Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

Table of Contents

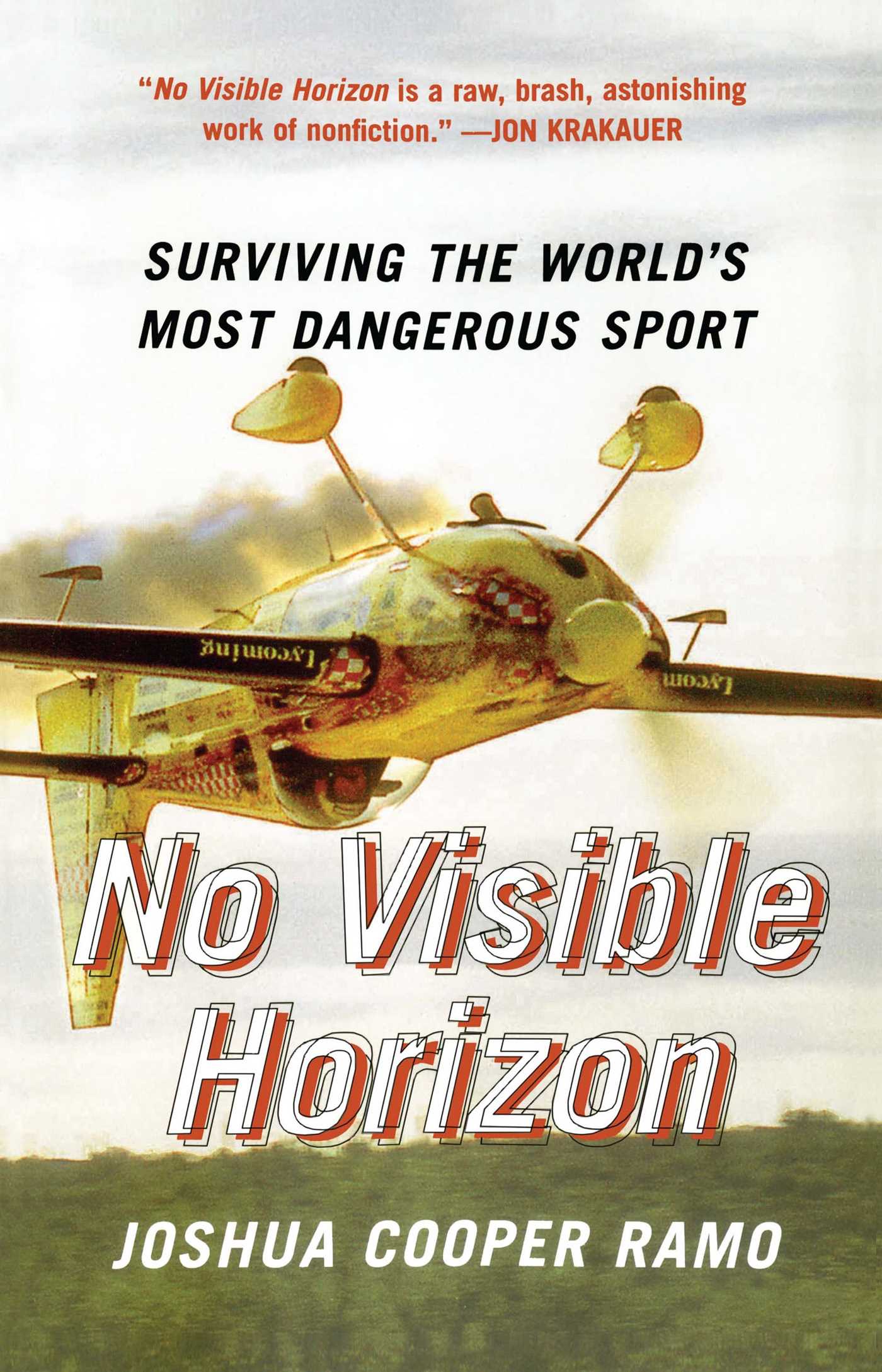

About The Book

Excerpt

In the middle of the fifteenth century in Japan, a time when the kingdom was both at its most isolated and, to Japanese eyes, most perfect, a strange tradition emerged: composing haiku as you died, at the very moment of death. Perhaps it wasn't so surprising. Japanese culture had become obsessed with the relationship between life and art. There was an increasing belief that the two should never be separated, that a well-lived life was a work of art. Was it surprising that some Japanese poets wanted to try to weave the two together, to make a little tatami of life and art? What better time than at the moment of death? After a lifetime of study, could you be beautiful in three lines? Could you be perfect? Could you reduce it, all of it, your life, down to seventeen syllables?

Mame de iyo

mi wa narawashi no

kusa no tsuyu

Farewell...I

pass as all things do

dew on the grass.

So it all awaited you. Special inks were mixed. A brush of the rarest hair was prepared and left lying near your bed. The softest rice paper was fetched. All this lay waiting for your last moment. The Zen monks who collected the death poems looked for two virtues, two marks of beauty. The first was awa-re, a sense of the sadness of things passing, the way birds at dawn sing like mourners or cherry blossoms fall like tears in the spring. The second virtue was mi-yabi, an attempt to refine oneself. Everything about the poems -- their sound, how they looked on the page -- was meant to evoke this attempt at refinement, at compactness. So Basho, dead in early June 1807:

Tabi ni yande

yume wa kareno o

kakemeguru

On a journey, ill:

my dream goes wandering

over withered fields.

Or Cibuko, in the winter of 1788:

Yuku mizu to

tomo ni suzushiku

ishi kawa ya

The running stream

is cool...the pebbles

underfoot.

And, perfectly, Ozui, dead in January 1783:

Yo no hazuna

Heirkiru ware mo

Katachi nashi

Still tied to this world

I cool off and lose

my form.

It is the kind of day to write poems about. The summer sky bleeds from soft robin's-egg blue at the horizon to deepest azure directly above. In between are a million more shades, as if God, restless and unsatisfied, has unloaded the full spectrum into the heavens. A few clouds hover harmlessly in the breezeless sky, pulling weak shadows over the earth. It is a day to fall in love, to lie on the grass and listen to Louis Armstrong.

I am flying at the height of those clouds, 1,000 feet, and fast out of a dive: 200 miles an hour. To amuse myself I roll upside down and pass just above the clouds, dragging my tail in the vapor that steams upward from each, watching the reflection of my yellow plane. I pump the stick slightly to bump the nose up. The Extra 200, a German-built plane, is made for these aerial acrobatics the way a Porsche is made for the autobahn. I jam the stick to the left side of the cockpit, drawing the left wing ailerons up into the airstream, where they bite into the airflow and quickly pull the wing up and around, right side up, then inverted again. The Extra can come full around in less than a second, faster than you can say "roll." My shoulder and crotch belts dig into my skin as I float upside down. The steel ratchets that hold them tight grind at my hips. I stop the plane hard, exactly wings level and inverted. Sweat runs up from my chin and into my eyes.

I am going to pull through from here toward the ocean below me. Hold your hand out, palm up. Flip it over. Now arc it away from you and down. A split-S maneuver, de rigueur in competition aerobatics, the sport of precision flying. I fuss with the power a bit. I press the nose up for a second to make sure I am level. I glance out over the wing, squinting. Is it aligned with the horizon? As I set up I notice everything: the shudder and whir of the propeller, the twitch of my rudder in the slipstream, the stink of gasoline draining from the tank. What I don't notice is that I am cluelessly, stealthily losing altitude. I check and recheck my alignment, inverted for a good twenty seconds, ignoring my altimeter as it shows me leaching height. I am descending, unawares. I am about to start a maneuver that takes 800 feet from an altitude of 700 feet.

"Pssshhh." I pop the air out of my lungs and suck in a new breath as I start the pull. Almost immediately, my eyes begin to gray out as the blood rushes from my head. The g-meter creeps past seven. In the cockpit now I weigh seven times my weight, more than 1,000 pounds. I lose sight of the horizon and then my vision squeezes into a tunnel, as if I were peering through a paper-towel holder. I tuck my chin to my chest and close the back of my throat. I suck in on my abdominal muscles, trying to trap blood in my head and heart. I grunt, a hum of pain and stability. I am like a locked-in coma patient. My mind is alive in this useless hunk of a body. It is wonderful.

And then, in an instant no longer than it takes my brain to assemble a single neuron, I am terrified. I have seen from the angle of the sun and the sea below that I am too low. I can't tell how much I am off, but I know that even a foot is too much. Friends have died this way. "Aaargh." The breath shoots out of me in a horrified burst. In an instant my mind is cranking through the options. I don't have enough room to pull the maneuver through without putting more stress on the plane than it can handle, snapping the wings off. But I am too far along to roll the plane back upright. My options flip in front of me, shuffling cards, all bad. And then the thought comes to me, the one everyone always asks about. "If something happens up there, what will you think? Will you think the risks you took were worth the way your life ended? Will you be sad? Will you think of your family?" Here, on the last day of my life, in the last moment, I am writing a death poem with my plane. Now, with the water coming up at me at more than 200 miles per hour, what am I feeling? What am I thinking? I don't feel remorse or fear of death or even of pain. I don't think about my family or the life I am about to slam into pieces. What I am feeling in that one moment of truth is anger. Deep, profound anger.

"Shit," I think. "I've just killed myself."

Copyright © 2003 by Joshua Cooper Ramo

Product Details

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster (April 8, 2004)

- Length: 288 pages

- ISBN13: 9780743257909

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

Jon Krakauer Joshua Cooper Ramo deftly conveys why he and a handful of kindred souls feel compelled to fly small airplanes right at the edge of what's possible, and sometimes beyond. The author is a risk-taker on the page as well as in the sky, and the rewards of this fine book are commensurate with the chances taken. Ramo's is an original voice to be sure, but in his inflections one can detect echoes of James Salter, Peter Matthiessen, Norman Maclean, and Antoine de Saint-Exupéry -- a resonance that reflects well on all parties.

Outside Magazine [Ramo's] a strong, reflective storyteller. Exploring what drives him to take ridiculous chances, he turns this book into an eminently readable meditation on humankind's craving for risk.

Time Magazine When he's in the cockpit performing feats of gritty derring-do (and occasionally derring-don't), his airplane groaning and shuddering with the strain, the book soars.

The Economist Ramo writes so well that it is infectious.

Colonel (Ret.) Frank Borman Ramo has the right stuff and so does his book. It's a classic.

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): No Visible Horizon Trade Paperback 9780743257909

- Author Photo (jpg): Joshua Cooper Ramo Photo Credit: Kim Jew(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit