Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

Table of Contents

About The Book

“Paul is dead.”

It was the late 1960s, the Beatles hadn’t toured since 1966, and some truly bizarre indications began appearing, pointing to the unthinkable: Paul McCartney had been killed in a car accident and replaced by a look-alike. The Walrus Was Paul unearths every single clue from one of rock ’n’ roll’s most enduring puzzles and takes you on a magical mystery tour of baffling, yet fascinating, hints for solving this mystery.

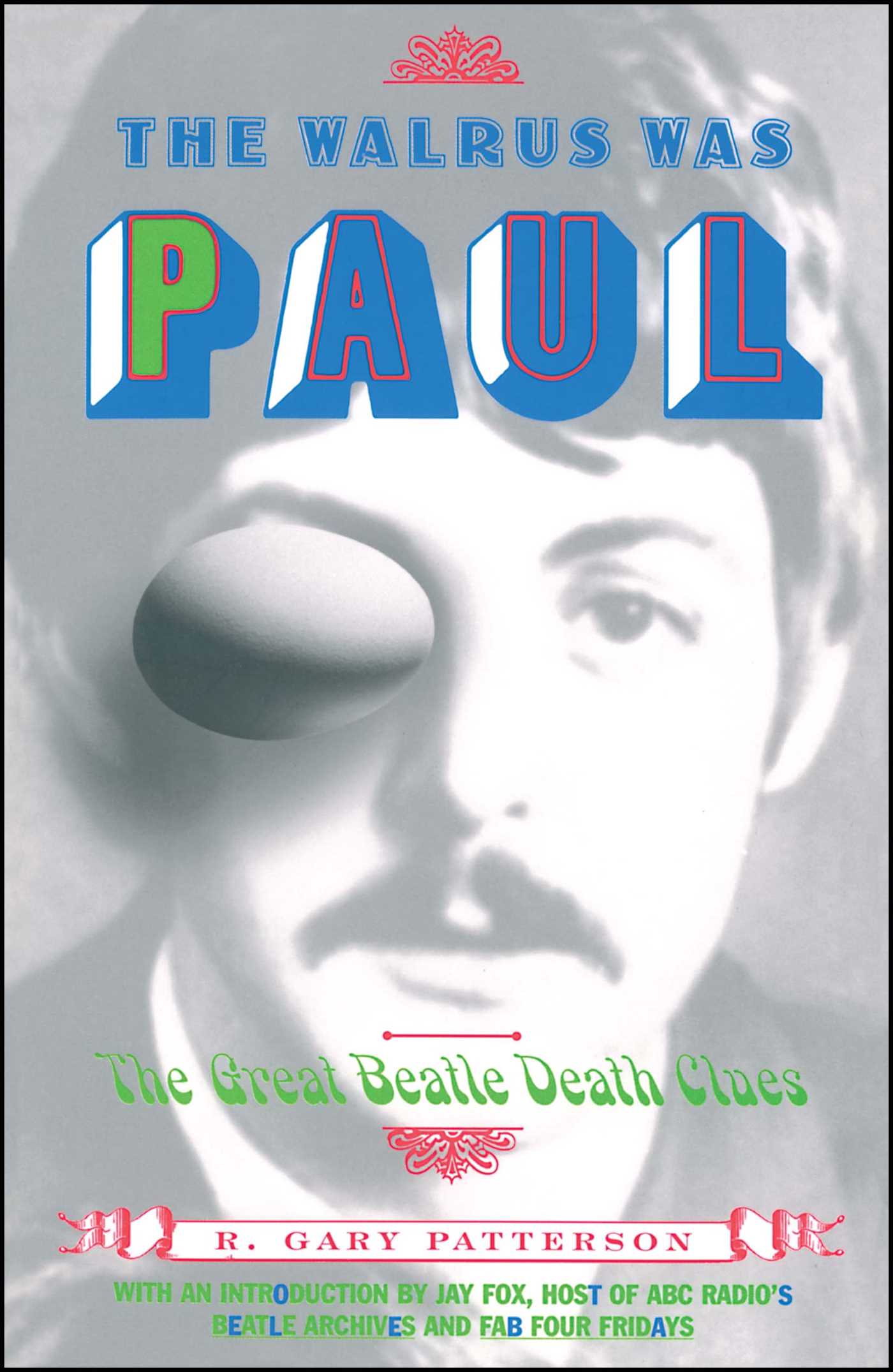

Test your “Paul is dead” trivia knowledge. Did you find and answer the following clues on the front cover?

To what song does the title, The Walrus Was Paul, refer?

-“I Am the Walrus,” which appeared on the clue-filled album Magical Mystery Tour.

There is an egg in Paul’s eye. Why?

-In the song “I Am the Walrus,” John Lennon sings, “I am the eggman...I am the walrus”—and later, in the song “Glass Onion,” we find out that, in fact, “the walrus was Paul.”

To what album (and richest source of “Paul is dead” clues) do the red, Victorian-style design elements on the front refer?

-Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band

Why is the image of Paul McCartney on the cover blurry? Are there distinguishing characteristics that might lead you to conclude something is awry?

-Many photographs of Paul in these questionable years were blurry, and Paul had a mustache, which allegedly concealed the fact that this was not Paul and the plastic-surgery scars were being hidden from his curious public.

The anagram on the bottom of the cover refers to a Greek island where John Lennon had what planned?

-The island Leso is the “hidden Greek island” on which John Lennon planned to bury Paul, and it is spelled out as “Be at Leso” on the cover of Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band.

It was the late 1960s, the Beatles hadn’t toured since 1966, and some truly bizarre indications began appearing, pointing to the unthinkable: Paul McCartney had been killed in a car accident and replaced by a look-alike. The Walrus Was Paul unearths every single clue from one of rock ’n’ roll’s most enduring puzzles and takes you on a magical mystery tour of baffling, yet fascinating, hints for solving this mystery.

Test your “Paul is dead” trivia knowledge. Did you find and answer the following clues on the front cover?

To what song does the title, The Walrus Was Paul, refer?

-“I Am the Walrus,” which appeared on the clue-filled album Magical Mystery Tour.

There is an egg in Paul’s eye. Why?

-In the song “I Am the Walrus,” John Lennon sings, “I am the eggman...I am the walrus”—and later, in the song “Glass Onion,” we find out that, in fact, “the walrus was Paul.”

To what album (and richest source of “Paul is dead” clues) do the red, Victorian-style design elements on the front refer?

-Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band

Why is the image of Paul McCartney on the cover blurry? Are there distinguishing characteristics that might lead you to conclude something is awry?

-Many photographs of Paul in these questionable years were blurry, and Paul had a mustache, which allegedly concealed the fact that this was not Paul and the plastic-surgery scars were being hidden from his curious public.

The anagram on the bottom of the cover refers to a Greek island where John Lennon had what planned?

-The island Leso is the “hidden Greek island” on which John Lennon planned to bury Paul, and it is spelled out as “Be at Leso” on the cover of Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band.

Excerpt

Chapter One: I Buried Paul

THE BRITISH INVASION AND THE AMERICAN MASS MEDIA

The Beatles were the musical messiahs of the turbulent sixties. John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison, and Ringo Starr led the British invasion that overran America's youth. No other British force, from Henry Clinton and George Cornwallis to Sir Edward Pakenham, accomplished so convincing a victory upon American soil. The method of conquest was not with fire and sword, but with electric guitars, amplifiers, and fab songs that infected every American household with the Mersey Beat.

American television, that unsuspecting British ally, innocently brought the Beatles into our living rooms on February 9, 1964, mainly due to the foresight of Ed Sullivan. But not even Sullivan, the promoter who introduced the American public to the likes of Robert Goulet and Elvis, foresaw the tidal wave that was about to hit American shores.

On that peaceful winter night, the home-viewing audience was said to have numbered well over seventy-three million Americans. Although a veteran of the television wars, Ed Sullivan must have been amazed that this British group was such a huge draw. Elvis Presley had set the record for the highest number of studio tickets requested: over seven thousand for his appearance in 1958. In what was a foreshadowing of things to come, the show had received over sixty thousand requests for tickets to the Beatle performance. Though some sources maintain that the television studio's seating capacity was only seven hundred, eight hundred tickets were given out through an impartial drawing, and those breathless individuals, chosen by fate, became live witnesses to the surrender of American youth.

The Beatles' form of rock and roll blazed like wildfire through record stores and television dance shows (American Bandstand; Ready, Steady, Go!; Hullabaloo; and Shindig). A new culture and art form, one that America sorely needed, was born.

The Beatles' moptop haircuts, Nehru jackets, and Cuban-heeled boots, not to mention their tight harmonies and melodies, helped combat the grief of a country still reeling from the untimely assassination of John F. Kennedy -- the president who, more than any other, symbolized an era of youth, hope, and opportunity.

Unfortunately, rock and roll proved to be just as susceptible to the same tragedies that seemed to infuse so many other aspects of American life during the sixties. On February 3, 1959, just a few miles outside Clear Lake, Iowa, Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and the Big Bopper perished in a fiery plane crash. The next year, Eddie Cochran died of injuries received in an automobile accident on April 17, 1960. Holly, Valens, the Big Bopper, and Cochran had all died tragically at the very height of their fame. On October 12, 1969 radio call-in lines across the country were backlogged with urgent requests from hysterical fans who demanded an answer to the same question: Had Beatle Paul McCartney died, too?

On October 12, 1969, Russ Gibb, disk jockey for Detroit's underground station WKNR-FM, received the phone call that would launch an unprecedented outbreak of hysteria throughout the pop world. The caller, who gave his name only as Tom, suggested that Gibb listen carefully to the fadeouts of certain Beatle songs. The Beatles' Abbey Road had just been released, but this early investigation concentrated on "Revolution 9" from The Beatles (the White Album) as well as the muffled murmuring at the conclusion of "Strawberry Fields Forever." As Gibb listened intently, he heard what seemed to be a number of references that seemed to suggest that Paul McCartney had met with an untimely end.

Many claim that one of the first written reports of the "Paul is dead" rumor was an article written by Tim Harper that appeared in a college newspaper in Des Moines, Iowa, on September 17, 1969. The article, "Is Paul Dead?" also appeared in the Chicago Sun-Times on October 21, 1969. WABC-AM (New York City) DJ Robey Younge also remembered receiving mysterious calls from some of his listeners begging him to help get the tragic story to the outside world. WABC-AM was a powerful station, especially at night, and could sometimes reach forty states with its broadcast signal. In an exclusive interview with my friend Joe Johnson for his syndicated Beatle Brunch radio program, Younge recounted his role in the McCartney mystery. "'Paul McCartney dead' is something I did one strange night after some kids had called me up from the Midwest, 'cause I was on the late night show and the signal went all across the country. They said this, that, and the other. They said, 'Here are the clues,' and I laughed at them. I went on the air that night and I laughed at them. I said, 'This is ridiculous.' That night I went home and couldn't sleep. I couldn't get any rest. I thought, 'What are these kids talking about? What clues?' So, I went to my record cabinet and I started playing these records backwards as they had instructed me to and, sure enough, there emerged some very strange stuff....It was a big game in those days to uncover the clues. The kids told me, 'We hear you coming through loud and clear, why don't you blow the whistle on this?' So, I did. Oddly enough, on that same night somebody at The Tonight Show taping blurted from the audience, 'Paul is dead.' I was the first one to broadcast it to a lot of people. The switchboard at WABC was jammed. The program director came down in the middle of the night in his pajamas with an armed guard saying, 'Robey, you're creating a national panic! Get off the air!' I said, 'Fine! Fine! It's all right with me.' I said, 'By the way, this is going to be one heck of a station promotion for Halloween.'"

Not to be outdone, Alex Bennett of radio station WMCA-AM in New York City added fuel to this macabre rumor. He followed the trail of clues to London, in order to unearth more facts. Bennett was so involved in his pursuit that he stated, "The only way McCartney is going to quell the rumors is by coming up with a set of fingerprints from a 1965 passport which can be compared to his present prints." Bennett presented the so-called evidence to the public through his call-in radio show.

A whole cast of characters became involved in the search for death clues, as the wave of hysteria reached ever greater heights. Incredibly, there was a television special in which F. Lee Bailey questioned a number of witnesses, including Beatles' manager Allen Klein, and Peter Asher, the brother of Jane Asher, Paul McCartney's one-time fiancee, and member of the rock group Peter and Gordon. As Klein and Asher denied any and all evidence supporting the conclusion that Paul McCartney had met with a tragic demise, Gibb and fellow investigators took an active role in the telecast, and presented the grim evidence to the viewing public. At times Klein and Asher seemed bewildered as they tried to give a proper explanation for the preponderance of evidence gathered by Gibb, Fred Labour, and the other sleuths. The special ended with Bailey's suggestion that the public make up its own mind about the facts. Interestingly enough, no video copy of this television special remains. No one seems to remember what happened to the master tapes!

The evidence revolved around the theory that Paul McCartney had been decapitated in an automobile wreck after he left Abbey Road studios, apparently upset over an argument with the other Beatles. McCartney took a ride in his Aston Martin sports car and perished horribly in the ensuing accident. This accident supposedly took place in November 1966, most probably on a Tuesday. One version of the tragic accident has a despondent Paul picking up a female hitchhiker, who later unknowingly caused the accident by her overenthusiasm to get closer to the pop icon. The mystery girl's name was supposedly Rita, since in the song "Lovely Rita" from the Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band album McCartney sings, "I took her home. I nearly made it." Many listeners were convinced that this was another reference to the car crash.

According to William J. Dowlding's Beatle Songs, "McCartney did have a car crash on a Wednesday at 5 A.M. It happened on November 9, 1966, after an all-night recording session, and was coincidentally the morning after John met Yoko." As his sources, Dowlding cited H. V. Fulpen's The Beatles: An Illustrated Diary, and The Macs: Mike McCartney's Family Album, written by Michael McCartney, Paul's brother. According to Michael McCartney, Paul had a crash on a motorbike that caused "severe facial injuries to one half of his baby face."

In McCartney, Chris Salewicz gives the following description of the accident. It appears that sometime late in 1966 Paul was in Liverpool to spend a few days with his father. While there, Paul and Tara Browne, the Guinness heir, who was already at the McCartney home as a guest of Paul's brother Mike McCartney, had smoked a joint together one quiet evening and had then decided to ride a pair of mopeds to visit Paul's Aunt Bett. (Paul's stepsister, Ruth McCartney, claims that Paul and Browne had stopped at a nearby pub and had a few too many drinks.) Shortly before arriving at Aunt Bett's house, Paul lost control of his motorbike and was thrown across the handlebars into the street. McCartney landed on his face and received a nasty cut on his upper lip. Since this was just no accident victim, but a Beatle, the McCartney family realized that a private doctor would have to be called. This would avoid the mass of Beatlemania that would surely overwhelm the hospital. The doctor arrived at Aunt Bett's home, and stitched up the wound. A few months later, Paul was said to have grown his heavy mustache for Sgt. Pepper's cover to conceal the scar until it healed properly. It appeared that Paul also suffered a chipped tooth in the accident. In the "Paperback Writer" and "Rain" videos Paul appears to have a missing tooth. Of course, this gave yet more evidence to the great imposter theory, as did the noticeable scar that can be seen over Paul's upper lip in his individual photo from the White Album, released in 1968.

The biggest problem with the theory that Paul's death resulted from an automobile accident, not the simple motorbike crash, was the absence of any concrete evidence. Surely there were records -- a death certificate or autopsy report -- that could substantiate this bizarre occurrence. Another unanswered question dealt with the lack of eyewitnesses. Such an extraordinary occurrence would have proved very lucrative for any opportunistic spectator willing to cash in on his or her knowledge of the disastrous event. One unfounded rumor suggested that the charred remains of a young man had been found following a car crash. He was said to have received severe head injures, and that proper police identification was impossible due to the cadaver's missing teeth. Of course, there is no record of such an accident at that time, but this is yet one more clue to the ultimate urban legend of rock and roll.

On October 14, 1969, two days after the rumor broke on WKNR-FM, the Michigan Daily ran a review of the latest Beatles' album, Abbey Road. The review, written by Fred LaBour, took the form of an obituary, illustrated with a gruesome likeness of Paul's severed head. Fad songs with titles such as "St. Paul" by Terry Knight, later producer of Grand Funk Railroad, the ghoulish "Paulbearer," "So Long Paul," recorded by a young Jose Feliciano under the pseudonym Werbley Finster, and "Brother Paul," by Billy Shears and The All-Americans, were released in timely fashion. (Of course the reference to Billy Shears suggested the "imposter" who "stops the show" in the opening strains of the Beatles' "Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band.") "Brother Paul" was released by WTIX, a New Orleans radio station and had an advance order of 40,000 copies in the New Orleans area alone. It appeared that a dead Paul McCartney made for very good business!

It was unimaginable that the American public would believe such an unfounded rumor. However, this same generation had been raised on the questionable authority of the infamous Warren Commission report concerning the investigation of John F. Kennedy's assassination. If a conspiracy hiding the facts of an American president's murder existed, then why would it be out of the realm of possibility for the death of Paul McCartney to be hidden from the public? Just a year before, in 1968, America had lost Bobby Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr., two heroic figures, whose deaths many experts believed were the results of conspiracies. So, we questioned everything and we trusted no one -- especially those over thirty.

In the meantime, the Beatles had left the safe road of simple love songs and turned to the quest for social awareness. Once clean-cut "good boys," they now strongly opposed the war in Vietnam, and admitted their use of marijuana and LSD. John Lennon had even gone so far as to suggest that the Beatles were more popular than Jesus Christ: "Christianity will go. It will vanish and shrink. I needn't argue about that. I'm right and will be proved right. We're more popular than Jesus Christ now. I don't know which will go first, rock 'n' roll or Christianity. Jesus was all right, but his disciples were thick and ordinary. It's them twisting it that ruins it for me."

The sixties generation desperately needed something to believe in. Playboy created a furor when they released statements by the Beatles detailing other questionable beliefs, and made the masses realize for the first time the Beatles weren't the boys next door. At times, the Beatles made what some mothers would consider lewd comments about the Playboy playmates appearing in the centerfolds. They claimed that homosexuals could easily be identified in the United States by their crew-cut hair styles. The outrage demonstrated against John's Christianity comments brought forth rumors of Beatles' orgies with underage girls in the Beatles' hotel rooms. Yet again, many of these charges were ridiculous, but it seemed that in some cities, America was in the process of exorcizing its young from the grip of Beatlemania.

Far Eastern influences permeated the Beatles recordings from 1965 to 1967 like the pungent aroma of incense. George Harrison introduced the droning sounds of the sitar into Beatles' compositions. For the first time, the Beatles experimented with backward recordings and introduced metaphysical themes. However, not everyone was happy with this sudden change in the group.

The American public, it seemed, refused to allow change in its heroes. If there really was change in the Beatles, there had to be a reason for it. After the release of the Beatles' albums from 1967 to 1969, those adoring fans of the past became the inquisitors of the present. A scapegoat was demanded, and when the "Paul is dead" rumors surfaced in October 1969, those fans, filled with insecurity, were only too eager to search for the clues that provided the answer for this strange change in the Beatles' behavior.

The answer was obvious: Paul McCartney had indeed died, and an imposter had taken his place.

Copyright © 1996, 1998 by Gary Patterson

THE BRITISH INVASION AND THE AMERICAN MASS MEDIA

The Beatles were the musical messiahs of the turbulent sixties. John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison, and Ringo Starr led the British invasion that overran America's youth. No other British force, from Henry Clinton and George Cornwallis to Sir Edward Pakenham, accomplished so convincing a victory upon American soil. The method of conquest was not with fire and sword, but with electric guitars, amplifiers, and fab songs that infected every American household with the Mersey Beat.

American television, that unsuspecting British ally, innocently brought the Beatles into our living rooms on February 9, 1964, mainly due to the foresight of Ed Sullivan. But not even Sullivan, the promoter who introduced the American public to the likes of Robert Goulet and Elvis, foresaw the tidal wave that was about to hit American shores.

On that peaceful winter night, the home-viewing audience was said to have numbered well over seventy-three million Americans. Although a veteran of the television wars, Ed Sullivan must have been amazed that this British group was such a huge draw. Elvis Presley had set the record for the highest number of studio tickets requested: over seven thousand for his appearance in 1958. In what was a foreshadowing of things to come, the show had received over sixty thousand requests for tickets to the Beatle performance. Though some sources maintain that the television studio's seating capacity was only seven hundred, eight hundred tickets were given out through an impartial drawing, and those breathless individuals, chosen by fate, became live witnesses to the surrender of American youth.

The Beatles' form of rock and roll blazed like wildfire through record stores and television dance shows (American Bandstand; Ready, Steady, Go!; Hullabaloo; and Shindig). A new culture and art form, one that America sorely needed, was born.

The Beatles' moptop haircuts, Nehru jackets, and Cuban-heeled boots, not to mention their tight harmonies and melodies, helped combat the grief of a country still reeling from the untimely assassination of John F. Kennedy -- the president who, more than any other, symbolized an era of youth, hope, and opportunity.

Unfortunately, rock and roll proved to be just as susceptible to the same tragedies that seemed to infuse so many other aspects of American life during the sixties. On February 3, 1959, just a few miles outside Clear Lake, Iowa, Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and the Big Bopper perished in a fiery plane crash. The next year, Eddie Cochran died of injuries received in an automobile accident on April 17, 1960. Holly, Valens, the Big Bopper, and Cochran had all died tragically at the very height of their fame. On October 12, 1969 radio call-in lines across the country were backlogged with urgent requests from hysterical fans who demanded an answer to the same question: Had Beatle Paul McCartney died, too?

On October 12, 1969, Russ Gibb, disk jockey for Detroit's underground station WKNR-FM, received the phone call that would launch an unprecedented outbreak of hysteria throughout the pop world. The caller, who gave his name only as Tom, suggested that Gibb listen carefully to the fadeouts of certain Beatle songs. The Beatles' Abbey Road had just been released, but this early investigation concentrated on "Revolution 9" from The Beatles (the White Album) as well as the muffled murmuring at the conclusion of "Strawberry Fields Forever." As Gibb listened intently, he heard what seemed to be a number of references that seemed to suggest that Paul McCartney had met with an untimely end.

Many claim that one of the first written reports of the "Paul is dead" rumor was an article written by Tim Harper that appeared in a college newspaper in Des Moines, Iowa, on September 17, 1969. The article, "Is Paul Dead?" also appeared in the Chicago Sun-Times on October 21, 1969. WABC-AM (New York City) DJ Robey Younge also remembered receiving mysterious calls from some of his listeners begging him to help get the tragic story to the outside world. WABC-AM was a powerful station, especially at night, and could sometimes reach forty states with its broadcast signal. In an exclusive interview with my friend Joe Johnson for his syndicated Beatle Brunch radio program, Younge recounted his role in the McCartney mystery. "'Paul McCartney dead' is something I did one strange night after some kids had called me up from the Midwest, 'cause I was on the late night show and the signal went all across the country. They said this, that, and the other. They said, 'Here are the clues,' and I laughed at them. I went on the air that night and I laughed at them. I said, 'This is ridiculous.' That night I went home and couldn't sleep. I couldn't get any rest. I thought, 'What are these kids talking about? What clues?' So, I went to my record cabinet and I started playing these records backwards as they had instructed me to and, sure enough, there emerged some very strange stuff....It was a big game in those days to uncover the clues. The kids told me, 'We hear you coming through loud and clear, why don't you blow the whistle on this?' So, I did. Oddly enough, on that same night somebody at The Tonight Show taping blurted from the audience, 'Paul is dead.' I was the first one to broadcast it to a lot of people. The switchboard at WABC was jammed. The program director came down in the middle of the night in his pajamas with an armed guard saying, 'Robey, you're creating a national panic! Get off the air!' I said, 'Fine! Fine! It's all right with me.' I said, 'By the way, this is going to be one heck of a station promotion for Halloween.'"

Not to be outdone, Alex Bennett of radio station WMCA-AM in New York City added fuel to this macabre rumor. He followed the trail of clues to London, in order to unearth more facts. Bennett was so involved in his pursuit that he stated, "The only way McCartney is going to quell the rumors is by coming up with a set of fingerprints from a 1965 passport which can be compared to his present prints." Bennett presented the so-called evidence to the public through his call-in radio show.

A whole cast of characters became involved in the search for death clues, as the wave of hysteria reached ever greater heights. Incredibly, there was a television special in which F. Lee Bailey questioned a number of witnesses, including Beatles' manager Allen Klein, and Peter Asher, the brother of Jane Asher, Paul McCartney's one-time fiancee, and member of the rock group Peter and Gordon. As Klein and Asher denied any and all evidence supporting the conclusion that Paul McCartney had met with a tragic demise, Gibb and fellow investigators took an active role in the telecast, and presented the grim evidence to the viewing public. At times Klein and Asher seemed bewildered as they tried to give a proper explanation for the preponderance of evidence gathered by Gibb, Fred Labour, and the other sleuths. The special ended with Bailey's suggestion that the public make up its own mind about the facts. Interestingly enough, no video copy of this television special remains. No one seems to remember what happened to the master tapes!

The evidence revolved around the theory that Paul McCartney had been decapitated in an automobile wreck after he left Abbey Road studios, apparently upset over an argument with the other Beatles. McCartney took a ride in his Aston Martin sports car and perished horribly in the ensuing accident. This accident supposedly took place in November 1966, most probably on a Tuesday. One version of the tragic accident has a despondent Paul picking up a female hitchhiker, who later unknowingly caused the accident by her overenthusiasm to get closer to the pop icon. The mystery girl's name was supposedly Rita, since in the song "Lovely Rita" from the Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band album McCartney sings, "I took her home. I nearly made it." Many listeners were convinced that this was another reference to the car crash.

According to William J. Dowlding's Beatle Songs, "McCartney did have a car crash on a Wednesday at 5 A.M. It happened on November 9, 1966, after an all-night recording session, and was coincidentally the morning after John met Yoko." As his sources, Dowlding cited H. V. Fulpen's The Beatles: An Illustrated Diary, and The Macs: Mike McCartney's Family Album, written by Michael McCartney, Paul's brother. According to Michael McCartney, Paul had a crash on a motorbike that caused "severe facial injuries to one half of his baby face."

In McCartney, Chris Salewicz gives the following description of the accident. It appears that sometime late in 1966 Paul was in Liverpool to spend a few days with his father. While there, Paul and Tara Browne, the Guinness heir, who was already at the McCartney home as a guest of Paul's brother Mike McCartney, had smoked a joint together one quiet evening and had then decided to ride a pair of mopeds to visit Paul's Aunt Bett. (Paul's stepsister, Ruth McCartney, claims that Paul and Browne had stopped at a nearby pub and had a few too many drinks.) Shortly before arriving at Aunt Bett's house, Paul lost control of his motorbike and was thrown across the handlebars into the street. McCartney landed on his face and received a nasty cut on his upper lip. Since this was just no accident victim, but a Beatle, the McCartney family realized that a private doctor would have to be called. This would avoid the mass of Beatlemania that would surely overwhelm the hospital. The doctor arrived at Aunt Bett's home, and stitched up the wound. A few months later, Paul was said to have grown his heavy mustache for Sgt. Pepper's cover to conceal the scar until it healed properly. It appeared that Paul also suffered a chipped tooth in the accident. In the "Paperback Writer" and "Rain" videos Paul appears to have a missing tooth. Of course, this gave yet more evidence to the great imposter theory, as did the noticeable scar that can be seen over Paul's upper lip in his individual photo from the White Album, released in 1968.

The biggest problem with the theory that Paul's death resulted from an automobile accident, not the simple motorbike crash, was the absence of any concrete evidence. Surely there were records -- a death certificate or autopsy report -- that could substantiate this bizarre occurrence. Another unanswered question dealt with the lack of eyewitnesses. Such an extraordinary occurrence would have proved very lucrative for any opportunistic spectator willing to cash in on his or her knowledge of the disastrous event. One unfounded rumor suggested that the charred remains of a young man had been found following a car crash. He was said to have received severe head injures, and that proper police identification was impossible due to the cadaver's missing teeth. Of course, there is no record of such an accident at that time, but this is yet one more clue to the ultimate urban legend of rock and roll.

On October 14, 1969, two days after the rumor broke on WKNR-FM, the Michigan Daily ran a review of the latest Beatles' album, Abbey Road. The review, written by Fred LaBour, took the form of an obituary, illustrated with a gruesome likeness of Paul's severed head. Fad songs with titles such as "St. Paul" by Terry Knight, later producer of Grand Funk Railroad, the ghoulish "Paulbearer," "So Long Paul," recorded by a young Jose Feliciano under the pseudonym Werbley Finster, and "Brother Paul," by Billy Shears and The All-Americans, were released in timely fashion. (Of course the reference to Billy Shears suggested the "imposter" who "stops the show" in the opening strains of the Beatles' "Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band.") "Brother Paul" was released by WTIX, a New Orleans radio station and had an advance order of 40,000 copies in the New Orleans area alone. It appeared that a dead Paul McCartney made for very good business!

It was unimaginable that the American public would believe such an unfounded rumor. However, this same generation had been raised on the questionable authority of the infamous Warren Commission report concerning the investigation of John F. Kennedy's assassination. If a conspiracy hiding the facts of an American president's murder existed, then why would it be out of the realm of possibility for the death of Paul McCartney to be hidden from the public? Just a year before, in 1968, America had lost Bobby Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr., two heroic figures, whose deaths many experts believed were the results of conspiracies. So, we questioned everything and we trusted no one -- especially those over thirty.

In the meantime, the Beatles had left the safe road of simple love songs and turned to the quest for social awareness. Once clean-cut "good boys," they now strongly opposed the war in Vietnam, and admitted their use of marijuana and LSD. John Lennon had even gone so far as to suggest that the Beatles were more popular than Jesus Christ: "Christianity will go. It will vanish and shrink. I needn't argue about that. I'm right and will be proved right. We're more popular than Jesus Christ now. I don't know which will go first, rock 'n' roll or Christianity. Jesus was all right, but his disciples were thick and ordinary. It's them twisting it that ruins it for me."

The sixties generation desperately needed something to believe in. Playboy created a furor when they released statements by the Beatles detailing other questionable beliefs, and made the masses realize for the first time the Beatles weren't the boys next door. At times, the Beatles made what some mothers would consider lewd comments about the Playboy playmates appearing in the centerfolds. They claimed that homosexuals could easily be identified in the United States by their crew-cut hair styles. The outrage demonstrated against John's Christianity comments brought forth rumors of Beatles' orgies with underage girls in the Beatles' hotel rooms. Yet again, many of these charges were ridiculous, but it seemed that in some cities, America was in the process of exorcizing its young from the grip of Beatlemania.

Far Eastern influences permeated the Beatles recordings from 1965 to 1967 like the pungent aroma of incense. George Harrison introduced the droning sounds of the sitar into Beatles' compositions. For the first time, the Beatles experimented with backward recordings and introduced metaphysical themes. However, not everyone was happy with this sudden change in the group.

The American public, it seemed, refused to allow change in its heroes. If there really was change in the Beatles, there had to be a reason for it. After the release of the Beatles' albums from 1967 to 1969, those adoring fans of the past became the inquisitors of the present. A scapegoat was demanded, and when the "Paul is dead" rumors surfaced in October 1969, those fans, filled with insecurity, were only too eager to search for the clues that provided the answer for this strange change in the Beatles' behavior.

The answer was obvious: Paul McCartney had indeed died, and an imposter had taken his place.

Copyright © 1996, 1998 by Gary Patterson

Product Details

- Publisher: Touchstone (October 29, 1998)

- Length: 208 pages

- ISBN13: 9780684850627

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

Jay Fox ABC Fab Four Fridays A must read for any fan of the Fab Four.

Jim Zippo ABC Radio Network The Walrus Was Paul is loaded...[with] mind-blowing stuff....The best Beatle book yet!

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): The Walrus Was Paul Trade Paperback 9780684850627