it?” We hadn’t. “It was about how maybe whether you’re a good person or not comes down to luck. Like if you hit someone with a car and it was an accident, you aren’t guilty, just morally unlucky. Or, like—maybe you would’ve been a decent person if you grew up in, I don’t know, California today, but instead you were born during like, the Roman Empire, and so you became some bloodthirsty soldier instead.”

“Isn’t that basically the Just Following Orders excuse?” Sunny said. “Anyway, plenty of people are born in California today and aren’t decent people.”

“Right, sure,” Jason said. “I mean, you read the comments section of basically anything and you’re like, cool, half the people here are fascists. But I think the part that gets me is more the opposite. Like what if you tell yourself you’re a good person but then when it comes down to it, if you’d been born into slightly different circumstances you’d also go around crucifying people or whatever? So then you were never really good, you’ve just been morally lucky all along.”

“Nah, I think you’d hold out,” Brandon said. “You would’ve been a blacksmith or something. A doctor.”

“A Roman Empire–era doctor sounds basically as bad as a soldier,” Grace said.

“You would’ve been a soldier, definitely, Sun,” Brandon said, and Sunny laughed.

Nestled in the car there with all of them that day, I thought I’d write about them, maybe, and what they meant to me. They were the truest thing I could think to tell anyone about my life and about who I was.

My phone was still quiet when we got to the theater, and I checked my email again, just in case. Three nights ago I’d been up past two in the morning working on an email to my father. He almost always stayed up late gaming, or at least he used to, and so while I was writing I imagined him awake too, twenty miles away. Usually I didn’t invite him to things, because even if he did come, which I doubted he would, it would be unbearable if he didn’t have a good time. But this was our last Fall Showcase and my first show as the second-chair violinist, and so I’d thought—why not?

We got there at the same time as Lauren Chang and Susan Day, the third and fifth violins. When they said hi, Jason switched on a smile, what I always thought of as his public mode, and reached to hold the door open. They were midconversation, and Susan was saying, “Actually, it’s pretty impressive what you can accomplish just to trick yourself into having self-esteem,” and Jason laughed.

“That’s the most inspiring thing I’ve ever heard,” he said, and Susan blushed, pleased. When they went ahead of him inside, though, he was serious again. He caught my sleeve just before I went through the door.

“Hey,” he said quietly, “did you hear from your dad?”

I shook my head, and Jason winced. “I’m sorry.”

“It’s all right.”

“I mean—it’s not.”

It was loud when we arrived backstage, everyone spread across the risers. Jason and I took our seats at the front. Tonight’s was just a brief solo to introduce himself as the concertmaster—his more important one was later in the year—but earlier that week I’d noticed he’d bought gold rosin for his strings, something he’d always scorned as a waste of money.

“Did your parents come, Jason?” I asked, and then immediately regretted it. We all knew better than to ask about his parents.

He took a moment to answer, arranging the music on his stand. “They might’ve,” he said, politely. “I’m not really sure.”

“I’m nervous,” I said quickly, to change the subject. “Especially about the Maderna. Are you?”

“Nah, it’s so self-indulgent to be nervous.” Then he winced. “That, ah, came out wrong. I didn’t mean you.”

“No, it’s all right.”

Mr. Irving was making his way to the front of the risers, his shock of frizzy white hair tamed slightly for the occasion. Jason studied me for a moment, then offered me a smile—his real one, the corners of his eyes crinkling. “You let people get away with too much.”

When we filed onstage, it was immediately warm under the lights, and bright enough that you couldn’t make out individuals in the audience. And even though it was stupid, I let myself hope. But of course my father wasn’t out there watching. It was a weeknight, and in San Francisco, after all.

Mr. Irving held his arms up, waiting. Then he lifted them and the music began, like a thunderclap, and we were inside it.

We played our full set: a Handel, a Maderna, a Chopin. When it was time for Jason’s solo, the violins lowered our instruments. As I watched him, my heart thudded. He took a deep breath, then he straightened and drew his bow forcefully across his strings.

His style was so different from mine; I always thought of myself as slipping into a piece. Jason broke in like he was shattering glass. But then, right before the coda, I heard him start to falter—just slightly, on that run of grace notes—and I looked, alarmed, at Mr. Irving. In an orchestra, you learn to hear that point when things escape the conductor’s control, like an old cup you can fill without watching because you know the pitch change just before it overflows. I held my violin in my lap and watched Jason, willing him to stay with Mr. Irving. He held on. I smiled at him, relieved, but he was absorbed, and didn’t see me.

When we came back in, it took a beat for us to meld cleanly together again, and I couldn’t quite hear myself. Sometimes, on a piece that was especially comfortable to me, I would lift my bow slightly above my strings so that just for a few seconds my motions produced only silence, so that when I started playing again I recognized the tiny change in sound.

I was tempted to fall into that indulgence that night, to hear whatever difference I made, but I knew I couldn’t. There was, after all, an audience, and in music you could be a lot of things, but selfish wasn’t one of them.

I woke exhausted on Monday. I was desperate to sleep more, like every morning, but instead I dragged myself out of bed to shower and do my makeup and hair and brows. I could hear my mother getting ready for work, the pipes groaning when she turned on the shower. We lived in one of the older houses in Congress Springs, a dark two-story with reddish carpet and no air-conditioning, built seventy years ago back before the family diners and the feed shop and the Olan Mills studio gave way to tutoring centers and Asian markets, before white parents started holding town forums to discuss how the schools had gotten too competitive. Most adults here worked in tech, but my mother, who had gone to Lowell and then Berkeley and probably expected a brighter future, worked at a bank near downtown for what seemed like, based on how much she worried about bills, not very much money.

While I waited for my mother to be done with her shower—there’d be no hot water if I turned mine on at the same time—I checked my phone, and there was an email from doug.claire: my father. I opened it, my heart stuttering.

Sorry to miss the show, he’d written. I’ll come next time if I’m free.

You can read so much into so few words; you can conjure whole universes. And I let myself, my mind wandering, until my phone buzzed. It was Sunny, a message to me and Brandon and Grace: okay, who’s seen the review?

When I went downstairs, my mother had arranged a place setting for me: a bowl of jook carefully covered in tinfoil, a glass of milk, and a section of the newspaper, folded open. There was a note next to my bowl in her neat, small handwriting: Dear Beth, drink ALL the milk. Here is an article about your show.

Maderna’s Liriche Greche was an ambitious piece for sixty teenagers to attempt, even under the direction of celebrated veteran Joseph Irving. When the Bay Area Youth Symphony gave its anticipated Fall Showcase, the program offered a promising and impressive selection.

While the music was technically proficient—the young musicians have clearly been hard at work—at times the sound tended toward the deconstructive, occasionally to the music’s detriment. The most technically demanding section of Chopin’s Prelude 28, No. 4 was played nearly exactly as it was written on the page, with little to offer by means of interpretation or emotion. It was a surprising showing from Irving, who usually favors emotional movement over structure and rigor.

Principal violinist Jason Tsou, a senior at Las Colinas High School in Congress Springs, delivered a skillful if emotionally stunted solo. The evening’s one high point came with Tsou’s mastery of the spiccato. In Tsou’s case, perhaps the attractive glow of future potential excuses last night’s performance.

——RICH AMERY

By the time my mother dropped me off at school, Sunny, Grace, Brandon, and I had already been messaging about the review for nearly an hour. It was a cool, clear morning, mist still clinging to the foothills rising out past the track and baseball fields. The trees by the parking lot had littered layers of red and gold and orange leaves everywhere, small sunsets that crackled under your footfall.

Sunny was waiting for me by the math portables, eating her daily breakfast of almonds and dried cranberries out of a Stasher bag, which she held out to offer me. “You think Jason’s seen it yet?”

I ate an almond with exactly three cranberries so I wouldn’t mess up Sunny’s almond-to-cranberry ratio. “My guess is yes, by now. He probably went looking.”

“It wouldn’t surprise me if he was expecting it to be bad.” She glanced behind her as we started across the rally court to our lockers. “After we dropped him off last night, Brandon said last week, he and Jason were at the gym and something happened, like Jason messed up or couldn’t finish his—what do you call them? Reps?” Sunny hated the gym. “And he got mad and threw his weights across the floor. I think Brandon’s kind of worried. He said he feels like one of these days Jason’s just going to snap.”

“Snap in what way?”

“He didn’t say. And then Grace, naturally, laughed it off and told Brandon he worries too much.” Sunny rolled her eyes. “I know Grace doesn’t physically believe in things going wrong, but—”

“What are we talking about?” Grace said, smiling, materializing in front of us as we approached our lockers. Brandon was with her, drinking coffee from his Hydro Flask.

“Your relentless and extremely unfounded optimism,” Sunny said, reaching for a sip of Brandon’s coffee.

“Are you still talking about the review?” Grace said. “He said he could tell we’d been working hard, didn’t he? I think he was trying to be nice.”

“Trying to be nice? Okay, I mean, would you rather sleep through the SAT or have to tell Jason to his face that he sounded emotionally stunted?”

“Did he say anything to you about it, Brandon?” I said.

Brandon raised his eyebrows. “What about any of your interactions with Jason makes you think he would see it and, what, call me? Text me emojis about it?”

“It’s better than if he just doesn’t talk about it with anyone.”

He laughed at me. “You really didn’t grow up in a real Asian home, huh? Gotta work on that repression.”

“Brandon,” Grace scolded. She knew about that twinge in my chest I always got whenever someone commented how Asian I wasn’t. It marked my lack of wholeness, how visibly I never quite belonged. My mother had grown up in the Sunset District in San Francisco, the daughter of parents who’d run a laundry service and preferred not to talk about their difficult pasts, and she spoke Cantonese but had never taught me or sent me to Chinese school. She’d married a white man—my father was a fourth-generation Idahoan before he moved here—and our last name was Claire. Sunny and Brandon and Jason’s families were all from Taiwan—Sunny and Brandon were both born there—and sometimes it seemed like everyone but me knew the same places to eat in the night markets in Taipei, the same apps you used for group chats with your cousins overseas. Grace’s family had been here for four generations, and every year her huge extended family went on cruises together and all wore matching jerseys with NAKAMURA on the back. My mother was an only child and the daughter of only children, and so I didn’t belong to any family in that same way in any country. I belonged, instead, to my friends.

“So you think Jason’s upset?” I said.

“I think it’s going to really fuck him up,” Brandon said.

“Do you think there’s any chance at all he’ll think it wasn’t that bad?”

Brandon snorted. “None.”

We found Jason by the poster wall outside the cafeteria with Katie Perez, the senior class president. They were hanging a sign among all the others advertising service club activities: a used graphing calculator drive, a gun violence walkout, a climate change march. He looked pleasant and nonchalant, although he always did in front of other people. Sometimes when I saw him, the angular lines of his face that were always both familiar and elusive to me, something inside me went off like a camera flash.

“DIY pumpkin porg making, huh?” Brandon said, reading Katie’s poster.

Grace squinted. “What’s porg? Is that like a health food?”

“From Star Wars,” Katie said. “That was the fundraiser we all voted on, remember?”

Jason laughed, handing back her masking tape. “The representation the people demand.”

“Yes, the people don’t realize how much work it’s going to be to get a million, like, pumpkins and googly eyes,” Katie said. “Okay, I’m off to copy more flyers. Thanks, Jason.”

And then it was just us. I knew Brandon was probably right, but if Jason brought up the review, it would mean it was okay. We could pick it apart and strip it of its power; we could drown it out with all our voices instead.

We waited to see what Jason would say, trying to pretend we weren’t.

“I’ll be honest,” he said. “Porgs are the only part of Star Wars I would expect you to know about, Grace.” So he wouldn’t say anything, then, which meant neither would we.

AROUND DUSK in Congress Springs, when it’s been a clear day, the fog comes creeping over the Santa Cruz Mountains from the coast, shrouding the oaks and the redwoods in a layer of mist. The freeways there tip you north to San Francisco or south to San Jose, hugging those mountains and the foothills going up the coast on one side and the shoreline of the Bay on the other.

It was still late afternoon the day we were heading up through the Peninsula to SF for our annual Fall Showcase, and sharply clear-skied, which made it feel like the blazing gold of the oak trees and the straw-colored grass of the hills had burned away all the fog. It was October, and we were seven weeks into our school year and ten weeks into our final year in BAYS. Sometimes I wondered about early humans who watched the grasses die and the trees turn fiery and then expire, if they thought it meant their world was ending. That year, because it was our last together, it felt a little like that to me.

So far just Sunny and Jason were eighteen and could legally drive the rest of us around, so Sunny was driving; I was sitting squeezed in between Jason and Brandon in the back seat, Grace in the front, my whole world contained in that small space. Jason, Grace, and I all had our violins on our laps so Brandon’s bass would fit in the trunk with Sunny’s oboe and her stash of Costco almonds, and I was holding my phone in my hands because I was hoping to hear back from my father.

“Is that a new dress, Grace?” Sunny said as we passed the Stanford Dish. Sunny wasn’t sentimental, but when she cared about you, she followed the things in your life closely, almost osmotically. “It’s cute.”

“Thanks!” Grace said. “I thought it might work for Homecoming, too.”

“Except that Homecoming will never happen,” Brandon said, waggling his eyebrows at Sunny in the rearview mirror. “We’re all waiting for Jay’s big moment, but the end of the world will come, and there we’ll all be staring down the meteor, poor Jason waiting in his crown, and Sunny will be complaining how Homecoming still hasn’t—”

“Brandon, don’t bait her,” Grace said, at the same time Sunny said, “Okay, but seriously, I don’t understand how everyone here can have a 4.3 GPA but be so massively incompetent in basically every other area of life.” Homecoming had been repeatedly pushed back this year—now it was after Thanksgiving—because the other ASB officers had taken too long to organize everything, which Sunny had complained about both to us and to their faces for weeks, even after Austin Yim, the social manager, told her she was being kind of a bitch.

“Anyway,” Sunny said, “if Homecoming does miraculously actually happen despite the rampant incompetence, I bet Chase will ask you, Grace.”

Grace made a face. “I don’t know. He still hasn’t said anything about it.”

Grace had had a thing lately for Chase Hartley, who hung out with a somewhat porous, mostly white group of people who usually walked to the 7-Eleven at lunch and stood around the little reservoir there. Even though she and Sunny and I would spend hours afterward dissecting their hallway conversations or messages and parsing the things he said to figure out whether he was into her, I was privately hoping that he wasn’t. The last time she’d had a boyfriend—Miles Wu, for a few months when we were sophomores—she would disappear for three or four days in a row at lunch with no comment and then show up the fifth, smiling brightly, as though she hadn’t been gone at all. But then again, Grace and Jason had very briefly gone out in seventh grade before I’d known them, and so it was always a little bit of a relief when she was into someone else.

“Chase seems exactly like someone who wouldn’t think about it at all until the last possible minute,” Sunny said. “Why don’t you ask him?”

“We were all going together, right?” I said. “We could get a limo or something.”

“Maybe!” Grace said brightly. “I’ll see what happens with Chase. Or he could come with us. Brandon, you’re going, right?”

I didn’t want Chase there—I wanted just the five of us, cloistered from the rest of the world. It was only fall, still blazingly hot in the afternoons and still with the red-flag fire warnings and power blackouts in the hills to try to keep the state from incinerating, but already I’d begun to feel the pressure of the lasts—the last Fall Showcase, the last Homecoming—before the universe blew apart and scattered the five of us to who knew where.

“Are you kidding?” Brandon said. “Like I’d miss Jay’s big coronation?”

“My what?” I felt Jason turn from the window to look at us. Brandon grinned.

“Nervous about tonight?” he asked Jason. I was leaning forward to give them more room, and with Jason behind me I couldn’t see his expression, but I could imagine it—mild, guarded, the way he always looked before a performance, or a test at school.

“No,” Jason said. “You?”

We were all a little nervous, minus maybe Grace. Brandon laughed, then reached around me to smack Jason’s thigh. “Liar. And no, I’m not nervous, but I’m not the one with a solo.”

“Eh,” Jason said, “not a big solo. I’m just tired.”

I wiggled back so I was leaning against the seat too and could see them, and Jason shifted a little to let me in. “You didn’t sleep?” I said.

“I did from like twelve to two and then like four thirty to six.”

That was the worst feeling, when you couldn’t keep your eyes open any longer but you had to set your alarm for the middle of the night to wake up and finish schoolwork. I was drowning in homework and would be up late tonight too. I said, “Were you doing the Lit essay?”

“Nah, I haven’t even started. I had a bunch of SAT homework.”

“Did you guys hear Mike Low is retaking it?” Grace said, rolling her eyes. “He got a fifteen ninety, and he keeps telling everyone there was a typo.”

“He asked me to read his essay for Harvard this week,” Sunny said. “Did you guys know his older brother died in a car accident when we were little?”

“His brother?” Grace repeated. “That’s so horrible.”

“It is, but also—I don’t know, I thought it was kind of a cop-out. The essay, I mean.”

“Whoa,” Brandon said. “That’s pretty cold, Sunny. His dead brother? How is that a cop-out?”

“Not in life, obviously. That’s beyond horrible. But his essay just felt like… playing the dead brother card to get into college? I don’t know, if someone I cared about died I don’t feel like I could turn it into five hundred words for an admissions committee.”

“Gotta overcome that white legacy kid affirmative action somehow,” Brandon said. “Okay, but also, can we go back to the part where you said writing about his family tragedy is a cop-out, because—”

“Let’s help me pick a topic first,” Sunny said. “I literally have nothing like that. My essay is just going to be Hi, I love UCLA, I’ll do anything, please let me in.”

“That’s where some of your friends are, right?” Grace said.

Sunny had a group of queer friends she knew from the internet. Most of them she’d never met in real life, but one, Dayna, lived in LA and Sunny had met up with them the last time she’d gone to visit her cousins. They’d made her an elaborate, multicourse meal of Malaysian dishes and taken her to an open mic night. Sunny had been enthralled by their friends—Dayna had had to leave home after coming out to their parents, and had built their own kind of family in its place—and also radiant with joy, sending us probably a dozen video clips of the performances and pictures of the food, but when I said it sounded romantic she’d said it wasn’t, that she wasn’t Dayna’s type and they were just generous and open that way. I thought she might like them, but she always brushed it off. I followed some of her friends on social media—most of them didn’t follow me back, which was fine; they were important to me because they were important to her—and I always wondered if she ever told them she felt out of place with us, or she didn’t think we understood her.

“Just Dayna, but they’ll probably be somewhere else by then for college,” Sunny said. “It was more just—I swear sometimes Congress Springs is like so aggressively straight, or maybe that’s just high school, and I loved the whole scene there.”

She’d talked about wanting to be in LA for years now. As for me, all I wanted in life was what we had now: our Wednesday breakfasts and study sessions and hours holed up at the library or a coffee shop or each other’s homes, the performances and rehearsals together, how at any given point in the day I knew where they were and probably how they were doing. For years I had harbored a secret, desperate fantasy that we would all go together to the same college. I would give anything, I would do anything, to matter more to them than whatever unknown lives beckoned them from all those distant places.

“What are you guys writing about?” Sunny asked.

“I have nothing to write about,” Brandon said. “I’m boring. My life is boring. I would’ve thought by now I’d have, like, done something for the world.”

“That’s because you lowkey have hero syndrome,” Sunny said.

“What? I don’t have hero syndrome.”

“Okay, then would you rather date someone you didn’t like or someone who didn’t need you even a little bit?”

“Someone who didn’t need me.”

“Really? There would be nothing at all to fix in them? They wouldn’t be even the tiniest bit better off being with you?”

“She’s got a point there,” Jason said to him, amused, and Brandon flicked Sunny lightly in the shoulder. “Okay, fine, touché.”

“I kind of thought about writing about that article on moral luck,” Jason said. “I forget who posted it. Did you guys read it?” We hadn’t. “It was about how maybe whether you’re a good person or not comes down to luck. Like if you hit someone with a car and it was an accident, you aren’t guilty, just morally unlucky. Or, like—maybe you would’ve been a decent person if you grew up in, I don’t know, California today, but instead you were born during like, the Roman Empire, and so you became some bloodthirsty soldier instead.”

“Isn’t that basically the Just Following Orders excuse?” Sunny said. “Anyway, plenty of people are born in California today and aren’t decent people.”

“Right, sure,” Jason said. “I mean, you read the comments section of basically anything and you’re like, cool, half the people here are fascists. But I think the part that gets me is more the opposite. Like what if you tell yourself you’re a good person but then when it comes down to it, if you’d been born into slightly different circumstances you’d also go around crucifying people or whatever? So then you were never really good, you’ve just been morally lucky all along.”

“Nah, I think you’d hold out,” Brandon said. “You would’ve been a blacksmith or something. A doctor.”

“A Roman Empire–era doctor sounds basically as bad as a soldier,” Grace said.

“You would’ve been a soldier, definitely, Sun,” Brandon said, and Sunny laughed.

Nestled in the car there with all of them that day, I thought I’d write about them, maybe, and what they meant to me. They were the truest thing I could think to tell anyone about my life and about who I was.

My phone was still quiet when we got to the theater, and I checked my email again, just in case. Three nights ago I’d been up past two in the morning working on an email to my father. He almost always stayed up late gaming, or at least he used to, and so while I was writing I imagined him awake too, twenty miles away. Usually I didn’t invite him to things, because even if he did come, which I doubted he would, it would be unbearable if he didn’t have a good time. But this was our last Fall Showcase and my first show as the second-chair violinist, and so I’d thought—why not?

We got there at the same time as Lauren Chang and Susan Day, the third and fifth violins. When they said hi, Jason switched on a smile, what I always thought of as his public mode, and reached to hold the door open. They were midconversation, and Susan was saying, “Actually, it’s pretty impressive what you can accomplish just to trick yourself into having self-esteem,” and Jason laughed.

“That’s the most inspiring thing I’ve ever heard,” he said, and Susan blushed, pleased. When they went ahead of him inside, though, he was serious again. He caught my sleeve just before I went through the door.

“Hey,” he said quietly, “did you hear from your dad?”

I shook my head, and Jason winced. “I’m sorry.”

“It’s all right.”

“I mean—it’s not.”

It was loud when we arrived backstage, everyone spread across the risers. Jason and I took our seats at the front. Tonight’s was just a brief solo to introduce himself as the concertmaster—his more important one was later in the year—but earlier that week I’d noticed he’d bought gold rosin for his strings, something he’d always scorned as a waste of money.

“Did your parents come, Jason?” I asked, and then immediately regretted it. We all knew better than to ask about his parents.

He took a moment to answer, arranging the music on his stand. “They might’ve,” he said, politely. “I’m not really sure.”

“I’m nervous,” I said quickly, to change the subject. “Especially about the Maderna. Are you?”

“Nah, it’s so self-indulgent to be nervous.” Then he winced. “That, ah, came out wrong. I didn’t mean you.”

“No, it’s all right.”

Mr. Irving was making his way to the front of the risers, his shock of frizzy white hair tamed slightly for the occasion. Jason studied me for a moment, then offered me a smile—his real one, the corners of his eyes crinkling. “You let people get away with too much.”

When we filed onstage, it was immediately warm under the lights, and bright enough that you couldn’t make out individuals in the audience. And even though it was stupid, I let myself hope. But of course my father wasn’t out there watching. It was a weeknight, and in San Francisco, after all.

Mr. Irving held his arms up, waiting. Then he lifted them and the music began, like a thunderclap, and we were inside it.

We played our full set: a Handel, a Maderna, a Chopin. When it was time for Jason’s solo, the violins lowered our instruments. As I watched him, my heart thudded. He took a deep breath, then he straightened and drew his bow forcefully across his strings.

His style was so different from mine; I always thought of myself as slipping into a piece. Jason broke in like he was shattering glass. But then, right before the coda, I heard him start to falter—just slightly, on that run of grace notes—and I looked, alarmed, at Mr. Irving. In an orchestra, you learn to hear that point when things escape the conductor’s control, like an old cup you can fill without watching because you know the pitch change just before it overflows. I held my violin in my lap and watched Jason, willing him to stay with Mr. Irving. He held on. I smiled at him, relieved, but he was absorbed, and didn’t see me.

When we came back in, it took a beat for us to meld cleanly together again, and I couldn’t quite hear myself. Sometimes, on a piece that was especially comfortable to me, I would lift my bow slightly above my strings so that just for a few seconds my motions produced only silence, so that when I started playing again I recognized the tiny change in sound.

I was tempted to fall into that indulgence that night, to hear whatever difference I made, but I knew I couldn’t. There was, after all, an audience, and in music you could be a lot of things, but selfish wasn’t one of them.

I woke exhausted on Monday. I was desperate to sleep more, like every morning, but instead I dragged myself out of bed to shower and do my makeup and hair and brows. I could hear my mother getting ready for work, the pipes groaning when she turned on the shower. We lived in one of the older houses in Congress Springs, a dark two-story with reddish carpet and no air-conditioning, built seventy years ago back before the family diners and the feed shop and the Olan Mills studio gave way to tutoring centers and Asian markets, before white parents started holding town forums to discuss how the schools had gotten too competitive. Most adults here worked in tech, but my mother, who had gone to Lowell and then Berkeley and probably expected a brighter future, worked at a bank near downtown for what seemed like, based on how much she worried about bills, not very much money.

While I waited for my mother to be done with her shower—there’d be no hot water if I turned mine on at the same time—I checked my phone, and there was an email from doug.claire: my father. I opened it, my heart stuttering.

Sorry to miss the show, he’d written. I’ll come next time if I’m free.

You can read so much into so few words; you can conjure whole universes. And I let myself, my mind wandering, until my phone buzzed. It was Sunny, a message to me and Brandon and Grace: okay, who’s seen the review?

When I went downstairs, my mother had arranged a place setting for me: a bowl of jook carefully covered in tinfoil, a glass of milk, and a section of the newspaper, folded open. There was a note next to my bowl in her neat, small handwriting: Dear Beth, drink ALL the milk. Here is an article about your show.

Maderna’s Liriche Greche was an ambitious piece for sixty teenagers to attempt, even under the direction of celebrated veteran Joseph Irving. When the Bay Area Youth Symphony gave its anticipated Fall Showcase, the program offered a promising and impressive selection.

While the music was technically proficient—the young musicians have clearly been hard at work—at times the sound tended toward the deconstructive, occasionally to the music’s detriment. The most technically demanding section of Chopin’s Prelude 28, No. 4 was played nearly exactly as it was written on the page, with little to offer by means of interpretation or emotion. It was a surprising showing from Irving, who usually favors emotional movement over structure and rigor.

Principal violinist Jason Tsou, a senior at Las Colinas High School in Congress Springs, delivered a skillful if emotionally stunted solo. The evening’s one high point came with Tsou’s mastery of the spiccato. In Tsou’s case, perhaps the attractive glow of future potential excuses last night’s performance.

——RICH AMERY

By the time my mother dropped me off at school, Sunny, Grace, Brandon, and I had already been messaging about the review for nearly an hour. It was a cool, clear morning, mist still clinging to the foothills rising out past the track and baseball fields. The trees by the parking lot had littered layers of red and gold and orange leaves everywhere, small sunsets that crackled under your footfall.

Sunny was waiting for me by the math portables, eating her daily breakfast of almonds and dried cranberries out of a Stasher bag, which she held out to offer me. “You think Jason’s seen it yet?”

I ate an almond with exactly three cranberries so I wouldn’t mess up Sunny’s almond-to-cranberry ratio. “My guess is yes, by now. He probably went looking.”

“It wouldn’t surprise me if he was expecting it to be bad.” She glanced behind her as we started across the rally court to our lockers. “After we dropped him off last night, Brandon said last week, he and Jason were at the gym and something happened, like Jason messed up or couldn’t finish his—what do you call them? Reps?” Sunny hated the gym. “And he got mad and threw his weights across the floor. I think Brandon’s kind of worried. He said he feels like one of these days Jason’s just going to snap.”

“Snap in what way?”

“He didn’t say. And then Grace, naturally, laughed it off and told Brandon he worries too much.” Sunny rolled her eyes. “I know Grace doesn’t physically believe in things going wrong, but—”

“What are we talking about?” Grace said, smiling, materializing in front of us as we approached our lockers. Brandon was with her, drinking coffee from his Hydro Flask.

“Your relentless and extremely unfounded optimism,” Sunny said, reaching for a sip of Brandon’s coffee.

“Are you still talking about the review?” Grace said. “He said he could tell we’d been working hard, didn’t he? I think he was trying to be nice.”

“Trying to be nice? Okay, I mean, would you rather sleep through the SAT or have to tell Jason to his face that he sounded emotionally stunted?”

“Did he say anything to you about it, Brandon?” I said.

Brandon raised his eyebrows. “What about any of your interactions with Jason makes you think he would see it and, what, call me? Text me emojis about it?”

“It’s better than if he just doesn’t talk about it with anyone.”

He laughed at me. “You really didn’t grow up in a real Asian home, huh? Gotta work on that repression.”

“Brandon,” Grace scolded. She knew about that twinge in my chest I always got whenever someone commented how Asian I wasn’t. It marked my lack of wholeness, how visibly I never quite belonged. My mother had grown up in the Sunset District in San Francisco, the daughter of parents who’d run a laundry service and preferred not to talk about their difficult pasts, and she spoke Cantonese but had never taught me or sent me to Chinese school. She’d married a white man—my father was a fourth-generation Idahoan before he moved here—and our last name was Claire. Sunny and Brandon and Jason’s families were all from Taiwan—Sunny and Brandon were both born there—and sometimes it seemed like everyone but me knew the same places to eat in the night markets in Taipei, the same apps you used for group chats with your cousins overseas. Grace’s family had been here for four generations, and every year her huge extended family went on cruises together and all wore matching jerseys with NAKAMURA on the back. My mother was an only child and the daughter of only children, and so I didn’t belong to any family in that same way in any country. I belonged, instead, to my friends.

“So you think Jason’s upset?” I said.

“I think it’s going to really fuck him up,” Brandon said.

“Do you think there’s any chance at all he’ll think it wasn’t that bad?”

Brandon snorted. “None.”

We found Jason by the poster wall outside the cafeteria with Katie Perez, the senior class president. They were hanging a sign among all the others advertising service club activities: a used graphing calculator drive, a gun violence walkout, a climate change march. He looked pleasant and nonchalant, although he always did in front of other people. Sometimes when I saw him, the angular lines of his face that were always both familiar and elusive to me, something inside me went off like a camera flash.

“DIY pumpkin porg making, huh?” Brandon said, reading Katie’s poster.

Grace squinted. “What’s porg? Is that like a health food?”

“From Star Wars,” Katie said. “That was the fundraiser we all voted on, remember?”

Jason laughed, handing back her masking tape. “The representation the people demand.”

“Yes, the people don’t realize how much work it’s going to be to get a million, like, pumpkins and googly eyes,” Katie said. “Okay, I’m off to copy more flyers. Thanks, Jason.”

And then it was just us. I knew Brandon was probably right, but if Jason brought up the review, it would mean it was okay. We could pick it apart and strip it of its power; we could drown it out with all our voices instead.

We waited to see what Jason would say, trying to pretend we weren’t.

“I’ll be honest,” he said. “Porgs are the only part of Star Wars I would expect you to know about, Grace.” So he wouldn’t say anything, then, which meant neither would we.

Product Details

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers (April 19, 2022)

- Length: 384 pages

- ISBN13: 9781534468221

- Grades: 7 and up

- Ages: 12 - 99

- Lexile ® 910L The Lexile reading levels have been certified by the Lexile developer, MetaMetrics®

Browse Related Books

Awards and Honors

- Bank Street Best Children's Book of the Year Selection Title

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): When We Were Infinite Trade Paperback 9781534468221