Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

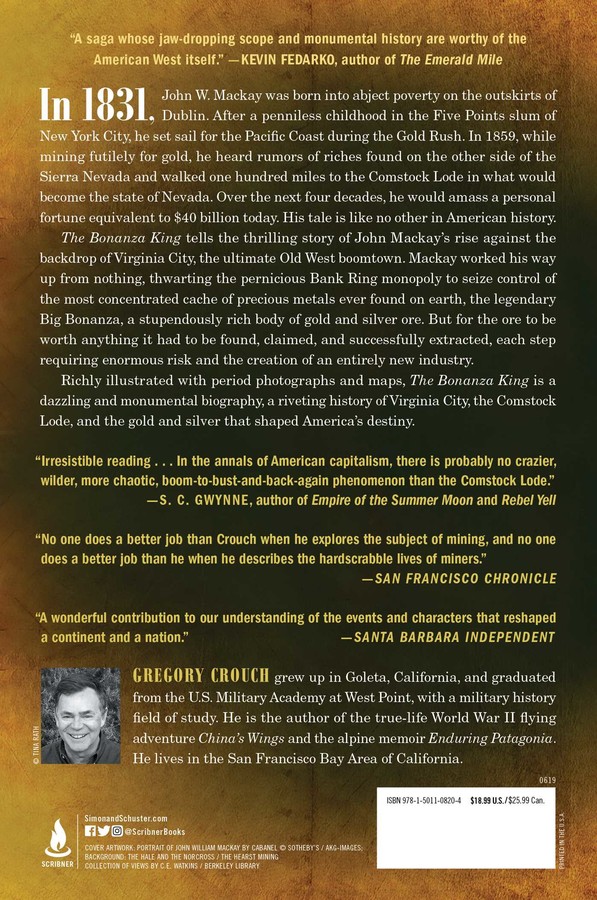

The Bonanza King

John Mackay and the Battle over the Greatest Riches in the American West

LIST PRICE $18.99

Free shipping when you spend $40. Terms apply.

Buy from Other Retailers

Table of Contents

About The Book

Born in 1831, John W. Mackay was a penniless Irish immigrant who came of age in New York City, went to California during the Gold Rush, and mined without much luck for eight years. When he heard of riches found on the other side of the Sierra Nevada Mountains in 1859, Mackay abandoned his claim and walked a hundred miles to the Comstock Lode in Nevada.

Over the course of the next dozen years, Mackay worked his way up from nothing, thwarting the pernicious “Bank Ring” monopoly to seize control of the most concentrated cache of precious metals ever found on earth, the legendary “Big Bonanza,” a stupendously rich body of gold and silver ore discovered 1,500 feet beneath the streets of Virginia City, the ultimate Old West boomtown. But for the ore to be worth anything it had to be found, claimed, and successfully extracted, each step requiring enormous risk and the creation of an entirely new industry.

Now Gregory Crouch tells Mackay’s amazing story—how he extracted the ore from deep underground and used his vast mining fortune to crush the transatlantic telegraph monopoly of the notorious Jay Gould. “No one does a better job than Crouch when he explores the subject of mining, and no one does a better job than he when he describes the hardscrabble lives of miners” (San Francisco Chronicle). Featuring great period photographs and maps, The Bonanza King is a dazzling tour de force, a riveting history of Virginia City, Nevada, the Comstock Lode, and America itself.

Excerpt

Tens of thousands of destitute Irish immigrants lived packed into the rickety tenements of Five Points in lower Manhattan. It was the most notorious slum in the world.

The poorest and most wretched population that can be found in the world—the scattered debris of the Irish nation.

—Archbishop John Hughes, 1849

Few great men ever started further down the ladder of success than John William Mackay. He was born into dire poverty near Dublin, Ireland, on November 28, 1831. Mackay, his younger sister, and his mother and father shared a crude cottage with the family pig. That was in no way unique, for grinding need wore at the foundations of nineteenth-century Ireland. Walls of loose-stacked stone slathered in mud enclosed the one-room shelters that housed fully half the Irish population. Most didn’t have windows. A roof of tree branches, sod, and leaky thatch protected them from the worst of the Atlantic rains; an open peat fire warmed them through the dark winter months. Beds and blankets were rare luxuries. Most Irish families slept on bare dirt floors alongside their domestic animals. A British government official reporting on the living conditions of the Irish peasantry noted that “in many districts their only food is the potato, their only beverage water. . . . Pigs and manure constitute their only property.” Like many Irish families, the Mackays didn’t always get enough to eat.

They were Catholic, and in the eyes of Ireland’s Gaelic Catholic majority, theirs was a conquered country, subjugated to the foreign English crown since the mid-seventeenth century. Although Catholics constituted more than three-quarters of Ireland’s population, by 1800, 95 percent of the country’s land had passed into the hands of English or Anglo-Irish Protestant aristocrats. Interested only in extracting rents and raising grain and cattle for cash sale in England, those absentee owners typically spent the bounty of the Irish countryside supporting lavish lifestyles in England while the laborers and tenants who worked their estates endured desperate poverty.

Irish tenants exchanged their labor for the lease on the small plots of dirt they needed to feed themselves. On such meager acreages, only the potato yielded sufficiently to feed a family. Poor Irish men and women ate them at almost every meal. Chronically indigent, often underfed, unable to purchase land, deprived of political power, and ferociously discriminated against for the sin of being Catholic, more than a million people left Ireland in the first four decades of the nineteenth century.

The Mackays held firm until 1840, but when young John reached the age of nine, the family immigrated to America. In 1800, some 35,000 Irish men and women lived in the United States. When the Mackay family arrived forty years later, that number had bloated to 663,000, the overwhelming majority of them poor and barely educated. Unskilled laborers nailed to the cross of extreme poverty, most Irish male immigrants did casual day labor, taking whatever employment they could find. Ten to twelve hours a day, six days a week, they performed the brutal, backbreaking toil nobody else would do, for paltry wages, digging sewers and canals, excavating foundations, loading ships and wagons, carrying hods of bricks and mortar for skilled masons, paving streets, and building railroad beds. Irish women worked as washerwomen and domestic servants, or sewed piecework in the needle trades. Widows took in boarders and collected rags they recycled into “shoddy,” a cheap cloth made from shredded scraps of wool. In New York City, Irish peddlers lugged merchandise to every neighborhood, hawking sweet corn, oranges, root beer, bread, charcoal, clams, oysters, buttons, thread, fiddle strings, cigars, suspenders, and a host of other inexpensive items. Rag-clad Irish children scavenged wood, coal, scrap metal, and glass, swept street crossings for tips, shined shoes, dealt apples and individual matches, and sold newspapers.

Rather than be grateful for their inexpensive labor and service, established Yankee Protestants despised the Irish immigrants, scorning them as “superstitious papists” and “illiterate ditch diggers.” The huge numbers of Irish-born Catholics enfranchised by the universal white male suffrage of Jacksonian democracy terrified native-born Americans. Many Protestants judged Catholicism—with its devotion to an imagined papal dictatorship—to be philosophically incompatible with the ideals of American democracy. Established, respectable Americans discriminated ferociously against the filthy Irish suddenly infesting the slums of eastern cities and manning the work camps of railroad- and canal-building concerns. Help wanted advertisements often carried the qualifier “any color will answer except Irish.” The twin millstones of being Irish and Catholic kept most Irish immigrants firmly anchored to the bottom of the American social spectrum.

In 1840, the year the Mackay family crossed the Atlantic, nearly half of the eighty-four thousand immigrants received in the United States came from tiny Ireland, and like thousands of their countrymen, the Mackays settled in New York City. The opening of the Erie Canal in 1825 had transformed the city into the most important port in the Western Hemisphere. Dense forests of masts and spars sprouted from ships docked against the piers, wharfs, quays, and slips cramming the southern shores of Manhattan Island. Banking, insurance, and manufacturing industries developed alongside the trade. New York’s population grew from 123,700 in 1820, five years before the canal opening, to 202,000 in 1830 and roughly 313,000 in 1840, making New York three times the size of Baltimore, America’s second largest urban concentration.

The Mackay family took quarters on Frankfort Street in the heart of the Fourth Ward. In their earliest days, the city’s Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth wards running from the East River to the Hudson River between City Hall Park and Canal Street had housed a mixed community of free blacks and French, German, Polish, and Spanish immigrants, but as more and more people abandoned Ireland for the United States, those neighborhoods acquired a distinctly Irish flavor, an influence that spread north into the Fourteenth Ward and east to permeate the Seventh. When the Mackays arrived in 1840, the Irish presence filled much of lower Manhattan,I and it centered on the Five Points intersection, just a few hundred yards from the Mackay family’s front door. At that time, Five Points was the most notorious slum in the United States.

Originally, Five Points had been an attractive marshy pond, the Collect. As the city expanded, tanneries and slaughterhouses set up on its banks and dumped their effluents into the pond. The Collect grew so disgusting that it depressed local real estate values. The municipality dug a canal to drain it (and gave a name to Canal Street), and when that didn’t improve conditions, filled in the pond. Without bedrock beneath it, the landfill proved too unstable to support major construction. Speculators bought the land and erected cheap one- to two-and-a-half-story wooden houses among the businesses of the neighborhood.

Property owners originally designed the houses for artisans, their families, and their workshops, but as budding manufacturing industries undercut the prosperity of individual craftsmen, landlords discovered that they made much larger profits by partitioning the buildings into tiny rooms rented to immigrants. Originally known as “tenant houses,” the term morphed into the word “tenements.” The rickety wooden fabrications were damp and frigid in winter, sticky and sweltering in summer, and always choked with foul, smoky air from the fires of cooking and warming. Inside, entire families crammed into single rooms entered from dim, lightless corridors. Unceasing din harried the inhabitants. Street noise reverberated in the front rooms. Rooms in the rear filled with the sounds of neighbors facing the backyards and alleys—spouses argued, babies screamed, siblings fought. Occupants shared filthy, overflowing outhouses with dozens of neighbors and drew water from common hydrants outside. The horses, mules, and oxen used everywhere for drayage defecated in the streets. The municipal government sponsored no garbage collection. Foot, animal, and wheeled traffic churned the improperly drained streets and alleys into fetid quagmires choked with animal corpses, human and animal waste, kitchen slops, and ashes. The stench was overwhelming.

Mice, rats, roaches, fleas, lice, maggots, and flies thrived in the squalor. Thousands of feral pigs roamed the streets. Despite the pigs’ grotesque snouts, coarse hair, and black-splotched skin, New York residents tolerated them because the pigs were far and away the city’s most effective street cleaners, even as they waged pitched battles with wild dogs for choice morsels of food. Among their own kind, the pigs rutted with loud, gleeful abandon. Refined Knickerbocker ladies sent up howls of protest, complaining that exposure to such indiscriminate sexual behavior undermined their respectability and lowered the moral tone of the whole city. For Irish women, most of whom had been raised in a rural countryside, fornicating domestic animals barely seemed worth a raised eyebrow. Besides, the pigs supplied valuable meat.

The outrageous quantities of animal and human feculence contaminated local wells. Dysentery, typhoid fever, diarrhea, and other waterborne diseases wreaked far more havoc in the immigrant wards than they did in the rest of the city, as did tuberculosis, diphtheria, smallpox, measles, mental disorders, and alcoholism. Crime and prostitution were ubiquitous, murder commonplace. Astronomical mortality rates haunted New York’s immigrant neighborhoods.

America’s new penny newspapers thrilled readers with lurid descriptions of the violence, dirt, mayhem, poverty, and moral depravity of Five Points. Visiting journalists could seldom resist characterizing the Irish neighborhoods as nests of vipers and sinks of filth and iniquity, unable or unwilling to do justice to the poor, working-class families who lived there. Most scribes, making brief forays into the slums, had eyes only for the dark side of the Irish wards. They failed to credit the immigrants’ ferocious struggle, or to perceive the community strength building in their churches, saloons, benevolent societies, fraternal orders, and fire companies. Immigrant families bent on improving their lot in the new country fought a constant battle to maintain any semblance of dignity in the face of such filth, squalor, and anarchic ruckus. The vast majority of Irish immigrants worked as hard as humanly possible to better their lives and the lives of their children as they fought to claw their way up from circumstances so desperate they were difficult for established Yankees to comprehend.

Among the thousands of immigrant families in New York City, the Mackays struggled forward in anonymity, and for their first two years in the United States, the family did reasonably well. Mr. and Mrs. Mackay scraped together enough money to send their ten-year-old son to school. In that, John Mackay was lucky. Only about half the school-age Irish children then living in New York City received any education at all.

Disaster struck the family in 1842. John Mackay’s father died of a cause lost to history. The catastrophe forced eleven-year-old John Mackay to quit school and work to support his mother and sister. Mackay could read, write, and figure, but he would never receive another day of classroom schooling. A taciturn lad who spoke slowly and awkwardly, fighting a stutter, he’d regret his lack of formal education for the rest of his life.

In an age devoid of social safety nets, when circumstances forced Irish boys not yet old enough to apprentice to earn money to help their family survive, most of them started selling newspapers or shining shoes. No resident of Frankfort Street would have been surprised that John Mackay fell into the world of the New York newsboys after his father’s death—most of the city’s newspapers had their headquarters on Park Row a few blocks west of the Mackay family lodgings.

For a job so near the bottom of the capitalist ladder, selling newspapers forced the young boys to accept a whopping ton of risk. Most New York dailies sold for two cents, and newsboys made a half-cent profit on every sale. However, wholesalers forced the newsboys to purchase their supply outright, for 1.5 cents per paper, and the newsboys couldn’t return unsold stock. Any newspapers they didn’t sell therefore cut a significant chunk from their earnings. The newsboys called it “getting stuck,” and they hated it. The more fortunate ones, like John Mackay, knew how to read, since basic literacy conveyed a major selling advantage. A literate newsboy could scan the leading stories and make a snap judgment about how many papers he’d sell. Ones who couldn’t read had to find a trusted ally to perform the service.

Newsboys bought their stock of morning papers before sunrise and immediately hit the streets crying the headlines, their clear, young voices among the all-pervasive sounds of the New York streets. Astute newsboys tailored their cries to their intended marks, touting commercial news at the approach of a Wall Street sharp or social happenings to a fashionable lady, and they all led a rough-and-tumble territorial existence. Newsboys staked claims to the best street corners and selling locales and fiercely defended their fiefdoms against interlopers. Fistfights were common, and John Mackay both received and administered his fair share of thrashings.

Midmorning, newsboys who had exhausted their stock grabbed a bite to eat and then hustled odd jobs—perhaps sweeping street crossings or carrying packages for tips at a ferry terminal—until the late papers dropped in the afternoon. They’d repeat their selling routine into the evening. An average newsboy, on an average day, earned twenty-five to fifty cents. A good salesman, on a good day, hustling hard until he’d sold his last paper, took home between sixty cents and a dollar. A day with incendiary headlines might earn a newsboy as much as two dollars.

Selling newspapers was an endless grind, but the newsboys reveled in their self-sufficient autonomy and liberty. Each boy worked on his own account, suffering no boss. Off-duty, they crowded the rowdy galleries of the Bowery and Chatham theaters, notorious aficionados of low entertainments and equally ardent spectators at prizefights and cockfights. A love of musical and dramatic productions and sporting entertainments, engrained as welcome relief from his sharp-elbowed New York upbringing, would persist for the rest of John Mackay’s life. The man he thought the greatest in the world was innovative newsman James Gordon Bennett, founder and owner of the New York Herald, a Scottish immigrant whom Mackay often watched hustle through City Hall Square with a bundle of newspapers tucked under his arm. Unnoticed, Mackay peddled Bennett’s newspaper on New York’s dirty streets.

John Mackay sold newspapers and scrounged odd jobs for four or five years. The Mackays eked out a living with John’s earnings and whatever money his sister and mother made in the needle trades or domestic service, but poor Irish immigrants struggling to scratch together a living was hardly a unique story in Manhattan in the middle 1840s. And street-level competition was about to get a whole lot more ferocious, because on the other side of the Atlantic, disaster had hit Ireland.

• • •

The nutrition of Irish tenant farmers and their families depended almost entirely on potatoes. Over the course of just a few days in the late summer of 1845, Ireland’s millions of subsistence farmers watched in horror as the leaves of previously healthy potato plants blackened, curled, and withered. Dug potatoes emerged from the ground full and healthy, but quickly shriveled to repulsive, inedible slime. The disease ravaged about half of the island’s potato crop in 1845. The next year, the blight destroyed nearly every potato in Ireland. An Gorta Mór, The Great Hunger, gripped the land.

Potato yields didn’t recover for five long years. The population of Ireland collapsed. Starvation and disease killed a million and a half Irish men, women, and children out of a prefamine population of about eight million. Another million fled the country, most to the United States, where they inundated the port cities of the eastern seaboard.II Fully 650,000 wretched Irish men, women, and children settled in New York City during the famine years.

Predictably, the influx provoked a backlash among native-born Americans. Anti-Catholic Yankees regarded the newest wave of destitute, starving refugees as “Saint Patrick’s vermin.” Many businesses—and some entire industries—refused to hire Irishmen. Conditions could hardly have been more difficult for a young Irish immigrant struggling to gain a toehold on an American adulthood. The first waves of famine immigrants arrived just as John Mackay reached the age at which he was old enough to apprentice. Without means or a secondary education, he needed a trade to carry him into adulthood, and the surge in anti-Irish sentiment made it harder to find a suitable apprenticeship. At the time, shipbuilding was one of New York’s most lucrative industries. An almost unbroken string of shipyards extended along the East River shoreline from just below Corlear’s Hook at the bend in the East River to the end of Twelfth Street. All were within reasonable walking distance of the family lodgings on Frankfort Street. Somehow, Mackay caught on as an apprentice ship’s carpenter at the William H. Webb shipyard, located on the East River between the ends of Fifth and Seventh streets. In that, he’d already accomplished something unusual—shipbuilders generally refused to employ Irishmen.

How Mackay overcame that obstacle isn’t clear. Whatever the reason, Webb provided an excellent opportunity. As Mackay advanced through the four or five years of his apprenticeship, his earnings would swell from fifty to seventy-eight cents per day. Although that didn’t greatly exceed newsboy earnings, an apprentice pulled in a guaranteed daily wage, and when Mackay had finished his term of service, as a qualified ship’s carpenter in an industry that seemed to promise lifetime employment, he could expect to earn two dollars per day, twice the amount earned by a common adult laborer. And of all of New York’s shipyards, Webb might have been the best place to learn the trade. Mariners considered William H. Webb the world’s best naval architect. Webb’s merchant packets, tea clippers, and sidewheel steamships brought new standards of engineering precision to a profession previously considered more art than science.

Out in the world beyond the shipyard, the United States had been fighting a war against Mexico since the spring of 1846. Major hostilities ground to a halt in the fall of 1847. U.S. forces had defeated and scattered Mexico’s armies and controlled most major Mexican cities. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo formally concluded the war on February 2, 1848. Its provisions gave the United States uncontested control of Texas, recognized the Rio Grande as the international border, and, in exchange for $15 million, ceded to the United States Mexico’s two northernmost provinces—Alta California and Santa Fe de Nuevo Mexico. The “Mexican Cession” added 1.2 million square miles to the United States—a landmass roughly equivalent to the size of western Europe—that included parts of the modern states of Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, and Wyoming, and the entireties of Utah, Nevada, and California.

Unbeknownst to both the Mexican and United States governments, nine days before they inked the treaty, an event of monumental import had occurred in California, in the obscure valley of Coloma in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada Mountains on the South Fork of the American River. At Coloma, millwright James Marshall supervised construction of a sawmill intended to serve the appetites of “Sutter’s Fort,” the hub of an agrarian colony managed by Swiss immigrant John Sutter centered at the confluence of the Sacramento and American rivers (at the site of the modern city of Sacramento). In the morning of January 24, 1848, a glimmer in the gravel of the mill’s tailrace caught Marshall’s eye. He pinched up a pebble of yellow metallic substance about half the size of a pea, then picked out a second piece. Marshall’s heart thumped; he was certain he’d found gold. Biting, hammering, boiling in lye, dousing with vinegar and nitric acid, and a specific gravity test proved the substance. Nothing in North America would ever be the same.

Within days, Marshall’s employees were using their free time to hunt gold flakes in the riverbed. Good, hardworking Mormons, they finished constructing the mill before quitting. John Sutter’s agrarian dream evaporated like fog as more and more of his employees abandoned wage labor in favor of gold mining. On March 2, several veterans of the Mormon Battalion—a volunteer unit that had marched to California from Iowa during the Mexican War—who had been working for Sutter since their discharge, struck a fabulously rich gold deposit at what became known as “Mormon Diggings” or “Mormon Island,” a bar of sand and gravel at a bend in the South Fork of the American River about fifteen miles below the sawmill. In the best pockets, the men scooped out gold dust by the glittering handful. Somehow, the Sierra foothills had kept their treasure hidden through seventy years of Spanish and Mexican administration.

Rumors of the gold strike reached the small outpost of San Francisco soon thereafter. A sleepy village sited at the northeastern tip of a long peninsula that divided the waters of the wild Pacific from the deep bay into which drained the Sacramento River, San Francisco had about eight hundred residents in early 1848, and it boasted two weekly newspapers, the Californian and the Star. The first public mention of the discovery appeared on the back page of the Californian on March 15, in a paragraph titled “GOLD MINE FOUND.” Wild stories circulated thereafter. The Star’s editor went to Coloma to investigate in April, but returned unimpressed, his exploratory party having traveled in company with John Sutter and unearthed only a few flakes of the desired metal. Attempting to check the story’s momentum, the Star’s May 6 issue declared “the gold fever . . . all sham.”

As of mid-May, skepticism held much of the population in check—until a Mormon named Sam Brannan took matters into his own hands. Brannan had arrived in San Francisco two years before, leading a group of 245 Mormon exiles who had made the long voyage around Cape Horn from New York. Brannan’s eye for business opportunity exceeded his religious ardor, however, and by May 1848, Brannan knew the gold excitement was no “humbug,” as went the then common term for fraud, trick, or sham. Miners down from the Sierra foothills paid for provisions at the store he’d opened at Sutter’s Fort with gold dust, and he’d personally visited Mormon Island. Brannan had decided to make money outfitting and provisioning miners, and he wanted more of them in the goldfields. On May 12, 1848, Brannan strode up San Francisco’s Montgomery Street, swinging his hat with one hand. In the other, he held aloft a quinine bottle filled with gold flakes, and he yelled, over and over, “Gold! Gold! Gold from the American River!”

Brannan held the proof in his hands. In California, the rush was on.

Sam Brannan had already bought every pick, shovel, and pan he could find. He became California’s first millionaire. Church elders expelled him from Mormon fellowship three years later.

The crucial detail was that nobody owned anything in the California interior, not the land, timber, or water, and certainly not the gold. (Everybody took it for granted that the native tribes inhabiting the area could be muscled aside.) Historically, kings, queens, and governments had reserved gold mines for themselves; California possessed no such entities. No laws regulated mining—or much of anything else—in California, and considering the recently expelled Mexican administration and the light hand of U.S. control, no entity possessed a shred of enforcement capability. For practical purposes, California had no government at all. California was a tabula rasa salted with gold, and gold mining required no capital investment except the effort to pick it up. On May 29, the Californian said, “The whole country, from Los Angeles to San Francisco and from the seashore to the base of the Sierra Nevadas, resounds with the sordid cry of ‘gold, Gold, GOLD!’ while the field is left half planted, the house half built, and everything neglected but the manufacture of shovels and pickaxes.” That was the Californian’s last issue. The newspaper’s employees vanished into the goldfields. The Star survived another fortnight, until June 14. The gold excitement carried off its staff, too.III

California’s social order collapsed. Virtually the entire male population of California’s coastal strip bolted for the goldfields. Deserted ships swung at anchor in San Francisco Bay. Tied to the pace of sail, steam, and steed, news of the gold discovery spread like disease, at the speed of human contact, reaching the Oregon Territory, the Sandwich Islands (Hawaii), Mexico, Peru, Chile, and Australia. Everywhere it touched, adventurous and avaricious souls contracted “the yellow fever,” dropped their business, and made haste for California.

• • •

On the other side of the continent, John Mackay and everyone else had no inkling of the momentous upheaval convulsing the Pacific Coast. The biggest event in the spring of 1848 for those whose lives orbited the Webb shipyard was a fire that swept the yard on April 8. The blaze started in a nearby stable and quickly spread, torching an office and storage loft. A pile of ship’s timbers caught fire. On the stocks nearby, ready for launch, stood the magnificent sidewheel steamships Panama and California, sister ships intended to inaugurate passenger, mail, and freight service between the Isthmus of Panama and the newly acquired territories on the Pacific Coast. Only the prodigious efforts of firemen and police saved the ships.

News of the gold discovery broke slowly in New York. Not until August 19, 1848, would careful readers of a two-column article describing “Affairs in Our New Territory” on the front page of the New York Herald be able to linger over a few surprising sentences, printed far down the second column, that mentioned a “gold mine discovered in December last . . . in a range of low hills forming the base of the Sierra Nevada”—assuming their perusal had survived dull tidbits touting California’s resources of quicksilver, silver, coal, copper, saltpeter, sulfur, asphaltum, limestone, soda springs, and salt.

Such an arid story didn’t provoke excitement. A much more incendiary article appeared a month later, on Monday, September 19, 1848, when the Herald published a letter from the Pacific Coast that described “gold for the gathering” and said that “he that can wield a spade and shake a dish can fill his pockets,” and admitted “only one serious apprehension, that we are in danger of having more gold than food.”

The rival Tribune printed a more official item the next day—a letter written from Monterey, California, on July 1 by former U.S. Consul Thomas O. Larkin and endorsed by Commodore Thomas Jones of the U.S. Navy. According to the letter, gold mining had stopped virtually all other work in California. “Three-fourths of the houses in the town of San Francisco are shut up,” Larkin wrote. On an inspection tour, Larkin had found more than a thousand people “digging and washing” for gold on the north and south forks of the American River. Larkin had also spent several consecutive days with eight miners working a branch of the Feather River. They operated two crude rockers, and every day he was with the eight men, Larkin witnessed each of their two rockers produce twelve to sixteen ounces of gold.

Considering gold’s value of $18 an ounce, each rocker was clearing $216 to $288 per day. Those were astronomical sums. Each man on the crew earned between $54 and $72 every day—fifty to seventy times the daily wage of the average unskilled laborer then working in New York.IV

Through September, October, and November, a steady stream of California stories captured public attention, but didn’t provoke wholesale migration: California was too far away, and the details seemed too farfetched to credit; nor could anyone discount the risk of hoax, error, or fraud—nineteenth-century newspapers regularly bent facts to boost sales, and prudent citizens kept an ever-skeptical eye on the nation’s army of shady promoters relentlessly touting the latest and greatest in land and stock sales, patent medicines, and newly created mechanical devices ripe for investment.

Popular skepticism changed on December 5, 1848, when President James K. Polk delivered his State of the Union address. The outgoing president’s accounting began with a self-congratulatory discourse on the “peace, plenty, and contentment” that “reign throughout our borders” and the “sublime moral spectacle . . . our beloved country” presented to the rest of the world. Polk, who had contended with rabid domestic opposition to the recently completed war with Mexico and faced a Congress bitterly divided over how to handle the admission of the new territories, whether as slave or free-soil, then segued into an extended justification of the benefits the conquests accrued to the United States. One of which was California. “The accounts of the abundance of gold in that territory are of such an extraordinary character as would scarcely command belief were they not corroborated by the authentic reports of officials in the public service who have visited the mineral district and derived the facts which they detail from personal observation.”

In other words, everything about gold in California was true. Newspapers carried transcripts of the president’s twenty-one-thousand-word address in its entirety. Simultaneously, the whole nation caught gold fever. “The gold of California . . . may strengthen and benefit, or it may deprave and destroy,” opined the Tribune.

To men and women, the gold would do all four. The rush of people hungry to cross a continent and make their fortunes would visit apocalyptic devastation on the Edenic landscapes of California—and give rise to a whole new civilization on the Pacific Coast.

• • •

John Mackay had these questions and others to ponder after the “Mechanics’ Bell” tolled the end of the ten-hour workday on December 6, 1848. (Shipyard employees erected the bell on a street corner near the shipyards in the 1830s after strikes won them the right to a ten-hour workday—few working-class men owned pocket watches; fewer trusted owners’ timekeeping.) Aided by the yellow glow of the city’s gas lamps, Mackay navigated home through what that day’s issue of the Tribune described as a “wilderness of filth”—the “uncovered sewers” and “putrid pollution” of the New York streets.

Such filth had suddenly become an object of serious concern. On December 1, the packet ship New York reached New York Harbor from France with seventeen or eighteen of its more than three hundred passengers infected with a disease that had already killed seven of those afflicted. The Board of Health quarantined the arrivals at Staten Island. The disease “resemble[d] Asiatic Cholera in all its symptoms.”

Although the dreaded scourge had been blessedly absent from North America for the preceding fourteen years, few words provoked as much terror as “cholera.” The sickness’s 1832–34 visitation had killed more than thirty-five hundred in New York City. Nationwide, tens of thousands had died. From one stride to the next, an apparently healthy person could be felled by explosive, uncontrollable diarrhea, vomiting, and agonizing cramps. Half of the stricken died, many within a day. Some died within hours. Since few people possessed the courage to minister to the afflicted, and most of those who did contracted the disease themselves, the majority of cholera victims died a horrid death, alone and caked in excrement. The plague had ravaged Europe through the summer and fall of 1848, seemingly shackled to the violent popular uprisings shaking the despotic governments of the continent, until it jumped to England in October. Few doubted its power to vault the Atlantic.

Among the quarantined passengers of the New York, four new cases—and three deaths—occurred the day the president’s address appeared in the Tribune. From the Battery to Murray Hill and from West Street to Kips Bay, “the three C’s”—Congress, cholera, and California—dominated conversation.

A letter from California’s military governor, Colonel Richard Barnes Mason, ran in the Tribune on December 8. Colonel Mason told of the goldfield tour he’d made in company with an obscure army lieutenant named William Tecumseh Sherman. They’d found the vanished population of California’s coastal strip in the Sierra foothills, where Colonel Mason estimated that four thousand people were digging and washing gold from the beds of the Feather, Yuba, Bear, American Fork, and Cosumnes rivers, averaging one to three ounces of gold per person, per day. He mentioned one spot where two men had raised $17,000 in two days, another location that had produced $12,500, and a third where $2,000 came out in three weeks. “I might tell of hundreds of similar occurrences,” he added. One man showed him fourteen pounds of clean-washed gold. Another returned to Monterey with thirty-seven pounds—the fruit of seven weeks of labor. A soldier on twenty-day furlough from the Monterey garrison earned $1,500, even though he’d spent half his time traveling. The value of the gold that that soldier mined exceeded the total of the rations, pay, and clothing he’d receive during his entire five-year enlistment.

The gold was on land belonging to the United States government. Colonel Mason mused about trying to extract a tax, but “considering the large extent of country, the character of the people engaged, and the small scattered force at my command, I resolved not to interfere, but to permit all to work freely.

“No capital is required to obtain this gold,” he added. “The laboring man wants nothing but his pick and shovel and tin pan with which to dig and wash the gold, and many frequently pick gold out of the crevices of rocks with their butcher knives, in pieces from 1 to 6 ounces.”

The courier who brought the initial dispatches from California had also arrived with a tea caddy filled with gold—233 ounces of it. A Mr. David Carter, apparently a private citizen who had traveled with the courier, brought 1,980 ounces, a whopping 123.75 pounds of gold. Both samples went to the U.S. Mint in Philadelphia for assay.

The Mint silenced the “sneers of the unbelievers” when it telegraphed the War Department a summary of its findings: “Genuine.”

• • •

Suddenly, there was a place to go. No longer the slow, plodding creep of a rough frontier edging away from the settled eastern states, the West had taken an almighty bound, overstepping a continent, to a land of glittering promise lining the shores of a distant ocean where a man might pick up more wealth in a morning than he could earn in a lifetime of eastern drudgery.

A flood of California-themed advertisements filled the newspapers. More ominously, another advertisement touted an “Infallible Remedy for the Asiatic Cholera.” Many passengers sequestered at Staten Island had fled quarantine, and the cholera already had a foothold in the city, at a German boardinghouse at the corner of Cedar and Greenwich. The disease seemed unlikely to confine itself to the location.

By December 14, just eight days after the publication of the president’s address, in New York Harbor alone, forty-five vessels were outfitting for Panama or California direct, through the Straits of Magellan or around Cape Horn. The gold mania built through the Christmas season, the New Year, and the first months of 1849. Names of men departing for California filled column after column of the New York newspapers. Reporters made much of teary-eyed departures on the city’s docks and piers. Men unwilling to chance the storms of Cape Horn or the pestilential jungles of Panama—or unable to pay the passage fees—headed to the frontier towns of the Missouri River from which they could undertake the two-thousand-mile overland crossing to California.

“The spirit of emigration, which is carrying off thousands to California, so far from dying away increases and expands every day,” said the Herald on January 11, 1849. “All classes of our citizens seem to be under the influence of this extraordinary mania.”

The rush to California was the biggest event in the history of the young Republic. John Mackay stayed at the shipyard through all of it. His time was yet to come.

I. Described in terms of modern New York City neighborhoods, the Irish concentration comprised most of Chinatown and Tribeca as well as the southern portions of SoHo, the Bowery, Little Italy, and the Lower East Side.

II. Ireland’s population fell by nearly 50 percent between 1841 and 1926, from 8.18 million to 4.23 million. Ireland still hasn’t recovered—its population today is about 2 million less than it was before the potato famine.

III. Sam Brannan owned the Star. A few months later, the remnants of the Californian and the Star consolidated into a new newspaper—the Daily Alta California.

IV. Calculating based on the 2017 gold value of about $1,250 per ounce, each one of those rockers was earning between $15,000 and $20,000 per day—or between $3,750 and $5,000 per man, per day, sums for which many of us would walk across a continent and risk death.

Product Details

- Publisher: Scribner (June 4, 2019)

- Length: 480 pages

- ISBN13: 9781501108204

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

“A compelling, multifaceted story rich in detail, texture, and history…a wonderful contribution to our understanding of the events and characters that reshaped a continent and a nation.” —Santa Barbara Independent

“Crouch excels in documenting the life of a 19th-century capitalist who wished to find success, treat his workers fairly, and make advancements in science and technology. Fans of American history, the American West, or business will find Mackay’s life story inspiring.” —Library Journal

“Crouch presents a well-written and laudatory biography of a remarkable and admirable man.” —Booklist

“A thorough tribute to the life and work of an honest man who earned his fortune and kept his good name in an era of fierce competition and astounding corruption.” —Publishers Weekly

“Admirers of scrupulous entrepreneurship will find much of value in this book…full of useful pointers on how to treat people and build an enduring legacy and fortune.” —Kirkus Reviews

“In the annals of American capitalism, there is probably no crazier, wilder, more chaotic, boom-to-bust-and-back-again phenomenon than the Comstock Lode. Gregory Crouch has given us the definitive story of the man who clawed his way to the top of all that madness, and he has done it in a way that makes for irresistible reading.” —S.C. Gwynne, author of Empire of the Summer Moon and Rebel Yell

“The cattle towns of Dodge City and Cheyenne have lodged in American memory as epitomizing the “wild West,” but they were sedate as 1950s Scarsdale in comparison with the silver Golconda of Washoe, which contained the Comstock Lode—in the 1860s, the richest couple of square miles on earth. In the struggle to extract the metal from Nevada’s impervious rock, and to own it once it was out, Gregory Crouch finds a story of violence and high color and national significance, a tale of industrial genius and breathtaking rascality that is engrossing from start to finish. Crouch’s swift, strong, lucid prose makes problems of metallurgy and mineshaft framing seem as lively as a gunfight, and the rise of his Irish immigrant hero, John Mackay, from the mire of a New York City slum to become one of the wealthiest men in the world has all the elements of a preposterous fantasy—save that it is entirely true. Moreover, in a brass-knuckles era of peril and general scurrility, Mackay was always as honest as he was tough, and so among its many other pleasures The Bonanza King offers a heartening saga of virtue rewarded.” —Richard Snow, author of Iron Dawn and I Invented the Modern Age

“There are plenty of marvelous legends that surround the gold rushes of California and Alaska, the copper mines of Arizona, and the silver deposits of Deadwood and Leadville. But in the end, there was only one Comstock Lode—and like the men who hacked out the ore chambers more than a thousand feet beneath Virginia City, Gregory Crouch has brought to the surface a glittering, grit-encrusted, and utterly glorious tribute to the greatest trove of precious metals ever discovered in the United States. The Bonanza King drills unerringly through the human themes that cut across the heart of this narrative, from ambition and corruption to ingenuity and greed, braiding together a saga whose jaw-dropping scope and monumental history are worthy of the American West itself.” —Kevin Fedarko, author of The Emerald Mile

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): The Bonanza King Trade Paperback 9781501108204