Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

Table of Contents

About The Book

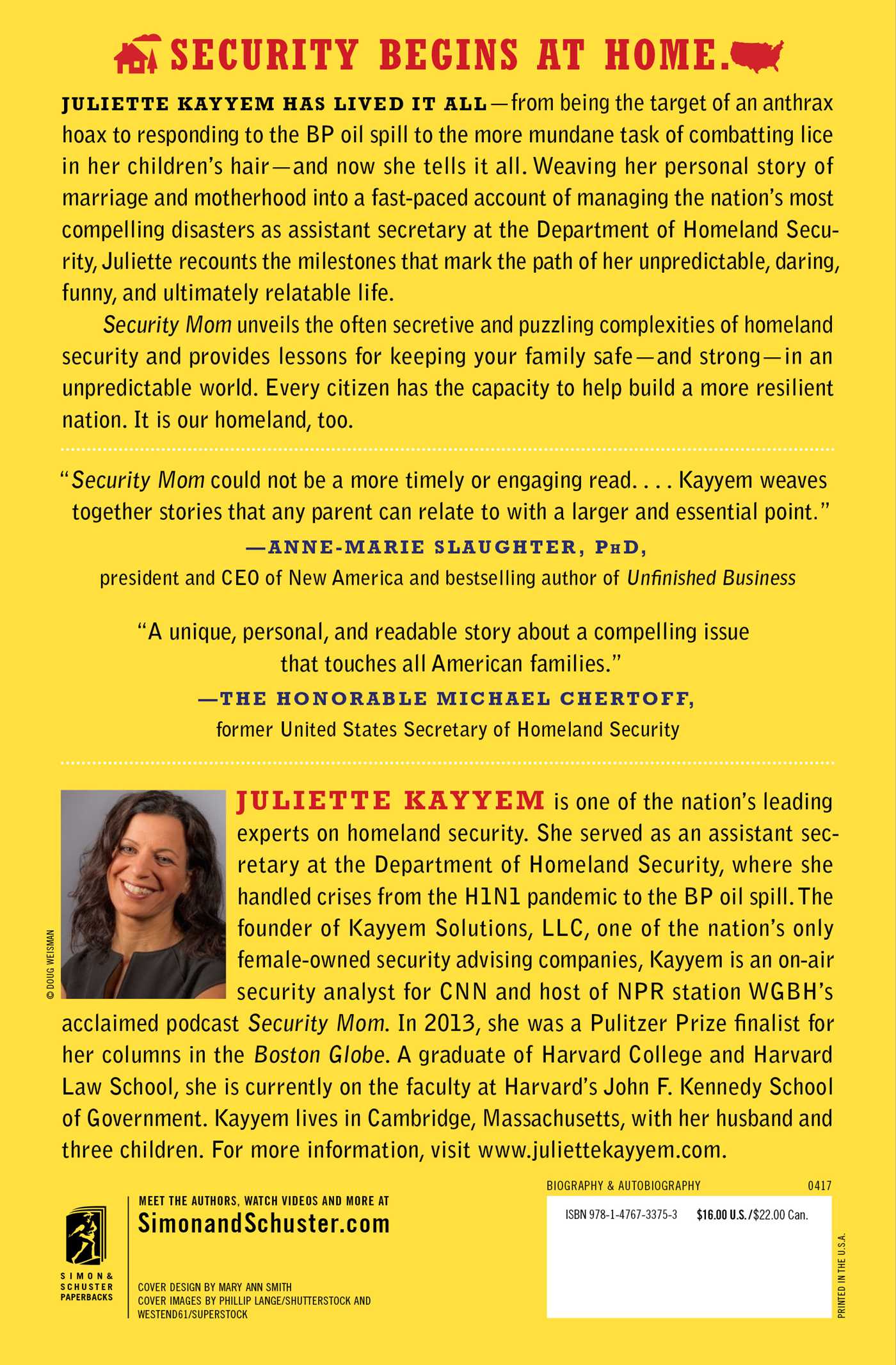

In “a lively debut…[with] plenty of enthusiastic ‘can-do’ advice” (Publishers Weekly), a Homeland Security advisor and a Pulitzer Prize–nominated columnist—and mother of three—delivers a timely message about American security: it begins at home.

Soccer Moms are so last decade. Juliette Kayyem is a “Security Mom.” At once a national security expert who worked at the highest levels of government, and also a mom of three, she’s lived it all—from anthrax to lice to the BP oil spill—and now she tells it all with her unique voice of reason, experience, and humility.

Weaving her personal story of marriage and motherhood into a fast-paced account of managing the nation’s most perilous disasters, Juliette recounts the milestones that mark the path of her unpredictable, daring, funny, and ultimately relatable life.

Security Mom is modern tale about the highs and lows of having-it-all parenthood and a candid, sometimes shocking, behind-the-scenes look inside the high-stakes world of national security. In her signature refreshing style, Juliette reveals how she came to learn that homeland security is not simply about tragedy and terror; it is about us as parents and neighbors, and what we can do every day to keep each other strong and safe. From stocking up on coloring books to stashing duplicate copies of valuable papers out of state, Juliette’s wisdom does more than just prepare us to survive in an age of mayhem—it empowers us to thrive. “You got this,” Juliette tells her readers, providing accessible advice about how we all can better prepare ourselves for a world of risks.

Soccer Moms are so last decade. Juliette Kayyem is a “Security Mom.” At once a national security expert who worked at the highest levels of government, and also a mom of three, she’s lived it all—from anthrax to lice to the BP oil spill—and now she tells it all with her unique voice of reason, experience, and humility.

Weaving her personal story of marriage and motherhood into a fast-paced account of managing the nation’s most perilous disasters, Juliette recounts the milestones that mark the path of her unpredictable, daring, funny, and ultimately relatable life.

Security Mom is modern tale about the highs and lows of having-it-all parenthood and a candid, sometimes shocking, behind-the-scenes look inside the high-stakes world of national security. In her signature refreshing style, Juliette reveals how she came to learn that homeland security is not simply about tragedy and terror; it is about us as parents and neighbors, and what we can do every day to keep each other strong and safe. From stocking up on coloring books to stashing duplicate copies of valuable papers out of state, Juliette’s wisdom does more than just prepare us to survive in an age of mayhem—it empowers us to thrive. “You got this,” Juliette tells her readers, providing accessible advice about how we all can better prepare ourselves for a world of risks.

Excerpt

Security Mom THE MAKING OF A TERRORISM EXPERT

I AM A “SECURITY MOM.”

The term first went mainstream in the 2004 presidential election, to describe a voting bloc of women who were white, suburban, and with children, and who were really, really worried about terrorism. They didn’t do much about it but worry a lot. Did I mention that they worried? Occasionally, when the world was less than stable, they might actually freak out: I have this image of the smart and funny main character in I Love Lucy turning into a hapless scaredy-cat when she sees a mouse, and then screaming to her manly husband—“Ricky!”—for protection. These college-educated women—whether single, married, divorced, or widowed—just threw up their hands and cowered like the very children they were so worried about protecting. And despite the fact that this population is usually defined by its natural inclination toward progressive social causes, when it came to the war in Iraq and concern over the war on terror, they largely voted Republican.

It isn’t clear whether security moms were actually a deciding factor in the 2004 George W. Bush versus John Kerry presidential election. No matter. The security mom became a cultural and marketing phenomenon. And she was utterly defenseless in an age of terror.

Screw that. We need a new definition.

“Security mom” can and should mean a woman who plans and prepares as she raises her children in a world where anything can happen. Exceptionally rational, a security mom views the yellow sticky note as god’s greatest invention since the slow cooker. Whether she works or not, she isn’t defenseless, waiting for someone else to protect her. There are security dads too, trust me, and security singles and security partners and security grandparents. The list goes on. They are all out there. They just don’t know it.

Yet.

I am not the same person I was in 2001, when terror first struck our homeland so vividly, when those of us already a part of the “terrorism expert” class suddenly became relevant. My thinking about security has changed significantly since then; I have come to realize that a nation too focused on preventing bad things from happening is on a fool’s errand. Instead, we should simply, but resourcefully, reclaim our resiliency. I call this “grip”—it’s a more active, more in-your-face, more powerful form of resiliency. We prepare, respond, adapt, and then brace for the next thing. We practice these habits of grip. We know that nothing goes according to plan. Sh-t happens: that is the profound knowledge that defines a security mom.

A nation that empowers its citizens with this knowledge becomes a safer nation as a whole. Imagine a nation built around the notion that “sh-t happens,” a nation that did not view the often violent jolts to our systems—hurricanes, and oil spills, and terrorists, and viruses, and earthquakes—as abnormal, but as always the possible consequences of living in a globally interconnected society. Imagine if we understood that invulnerability is impossible and instead focused on how to reduce risk and respond to crises when they inevitably happen, with vigor. Imagine if every citizen then felt empowered to implement strategies of preparedness, knowing, as we surely do, that something, anything could happen.

I am so often asked: “Are we safe?” This question has plagued me for my entire career. It has been asked by family and friends, students and scholars, news anchors and government officials.

The most accurate answer is, “Of course not; what kind of question is that?” But I get why it’s asked. Us “real” experts—and you can put whatever descriptor you want in front, whether it be “homeland security,” “national security,” “terrorism,” “aviation,” “hurricane,” “public health,” “military,” “crisis”—have too often sold a vision of society that has never existed. Sure, we can be safer, but we can never be safe.

We are a homeland like no other—a federal structure with fifty governors, all kings and queens unto themselves; hundreds of cities with transit systems that only function when on time; frantic commercial activity crisscrossing borders on roadways, railways, and airways; the expectation of every working mother that when she orders yet another iPhone 6 charger on Amazon.com, it will arrive the next day; and, oh yes, the desire that our nation not just focus on security but also attend to schools, health care, transportation, civil rights and civil liberties, and every other large and small concern voiced by its citizens. America is built to be unsafe, and thank goodness for that.

Over the years, as terrorist attacks and related incidents grew in frequency—maybe because we called it a “war”—something happened to make the public feel powerless and disinvested in its own safety. The experts, like me, are partially to blame. People in my field uphold a culture of paternalism that has done much to protect the public, but much more to ignore it.

We—meaning the band of homeland security experts that I had been a part of—somehow convinced the public that the responsibility for their security, and the security of this inherently unsafe nation, could be fully delegated. Too many on both sides—the public and the experts—believed it. That belief came with a rising cost: We completely neglected to educate Americans about homeland security. We dismissed Americans’ capacity to learn, to engage, to act. As a consequence, the substantive benefits of resiliency were not explained; the habits of grip were not nurtured.

The safety of our nation is dependent on skills that we already practice to keep ourselves and our children safer at home, in our communities. And those of us who work in homeland security failed to disclose this one basic fact: You are a security expert, too. You are familiar with these skills. You know the refrains of every parent: Look both ways, wear your helmet, call when you get there. But rather than building on the practices of security cultivated in nearly every household, homeland security was treated as if it had less and less to do with what happened in our homes. The result was to make us more—not less—vulnerable.

So much ink has been spilled over how we can prevent harm from coming our way. So little has been disclosed about what happens when that harm comes to pass. I can debate until I’m bored with myself about the need for climate mitigation measures, stronger gun control, or a more vigorous public health system. Yes, we live in an age of exceptional danger, but it takes a certain amount of amnesia to believe we are unique in this regard. The truth is we have always been vulnerable. In this sense, homeland security is also much like home security—both are built on the mistakes of the past and forward lessons learned for the future. My own mother likes to remind me, after I leave her with “recommendations” for how to look after my kids when she offers to babysit, that she has some experience in this field. Our mothers learned from theirs, as we surely learn from ours, and as our children will surely learn from us. No generation is particularly exceptional in figuring this out; all we can do is try to avoid making the same mistakes twice.

The warning that keeps sounding, year after year, generation after generation, is this: No government ought to guarantee perfect security, because no government can provide it. There has never been a time of perfect peace. Indeed, there is only one promise that government should make: that it will invest in creating a more resilient nation. And that promise begins with acknowledging that citizens must be a part of this plan. For any society to be more resilient, the public must be briefed. They must assume a certain amount of responsibility for their safety and adopt the habits of grip. We can cross our fingers and hope for the best, but I don’t believe in luck—not, at least, as a tactic for safety in the homeland or in my home.

But I wasn’t so sure how to relate these messages. How could I explain that we all had the capacity to build more resilient communities, one home at a time, using the same skills we have mastered at home: grip, flexibility, planning, backup plans? Then, in 2011, my cousin Karen wrote me an e-mail. The subject line read: “Al Qaeda.”

Karen is a little older than me, with daughters who are already out of college. She is a dentist, and she has, over the years, scolded me for barely flossing. Thankfully, she also gives me great advice for how to address my deteriorating gum situation (see above re: flossing). I try to return the favor when I can.

“Hi Juliette,” she began. She continued:

Can you help? Debbie is in Pennsylvania and she wants to go to NYC for the weekend. But I just saw that they think there could be a ten-year anniversary attack there, so I don’t want her to go. She says I am crazy. I said I would contact you. Would you send your kids? By the way, how are your gums? Are you flossing? Don’t forget to sleep with your night guard. And let me know about the terrorists.

Dental care and bin Laden: never before have the two been so closely aligned. But there was something illuminating in Karen’s questions. She wanted to assume a certain amount of responsibility for her daughter’s safety, but she didn’t know where to begin. Her e-mail clarified what I had always suspected—there is something missing from our nation’s security efforts.

Karen just wanted the lowdown: Tell me about these scary things, whether they are terrorists, natural disasters, or viruses. Tell me how it works and what I should do to protect my loved ones. Tell me what you would do if it was your child who wanted to travel this weekend. Tell me just like I would tell you about your gums.

Simply: Bring it home.

I have served at the highest levels of state and federal government in homeland and national security—for one governor, Deval Patrick, and two presidents, Bill Clinton and Barack Obama. I have also raised three children. Their birth years coincide with traumatic events in American history: Cecilia was born in 2001, just a few weeks after we lost three thousand citizens when two planes flew into the World Trade Center in New York, another plane destroyed parts of the Pentagon, and another was lost in the fields of Pennsylvania. Leo arrived in 2003, as US troops, deployed by an administration looking for revenge above anything else, invaded Iraq. Jeremiah came into this world in 2005, soon after Hurricane Katrina, the deadliest hurricane in America’s history, devastated the Gulf Coast. Celebration and destruction link my own home with my homeland.

As the governor’s homeland security advisor, I oversaw my state’s National Guard and, on his behalf, authorized the deployment of troops abroad; I am also a master at the game Battleship, mercilessly mobilizing fleets and defeating my kids. As President Obama’s assistant secretary for homeland security, I have done my time in the Situation Room; I have also spent endless hours in local emergency rooms, once after Leo used Jeremiah’s head as a football. I have been cleansed in a post–radiation exposure shower after an unfortunate (though thankfully a false-positive test result) experience in a nuclear facility—but I found getting lice out of all my children’s hair after an unfortunate sleepover much more debilitating.

I have spent my career protecting my home and homeland, and I want to share what I have learned. My hope is that through these stories, my experiences in the strange and secretive world of homeland security—more maligned than understood—will become accessible to the American public. It is time we made this whole scary, confusing, seemingly idiotic, totally unapproachable apparatus personal. I have simply come to believe that the challenges, conflicts, and choices inherent in protecting the homeland are really not that different from those we encounter every day. The touchstones of protecting both—grip, preparedness, spare capacity, flexibility, communication, learning from the past—are essentially the same.

And with that, I present myself as Exhibit A.

I must first concede that I am an unlikely terrorism expert. I am still consistently surprised that my professional career focuses on violent events, from the threat of terrorism to other, wide-ranging threats including climate change and mass shootings.

I was born and raised in Los Angeles, California, where I spent afternoons and weekends at the beach, playing volleyball and working on my tan. I grew up at a time when skin cancer seemed a remote-enough possibility that my girlfriends and I would slather ourselves in baby oil instead of sunscreen. I dreamed of being a professional volleyball player, a zoologist, a Russian scholar (I dropped that after a short-lived and academically disastrous foray into the language), and then a lawyer. At my all-girls high school, I had teachers with first names like “King” and last names like “Wildflower.” It was California in the 1980s.

I am the daughter of an immigrant family—my mother was born in Lebanon, and my dad’s family also came from there, though they would actually meet in a carpool to UCLA, which they both attended as students. My parents prioritized academics, and were strict enough to make me spend one weekend night home with them throughout my high school career. I was a dedicated student, got good grades, played varsity sports, and even spent a summer at debate camp, for which my cooler older sister, Marisa, still teases me. I was eventually accepted at Harvard College, and I moved to Cambridge. Though I have drifted back and forth to DC during Democratic administrations, I have remained in Massachusetts ever since.

Massachusetts is where I met my husband, David, when I was nineteen. I am mortified to admit it was at the Harvard-Yale football game—at the tailgate, no less. It all sounds so predictable, but at that age, we had our ups and downs, breakups and makeups, and ultimately, after attending Harvard Law School together, we moved down to DC to work in the Clinton administration’s Justice Department. We rented an apartment, bought IKEA furniture, got married.

I was twenty-six when I made my initial foray into government. My first legal job had nothing to do with security in the traditional sense. In 1995, I began as an attorney in the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice. Assistant Attorney General Deval Patrick was my boss; Janet Reno was attorney general. I flew around the country on behalf of the federal government litigating for the protection of citizens’ rights, mostly in schools. While I worked on long-standing desegregation cases—from St. Louis to Mississippi—I also contributed to more novel litigation, including opening up the Citadel and the Virginia Military Institute to female cadets. I was allowed to initiate the federal government’s first peer-on-peer violence (what we now call “bullying”) case against a California school district that turned a blind eye toward its football team’s behavior. Previously, civil rights cases had only been brought against school districts that directly violated students’ rights. In this case, I determined that a federal civil rights action could be initiated against a school district that failed to protect students from other students. The district eventually settled, and instituted tougher rules to protect female students from the physical and verbal harassment of its football team.

I loved my job. I loved my husband. Essentially, I loved our life. I thought my future would unfold rather predictably: I would spend my career championing civil rights and working for the progressive causes that had inspired me to attend law school in the first place. It didn’t. I soon learned, as I explained above, that nothing goes according to plan. Sh-t happens.

On April 19, 1995, just a few months before I began at the Justice Department, Timothy McVeigh and his cohorts bombed Oklahoma City’s Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building, killing 168 people and injuring another 300. This was homegrown terrorism, but it furthered a slow awakening, initiated after the first terrorist attack on the World Trade Center in 1993, of our vulnerabilities at home. Because the issues surrounding McVeigh’s actions were politically difficult to address—right-wing extremism, domestic radicalization, gun control—in the aftermath of that tragedy, Congress deflected and passed the Omnibus Counterterrorism Act of 1995, which addressed immigration and foreign terrorism instead.

The act gave the FBI the power to detain non–US citizens indefinitely, even if they were here lawfully, based on secret evidence—evidence so secret that it would not be disclosed to the defendant in a court of law. In the years after it was passed, the number of terrorists charged under the act was relatively small: A dozen men, all Muslim and all from Arab countries, were detained without the opportunity to refute the evidence against them. Because they were not US citizens, the argument held, they did not have the same Fifth Amendment right to cross-examination that a US citizen would have. These prosecutions came to be known as the “secret evidence” cases.

One case highlighted the ease with which the legislation’s flawed logic could be exploited. The judge—the only party besides the prosecutors authorized to see the “secret evidence”—disclosed in ruling against the United States that the highly classified “smoking gun” in the case consisted of testimony by the man’s ex-wife. The judge ruled that the wife, surely aware that accusing her husband of terrorism would earn her full custody of their children, was not a reliable source as to her husband’s “terrorist” status.

As more and more judges exposed the errors of these prosecutions, Attorney General Janet Reno intervened. After all, these were all federal cases, and the US attorneys who built (and lost) these cases reported to her. Arab and Muslim political groups, such as the Arab American Institute and the American Muslim Political Action Committee, publicly criticized the act; they met with Reno several times during the latter part of Clinton’s second term. Reno sympathized with their complaints. She had spent her professional career in a courtroom where an open, if adversarial, spirit reigned; this particular use of classified information challenged her legacy. By 1998, Reno decided to exercise her tremendous authority to investigate the consequences of this piece of legislation, mainly in her own department.

By then, I had contributed to some high-profile cases as a civil rights litigator and line attorney at the Justice Department. I was also, incidentally, the only high-ranking Arab-American at the Justice Department when Reno turned her attention to the Omnibus Counterterrorism Act. She asked me to join her daily 8:15 a.m. all-hands meeting, where her senior team convened to discuss a range of litigation activities—from anti-trust to civil rights to environmental protection. I regularly arrived a few minutes late, with wet hair (at twenty-nine and with no kids, 8:15 a.m. seemed early to break out the blow-dryer).

Reno put me on a team charged with reviewing the “secret evidence” cases. We examined how the FBI investigated these individuals, and whether these actions constituted a proper use of its authority. I would sit in a room secured for classified information with colleagues from the national security apparatus, poring over the files of these cases. Our mandate was to declassify as much material as possible and to determine whether the cases were actually legitimate exercises of governmental authority. My background in civil rights law proved immediately helpful. Most civil rights cases, after all, are brought against government entities such as housing authorities or police departments or, as was true of the “secret evidence” cases, the FBI.

That review appointment made two things clear. First, as an Arab-American who now had an intimate understanding of the complex legal and operational issues surrounding our national security, I could act as a bridge between groups such as the Arab American Institute and the American Muslim Political Action Committee and the government. The Arab-American community was starting to organize, and they sought increased access to government officials to press their agenda on a variety of topics, including Middle East peace, civil rights, and hate crime legislation. While I did not professionally identify as Arab-American, nor did I work with or for the political groups clamoring for recognition, I had the right heritage and the right credentials for this role.

Second, I was becoming a “terrorism expert.” As my work drew me deeper into the national security apparatus, I became privy to information about the threats to our nation from various terrorist organizations thriving abroad and at home, as well as about the amount of activity—surveillance, intelligence operations, military actions, law enforcement raids—being performed to protect the country.

At first, it was hard for me to reconcile these new roles with the career trajectory I had once imagined. I’d spent hours in law school defending prisoners in administrative hearings against corrections officers. I’d spent the summer after my first year in law school in Montgomery, Alabama, working on death penalty appeals for lawyer and Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption author Bryan Stevenson. I boarded at the home of Virginia Durr, the white activist who helped bail out Rosa Parks after she was arrested on that bus in 1955. Indeed, the first time I encountered anything related to terrorism was outside the office. The “Unabomber,” Ted Kaczynski, had added my scientist brother, Jon Faiz Kayyem, to a list of potential targets, and, after Kaczynski’s arrest in 1996, the government wanted to make sure there were no unopened boxes around his house.

I was not born to be a terrorism expert. I simply morphed into one, in stages.

Stage One: Admission. Literally.

I applied for and was eventually granted top-secret security clearance. This wasn’t a test of academic prowess or firearms acumen or language skills. It was a lot of forms—a series of questions to be answered under penalty of perjury. Some of these were tedious: I had to list all places of residence for the last fifteen years. Others were simply silly: I had to swear that I had never supported the Communist Party or advocated the downfall of the United States.

Only one made me groan, and then laugh: I had to list my foreign-born relatives. My mother, born Milly Deeb, has eight brothers and sisters. As I wrote down the birthplaces of my aunts and uncles, I traced my family’s path to America:

Eddie

Kooba, Lebanon (in the Batroun District)

Alice

Havana, Cuba

Libby

Kooba, Lebanon

Carrie

Kooba, Lebanon

Milly (my mother)

Kooba, Lebanon

Rosie

Kentucky, United States

George

Kentucky, United States

Janice

Kentucky, United States

Georgette

Kentucky, United States

This list still cracks me up. It looks so nefarious without context. I imagined a distraught FBI agent reading my clearance papers, trying to piece together the strange journey that led my family from Lebanon to Cuba, back again to Lebanon, and finally to Kentucky.

I was asked, predictably, for more information. So began a seemingly endless back-and-forth about my family’s exodus so many decades ago. The men and women charged with granting security clearance needed proof of my statements on the form. So I obliged: old passports, documents, aged papers from decades past, notarized written statements when nothing else could be found. Even when I thought I was done, I received requests for more proof: travel logs, social security numbers, records of foreign business interests, marriage certificates, and driver’s licenses. And once wasn’t enough. Security clearances are regularly updated, and as I rose in the government over the years, the reviews became more rigorous—proof, more proof, and even more proof.

My mother’s mother, Rose—or, as I called her, Situ, which means “grandmother” in some dialects of Arabic—and my grandfather were young and poor when they left Lebanon for the first time in 1929. They traveled to Cuba, hoping to make their way to America after two previous attempts had been thwarted. Before Castro assumed power, Cuba promised easy access to America for immigrants in search of a better life. Notices in newspapers throughout the developing world lured adventure seekers to Cuban shores, advertising a pit stop on the way to the Promised Land. It turned out this was a ruse; access to the United States was no easier from Cuba than it was from Lebanon. My grandparents stayed in Havana long enough for my grandmother to give birth to their second child. Older now but still poor, and with no family in Cuba, they returned to Lebanon in 1932. They would stay there long enough to welcome three more children, including my mother.

My mother was their last child born in Kooba, a small mountain village where neighbors greeted guests for tea with a selection of fresh mints and a range of cigarette boxes. Their house was the size of a few parking spaces. (In fact, when I visited years later, it actually had been demolished to build two parking spaces.) When my mother was just one, the family accomplished from Lebanon what they couldn’t from Cuba and, with papers in hand, arrived at Ellis Island.

Or at least, this is what I thought for most of my life. The myths immigrant families create to explain their journeys to new lands cannot be easily verified. My mother and her family had always told one story, which culminated in their arrival on the great island that had welcomed so many before them. Had we scrutinized further, we would have noticed that Situ’s documents showed a different route through the port of New York. The ruse was discovered not by the enterprising FBI agent who pored over my clearance papers but by a curious uncle fascinated with the family tree.

Here’s the kicker: Situ lived a long time, and she must have known that we were all perpetuating the Ellis Island lie. Her journey from Lebanon to Cuba to America was a source of great pride. She had overcome countless obstacles to bring her family here. My grandparents belonged to a generation of immigrants that became Americans, and their supposed arrival on Ellis Island was an important signifier of that new identity. So I can understand why she might not have been inclined to correct this mistake. It also made for a great story.

I know, for a fact, that the next part of that great story is true: The Deebs settled in Kentucky, where the weather was appealing. Kentucky is horse country, which must have felt familiar to so many Arabs who raised and groomed these animals before arriving in America. The Deebs did not last long in Kentucky—nor did my grandparents’ marriage. I can only imagine how bad their relationship became, for Situ willingly divorced my grandfather and raised nine children on her own. No one speaks of Eli, my grandfather. I have never seen a picture of him. He holds no place in my head or my heart, and years later, when David and I proposed to name our second son Eli because we liked the name, I was surprised when my mother looked at me fiercely and said “You will not name him that.” I had forgotten about my grandfather. We were taught to look forward, not back.

Like so many others, the Deebs went west. Situ had had her first child at age fourteen; the age difference between her and her eldest son, Edward, was ten years less than the age difference between her eldest and her youngest child. She is remembered by more than one hundred children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren. (“Juliette who?” I am sometimes asked when I attend a crowded family event in Los Angeles. “Oh, you’re Milly’s youngest.”)

There is, of course, another side to my family: the Kayyems. I was also required to produce proof of their journey to America. My paternal grandfather, Faiz, was born in Lebanon (or possibly some part of Syria), and married my grandmother, also named Rose, a much younger beauty. The exact nature of his business varied; he was in textiles from Japan, silk from China, real estate in Hawaii. He was, by all accounts, successful, if not impatient. He moved his family into nine different rental homes, requiring my dad to attend eight different schools by the time he graduated high school. My dad was raised in Hawaii and California, where he would eventually meet my mother. My parents may have come from the same corner of the world, but they were raised under very different circumstances.

Strict and domineering, Faiz roused a rebellious spirit in my dad that has animated him for his entire life. Consider, as I did while filling out those forms, the notorious story of my father’s arrest. As a college student, he was once accused of robbery and assault on a policeman. The charge was unsubstantiated and soon dismissed after he was held for two days—it turns out my dad had lost his wallet close to the scene of the crime. But this episode engendered a lasting habit among all Kayyems: we are skeptical of first reports (in my dark-haired dad’s case, the assailant was described as “redheaded”), a legacy that has served me well throughout my career. My father’s childhood boasted other incidents that proved of little interest with regard to my security clearance, thankfully. There were fistfights in Catholic schools; more than one near-death experience in the ocean around Hawaii; and pictures of him from the 1970s with a moustache, large collars, and cigarettes (before he and my mother embraced the healthy lifestyle that makes them very youthful seventy-plus-year-olds today). Simply put, my dad knew how to have fun, in his own way. One time, as an experiment, my dad tried to fit my older brother, Jon Faiz; my sister, Marisa; and me on his Harley Davidson for a ride around West Los Angeles. The experiment worked, but then he had to face my mother.

As I finished the last question on those painfully long forms, I was actually thankful for the opportunity to retrace my family’s journeys. It was a way to acknowledge how the Kayyem and Deeb histories have shaped my professional beliefs. My ancestors lived in a country with a long and painful legacy of civil war, and I grew up listening to stories that taught me people are more resilient than we might expect. My opposition to the 2003 Iraq War grew from my knowledge of Lebanon’s sad history of occupation. I spent many dinners with Arabs who could have told the war’s planners not to expect roses in the streets of Baghdad, and I listened. I support comprehensive immigration reform because I recognize how this nation thrives when it welcomes those who wish to immigrate. Not so long ago, my family chose this country as their home. I have seen the statistics and I believe profiling is ineffective at best, unlawful at worst. I have also seen how many people are profiled—like my brother, Jon Faiz, when he is unshaven. I take issue with the NYPD’s nicely named “Demographics Unit,” which targeted Muslim and Arab communities. It was an unsuccessful program. I knew it would be, because I know—from Situ’s experience—that America’s greatest strength is its acceptance of all religions and creeds.

When I turned in my completed forms, I sat down with the FBI agent to discuss my security clearance. He had already interviewed my friends, neighbors, and family, who had doubly validated my claims. The agent congratulated me. “Welcome to the club,” he said.

It didn’t feel like true acceptance—more like my proof had held up, for now. The vagaries of my security clearance review, the journey it unearthed, meant that I would always feel that I had one foot firmly in the security world, but that the other lingered behind, tethered to my history, my background, my identity, my family, my home. I didn’t know it then, but I would spend the rest of my career trying to become someone who could fit into all these worlds: the daughter of an immigrant family, an East Coast transplant from California, a young bride to her college sweetheart, a public servant, a security expert, and, eventually, a mother.

I AM A “SECURITY MOM.”

The term first went mainstream in the 2004 presidential election, to describe a voting bloc of women who were white, suburban, and with children, and who were really, really worried about terrorism. They didn’t do much about it but worry a lot. Did I mention that they worried? Occasionally, when the world was less than stable, they might actually freak out: I have this image of the smart and funny main character in I Love Lucy turning into a hapless scaredy-cat when she sees a mouse, and then screaming to her manly husband—“Ricky!”—for protection. These college-educated women—whether single, married, divorced, or widowed—just threw up their hands and cowered like the very children they were so worried about protecting. And despite the fact that this population is usually defined by its natural inclination toward progressive social causes, when it came to the war in Iraq and concern over the war on terror, they largely voted Republican.

It isn’t clear whether security moms were actually a deciding factor in the 2004 George W. Bush versus John Kerry presidential election. No matter. The security mom became a cultural and marketing phenomenon. And she was utterly defenseless in an age of terror.

Screw that. We need a new definition.

“Security mom” can and should mean a woman who plans and prepares as she raises her children in a world where anything can happen. Exceptionally rational, a security mom views the yellow sticky note as god’s greatest invention since the slow cooker. Whether she works or not, she isn’t defenseless, waiting for someone else to protect her. There are security dads too, trust me, and security singles and security partners and security grandparents. The list goes on. They are all out there. They just don’t know it.

Yet.

I am not the same person I was in 2001, when terror first struck our homeland so vividly, when those of us already a part of the “terrorism expert” class suddenly became relevant. My thinking about security has changed significantly since then; I have come to realize that a nation too focused on preventing bad things from happening is on a fool’s errand. Instead, we should simply, but resourcefully, reclaim our resiliency. I call this “grip”—it’s a more active, more in-your-face, more powerful form of resiliency. We prepare, respond, adapt, and then brace for the next thing. We practice these habits of grip. We know that nothing goes according to plan. Sh-t happens: that is the profound knowledge that defines a security mom.

A nation that empowers its citizens with this knowledge becomes a safer nation as a whole. Imagine a nation built around the notion that “sh-t happens,” a nation that did not view the often violent jolts to our systems—hurricanes, and oil spills, and terrorists, and viruses, and earthquakes—as abnormal, but as always the possible consequences of living in a globally interconnected society. Imagine if we understood that invulnerability is impossible and instead focused on how to reduce risk and respond to crises when they inevitably happen, with vigor. Imagine if every citizen then felt empowered to implement strategies of preparedness, knowing, as we surely do, that something, anything could happen.

I am so often asked: “Are we safe?” This question has plagued me for my entire career. It has been asked by family and friends, students and scholars, news anchors and government officials.

The most accurate answer is, “Of course not; what kind of question is that?” But I get why it’s asked. Us “real” experts—and you can put whatever descriptor you want in front, whether it be “homeland security,” “national security,” “terrorism,” “aviation,” “hurricane,” “public health,” “military,” “crisis”—have too often sold a vision of society that has never existed. Sure, we can be safer, but we can never be safe.

We are a homeland like no other—a federal structure with fifty governors, all kings and queens unto themselves; hundreds of cities with transit systems that only function when on time; frantic commercial activity crisscrossing borders on roadways, railways, and airways; the expectation of every working mother that when she orders yet another iPhone 6 charger on Amazon.com, it will arrive the next day; and, oh yes, the desire that our nation not just focus on security but also attend to schools, health care, transportation, civil rights and civil liberties, and every other large and small concern voiced by its citizens. America is built to be unsafe, and thank goodness for that.

Over the years, as terrorist attacks and related incidents grew in frequency—maybe because we called it a “war”—something happened to make the public feel powerless and disinvested in its own safety. The experts, like me, are partially to blame. People in my field uphold a culture of paternalism that has done much to protect the public, but much more to ignore it.

We—meaning the band of homeland security experts that I had been a part of—somehow convinced the public that the responsibility for their security, and the security of this inherently unsafe nation, could be fully delegated. Too many on both sides—the public and the experts—believed it. That belief came with a rising cost: We completely neglected to educate Americans about homeland security. We dismissed Americans’ capacity to learn, to engage, to act. As a consequence, the substantive benefits of resiliency were not explained; the habits of grip were not nurtured.

The safety of our nation is dependent on skills that we already practice to keep ourselves and our children safer at home, in our communities. And those of us who work in homeland security failed to disclose this one basic fact: You are a security expert, too. You are familiar with these skills. You know the refrains of every parent: Look both ways, wear your helmet, call when you get there. But rather than building on the practices of security cultivated in nearly every household, homeland security was treated as if it had less and less to do with what happened in our homes. The result was to make us more—not less—vulnerable.

So much ink has been spilled over how we can prevent harm from coming our way. So little has been disclosed about what happens when that harm comes to pass. I can debate until I’m bored with myself about the need for climate mitigation measures, stronger gun control, or a more vigorous public health system. Yes, we live in an age of exceptional danger, but it takes a certain amount of amnesia to believe we are unique in this regard. The truth is we have always been vulnerable. In this sense, homeland security is also much like home security—both are built on the mistakes of the past and forward lessons learned for the future. My own mother likes to remind me, after I leave her with “recommendations” for how to look after my kids when she offers to babysit, that she has some experience in this field. Our mothers learned from theirs, as we surely learn from ours, and as our children will surely learn from us. No generation is particularly exceptional in figuring this out; all we can do is try to avoid making the same mistakes twice.

The warning that keeps sounding, year after year, generation after generation, is this: No government ought to guarantee perfect security, because no government can provide it. There has never been a time of perfect peace. Indeed, there is only one promise that government should make: that it will invest in creating a more resilient nation. And that promise begins with acknowledging that citizens must be a part of this plan. For any society to be more resilient, the public must be briefed. They must assume a certain amount of responsibility for their safety and adopt the habits of grip. We can cross our fingers and hope for the best, but I don’t believe in luck—not, at least, as a tactic for safety in the homeland or in my home.

But I wasn’t so sure how to relate these messages. How could I explain that we all had the capacity to build more resilient communities, one home at a time, using the same skills we have mastered at home: grip, flexibility, planning, backup plans? Then, in 2011, my cousin Karen wrote me an e-mail. The subject line read: “Al Qaeda.”

Karen is a little older than me, with daughters who are already out of college. She is a dentist, and she has, over the years, scolded me for barely flossing. Thankfully, she also gives me great advice for how to address my deteriorating gum situation (see above re: flossing). I try to return the favor when I can.

“Hi Juliette,” she began. She continued:

Can you help? Debbie is in Pennsylvania and she wants to go to NYC for the weekend. But I just saw that they think there could be a ten-year anniversary attack there, so I don’t want her to go. She says I am crazy. I said I would contact you. Would you send your kids? By the way, how are your gums? Are you flossing? Don’t forget to sleep with your night guard. And let me know about the terrorists.

Dental care and bin Laden: never before have the two been so closely aligned. But there was something illuminating in Karen’s questions. She wanted to assume a certain amount of responsibility for her daughter’s safety, but she didn’t know where to begin. Her e-mail clarified what I had always suspected—there is something missing from our nation’s security efforts.

Karen just wanted the lowdown: Tell me about these scary things, whether they are terrorists, natural disasters, or viruses. Tell me how it works and what I should do to protect my loved ones. Tell me what you would do if it was your child who wanted to travel this weekend. Tell me just like I would tell you about your gums.

Simply: Bring it home.

I have served at the highest levels of state and federal government in homeland and national security—for one governor, Deval Patrick, and two presidents, Bill Clinton and Barack Obama. I have also raised three children. Their birth years coincide with traumatic events in American history: Cecilia was born in 2001, just a few weeks after we lost three thousand citizens when two planes flew into the World Trade Center in New York, another plane destroyed parts of the Pentagon, and another was lost in the fields of Pennsylvania. Leo arrived in 2003, as US troops, deployed by an administration looking for revenge above anything else, invaded Iraq. Jeremiah came into this world in 2005, soon after Hurricane Katrina, the deadliest hurricane in America’s history, devastated the Gulf Coast. Celebration and destruction link my own home with my homeland.

As the governor’s homeland security advisor, I oversaw my state’s National Guard and, on his behalf, authorized the deployment of troops abroad; I am also a master at the game Battleship, mercilessly mobilizing fleets and defeating my kids. As President Obama’s assistant secretary for homeland security, I have done my time in the Situation Room; I have also spent endless hours in local emergency rooms, once after Leo used Jeremiah’s head as a football. I have been cleansed in a post–radiation exposure shower after an unfortunate (though thankfully a false-positive test result) experience in a nuclear facility—but I found getting lice out of all my children’s hair after an unfortunate sleepover much more debilitating.

I have spent my career protecting my home and homeland, and I want to share what I have learned. My hope is that through these stories, my experiences in the strange and secretive world of homeland security—more maligned than understood—will become accessible to the American public. It is time we made this whole scary, confusing, seemingly idiotic, totally unapproachable apparatus personal. I have simply come to believe that the challenges, conflicts, and choices inherent in protecting the homeland are really not that different from those we encounter every day. The touchstones of protecting both—grip, preparedness, spare capacity, flexibility, communication, learning from the past—are essentially the same.

And with that, I present myself as Exhibit A.

I must first concede that I am an unlikely terrorism expert. I am still consistently surprised that my professional career focuses on violent events, from the threat of terrorism to other, wide-ranging threats including climate change and mass shootings.

I was born and raised in Los Angeles, California, where I spent afternoons and weekends at the beach, playing volleyball and working on my tan. I grew up at a time when skin cancer seemed a remote-enough possibility that my girlfriends and I would slather ourselves in baby oil instead of sunscreen. I dreamed of being a professional volleyball player, a zoologist, a Russian scholar (I dropped that after a short-lived and academically disastrous foray into the language), and then a lawyer. At my all-girls high school, I had teachers with first names like “King” and last names like “Wildflower.” It was California in the 1980s.

I am the daughter of an immigrant family—my mother was born in Lebanon, and my dad’s family also came from there, though they would actually meet in a carpool to UCLA, which they both attended as students. My parents prioritized academics, and were strict enough to make me spend one weekend night home with them throughout my high school career. I was a dedicated student, got good grades, played varsity sports, and even spent a summer at debate camp, for which my cooler older sister, Marisa, still teases me. I was eventually accepted at Harvard College, and I moved to Cambridge. Though I have drifted back and forth to DC during Democratic administrations, I have remained in Massachusetts ever since.

Massachusetts is where I met my husband, David, when I was nineteen. I am mortified to admit it was at the Harvard-Yale football game—at the tailgate, no less. It all sounds so predictable, but at that age, we had our ups and downs, breakups and makeups, and ultimately, after attending Harvard Law School together, we moved down to DC to work in the Clinton administration’s Justice Department. We rented an apartment, bought IKEA furniture, got married.

I was twenty-six when I made my initial foray into government. My first legal job had nothing to do with security in the traditional sense. In 1995, I began as an attorney in the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice. Assistant Attorney General Deval Patrick was my boss; Janet Reno was attorney general. I flew around the country on behalf of the federal government litigating for the protection of citizens’ rights, mostly in schools. While I worked on long-standing desegregation cases—from St. Louis to Mississippi—I also contributed to more novel litigation, including opening up the Citadel and the Virginia Military Institute to female cadets. I was allowed to initiate the federal government’s first peer-on-peer violence (what we now call “bullying”) case against a California school district that turned a blind eye toward its football team’s behavior. Previously, civil rights cases had only been brought against school districts that directly violated students’ rights. In this case, I determined that a federal civil rights action could be initiated against a school district that failed to protect students from other students. The district eventually settled, and instituted tougher rules to protect female students from the physical and verbal harassment of its football team.

I loved my job. I loved my husband. Essentially, I loved our life. I thought my future would unfold rather predictably: I would spend my career championing civil rights and working for the progressive causes that had inspired me to attend law school in the first place. It didn’t. I soon learned, as I explained above, that nothing goes according to plan. Sh-t happens.

On April 19, 1995, just a few months before I began at the Justice Department, Timothy McVeigh and his cohorts bombed Oklahoma City’s Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building, killing 168 people and injuring another 300. This was homegrown terrorism, but it furthered a slow awakening, initiated after the first terrorist attack on the World Trade Center in 1993, of our vulnerabilities at home. Because the issues surrounding McVeigh’s actions were politically difficult to address—right-wing extremism, domestic radicalization, gun control—in the aftermath of that tragedy, Congress deflected and passed the Omnibus Counterterrorism Act of 1995, which addressed immigration and foreign terrorism instead.

The act gave the FBI the power to detain non–US citizens indefinitely, even if they were here lawfully, based on secret evidence—evidence so secret that it would not be disclosed to the defendant in a court of law. In the years after it was passed, the number of terrorists charged under the act was relatively small: A dozen men, all Muslim and all from Arab countries, were detained without the opportunity to refute the evidence against them. Because they were not US citizens, the argument held, they did not have the same Fifth Amendment right to cross-examination that a US citizen would have. These prosecutions came to be known as the “secret evidence” cases.

One case highlighted the ease with which the legislation’s flawed logic could be exploited. The judge—the only party besides the prosecutors authorized to see the “secret evidence”—disclosed in ruling against the United States that the highly classified “smoking gun” in the case consisted of testimony by the man’s ex-wife. The judge ruled that the wife, surely aware that accusing her husband of terrorism would earn her full custody of their children, was not a reliable source as to her husband’s “terrorist” status.

As more and more judges exposed the errors of these prosecutions, Attorney General Janet Reno intervened. After all, these were all federal cases, and the US attorneys who built (and lost) these cases reported to her. Arab and Muslim political groups, such as the Arab American Institute and the American Muslim Political Action Committee, publicly criticized the act; they met with Reno several times during the latter part of Clinton’s second term. Reno sympathized with their complaints. She had spent her professional career in a courtroom where an open, if adversarial, spirit reigned; this particular use of classified information challenged her legacy. By 1998, Reno decided to exercise her tremendous authority to investigate the consequences of this piece of legislation, mainly in her own department.

By then, I had contributed to some high-profile cases as a civil rights litigator and line attorney at the Justice Department. I was also, incidentally, the only high-ranking Arab-American at the Justice Department when Reno turned her attention to the Omnibus Counterterrorism Act. She asked me to join her daily 8:15 a.m. all-hands meeting, where her senior team convened to discuss a range of litigation activities—from anti-trust to civil rights to environmental protection. I regularly arrived a few minutes late, with wet hair (at twenty-nine and with no kids, 8:15 a.m. seemed early to break out the blow-dryer).

Reno put me on a team charged with reviewing the “secret evidence” cases. We examined how the FBI investigated these individuals, and whether these actions constituted a proper use of its authority. I would sit in a room secured for classified information with colleagues from the national security apparatus, poring over the files of these cases. Our mandate was to declassify as much material as possible and to determine whether the cases were actually legitimate exercises of governmental authority. My background in civil rights law proved immediately helpful. Most civil rights cases, after all, are brought against government entities such as housing authorities or police departments or, as was true of the “secret evidence” cases, the FBI.

That review appointment made two things clear. First, as an Arab-American who now had an intimate understanding of the complex legal and operational issues surrounding our national security, I could act as a bridge between groups such as the Arab American Institute and the American Muslim Political Action Committee and the government. The Arab-American community was starting to organize, and they sought increased access to government officials to press their agenda on a variety of topics, including Middle East peace, civil rights, and hate crime legislation. While I did not professionally identify as Arab-American, nor did I work with or for the political groups clamoring for recognition, I had the right heritage and the right credentials for this role.

Second, I was becoming a “terrorism expert.” As my work drew me deeper into the national security apparatus, I became privy to information about the threats to our nation from various terrorist organizations thriving abroad and at home, as well as about the amount of activity—surveillance, intelligence operations, military actions, law enforcement raids—being performed to protect the country.

At first, it was hard for me to reconcile these new roles with the career trajectory I had once imagined. I’d spent hours in law school defending prisoners in administrative hearings against corrections officers. I’d spent the summer after my first year in law school in Montgomery, Alabama, working on death penalty appeals for lawyer and Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption author Bryan Stevenson. I boarded at the home of Virginia Durr, the white activist who helped bail out Rosa Parks after she was arrested on that bus in 1955. Indeed, the first time I encountered anything related to terrorism was outside the office. The “Unabomber,” Ted Kaczynski, had added my scientist brother, Jon Faiz Kayyem, to a list of potential targets, and, after Kaczynski’s arrest in 1996, the government wanted to make sure there were no unopened boxes around his house.

I was not born to be a terrorism expert. I simply morphed into one, in stages.

Stage One: Admission. Literally.

I applied for and was eventually granted top-secret security clearance. This wasn’t a test of academic prowess or firearms acumen or language skills. It was a lot of forms—a series of questions to be answered under penalty of perjury. Some of these were tedious: I had to list all places of residence for the last fifteen years. Others were simply silly: I had to swear that I had never supported the Communist Party or advocated the downfall of the United States.

Only one made me groan, and then laugh: I had to list my foreign-born relatives. My mother, born Milly Deeb, has eight brothers and sisters. As I wrote down the birthplaces of my aunts and uncles, I traced my family’s path to America:

Eddie

Kooba, Lebanon (in the Batroun District)

Alice

Havana, Cuba

Libby

Kooba, Lebanon

Carrie

Kooba, Lebanon

Milly (my mother)

Kooba, Lebanon

Rosie

Kentucky, United States

George

Kentucky, United States

Janice

Kentucky, United States

Georgette

Kentucky, United States

This list still cracks me up. It looks so nefarious without context. I imagined a distraught FBI agent reading my clearance papers, trying to piece together the strange journey that led my family from Lebanon to Cuba, back again to Lebanon, and finally to Kentucky.

I was asked, predictably, for more information. So began a seemingly endless back-and-forth about my family’s exodus so many decades ago. The men and women charged with granting security clearance needed proof of my statements on the form. So I obliged: old passports, documents, aged papers from decades past, notarized written statements when nothing else could be found. Even when I thought I was done, I received requests for more proof: travel logs, social security numbers, records of foreign business interests, marriage certificates, and driver’s licenses. And once wasn’t enough. Security clearances are regularly updated, and as I rose in the government over the years, the reviews became more rigorous—proof, more proof, and even more proof.

My mother’s mother, Rose—or, as I called her, Situ, which means “grandmother” in some dialects of Arabic—and my grandfather were young and poor when they left Lebanon for the first time in 1929. They traveled to Cuba, hoping to make their way to America after two previous attempts had been thwarted. Before Castro assumed power, Cuba promised easy access to America for immigrants in search of a better life. Notices in newspapers throughout the developing world lured adventure seekers to Cuban shores, advertising a pit stop on the way to the Promised Land. It turned out this was a ruse; access to the United States was no easier from Cuba than it was from Lebanon. My grandparents stayed in Havana long enough for my grandmother to give birth to their second child. Older now but still poor, and with no family in Cuba, they returned to Lebanon in 1932. They would stay there long enough to welcome three more children, including my mother.

My mother was their last child born in Kooba, a small mountain village where neighbors greeted guests for tea with a selection of fresh mints and a range of cigarette boxes. Their house was the size of a few parking spaces. (In fact, when I visited years later, it actually had been demolished to build two parking spaces.) When my mother was just one, the family accomplished from Lebanon what they couldn’t from Cuba and, with papers in hand, arrived at Ellis Island.

Or at least, this is what I thought for most of my life. The myths immigrant families create to explain their journeys to new lands cannot be easily verified. My mother and her family had always told one story, which culminated in their arrival on the great island that had welcomed so many before them. Had we scrutinized further, we would have noticed that Situ’s documents showed a different route through the port of New York. The ruse was discovered not by the enterprising FBI agent who pored over my clearance papers but by a curious uncle fascinated with the family tree.

Here’s the kicker: Situ lived a long time, and she must have known that we were all perpetuating the Ellis Island lie. Her journey from Lebanon to Cuba to America was a source of great pride. She had overcome countless obstacles to bring her family here. My grandparents belonged to a generation of immigrants that became Americans, and their supposed arrival on Ellis Island was an important signifier of that new identity. So I can understand why she might not have been inclined to correct this mistake. It also made for a great story.

I know, for a fact, that the next part of that great story is true: The Deebs settled in Kentucky, where the weather was appealing. Kentucky is horse country, which must have felt familiar to so many Arabs who raised and groomed these animals before arriving in America. The Deebs did not last long in Kentucky—nor did my grandparents’ marriage. I can only imagine how bad their relationship became, for Situ willingly divorced my grandfather and raised nine children on her own. No one speaks of Eli, my grandfather. I have never seen a picture of him. He holds no place in my head or my heart, and years later, when David and I proposed to name our second son Eli because we liked the name, I was surprised when my mother looked at me fiercely and said “You will not name him that.” I had forgotten about my grandfather. We were taught to look forward, not back.

Like so many others, the Deebs went west. Situ had had her first child at age fourteen; the age difference between her and her eldest son, Edward, was ten years less than the age difference between her eldest and her youngest child. She is remembered by more than one hundred children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren. (“Juliette who?” I am sometimes asked when I attend a crowded family event in Los Angeles. “Oh, you’re Milly’s youngest.”)

There is, of course, another side to my family: the Kayyems. I was also required to produce proof of their journey to America. My paternal grandfather, Faiz, was born in Lebanon (or possibly some part of Syria), and married my grandmother, also named Rose, a much younger beauty. The exact nature of his business varied; he was in textiles from Japan, silk from China, real estate in Hawaii. He was, by all accounts, successful, if not impatient. He moved his family into nine different rental homes, requiring my dad to attend eight different schools by the time he graduated high school. My dad was raised in Hawaii and California, where he would eventually meet my mother. My parents may have come from the same corner of the world, but they were raised under very different circumstances.

Strict and domineering, Faiz roused a rebellious spirit in my dad that has animated him for his entire life. Consider, as I did while filling out those forms, the notorious story of my father’s arrest. As a college student, he was once accused of robbery and assault on a policeman. The charge was unsubstantiated and soon dismissed after he was held for two days—it turns out my dad had lost his wallet close to the scene of the crime. But this episode engendered a lasting habit among all Kayyems: we are skeptical of first reports (in my dark-haired dad’s case, the assailant was described as “redheaded”), a legacy that has served me well throughout my career. My father’s childhood boasted other incidents that proved of little interest with regard to my security clearance, thankfully. There were fistfights in Catholic schools; more than one near-death experience in the ocean around Hawaii; and pictures of him from the 1970s with a moustache, large collars, and cigarettes (before he and my mother embraced the healthy lifestyle that makes them very youthful seventy-plus-year-olds today). Simply put, my dad knew how to have fun, in his own way. One time, as an experiment, my dad tried to fit my older brother, Jon Faiz; my sister, Marisa; and me on his Harley Davidson for a ride around West Los Angeles. The experiment worked, but then he had to face my mother.

As I finished the last question on those painfully long forms, I was actually thankful for the opportunity to retrace my family’s journeys. It was a way to acknowledge how the Kayyem and Deeb histories have shaped my professional beliefs. My ancestors lived in a country with a long and painful legacy of civil war, and I grew up listening to stories that taught me people are more resilient than we might expect. My opposition to the 2003 Iraq War grew from my knowledge of Lebanon’s sad history of occupation. I spent many dinners with Arabs who could have told the war’s planners not to expect roses in the streets of Baghdad, and I listened. I support comprehensive immigration reform because I recognize how this nation thrives when it welcomes those who wish to immigrate. Not so long ago, my family chose this country as their home. I have seen the statistics and I believe profiling is ineffective at best, unlawful at worst. I have also seen how many people are profiled—like my brother, Jon Faiz, when he is unshaven. I take issue with the NYPD’s nicely named “Demographics Unit,” which targeted Muslim and Arab communities. It was an unsuccessful program. I knew it would be, because I know—from Situ’s experience—that America’s greatest strength is its acceptance of all religions and creeds.

When I turned in my completed forms, I sat down with the FBI agent to discuss my security clearance. He had already interviewed my friends, neighbors, and family, who had doubly validated my claims. The agent congratulated me. “Welcome to the club,” he said.

It didn’t feel like true acceptance—more like my proof had held up, for now. The vagaries of my security clearance review, the journey it unearthed, meant that I would always feel that I had one foot firmly in the security world, but that the other lingered behind, tethered to my history, my background, my identity, my family, my home. I didn’t know it then, but I would spend the rest of my career trying to become someone who could fit into all these worlds: the daughter of an immigrant family, an East Coast transplant from California, a young bride to her college sweetheart, a public servant, a security expert, and, eventually, a mother.

Product Details

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster (April 25, 2017)

- Length: 272 pages

- ISBN13: 9781476733753

Browse Related Books

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Security Mom Trade Paperback 9781476733753

- Author Photo (jpg): Juliette Kayyem Doug Weisman Photography(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit