Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

Table of Contents

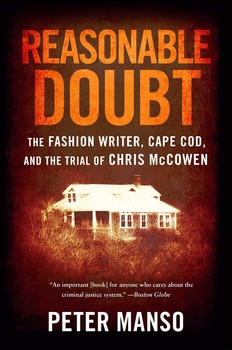

About The Book

In January 2002, forty-six-year-old Christa Worthington was found stabbed to death in the kitchen of her Cape Cod cottage, her curly-haired toddler clutching her body. A former Vassar girl and scion of a prominent local family, Christa had abandoned a glamorous career as a fashion writer for a simpler life on the Cape, where she had an affair with a married fisherman and had his child. After her murder, evidence pointed toward several local men who had known her.

Yet in 2005, investigators arrested Christopher McCowen, a thirty-four-year-old African-American garbage collector with an IQ of 76. The local headlines screamed, “Black Trash Hauler Ruins Beautiful White Family” and “Black Murderer Apprehended in Fashion Writer Slaying,” while the sole evidence against McCowen was a DNA match showing that he’d had sex with Worthington prior to her murder.

There were no fingerprints, no witnesses, and although the state medical examiner acknowledged there was no evidence of rape, after a five-week trial— replete with conflicting testimony and accusations of crime scene contamination— McCowen was condemned to three lifetime sentences with no parole.

Rarely has a homicide trial been refracted so clearly through the prism of those who engineered it. Bestselling author and biographer Peter Manso dug deep into the case, and the results were explosive. The Cape DA indicted the author, threatening him with fifty years in prison. In this exhaustively researched and vividly accessible book, Manso bares the anatomy of a horrific murder, a botched investigation rife with bias, and one of the most grossly unjust verdicts in modern trial history. “Only the fearless and risk-taking Peter Manso—capitalizing on his unique familiarity with the culture of the Cape and its denizens, including the victim of this horrible killing—could have written this powerful expose of prosecutorial corruption and the conviction of a possibly innocent victim of racial stereotyping. It will shock, enrage and educate you” (Alan Dershowitz, author of Taking the Stand and Reversal of Fortune).

Excerpt

Like any other bleak winter day, Sunday, January 6, 2002, was gray and windy, the metallic smell of rain heavy in the air. Cape Cod knows only three colors in winter: gray, darker gray, and the muted green of omnipresent scrub pines, somber hues that only add to the depression that engulfs many locals during this phase of the year. As Henry David Thoreau once observed, “It is a wild place, and there is no flattery in it.”

Just outside the kitchen of the bungalow at 50 Depot Road, Christa Worthington’s green Ford Escort was parked, as usual, at the top of her long driveway. A plastic Little Tikes car belonging to her daughter, Ava, was not far away, waiting to be used once more come spring. The telltales were barely noticeable at first glance: on the flag-stone walkway curving back to the house lay a barrette, also a pair of eyeglasses near the Escort’s driver’s door. Under the front tire was a wool sock, its mate several feet away in a flower bed. Farther away still, south toward the woods, a set of keys lay on the ground on the Escort’s passenger side, as if someone had flung them from the house.

Inside, the home seemed too small for its contents. What was always known as the “back door” led into the kitchen, which was Cape Cod tiny, a mere 120 square feet, not accounting for the appliances, the free-standing cabinet just behind the door, and the counters. The table was covered with newspapers, old mail, flyers, and notes. Toys scattered across the floor made the room even smaller.

Dirty dishes overflowed in the sink. Food-encrusted pans covered the burners of the galley-style stove opposite the doorway. At the right rear corner, the room opened into a narrow hallway that led to the living room. Along the right side of the hallway, on the easterly side of the house, were two doors: one led to Christa’s study, the other to the bathroom. In the study, a lone desk lamp illuminated a room nearly as cramped as the kitchen and just as messy, with a floor-to-ceiling stack of cardboard file boxes, plastic bins, a desk and chair, piles of magazines, and more loose paperwork. A Dell laptop computer, its screen still glowing, reported that the last user had logged off the Internet.

In the northwest corner of the house, the living room offered a “million-dollar” view of the salt marsh leading down to Pamet Harbor, then the bay and Provincetown, with the Pilgrim Monument in the distance. Paintings by Christa’s mother, Gloria Worthington, covered the walls. Two couches, a coffee table, a Christmas tree, and Christa’s childhood piano made this space cramped, too. The couches were littered with coats and books. On the far side of the living room, the north end, the so-called front door was locked. It had not been used in years, the kitchen entry being closer to the driveway turnaround where occupants always parked. The door to the bedroom, kitty-corner to the locked front entry, was shut, too. More toys strewn across the floor made the living room hard to navigate.

The little girl who owned the toys, barely two and a half, managed the transit with no problem. She had turned on the television to play her favorite video but hadn’t been able to figure out how to get the VCR tape into the machine. She’d put it in end first, then tried it sideways, then upside down. She soon stopped, wondering when her mother was going to wake up.

Despite the mess, the house appeared to be in its natural state, unaffected by the force of a struggle. The only aberration lay on the floor in the hallway: a woman’s body, naked from the chest down. Her head leaned toward her right shoulder, and blood had pooled on the floor below her swollen mouth. On her bare stomach were tiny red handprints.

The little girl made her way back toward the kitchen, stopping to tug at her mother again. She was hungry and equally starved for attention. She had never gone this long without talking to an adult. Most of all, she missed her mother’s smile, her cooing sounds. Earlier, she had tried to clean her mother as her mother had so often cleaned her, using a hand mitt to wipe up the blood.

In the kitchen, she poured herself a bowl of Cheerios, a skill she’d recently acquired. She added milk to the bowl, barely noticing the bloodstains she left on the glass bottle of organic milk her mother always bought. Her hands were covered with blood. It was under her fingernails and in her hair. She ate a little but did not finish. Her attention wandered again.

The late-afternoon sun began to set. The day had almost passed, and her mother still had not gotten up. She grabbed a bottle of apple juice from the refrigerator and put it down next to her mother, then curled up beside her on the floor. Her mother had said she would have to stop nursing soon, but for the moment, she gave up on the juice for the familiarity of her mother’s nipple.

Most eyes in Massachusetts that Sunday were on the New England Patriots, winners of five straight games and closing out a Cinderella season. The Patriots needed a victory to clinch the AFC East division title and a loss by the Oakland Raiders to seal an improbable bye in the first round of the playoffs. The victory was almost a certainty, their opponents being the Carolina Panthers, a team in the midst of a fourteen-game losing streak. Still, New England was leading just 10–3 at halftime when Robert Arnold, in his late seventies, went to pick up his son, Tim, age forty-four, in Wellfleet.

Since his brain surgery seven months earlier, Tim suffered double vision and balance and coordination problems, and he couldn’t drive. He normally lived with his parents, but since mid-November, he’d been house-sitting for friends in Wellfleet. His father was picking him up so Tim could do his laundry at home.

By the third quarter of the game, the clothes were in the dryer and the Patriots had jumped ahead 24–6. Tim decided to call Christa Worthington, an ex-lover who remained a friend, to see if she still wanted to go out for Sunday night dinner. He had suggested Saturday, but she had said no. Tim had gotten the impression she was going off-Cape to see her dad. When she didn’t answer, he thought she might still be away. He left a message on her answering machine and went back to the game.

A half hour later, with New England up 38-6 and running out the clock, Robert Arnold was ready to drive the six miles back to Well-fleet. Noticing a flashlight Tim had borrowed from Christa, he suggested they return it on the way. Robert grabbed the flashlight, Tim picked up the laundry basket, and they got into Robert’s seven-year-old Ford Windstar.

As Robert drove around Old County Road and then cut back up Depot, Tim wondered whether he should return the flashlight unannounced. Christa had chastised him before for showing up without calling, and although he’d left her a message, she hadn’t given him the OK to come by. Seeing her always stirred emotions. Just two months earlier, he had written in his journal: “There is such an ache where she and Ava used to be. The first Father’s Day gift she gave me was a picture of Ava in my arms. Ouch. That hurts badly. Especially now that I can look back and see how little she was involved.”

Often, he’d tried to convince himself that he had the upper hand, writing in his diary that she could be “impatient, angry, hostile, unpleasant,” and that he had “left her several times because she was so difficult, so cutting, so caustic, on the attack.” But he couldn’t give up the idea of the two of them together.

He decided it would be best just to leave the flashlight on her back porch.

As they slowed to take the left into Christa’s driveway, it was Robert who first saw two copies of the New York Times in familiar blue plastic wrappers. Tim got out and grabbed the papers. They drove up the 175-foot drive, a narrow dirt road topped with weeds and crushed clam-shells. As it curved to the left near the house, Tim was surprised to see Christa’s car. He also noticed the light on in her study. It was dusk.

He got out, flashlight and newspapers in hand, crossed the flag-stone walkway, and went up the three steps to the kitchen landing. The rickety wooden storm door was closed. The inside door stood open more than halfway. Looking inside, as he later recalled, he immediately saw Christa on the floor with Ava. The child appeared to be breast-feeding. He thought it an odd place to nurse, then remembered that Christa would often stop whatever she was doing to give Ava her breast, no matter where.

When he called out, Ava’s head popped up. The little girl ran to him as he stepped into the kitchen, putting the newspapers down. Ava was a talkative child, but at this moment, she said nothing, only clung to him. He took the three or four steps across the kitchen with her in his arms and looked down at Christa. She was naked from the chest down, a bathrobe and black fleece shirt around her shoulders. Her legs were splayed. Her right knee was bent, pointing at the ceiling. Her left leg was bent at the knee, too, but entirely flat on the ground.

Tim blinked, having trouble with what he was seeing. Her lips were horribly swollen, as if she had been hit, and much blood had run down the side of her face onto the floor. Some of it was still wet, glistening. Her eyes were wide open, staring at the ceiling, unfocused. He looked into her eyes, and all he saw was white. In a daze, he reached down and touched her cheek. It was cold. Panic rushed through him. He looked for the phone, a cordless model that should have been on its cradle on the wall but wasn’t.

With Ava still in his arms, he stepped over the body and into the living room. The television was on, a children’s show. The flashlight was still in his hand, and he put it down on a windowsill to turn the TV off, then stepped back over the body and reached down to check Christa’s pulse. Nothing. The open bathroom door was just beyond her head. Inside, he saw blood on the rim of the sink and a red-stained wash mitt on the floor underneath. Ava’s little step stool was there, too. The child, he realized, had tried to clean her bloodied mother. He forced himself to whisper comforting words to Ava as she clutched him.

He looked around the kitchen once more, remembering that the inside door had been open. Christa must have just gotten home. What could have happened so quickly?

He carried Ava out to the Windstar. His father had already turned the van around, so that it pointed downhill, back toward the road. As Tim climbed inside, he said, spelling for the sake of the child, “Christa is D-E-A-D,” his voice shaky. They sat in stunned silence, the only sound the whirr of the vehicle’s heater. Then Tim said, “I can’t find a phone anywhere.”

Robert left the Windstar to go inside. As he later testified in court, first he could bear only a quick glance at the body as he looked around the kitchen, putting his hand against the wall to steady himself. He had never been in Christa’s house before and wasn’t sure where to look. The place was cluttered. He looked at Christa again. He was a retired veterinarian; he’d seen death before but not like this. The right side of the young woman’s face had been beaten, contusions covering her upper lip, nose, and forehead, and smeared streaks of blood laced her chest and abdomen. Her lips were swollen but pulled back, exposing her teeth, gleaming reddish from the blood she’d aspirated.

He stepped over the body to check the living room. No phone. Quickly, he returned to the Windstar.

They sat in the van in silence again, both rattled, having trouble deciding what to do. After a moment, Tim passed Ava to his father and went back inside. Again, he checked the kitchen, the living room; he opened the bedroom door and took a quick look, remembering other times when Christa’s phone was difficult to find, a cordless in a cluttered house. He turned around for the second time, deciding that the only recourse was to go back up the path to his father’s house to call from there. He left the house without noticing Christa’s cell phone on the kitchen table. It was on, the illuminated screen revealing a lone 9.

As in 911.

He ran up the 100-yard path to his father’s house, then dialed the police emergency number. It was just before 4:30 P.M. In a surprisingly coherent voice, he told the dispatcher he thought Christa Worthington had fallen down her stairs. The Truro police switchboard logs report him saying, “I think she is dead.”

Robert continued to wait in the minivan, holding Ava, who rested her head against his neck. Although he never talked about it later, he had to have smelled both Christa’s blood and Ava’s dirty diaper.

Meanwhile, Christa’s cousin Jan Worthington, a member of Truro’s rescue squad, was reading the newspaper at her North Pamet Road home two miles away when her pager went off. The dispatcher announced: “You have a rescue call—50 Depot Road, the Worthington residence—for an unconscious, unresponsive female.”

Jan thought of her mother, Cindy, who had a pacemaker. The address was wrong, but errors like that were made all the time. She drove as fast as she could, slowing only when she pulled abreast of her parents’ house on the opposite side of Depot from Christa’s, several hundred yards west. No cars, no activity.

She turned back to Christa’s driveway. At the top of the hill, she saw Tim Arnold standing next to his father’s minivan.

“It’s Christa. I think she’s dead.”

She ran up the steps and stopped at the landing. Through the kitchen door, Jan saw Christa on her back, wearing what appeared to be a green bathrobe bunched up around her shoulders. Her legs were in a weird position, “akimbo,” as Jan later described them. She turned back to Tim, screaming for an explanation. He repeated that maybe Christa had hit her head and fallen. But he didn’t know.

She again yelled at Tim, telling him to call the police. He said he couldn’t find the phone, forgetting that he had already called 911. Jan panicked and ran down the driveway, screaming, “Call the police! Somebody—call the police!” Halfway down the drive, she met the ambulance that had just returned from Hyannis and was minutes away when the emergency call for 50 Depot Road came in. Paramedic Jeff Francis, responding from his nearby home, followed in his car. All of them later recalled Jan’s shrieks.

Francis was the first official responder to step inside. The ambulance crew followed, one carrying the “first-in bag,” three others bringing the defibrillator and oxygen. They flipped the light switch near the kitchen table, and Francis noticed a pool of blood about eight inches by fourteen inches around Christa’s head. He bent to feel the pulse on her neck.

“Code ninety-nine!”

The patient was not breathing. He instructed the crew to clear an area so they could move the body. They slammed the open portable dishwasher shut, slid it back to create space, and began moving toys away from Christa’s feet. The body had stiffened in its awkward position. “Code thirteen,” Francis reported on his radio, meaning that rigor had set in. They gave up on moving her.

Two members of the ambulance crew later recalled seeing the sea-green bathrobe around Christa’s shoulders and two bloody handprints on the flat of her stomach. Fecal matter was under her and between her legs, blood behind her ear. They used a brown blanket from the couch to cover her body. A plastic yellow disposable blanket from the ambulance was also put on top of the body.

The deputy fire chief and two emergency medical technicians had arrived. The kitchen was getting crowded. Outside, a second ambulance pulled up, then a Truro police lieutenant and the Truro fire captain. Cars and trucks were parked end-to-end along the narrow driveway, and Jan was still screaming. She stopped only with the arrival of her father, on foot, from across the road. The ambulance crew searched the house, looking for the baby, whose toys and handprints were everywhere.

Outside, Tim Arnold explained that Ava was safe in the Windstar with his father. Someone brought out a supply of diapers, and EMT George Malloy carried the little girl down the driveway to Jan’s parents’ home. Malloy would state that the child, whom he held in his arms for the next hour, “never once stopped shaking.”

He added, “Anybody who says she didn’t see what happened up there is totally crazy.”

Later that evening, the long probe into Christa Worthington’s murder began.

© 2011 Peter Manso

Product Details

- Publisher: Atria Books (December 19, 2017)

- Length: 464 pages

- ISBN13: 9780743296687

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

“The Christa Worthington murder case on [old] Cape Cod is an unusually captivating story, and Peter Manso has expertly plumbed the depths of it to write a riveting book that true crime fans will love.” —Vincent Bugliosi, New York Times bestselling author of HELTER SKELTER and Outrage

"Only the fearless and risk-taking Peter Manso—capitalizing on his unique familiarity with the culture of the Cape and its denizens, including the victim of this horrible killing—could have written this powerful expose of prosecutorial corruption and the conviction of a possibly innocent victim of racial stereotyping. It will shock, enrage and educate you." —Alan Dershowitz, New York Times bestselling author of The Trials of Zion

"Manso is a fearless enemy of hyprocrisy, a great investigative reporter. Power brokers and officials who feed off their own inflated sense of self-importance have no greater foe. If every community in America had a Peter Manso there'd be no place for the bad guys to hide." —Morton Dean, former anchor, CBS Nightly News

"This is the dark side of the Cape that whispers in bad dreams, screams down the alley ... and hides out of sight on sunny days when tourists wonder the quaint old streets or lie on the sand in bliss." —Jeremy Larner, Academy Award winner for Best Original Screenplay for The Candidate

"Sex, courtroom drama, racism, social class, justice denied, a police procedural entwined in an exciting, well-written, true story. Don't start reading in the evening unless you're up for a sleepless night." —Nicholas Von Hoffman, columnist, New York Observer, and author of Radical: A Portrait of Saul Alinsky

"Peter Manso's account of the police and prosecutorial misconduct occurring in one case represents widespread practices that send thousands of black, Hispanic, Native American and poor whites to American prisons each day. His investigation...invited retaliation from a system that often treats its critics in the same way it treats its victims." —Ishmael Reed, author of Juice

“A keen observer and a talented writer…some of the courtroom scenes are riveting. Manso should be commended for taking up the cause of a long-forgotten man, whose trial raised serious questions about the strength of the State Police’s case and the fairness of the trial…An important [book] for anyone who cares about the criminal justice system.” —Boston Globe

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Reasonable Doubt Trade Paperback 9780743296687

- Author Photo (jpg): Peter Manso Courtesy Provincetown Banner(1.4 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit