Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

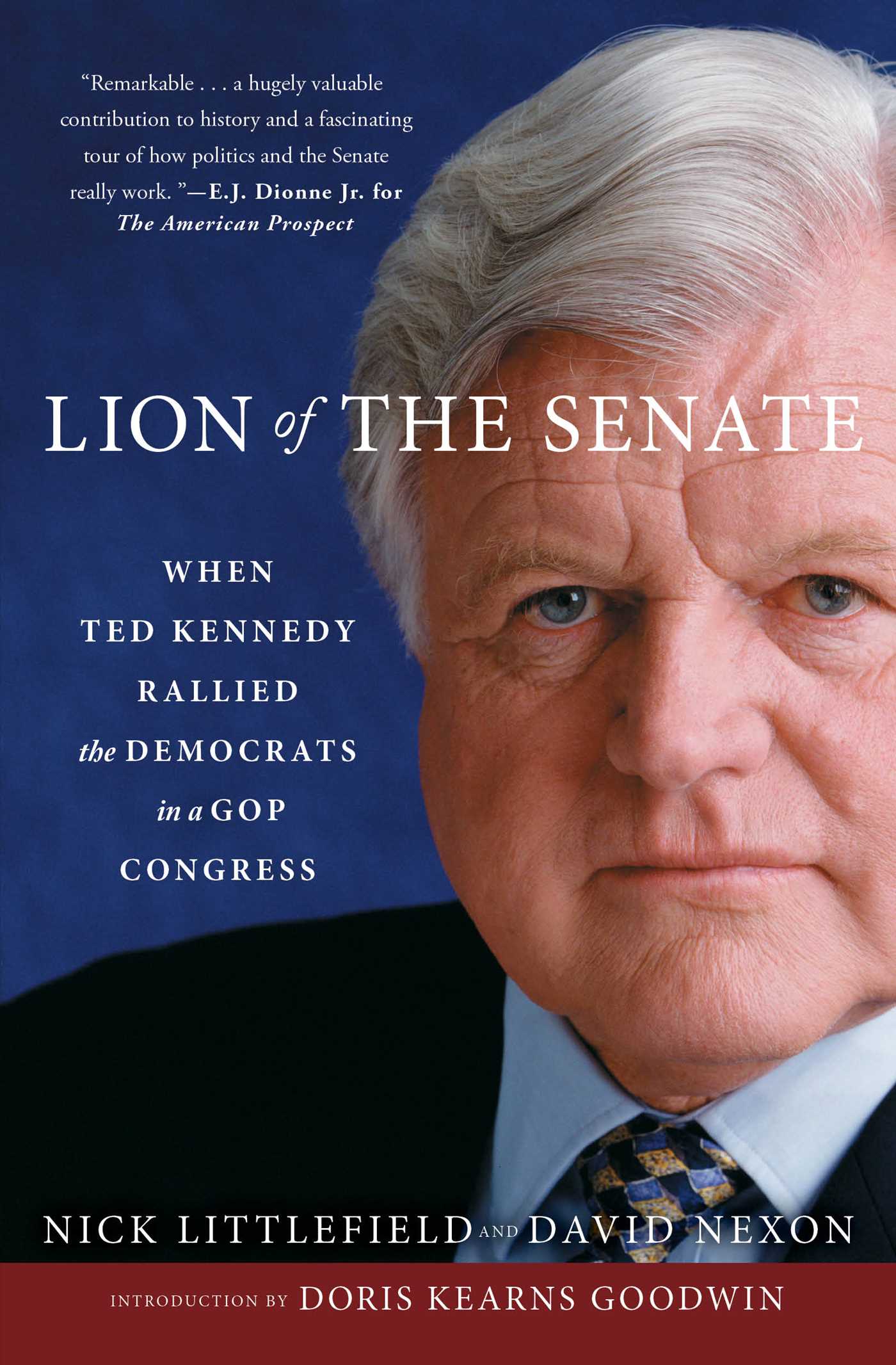

Lion of the Senate

When Ted Kennedy Rallied the Democrats in a GOP Congress

By Nick Littlefield and David Nexon

Table of Contents

About The Book

An insider’s look at the two years when Senator Ted Kennedy held at bay both Newt Gingrich and his Republican majority: “For those who love politics and care about policy—and those looking for an account of how Washington used to work, Lion of the Senate is pure catnip” (USA TODAY).

The November 1994 election swept a new breed of Republicans into control of the United States Congress. Led by Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich, the Republicans were determined to enact a radically conservative agenda that would reshape American government. Some wanted to shut down the government. If Gingrich’s “Contract with America” been enacted, they would have shredded the federal safety net, decimated the federal programs, and struck down the regulatory framework that protects health, safety, and the environment. And, were it not for Ted Kennedy, who had defeated Mitt Romney for his Senate seat in 1994, they would have succeeded.

In Lion of the Senate Nick Littlefield and David Nexon describe never-before-disclosed maneuvers of closed-door meetings in which Kennedy galvanized his party, including the two pivotal years, 1995 and 1996, when the Republicans held control of Congress and he fought to preserve the mission of the Democratic Party in the face of the right-wing onslaught. Here is the nitty-gritty of Kennedy’s role, and the details of a fascinating, bare-knuckled, and frequently hilarious fight in the United States Senate.

“Compelling…as a story about how the Senate operates—well, how the Senate used to operate—and a story about perhaps the greatest Senate lawmaker of the second half of the twentieth century, Lion of the Senate succeeds” (The Washington Post) as a political lesson for all time. With an introduction by Doris Kearns Goodwin, this is “a fine rendering that deserves a wide readership” (Kirkus Reviews).

The November 1994 election swept a new breed of Republicans into control of the United States Congress. Led by Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich, the Republicans were determined to enact a radically conservative agenda that would reshape American government. Some wanted to shut down the government. If Gingrich’s “Contract with America” been enacted, they would have shredded the federal safety net, decimated the federal programs, and struck down the regulatory framework that protects health, safety, and the environment. And, were it not for Ted Kennedy, who had defeated Mitt Romney for his Senate seat in 1994, they would have succeeded.

In Lion of the Senate Nick Littlefield and David Nexon describe never-before-disclosed maneuvers of closed-door meetings in which Kennedy galvanized his party, including the two pivotal years, 1995 and 1996, when the Republicans held control of Congress and he fought to preserve the mission of the Democratic Party in the face of the right-wing onslaught. Here is the nitty-gritty of Kennedy’s role, and the details of a fascinating, bare-knuckled, and frequently hilarious fight in the United States Senate.

“Compelling…as a story about how the Senate operates—well, how the Senate used to operate—and a story about perhaps the greatest Senate lawmaker of the second half of the twentieth century, Lion of the Senate succeeds” (The Washington Post) as a political lesson for all time. With an introduction by Doris Kearns Goodwin, this is “a fine rendering that deserves a wide readership” (Kirkus Reviews).

Excerpt

Lion of the Senate Chapter 1 ELECTION DAY GLOUCESTER

When the doors of the Veterans Memorial Elementary School in Gloucester, Massachusetts, opened to admit the first voters at 7:00 in the morning on Election Day 1994, I was standing outside the school holding a red, white, and blue “Kennedy for Senate” sign, “doing visibility,” as they call it in Massachusetts politics. I had taken two weeks off from my job working for Kennedy in Washington to volunteer on the campaign. It was his tradition that for the final weekend and until the polls closed on Election Day, everyone involved in the campaign would leave the Boston headquarters and spread out across the state to help in local cities and towns. I chose to work in Gloucester, an hour north of Boston. Over the long hours in the early morning New England chill, holding my sign and saying “Good morning” to voters, I thought about what had brought me, a fifty-two-year-old lawyer and father of three, to this school and this moment.

I’d grown up in Providence, Rhode Island, and gone to Harvard College. My first job after college was as a Broadway singer in My Fair Lady in summer stock and in Kismet with Alfred Drake at Lincoln Center in New York. After one year in the professional theater I left to go to law school. I thought law and musical theater were the opposite poles in my life, never imagining that singing would become a great political asset, especially when I worked for Kennedy.

When I was in law school at the University of Pennsylvania, part of a generation urged to go into public service by President John F. Kennedy, I worked on my first political campaign, for Governor John Chafee of Rhode Island, a progressive Republican. I drove Chafee around in a yellow and blue truck with speakers on the roof blasting a campaign ditty I’d written: “Keep the man you can trust in Rhode Island, with Chafee we’re moving along. Keep the man you can trust in Rhode Island, and keep Rhode Island strong.” Chafee won the election, and I finished law school. In 1968 he asked me to run his reelection campaign, which I did while studying for the New York Bar Exam. His defeat, due to his courageous support for a new state income tax, was my first political disappointment.

In 1970, while working at a New York law firm, I ran the “Lawyers Committee against the Vietnam War,” raising money for congressional antiwar candidates across the country. One of these candidates, the brilliant antiwar and civil rights activist Allard Lowenstein, recruited me to run a nationwide voter registration drive called Registration Summer the next year. A constitutional amendment lowering the voting age from twenty-one to eighteen had just passed, and we wanted to register young people, who we hoped would help stop the war with their votes. In 1972 I left my law firm and ran Al’s campaign to return to Congress. His loss was another profound disappointment; I was beginning to understand that losses are frequently part of politics and that losing hurts a great deal.

After the campaign the Republican U.S. attorney appointed me an assistant U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York (Manhattan and the Bronx). There I prosecuted corrupt politicians, drug dealers who were part of the infamous “French connection,” tax swindlers, and worked on white-collar and organized crime cases. I conducted over two dozen trials and learned how to make a convincing argument in front of a Manhattan jury, a formidable task for a Bostonian. When my four-year term ended I wanted to go home to New England to reconnect with my family and lifetime friends, so I accepted a job as a lecturer at Harvard Law School. I soon was running Harvard’s trial advocacy program, which I did for twelve years; I also taught prosecution and investigations and started a course called “The Government Lawyer” to encourage students to work in government by showing them the excitement and responsibility involved.

In 1978 the Massachusetts legislature established a special commission to investigate corruption in the state’s public construction projects. Bill Ward, the president of Amherst College, was appointed head of the commission; on the recommendation of Harvard Professor Archibald Cox and Manhattan District Attorney Robert Morgenthau, whom he knew through Amherst, Ward asked me to become chief counsel and executive director. We wanted to excite public opinion about the costs of corruption, which had become a way of life in Massachusetts. We hoped to convince a reluctant legislature to rewrite the laws and fix the problems we would identify. We decided that presenting evidence of the widespread kickbacks that we uncovered was the best way of doing this. Because there were still afternoon papers as well as afternoon and evening news shows that had to be filled, we determined to try to hold full public hearings every morning, and revelations from these hearings became our signature “bribe a day before lunch.” Our eighteen months of public hearings were covered extensively in the media.

One of my favorite bribery cases was that of William Masiello, who ran a pizza parlor in Worcester and decided he could make more money if he opened an architectural firm. Masiello quickly got public work by paying off the Worcester County commissioners and persuading them that there should be a new courthouse in each town in Worcester County, which is why, to this day, that area has four virtually identical courthouses within a radius of fifty miles. Masiello eventually succeeded in winning bribery-greased contracts all over the state.

The Ward Commission served its purpose: the legislature passed criminal laws to strengthen public corruption prosecutions and reform the construction process from bid to completion. It also created a permanent Inspector General’s Office to continue our work.

When the Ward Commission ended in 1981, I was married and the father of three, so for financial reasons I had to think about going back to a law firm. I took a job at Foley, Hoag and Eliot and spent almost eight years there. In the fall of 1988 Gregory Craig, an old friend from the Lowenstein campaign, called to tell me he was leaving his job as foreign policy advisor for Senator Kennedy. He told me that it was a tradition in Kennedy’s office to find candidates to succeed you when you left, and he was calling to urge me to be his replacement.

The idea of working for Kennedy was very enticing, but I wasn’t sure foreign policy was the right fit for me. As I was hesitating about the job, Ranny Cooper, the senator’s chief of staff, called to tell me that there was also a vacancy coming up in domestic policy for staff director for the Senate Labor and Human Resources Committee, which Kennedy chaired. The Labor Committee had jurisdiction over health care, medical research, doctor training, people with disabilities, the Food and Drug Administration, and education, including higher education, student loans, and school reform. It also had jurisdiction over jobs and job training, wages, labor, civil rights in the workplace, and even the arts and children’s issues, such as Head Start and child care.

I wanted to go back to government, but not as a prosecutor. I had learned from prosecuting two cases in which we mistakenly arrested the wrong person that the truth could be elusive and the consequences of mistakes dire. Although the falsely convicted bank robber and the wrongly identified international drug dealer were ultimately released, I no longer wanted to take the chance of ruining a person’s life and spending my time passing judgment on whether what people had done was wrong or criminal. Building people up was more important to me. This was an opportunity to return to a whole different kind of government service, where the goal was no longer being the cop on the beat but using government to try to improve people’s lives. It was irresistible.

Ranny arranged for me to be interviewed for the Labor Committee job by Kennedy and his Boston chief of staff, Barbara Souliotis, in Boston. I met the senator in the restaurant of the Harvard Club at 4:00 p.m. on a Friday, just after he’d finished his steam bath treatment for his bad back. This was the first time I had met him. He came upstairs in his well-pressed blue suit and well shined black shoes (he later told me that Kennedys don’t wear brown), sat at the table, and turned on the famous Kennedy charm: loud, funny, and warm.

“I want you to come work with me,” he said. “This is what we’re going to do: health care, raising the minimum wage, fixing the schools, to start.”

As it was my habit to take notes in every meeting, I grabbed the only available paper—a cocktail napkin—and jotted down what he said: Health care, minimum wage, schools. I felt like accepting on the spot but refrained, instead telling him I would think about it. He said he would see me in Washington.

I flew down for more formal meetings with the staff of the Labor Committee and with Kennedy’s personal staff. The staff members were expert in their substantive areas. I was an expert in none, but I would learn, and I knew how to develop and run a campaign. A week later I went to see Kennedy in his office. He took me out onto the balcony, turned to glance up and down Constitution Avenue, over the Capitol, the Supreme Court, the Washington Monument, and, in the distance, the rows of graves in Arlington National Cemetery, where both his brothers were buried (and where he is now buried). Before I could say anything, he asked me when I could start. I said, “How soon do you need me?”

The answer was February 1989. One of the first things Kennedy told me was that nothing could get done in the Senate unless it was bipartisan. The notion of good and bad guys, which I had been focused on for twelve years, was useless; we had to seek out Senate colleagues, Republicans and Democrats, for everything we did. Kennedy had great respect for the other senators and worked hard to build relationships with those across the aisle. This would prove particularly difficult on health care reform, the cause that was so central to Kennedy and that would be an ongoing focus of my career.

Five extraordinary years later, campaigning in Gloucester, I thought over some of our successes: we had passed landmark legislation through the Labor Committee, including the Americans with Disabilities Act, the Civil Rights Act of 1991 (strengthening the laws against discrimination in the workplace on the grounds of race, religion, or gender), the Family and Medical Leave Act, the Ryan White AIDS CARE Act, and the Child Care and Development Block Grant. Nothing was as important to me as Kennedy’s reelection.

Gloucester was a good place to spend Election Day, a working-class city of thirty thousand with a proud history that had fallen on hard economic times. The median family income was $32,000, close to the national median of $31,278. I thought that many of the voters I saw that day and had talked to over a weekend of phoning and canvassing neighborhoods had probably benefited from the senator’s legislation.

What I’d heard from voters during my time in Gloucester and from the latest polls gave me confidence about the outcome of the election, though the campaign had been the toughest of Kennedy’s long career. First elected to the Senate in 1962 at the age of thirty, he’d been reelected five times but hadn’t had a serious challenge in at least twelve years, until Republicans fielded the impressive Mitt Romney against him.

KENNEDY DEFEATS ROMNEY

Romney was a fresh and promising new face in Massachusetts politics. He was forty-four, clean-cut, and handsome, with a photogenic family and a lot of money that he was willing to plow into the campaign. He’d come to Massachusetts from Michigan to attend Harvard Law and Business schools in 1971 and stayed to make a fortune in the private equity business.

Several factors were working against Kennedy in this race. The storied Kennedy political organization in Massachusetts was out of practice, the senator himself was older and heavier, and the rape trial of his nephew in Palm Beach three years before had taken a toll on his reputation. Across the country Republicans were united, well-financed, and on the offensive. Kennedy was one of their prime targets; they attacked his politics as obsolete and out of touch. Although Massachusetts is regarded as a reliably Democratic state, the voters had elected a Republican governor, William Weld, in 1990, and were preparing to reelect him in a landslide in 1994, on the same ballot as Kennedy. Polls in the spring had shown that only one third of Massachusetts voters thought Kennedy deserved reelection, and, equally ominous, even one third of Democrats thought it was time for a change.1

On the other hand, the senator had one new extraordinary asset: Victoria Reggie Kennedy, whom he had married on July 3, 1992. Vicki was everything he could want in a wife. Beyond being “the love of his life,” as he often said, she was politically very astute and as good as most of his advisors at thinking strategically. They loved talking politics, and she was a great sounding board for his ideas. Despite their busy schedules, they ate dinner together practically every night, most meals featuring a vigorous discussion of politics and policy. She quickly became very popular in Massachusetts and helped to bridge the gap between his public persona and who he was personally, as a father and a husband. People got to know him all over again with Vicki at his side.

The Romney challenge had a strong start partly because Kennedy was busy with obligations that kept him from campaigning. For most of 1994, he was required to remain in Washington, carrying out his senatorial duties, especially working on President Clinton’s universal health insurance bill, so Vicki pitched in as an eloquent surrogate campaigner. The Senate remained in session through August, when it was normally in recess for elections, and as chairman of the Labor Committee, he took the lead on many issues for Clinton. And before his sister-in-law Jackie Kennedy Onassis died in May of that year, he and Vicki had flown back and forth to New York all spring to visit her. Meanwhile Romney’s television advertisements ran throughout the summer without a Kennedy advertising response. A poll taken in September showed Romney leading Kennedy 43 to 42 percent, and internal Kennedy campaign polls showed a six-point spread against the senator. It had never before seemed possible that a Kennedy could lose an election in Massachusetts. Now it did.

Kennedy reorganized his campaign. Ranny Cooper, the seasoned poltical operator and former Kennedy chief of staff who had told me about the Labor Committee job, joined the campaign team. In early October, after Congress adjourned, Kennedy came home and barnstormed the state. His high energy level roused his allies as well as ordinary voters, putting to rest speculation that he was tired or had lost interest in his job. John F. Kennedy Jr., Ethel Kennedy, and many other Kennedy family members, President and Mrs. Clinton, Vice President Al Gore, and Jesse Jackson all came to Massachusetts to campaign for him. Supporters mobilized advertisements, endorsements, voter contact drives, and events. Leaders in Massachusetts health care, education, labor, civil rights, technology, the arts, and even the fishing industry signed on. The breadth of support was remarkable. A few days before the election members of the Massachusetts Carpenters Union joined with the Gay and Lesbian Task Force in an impressive march through Boston, holding Kennedy signs and banners. He began to turn the election around as the campaign reached the homestretch.

Kennedy took out a million-dollar personal loan on his house in Virginia to signal that he would match the Republicans in spending. His first television ad stressed his career-long commitment to improving the living standards of Massachusetts’s working families and his achievements in health care, education, jobs, and wages. Then came a big break: the campaign received a call from a labor union in Marion, Indiana, telling us that we should look carefully at how a stationery factory there, acquired by Romney’s firm, had been unfair to its workers. The new management cut jobs, increased insurance premiums, and eliminated the union. Kennedy’s advertising strategist, Bob Shrum, sent a film crew to Indiana and located and interviewed many of the laid-off workers who were understandably hostile to Romney. Their testimonials about their unhappy fate at his hands, broadcast over and over again, painted Romney as no friend of working people. This tactic was so devastating to Romney that the Obama campaign used it again in 2012.

The challenge for the campaign was to convince voters to reject the Republican wave building across the country and stick with the Democratic values for which Kennedy had always fought. To that end, Kennedy reenergized his campaign with his speech at a packed rally in Boston’s Faneuil Hall on October 16. Hearing that speech in person was one of the most memorable moments of the campaign. The text could have been delivered in thirty minutes, but it took an hour because applause interrupted him fifty-seven times. It was a call to battle and an uncompromising assertion of liberal principles.

I stand for the idea that public service can make a difference in the lives of people. I believe in a government and a senator that fight for your jobs. I believe in a government and a senator that fight to secure the fundamental right of health care for all Americans. I believe in a government and a senator that fight to make our education system once again the best in the world. If you send me back to the Senate, I make you one pledge above all others. I will be a senator on your side. I will stand up for the people and not the powerful.

Kennedy’s strategists had hoped to avoid any debates with Romney, as incumbents with healthy leads usually do, but as the polls showed, the race was a toss-up; debates became inevitable. In the first, held on October 25, Romney started out strong, attacking Kennedy as unresponsive to the prevalence of crime. But as the debate progressed, he became rattled. He reiterated a point from his television ads, claiming that the Kennedy family had made millions from federal leases, but the attack backfired when Kennedy responded, “Mr. Romney, the Kennedys are not in public service to make money. We have paid too high a price for our commitment to public service.”

As the debate continued, Romney appeared increasingly out of his depth. He seemed to have little grasp of what a senator actually does, of what his own proposals would cost, and even the geography of Massachusetts. Kennedy effectively put his enthusiasm, his record for Massachusetts, his family tradition of public service, his mastery of legislation, and most of all his identification with the needs and interests of working families on full display for the largest television audience for a political debate in Massachusetts history.

When the TV lights went off, the Kennedy campaign staff believed the tide had turned. Viewer polls showed Kennedy the decisive winner, and a week after the debate Kennedy had a twenty-point lead in one poll and a ten-point lead in another. But there had been so much volatility in the polls throughout the campaign that no one took a single poll as the final word. The senator continued barnstorming with great enthusiasm; there was no doubting his zeal for the fight.

When the polls closed at 8:00 on election night I drove straight to the Park Plaza Hotel in the Back Bay section of Boston. Kennedy people arrived from all over the state—the army of volunteers who’d covered each of the 2,500 polling places, as I had in Gloucester. Some had driven from the Berkshires, more than two hours away to the west, others from Cape Cod, two hours to the south. Everyone wants to be with their candidate on Election Night.

I took the elevator to the twelfth floor, where private meeting rooms were reserved for staff and Kennedy had his private suites. Exit polls had Kennedy comfortably ahead, and one of the television stations had projected him the winner. I took the corridor to the Kennedy suite, to see the senator and Mrs. Kennedy and congratulate them before they went downstairs to the ballroom to make their victory speeches. I told the senator things looked good based on my day in Gloucester.

“Good to see you. It looks like we’re okay,” he said. “Thanks so much for helping. We’ll get right back on health care and the minimum wage.”

Kennedy hadn’t yet heard from Romney. While he waited, he was busy placing calls to Democratic officials and candidates across the country, wishing them well, congratulating those who were already clear winners, commiserating with those who’d lost. For years President Clinton had reminded Kennedy how much it meant to him that Kennedy had been one of the few national figures who’d called him in Little Rock on Election Night in 1980, when Clinton had just lost his first reelection campaign for governor of Arkansas.

Downstairs a stage had been constructed in the ballroom, a band was playing, and balloons and signs were everywhere. On stage were the senator’s nieces and nephews, sisters, children and grandchildren. At 10:00 he and Vicki pressed up onto the crowded stage, joyful, waving, the senator punching his fist in the air, Vicki nodding, smiling. Hunched over a bit, like a boxer protecting his chin, he kept waving his arm up by his head, mouthing the words, “Thank you. Thank you.” The band was playing louder and faster, and the cheering wouldn’t stop. Finally Kennedy waved the crowd to silence.

“I’ve had a call from Mitt Romney, and he’s congratulated us on winning the election,” he announced. The crowd erupted again, cheering uncontrollably. Kennedy again put up both hands for silence.

“I want to thank all of you for what you’ve done. . . . I thank the voters of Massachusetts. . . . I thank my family, my sisters, my nephews and nieces. I want to pay special tribute to the love of my life, Vicki.” More cheering. Then he introduced his family. “My daughter Kara, my son Teddy. My son Patrick is not here. He’s in Rhode Island tonight, celebrating his election today to the United States Congress. I saw him earlier this evening in Providence.” The crowd roared.

The senator brought the crowd to silence once again and enthusiastically belted out his campaign mantra: “We won because people understood what we stood for and what battles we would fight. We will never stop fighting to improve jobs and wages, for better schools, for health care for all.” The room erupted with cheers once again. Then the pledge: “We will go back to Washington to carry on the fight to improve the lives of ordinary working Americans. With all the strength I have, I will make that fight.” As the cheering continued, the senator made his way down from the stage and into the crowd to thank people in person. The stage emptied behind him, but the euphoria among the packed crowd stayed strong as volunteers pressed forward to congratulate him and Vicki.

When the formal vote count was tallied, Kennedy’s victory margin was 58 to 41 percent, close to the average in his five previous elections. The vote total from Gloucester was 6,846 for Kennedy and 4,185 for Romney, a 62 to 38 percent advantage.

By 11:00 the senator was back upstairs, and the ballroom was empty. I found myself wandering across the floor amid the leftover balloons and placards from the celebration feeling a mixture of relief and joy.

REPUBLICANS SWEEP THE NATIONAL ELECTIONS

Before midnight I went upstairs to the staff meeting rooms, where televisions along each wall were tuned in to Election Night coverage. The mood was very different from the euphoria in the ballroom; here people looked shocked. Each close race was coming in against the Democrats, and it looked more and more likely we would lose the majority in the Senate. Democratic incumbents Jim Sasser in Tennessee and Harris Wofford in Pennsylvania had already lost. Open seats previously held by Democrats Donald Riegle in Michigan, Howard Metzenbaum in Ohio, George Mitchell in Maine, David Boren in Oklahoma, and Dennis DeConcini in Arizona had already gone to Republican candidates. Only a few races had not yet been called, and it looked ominous. By midnight the networks were reporting that the Senate had gone to the Republicans, 52–48.

The news on the House elections was even more stunning; if the trends continued into the morning, Newt Gingrich and the Republicans with their Contract with America would be in charge of the new order in the House of Representatives. The conservative revolution was at hand.

It was almost too much to take in at once. I didn’t know what it would be like to be in the minority. Republicans had been in control of the Senate from 1981 to 1986, the first six years of the Reagan administration, so some of Kennedy’s staff knew the experience firsthand, but back then I’d been a private citizen in Boston.

There would be a Republican majority leader and a Republican chairman of the Senate Labor Committee. So much power lost. I would no longer be staff director to the Committee. Kennedy would no longer control the Committee’s agenda. Our plans for more progress in health care, education, and jobs were all in jeopardy. Everything I had known in Congress would be turned upside down.

I went back to my hotel room and slept badly, torn between the joy of the senator’s reelection and the disaster of the Republican sweep of Congress, between the sweet and the bitter. The sweet mattered more to me; Kennedy’s defeat would have been devastating. But the bitter cast a dispiriting pall over the future.

Early the next morning, the senator and Vicki went to the Park Street subway stop to thank people for their votes. He was thrilled with his victory; he had worked hard and was inspired by his contact with voters. But now he had to go back to Washington, where many of his friends had lost their seats and his party had been handed a devastating defeat. Armed with his unshakable conviction that government is a positive force in American society, he was determined to bring the successful lessons from his campaign to the national party, which was in deep despair over its losses.

When the doors of the Veterans Memorial Elementary School in Gloucester, Massachusetts, opened to admit the first voters at 7:00 in the morning on Election Day 1994, I was standing outside the school holding a red, white, and blue “Kennedy for Senate” sign, “doing visibility,” as they call it in Massachusetts politics. I had taken two weeks off from my job working for Kennedy in Washington to volunteer on the campaign. It was his tradition that for the final weekend and until the polls closed on Election Day, everyone involved in the campaign would leave the Boston headquarters and spread out across the state to help in local cities and towns. I chose to work in Gloucester, an hour north of Boston. Over the long hours in the early morning New England chill, holding my sign and saying “Good morning” to voters, I thought about what had brought me, a fifty-two-year-old lawyer and father of three, to this school and this moment.

I’d grown up in Providence, Rhode Island, and gone to Harvard College. My first job after college was as a Broadway singer in My Fair Lady in summer stock and in Kismet with Alfred Drake at Lincoln Center in New York. After one year in the professional theater I left to go to law school. I thought law and musical theater were the opposite poles in my life, never imagining that singing would become a great political asset, especially when I worked for Kennedy.

When I was in law school at the University of Pennsylvania, part of a generation urged to go into public service by President John F. Kennedy, I worked on my first political campaign, for Governor John Chafee of Rhode Island, a progressive Republican. I drove Chafee around in a yellow and blue truck with speakers on the roof blasting a campaign ditty I’d written: “Keep the man you can trust in Rhode Island, with Chafee we’re moving along. Keep the man you can trust in Rhode Island, and keep Rhode Island strong.” Chafee won the election, and I finished law school. In 1968 he asked me to run his reelection campaign, which I did while studying for the New York Bar Exam. His defeat, due to his courageous support for a new state income tax, was my first political disappointment.

In 1970, while working at a New York law firm, I ran the “Lawyers Committee against the Vietnam War,” raising money for congressional antiwar candidates across the country. One of these candidates, the brilliant antiwar and civil rights activist Allard Lowenstein, recruited me to run a nationwide voter registration drive called Registration Summer the next year. A constitutional amendment lowering the voting age from twenty-one to eighteen had just passed, and we wanted to register young people, who we hoped would help stop the war with their votes. In 1972 I left my law firm and ran Al’s campaign to return to Congress. His loss was another profound disappointment; I was beginning to understand that losses are frequently part of politics and that losing hurts a great deal.

After the campaign the Republican U.S. attorney appointed me an assistant U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York (Manhattan and the Bronx). There I prosecuted corrupt politicians, drug dealers who were part of the infamous “French connection,” tax swindlers, and worked on white-collar and organized crime cases. I conducted over two dozen trials and learned how to make a convincing argument in front of a Manhattan jury, a formidable task for a Bostonian. When my four-year term ended I wanted to go home to New England to reconnect with my family and lifetime friends, so I accepted a job as a lecturer at Harvard Law School. I soon was running Harvard’s trial advocacy program, which I did for twelve years; I also taught prosecution and investigations and started a course called “The Government Lawyer” to encourage students to work in government by showing them the excitement and responsibility involved.

In 1978 the Massachusetts legislature established a special commission to investigate corruption in the state’s public construction projects. Bill Ward, the president of Amherst College, was appointed head of the commission; on the recommendation of Harvard Professor Archibald Cox and Manhattan District Attorney Robert Morgenthau, whom he knew through Amherst, Ward asked me to become chief counsel and executive director. We wanted to excite public opinion about the costs of corruption, which had become a way of life in Massachusetts. We hoped to convince a reluctant legislature to rewrite the laws and fix the problems we would identify. We decided that presenting evidence of the widespread kickbacks that we uncovered was the best way of doing this. Because there were still afternoon papers as well as afternoon and evening news shows that had to be filled, we determined to try to hold full public hearings every morning, and revelations from these hearings became our signature “bribe a day before lunch.” Our eighteen months of public hearings were covered extensively in the media.

One of my favorite bribery cases was that of William Masiello, who ran a pizza parlor in Worcester and decided he could make more money if he opened an architectural firm. Masiello quickly got public work by paying off the Worcester County commissioners and persuading them that there should be a new courthouse in each town in Worcester County, which is why, to this day, that area has four virtually identical courthouses within a radius of fifty miles. Masiello eventually succeeded in winning bribery-greased contracts all over the state.

The Ward Commission served its purpose: the legislature passed criminal laws to strengthen public corruption prosecutions and reform the construction process from bid to completion. It also created a permanent Inspector General’s Office to continue our work.

When the Ward Commission ended in 1981, I was married and the father of three, so for financial reasons I had to think about going back to a law firm. I took a job at Foley, Hoag and Eliot and spent almost eight years there. In the fall of 1988 Gregory Craig, an old friend from the Lowenstein campaign, called to tell me he was leaving his job as foreign policy advisor for Senator Kennedy. He told me that it was a tradition in Kennedy’s office to find candidates to succeed you when you left, and he was calling to urge me to be his replacement.

The idea of working for Kennedy was very enticing, but I wasn’t sure foreign policy was the right fit for me. As I was hesitating about the job, Ranny Cooper, the senator’s chief of staff, called to tell me that there was also a vacancy coming up in domestic policy for staff director for the Senate Labor and Human Resources Committee, which Kennedy chaired. The Labor Committee had jurisdiction over health care, medical research, doctor training, people with disabilities, the Food and Drug Administration, and education, including higher education, student loans, and school reform. It also had jurisdiction over jobs and job training, wages, labor, civil rights in the workplace, and even the arts and children’s issues, such as Head Start and child care.

I wanted to go back to government, but not as a prosecutor. I had learned from prosecuting two cases in which we mistakenly arrested the wrong person that the truth could be elusive and the consequences of mistakes dire. Although the falsely convicted bank robber and the wrongly identified international drug dealer were ultimately released, I no longer wanted to take the chance of ruining a person’s life and spending my time passing judgment on whether what people had done was wrong or criminal. Building people up was more important to me. This was an opportunity to return to a whole different kind of government service, where the goal was no longer being the cop on the beat but using government to try to improve people’s lives. It was irresistible.

Ranny arranged for me to be interviewed for the Labor Committee job by Kennedy and his Boston chief of staff, Barbara Souliotis, in Boston. I met the senator in the restaurant of the Harvard Club at 4:00 p.m. on a Friday, just after he’d finished his steam bath treatment for his bad back. This was the first time I had met him. He came upstairs in his well-pressed blue suit and well shined black shoes (he later told me that Kennedys don’t wear brown), sat at the table, and turned on the famous Kennedy charm: loud, funny, and warm.

“I want you to come work with me,” he said. “This is what we’re going to do: health care, raising the minimum wage, fixing the schools, to start.”

As it was my habit to take notes in every meeting, I grabbed the only available paper—a cocktail napkin—and jotted down what he said: Health care, minimum wage, schools. I felt like accepting on the spot but refrained, instead telling him I would think about it. He said he would see me in Washington.

I flew down for more formal meetings with the staff of the Labor Committee and with Kennedy’s personal staff. The staff members were expert in their substantive areas. I was an expert in none, but I would learn, and I knew how to develop and run a campaign. A week later I went to see Kennedy in his office. He took me out onto the balcony, turned to glance up and down Constitution Avenue, over the Capitol, the Supreme Court, the Washington Monument, and, in the distance, the rows of graves in Arlington National Cemetery, where both his brothers were buried (and where he is now buried). Before I could say anything, he asked me when I could start. I said, “How soon do you need me?”

The answer was February 1989. One of the first things Kennedy told me was that nothing could get done in the Senate unless it was bipartisan. The notion of good and bad guys, which I had been focused on for twelve years, was useless; we had to seek out Senate colleagues, Republicans and Democrats, for everything we did. Kennedy had great respect for the other senators and worked hard to build relationships with those across the aisle. This would prove particularly difficult on health care reform, the cause that was so central to Kennedy and that would be an ongoing focus of my career.

Five extraordinary years later, campaigning in Gloucester, I thought over some of our successes: we had passed landmark legislation through the Labor Committee, including the Americans with Disabilities Act, the Civil Rights Act of 1991 (strengthening the laws against discrimination in the workplace on the grounds of race, religion, or gender), the Family and Medical Leave Act, the Ryan White AIDS CARE Act, and the Child Care and Development Block Grant. Nothing was as important to me as Kennedy’s reelection.

Gloucester was a good place to spend Election Day, a working-class city of thirty thousand with a proud history that had fallen on hard economic times. The median family income was $32,000, close to the national median of $31,278. I thought that many of the voters I saw that day and had talked to over a weekend of phoning and canvassing neighborhoods had probably benefited from the senator’s legislation.

What I’d heard from voters during my time in Gloucester and from the latest polls gave me confidence about the outcome of the election, though the campaign had been the toughest of Kennedy’s long career. First elected to the Senate in 1962 at the age of thirty, he’d been reelected five times but hadn’t had a serious challenge in at least twelve years, until Republicans fielded the impressive Mitt Romney against him.

KENNEDY DEFEATS ROMNEY

Romney was a fresh and promising new face in Massachusetts politics. He was forty-four, clean-cut, and handsome, with a photogenic family and a lot of money that he was willing to plow into the campaign. He’d come to Massachusetts from Michigan to attend Harvard Law and Business schools in 1971 and stayed to make a fortune in the private equity business.

Several factors were working against Kennedy in this race. The storied Kennedy political organization in Massachusetts was out of practice, the senator himself was older and heavier, and the rape trial of his nephew in Palm Beach three years before had taken a toll on his reputation. Across the country Republicans were united, well-financed, and on the offensive. Kennedy was one of their prime targets; they attacked his politics as obsolete and out of touch. Although Massachusetts is regarded as a reliably Democratic state, the voters had elected a Republican governor, William Weld, in 1990, and were preparing to reelect him in a landslide in 1994, on the same ballot as Kennedy. Polls in the spring had shown that only one third of Massachusetts voters thought Kennedy deserved reelection, and, equally ominous, even one third of Democrats thought it was time for a change.1

On the other hand, the senator had one new extraordinary asset: Victoria Reggie Kennedy, whom he had married on July 3, 1992. Vicki was everything he could want in a wife. Beyond being “the love of his life,” as he often said, she was politically very astute and as good as most of his advisors at thinking strategically. They loved talking politics, and she was a great sounding board for his ideas. Despite their busy schedules, they ate dinner together practically every night, most meals featuring a vigorous discussion of politics and policy. She quickly became very popular in Massachusetts and helped to bridge the gap between his public persona and who he was personally, as a father and a husband. People got to know him all over again with Vicki at his side.

The Romney challenge had a strong start partly because Kennedy was busy with obligations that kept him from campaigning. For most of 1994, he was required to remain in Washington, carrying out his senatorial duties, especially working on President Clinton’s universal health insurance bill, so Vicki pitched in as an eloquent surrogate campaigner. The Senate remained in session through August, when it was normally in recess for elections, and as chairman of the Labor Committee, he took the lead on many issues for Clinton. And before his sister-in-law Jackie Kennedy Onassis died in May of that year, he and Vicki had flown back and forth to New York all spring to visit her. Meanwhile Romney’s television advertisements ran throughout the summer without a Kennedy advertising response. A poll taken in September showed Romney leading Kennedy 43 to 42 percent, and internal Kennedy campaign polls showed a six-point spread against the senator. It had never before seemed possible that a Kennedy could lose an election in Massachusetts. Now it did.

Kennedy reorganized his campaign. Ranny Cooper, the seasoned poltical operator and former Kennedy chief of staff who had told me about the Labor Committee job, joined the campaign team. In early October, after Congress adjourned, Kennedy came home and barnstormed the state. His high energy level roused his allies as well as ordinary voters, putting to rest speculation that he was tired or had lost interest in his job. John F. Kennedy Jr., Ethel Kennedy, and many other Kennedy family members, President and Mrs. Clinton, Vice President Al Gore, and Jesse Jackson all came to Massachusetts to campaign for him. Supporters mobilized advertisements, endorsements, voter contact drives, and events. Leaders in Massachusetts health care, education, labor, civil rights, technology, the arts, and even the fishing industry signed on. The breadth of support was remarkable. A few days before the election members of the Massachusetts Carpenters Union joined with the Gay and Lesbian Task Force in an impressive march through Boston, holding Kennedy signs and banners. He began to turn the election around as the campaign reached the homestretch.

Kennedy took out a million-dollar personal loan on his house in Virginia to signal that he would match the Republicans in spending. His first television ad stressed his career-long commitment to improving the living standards of Massachusetts’s working families and his achievements in health care, education, jobs, and wages. Then came a big break: the campaign received a call from a labor union in Marion, Indiana, telling us that we should look carefully at how a stationery factory there, acquired by Romney’s firm, had been unfair to its workers. The new management cut jobs, increased insurance premiums, and eliminated the union. Kennedy’s advertising strategist, Bob Shrum, sent a film crew to Indiana and located and interviewed many of the laid-off workers who were understandably hostile to Romney. Their testimonials about their unhappy fate at his hands, broadcast over and over again, painted Romney as no friend of working people. This tactic was so devastating to Romney that the Obama campaign used it again in 2012.

The challenge for the campaign was to convince voters to reject the Republican wave building across the country and stick with the Democratic values for which Kennedy had always fought. To that end, Kennedy reenergized his campaign with his speech at a packed rally in Boston’s Faneuil Hall on October 16. Hearing that speech in person was one of the most memorable moments of the campaign. The text could have been delivered in thirty minutes, but it took an hour because applause interrupted him fifty-seven times. It was a call to battle and an uncompromising assertion of liberal principles.

I stand for the idea that public service can make a difference in the lives of people. I believe in a government and a senator that fight for your jobs. I believe in a government and a senator that fight to secure the fundamental right of health care for all Americans. I believe in a government and a senator that fight to make our education system once again the best in the world. If you send me back to the Senate, I make you one pledge above all others. I will be a senator on your side. I will stand up for the people and not the powerful.

Kennedy’s strategists had hoped to avoid any debates with Romney, as incumbents with healthy leads usually do, but as the polls showed, the race was a toss-up; debates became inevitable. In the first, held on October 25, Romney started out strong, attacking Kennedy as unresponsive to the prevalence of crime. But as the debate progressed, he became rattled. He reiterated a point from his television ads, claiming that the Kennedy family had made millions from federal leases, but the attack backfired when Kennedy responded, “Mr. Romney, the Kennedys are not in public service to make money. We have paid too high a price for our commitment to public service.”

As the debate continued, Romney appeared increasingly out of his depth. He seemed to have little grasp of what a senator actually does, of what his own proposals would cost, and even the geography of Massachusetts. Kennedy effectively put his enthusiasm, his record for Massachusetts, his family tradition of public service, his mastery of legislation, and most of all his identification with the needs and interests of working families on full display for the largest television audience for a political debate in Massachusetts history.

When the TV lights went off, the Kennedy campaign staff believed the tide had turned. Viewer polls showed Kennedy the decisive winner, and a week after the debate Kennedy had a twenty-point lead in one poll and a ten-point lead in another. But there had been so much volatility in the polls throughout the campaign that no one took a single poll as the final word. The senator continued barnstorming with great enthusiasm; there was no doubting his zeal for the fight.

When the polls closed at 8:00 on election night I drove straight to the Park Plaza Hotel in the Back Bay section of Boston. Kennedy people arrived from all over the state—the army of volunteers who’d covered each of the 2,500 polling places, as I had in Gloucester. Some had driven from the Berkshires, more than two hours away to the west, others from Cape Cod, two hours to the south. Everyone wants to be with their candidate on Election Night.

I took the elevator to the twelfth floor, where private meeting rooms were reserved for staff and Kennedy had his private suites. Exit polls had Kennedy comfortably ahead, and one of the television stations had projected him the winner. I took the corridor to the Kennedy suite, to see the senator and Mrs. Kennedy and congratulate them before they went downstairs to the ballroom to make their victory speeches. I told the senator things looked good based on my day in Gloucester.

“Good to see you. It looks like we’re okay,” he said. “Thanks so much for helping. We’ll get right back on health care and the minimum wage.”

Kennedy hadn’t yet heard from Romney. While he waited, he was busy placing calls to Democratic officials and candidates across the country, wishing them well, congratulating those who were already clear winners, commiserating with those who’d lost. For years President Clinton had reminded Kennedy how much it meant to him that Kennedy had been one of the few national figures who’d called him in Little Rock on Election Night in 1980, when Clinton had just lost his first reelection campaign for governor of Arkansas.

Downstairs a stage had been constructed in the ballroom, a band was playing, and balloons and signs were everywhere. On stage were the senator’s nieces and nephews, sisters, children and grandchildren. At 10:00 he and Vicki pressed up onto the crowded stage, joyful, waving, the senator punching his fist in the air, Vicki nodding, smiling. Hunched over a bit, like a boxer protecting his chin, he kept waving his arm up by his head, mouthing the words, “Thank you. Thank you.” The band was playing louder and faster, and the cheering wouldn’t stop. Finally Kennedy waved the crowd to silence.

“I’ve had a call from Mitt Romney, and he’s congratulated us on winning the election,” he announced. The crowd erupted again, cheering uncontrollably. Kennedy again put up both hands for silence.

“I want to thank all of you for what you’ve done. . . . I thank the voters of Massachusetts. . . . I thank my family, my sisters, my nephews and nieces. I want to pay special tribute to the love of my life, Vicki.” More cheering. Then he introduced his family. “My daughter Kara, my son Teddy. My son Patrick is not here. He’s in Rhode Island tonight, celebrating his election today to the United States Congress. I saw him earlier this evening in Providence.” The crowd roared.

The senator brought the crowd to silence once again and enthusiastically belted out his campaign mantra: “We won because people understood what we stood for and what battles we would fight. We will never stop fighting to improve jobs and wages, for better schools, for health care for all.” The room erupted with cheers once again. Then the pledge: “We will go back to Washington to carry on the fight to improve the lives of ordinary working Americans. With all the strength I have, I will make that fight.” As the cheering continued, the senator made his way down from the stage and into the crowd to thank people in person. The stage emptied behind him, but the euphoria among the packed crowd stayed strong as volunteers pressed forward to congratulate him and Vicki.

When the formal vote count was tallied, Kennedy’s victory margin was 58 to 41 percent, close to the average in his five previous elections. The vote total from Gloucester was 6,846 for Kennedy and 4,185 for Romney, a 62 to 38 percent advantage.

By 11:00 the senator was back upstairs, and the ballroom was empty. I found myself wandering across the floor amid the leftover balloons and placards from the celebration feeling a mixture of relief and joy.

REPUBLICANS SWEEP THE NATIONAL ELECTIONS

Before midnight I went upstairs to the staff meeting rooms, where televisions along each wall were tuned in to Election Night coverage. The mood was very different from the euphoria in the ballroom; here people looked shocked. Each close race was coming in against the Democrats, and it looked more and more likely we would lose the majority in the Senate. Democratic incumbents Jim Sasser in Tennessee and Harris Wofford in Pennsylvania had already lost. Open seats previously held by Democrats Donald Riegle in Michigan, Howard Metzenbaum in Ohio, George Mitchell in Maine, David Boren in Oklahoma, and Dennis DeConcini in Arizona had already gone to Republican candidates. Only a few races had not yet been called, and it looked ominous. By midnight the networks were reporting that the Senate had gone to the Republicans, 52–48.

The news on the House elections was even more stunning; if the trends continued into the morning, Newt Gingrich and the Republicans with their Contract with America would be in charge of the new order in the House of Representatives. The conservative revolution was at hand.

It was almost too much to take in at once. I didn’t know what it would be like to be in the minority. Republicans had been in control of the Senate from 1981 to 1986, the first six years of the Reagan administration, so some of Kennedy’s staff knew the experience firsthand, but back then I’d been a private citizen in Boston.

There would be a Republican majority leader and a Republican chairman of the Senate Labor Committee. So much power lost. I would no longer be staff director to the Committee. Kennedy would no longer control the Committee’s agenda. Our plans for more progress in health care, education, and jobs were all in jeopardy. Everything I had known in Congress would be turned upside down.

I went back to my hotel room and slept badly, torn between the joy of the senator’s reelection and the disaster of the Republican sweep of Congress, between the sweet and the bitter. The sweet mattered more to me; Kennedy’s defeat would have been devastating. But the bitter cast a dispiriting pall over the future.

Early the next morning, the senator and Vicki went to the Park Street subway stop to thank people for their votes. He was thrilled with his victory; he had worked hard and was inspired by his contact with voters. But now he had to go back to Washington, where many of his friends had lost their seats and his party had been handed a devastating defeat. Armed with his unshakable conviction that government is a positive force in American society, he was determined to bring the successful lessons from his campaign to the national party, which was in deep despair over its losses.

Product Details

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster (November 22, 2016)

- Length: 528 pages

- ISBN13: 9781476796161

Browse Related Books

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Lion of the Senate Trade Paperback 9781476796161

- Author Photo (jpg): Nick Littlefield Photograph courtesy of Foley Hoag LLP.(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit

- Author Photo (jpg): David Nexon Photograph by Rahima R. Rice(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit