Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

Table of Contents

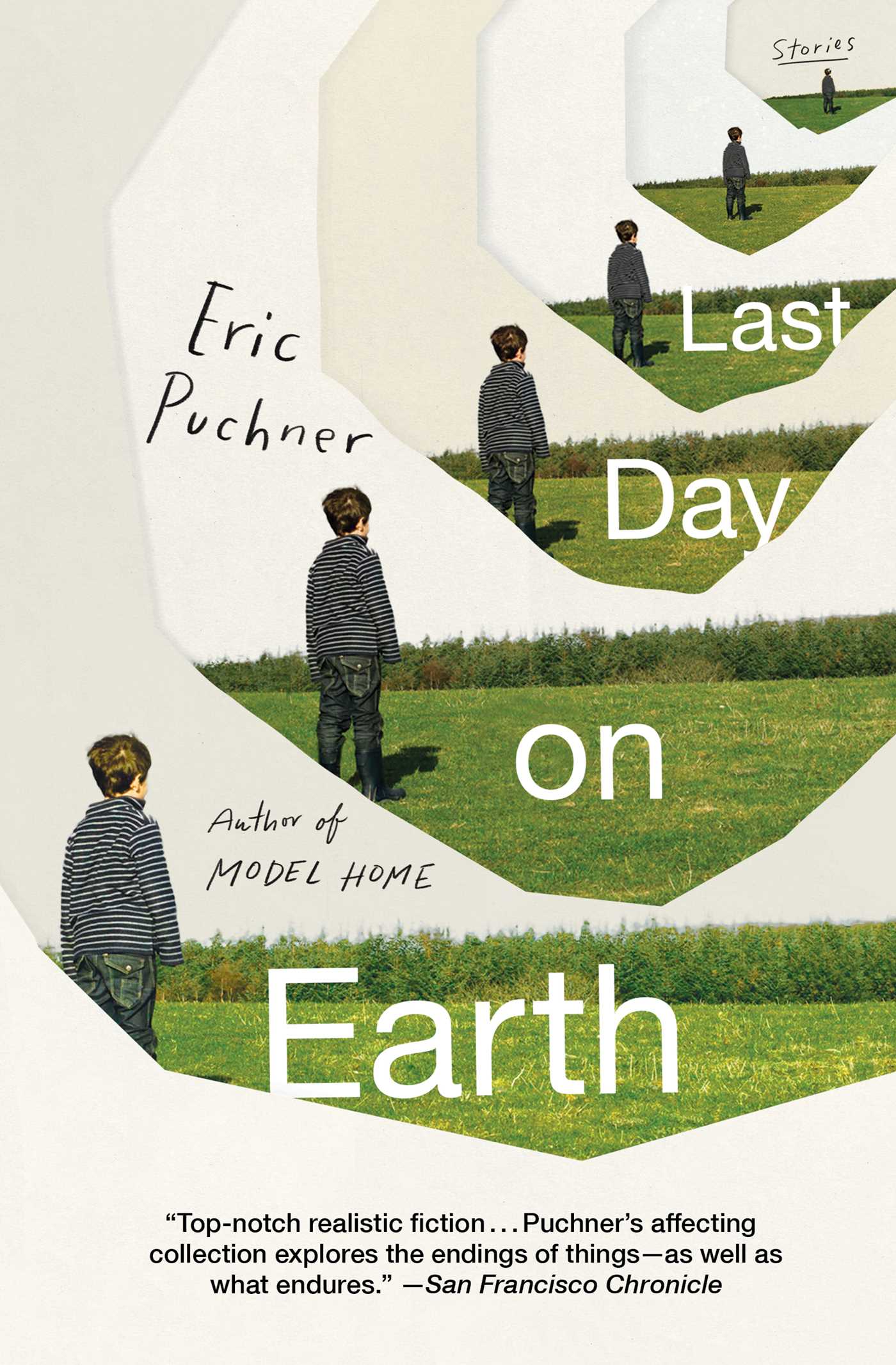

About The Book

A boy on the edge of adolescence fears his mother might be a robot; a psychotically depressed woman is entrusted with taking her niece and nephew trick-or-treating; a reluctant dad brings his baby to a debaucherous party; a teenage boy tries to prevent his mother from putting his estranged father’s dogs to sleep. Ranging from a youth arts camp to an aging punk band’s reunion tour, from a dystopian future where parents no longer exist to a ferociously independent bookstore, Last Day on Earth revolves around the endlessly complex, frequently surreal system that is family.

Eric Puchner, hailed as “technically gifted and emotionally insightful” (The New York Times Book Review), and someone who “puts the story back in short story” (San Francisco Chronicle), delivers a gloriously original, utterly memorable collection that evokes both the comedy and tragedy of our lifelong endeavor to come of age.

Excerpt

It was the summer of the cicadas. They’d been living underground for seventeen years, but now they tunneled out of the earth and climbed the trees and telephone poles, breaking free of their bodies and sprouting wings. They left their old selves clinging to branches, like perfect glass replicas. Overnight, it seemed, the ancient oaks bubbled and seethed and turned into enormous growths of coral. Dogs went crazy, digging in the dirt and gobbling up white nymphs by the dozens. The sidewalks shimmered like streams. We collected shells in our shirts and made necklaces that we wore around like witch doctors. The wings were amazing things, veined and delicate as a fairy’s, and we harvested them from corpses or plucked them from still-buzzing cicadas in order to frighten girls. The bugs rarely took flight, but our neighbor, Mrs. Palanki, refused to leave the house without her umbrella, running to the car with her head ducked down, as if pummeled by rain.

This was in Guilford, a wealthy section of Baltimore, where summers usually consisted of badminton and touch football in the street and endless pickled mornings of blindman’s bluff in the pool. We’d run home every day for BLTs. The strangest thing that happened was the occasional bat inside the house.

But now the cicada noise was so deafening we had to yell at each other to be heard. Outside it was like a train roaring by. The insects themselves were black and ugly, with beady orange eyes that looked like fish eggs. Everywhere—in the trees, on gutter spouts, on the bill of someone’s cap—they seemed to be growing second heads. It took us a while to figure out what was going on. They fastened themselves together, wings enfolded, so that you couldn’t tell where one bug ended and the other began.

“Screwing,” Stefano Giordano shouted. He was thirteen, a year older than me, and an authority on sex. The cicadas were smooshed together on the windowsill outside his bedroom. The rest of us gathered around.

“No way,” I said.

“That’s what my dad said. The male dies right after, and the female lays her eggs in a tree.”

We were skeptical until we saw it happen: the slow uncoupling, then the one buzzing off somewhere while the other remained on the windowsill. After a while it dropped to the ground and its little legs began to curl up. I had never really watched something die before. It was slow and punctilious and kind of a letdown. I kept thinking how the bug was older than I was, yet had only gotten to see the world for a few days.

* * *

In the middle of the noise and chaos of the cicadas that summer a new family moved into our neighborhood. They’d come from California, we heard, and I can’t imagine what they must have thought of their new home. We watched from our bikes as the movers unloaded their things, crunching through the cicada shells at their feet. It was miserably humid, and furniture kept slipping out of the movers’ hands. One of them, cursing in a foreign language, threw a tennis ball at the maple tree in the front yard, and for a moment the sky was like a popcorn popper swirling with bugs.

The next day my mom baked some brownies, and I walked with her under the frantic buzzing oaks. The house our new neighbors had moved into was an old Victorian, smaller than ours, with a peeling front porch and gabled windows popping out from the roof. The previous owner, Mrs. Winters, had died several years before and bequeathed it to her only daughter, who’d let it go vacant before deciding to move in herself. In the time it lay empty the house had become a favorite topic of my mother, who liked to speculate on what it looked like inside. Normally a lovely and compassionate woman, she took a devout interest in the deterioration of other people’s homes. What, pray tell, have the Morrisons done to their kitchen? she’d ask at dinner, pausing over her Brussels sprouts, or, The Sieglers have really let their garden go to pot.

She rang the bell, and Mrs. Winters’s daughter answered the door, dressed in a tunic with little paisleys on it, her long ferny lashes seeming to stick together for a second when she blinked at us. She looked, I thought, like the sort of woman a movie monster might snatch from a crowd. At thirty-five, my mother was one of the younger parents on the block, but watching her greet our new neighbor I felt for the first time that she was old. The woman introduced herself—Karen Jennings was her name—and stared past us at an icicle of cicadas hanging from a nearby oak.

My mother made a face. “Hideous, aren’t they?”

“Oh, I don’t know. Something kind of fabulous about them, don’t you think?” Mrs. Jennings closed her eyes for a moment, as if listening to the trees. “They certainly make your life, um, biblical.”

My mom tried to smile at her and peer into the house at the same time. I had never heard anyone’s mother talk like this before, describe a plague of insects as “fabulous.” A thrill breezed through me. As I ducked out from under my mother’s hand, a boy who looked about my age came to the door with something jutting from his lips. A cigarette. Little shreds of tobacco poked out of the crumpled tip. My mother stopped craning her neck to see inside and took a step backward.

“This is JJ,” Mrs. Jennings said.

“Jules, Mom.”

“Jules,” she said, rolling her eyes.

My mom was staring at the boy’s lips. “Where did you get that cigarette?”

“I’m not actually smoking,” he said without taking it from his mouth.

“It’s just for fun,” Mrs. Jennings said. “In his case, at least. I’m in it to the grisly end.”

The boy plucked the cigarette from his lips and wedged it behind his ear. I did not like the looks of him. He had freckles like me, except he was skinny and frizzy-haired and wearing long pants—corduroys—in the middle of summer. Plus he had something wrong with his eye. One of his pupils had a black line spoking out from it, like the hand of a watch stuck at six o’clock. He caught me staring at it, I think, because he turned away and went back inside the house. It seemed impossible to me that this freaky kid and gorgeous mother were related.

My mother hesitated when Mrs. Jennings invited us in for some coffee, but her curiosity got the best of her and I followed her into the Jenningses’ house, which was still lined with boxes. There were paintings everywhere, leaning against some of the weirdest furniture I’d ever seen. One chair looked like a bunch of curtain rods with a strip of brown-spotted hide stretched across them, as if a lunatic had tried to make a trampoline out of a cow. I couldn’t resist touching it as I passed. Mrs. Jennings took the brownies from my mother and served them on plates that didn’t match, along with something that looked like ice cubes rolled in pink powder. “Turkish delight,” she called the cubes, explaining how she’d ordered them from a shop in the East Village. I didn’t know what the East Village was, but my mom’s expression said that it was a place she didn’t care for.

Chewing on a cube, whose deliciousness surprised me, I wandered over to a painting leaning against the far wall, an eerie desert scene with a circular forest in the middle of it surrounded by a fence. In the foreground, stretching toward the forest, was an animal I didn’t recognize. It was strange and horrible-looking, something like a hairless zebra but with its head sprouting vertically from its neck and a little tadpole mouth. It didn’t have any ears. Looking closer, I saw that the opening to the forest was framed by a pair of enormous female legs, spread like the giant doors of a gate.

“That’s the sex painting,” Jules said to me, checking to see we were out of earshot.

“Sex?”

“See, it’s a giant penis. And that’s supposed to be a vagina. It’s surrealist. One of my dad’s friends painted it.”

I inspected it with deeper interest. Above the sex painting, perched on the mantel, was a framed photograph of a dapper-looking man with a sunburned nose. It was a large, handsome, mesmerizing nose, and probably often sunburned. No photos but this one had been unpacked—at least that I could see.

“Where’s your dad?” I asked. “At work?”

“He’s dead.”

The way he said this, eyes fixed to the floor, made me stop asking questions. While my mother updated Mrs. Jennings on the neighborhood and the history of its poorly maintained homes, Jules offered to show me his room, then surprised me by taking me down a long flight of stairs to the basement. A lightbulb dangled from the ceiling, flickering on and off like a ship’s. Jules led me through the dank cellar to his room, which smelled of fresh paint. The only decoration was a single poster, one of those space pictures of a galaxy abloom with color, the sort of thing I imagined you might see on your way to the afterlife.

“That’s the Cigar Galaxy,” Jules said. “Messier Eighty-two.” He sounded bored, as if anyone with half a brain would know what the Cigar Galaxy was. He took the cigarette from his ear and tweezed it between two fingers, like someone on TV. “Are you familiar with the multiverse?”

“The what?”

“The multiverse. Like our universe is just one of trillions of universes out there. Commonly known as the many-worlds interpretation.”

“That’s stupid,” I said.

“My dad’s a physicist. Was. He told me all about it.” He pointed his cigarette at my chest. “Probability-wise, there’s a parallel universe out there where you and I are talking right now, exact same conversation, everything, but you’re wearing a green shirt instead of a blue one.”

I looked down at my shirt. I was starting to feel a little funny. I’d never heard a twelve-year-old use expressions like “probability-wise” before. This was 1987, before the World Wide Web, before loony ideas were as prevalent as the cicadas buzzing outside. I was beginning to feel trapped under the earth.

“The possibilities are literally infinite,” Jules said. He narrowed his eyes. “If you’ve learned to navigate them.”

“What the hell are you talking about?”

“I’m saying that navigation is possible.” He leaned into me, and his face was suddenly leering. “What girl would you most like to fuck?”

The word startled me. I had the impression it was the first time he’d ever said it out loud. “Phoebe Merchant,” I said, then immediately regretted it. I didn’t know why I’d confessed this to him—perhaps because no one had ever asked me so bluntly. Phoebe was the girl who lived across the street. She had long black hair she could wrap around her neck like a noose and braces on her teeth, which kept my hopes tragically alive. Sometimes Stefano Giordano and I would walk down to the racquet club and spy on her as she played tennis, staring at the pink sunrise of her underpants as she bent over to wait for a serve.

“There’s a universe out there, believe it or not, where you’re nailing her brains out.”

Jules opened a door beside his desk and revealed a room with a folding chair in it and lots of cobwebby shelves built into the walls. A root cellar, he called it. He told me to go inside and sit down. Maybe because he’d impressed me with the word “fuck,” I obeyed him. There was a stash of crumpled-looking cigarettes on a paper plate on the floor, as if he spent a lot of time sitting in there by himself.

No sooner had I sat in the chair than Jules closed the door. I rattled the knob, but he’d locked it somehow and it wouldn’t turn.

“Let me out of here!”

“Relax and try to enjoy the trip. Of course, you can’t think of it like travel. More like diving underwater and coming back up in a different place.”

“I’ll kill you!” I said. I began to kick the door.

“Stop doing that,” he said pleasantly, “or I’ll erase you from the earth.”

I stopped. It was dark, but my eyes were adjusting to it and the corners of the root cellar began to reverse themselves into existence. I pressed my ear against the door but couldn’t hear much of anything, just a faint rhythmic humming, what I imagined to be the roar of the cicadas outside. Maybe it was because of the dark, or because I was inside where the noise didn’t belong, but the sound seemed to emanate from my own brain. I wondered if Jules had left the bedroom. Perhaps he’d tell everyone I went home. I’d be locked up in the root cellar forever, starving to death while the police scoured the city, rotting at long last into a pile of bones. Pharaoh pharaoh pharaoh, the cicadas sang. To keep from panicking, I closed my eyes and tried to imagine what I’d look like in a different universe, one where girls fell miraculously at my feet. I would not have freckles all over my arms. My hair would not be red. It would be brown, like my brother’s, and I wouldn’t be embarrassed by how pale I was every time I had to be Skins during soccer practice.

When Jules opened the door he was smiling. It was a weird smile, curled around his cigarette as if he were trying to keep himself from eating it. My hands were shaking. I pushed him as hard as I could and he sprawled across the floor, the cigarette flying out of his mouth, but the smile didn’t leave his face.

* * *

That evening at dinner, my mom couldn’t stop talking about the Jenningses’ house. She seemed particularly interested in the cigarette dangling from Jules’s mouth, which she blamed entirely on Mrs. Jennings. To me the cigarette seemed unique proof that the kid was deranged, but to my mother it was somehow connected to the paintings and the cow furniture and the mismatched plates. She had always seemed fearless to me—once, when we were camping in Canada, she’d scared away a bear with a canoe paddle—so it was weird to hear her recount these details so obsessively, holding them up like treacherous, snapping things.

“And she served these horrible pink sweets,” my mother said, ignoring the plate of meatloaf in front of her. “Turkish delights. I couldn’t help noticing she didn’t eat any herself.”

My father, for his part, seemed to accept my mother’s judgment. He was an internist at the hospital and grateful enough that my mom had dinner waiting when he came home, treating each incarnation of stroganoff or turkey Tetrazzini as if it were the Second Coming of Christ. He’d close his eyes as he ate and tell her she was the best “chef” in Maryland. On his days off he liked to shoot things out of the sky and bring them home for my mother to clean. Our freezer was a necropolis of birds. When he wasn’t shooting things, he horsed around with us in the backyard or tried to play catch, though he treated it like an amusingly absurd game he had no real interest in. Eventually he would drift off and take his hunting dogs out of the kennel, two German shorthaired pointers who froze into trembling statues at the sight of an animal. He spent hours running them up and down the yard. My father may have felt guilty for spending so much time with his dogs, or for all those ducks and pheasants my poor mother had to pluck, because he was always telling her how beautiful she was, a source of enduring mortification to me. Sometimes he whispered in her ear and she giggled in a way that made me want to untie my shoes so I could focus on tying them again. Theo, my older brother, called these displays “child abuse.” It was one thing in the privacy of our home but quite another at, say, an Orioles game, where they ran the risk of ending up on TV. Sometimes my father would look at us when he flattered her, and I wondered who these lavish displays were for. Other times he’d enter one of his “funks,” as my mother put it, retreating to his office in the attic and failing to emerge for dinner, but we’d come to accept them—like the sour-refrigerator smell he brought home from the hospital or the scratchy brown beard he sometimes groomed with a little comb—as part of the unremarkable mystery of his life.

“He’s a total freak job,” I said, steering the subject back to Jules. I explained about his eye and how it looked like a little clock.

“Sounds like a coloboma of the iris,” my father said, frowning. He scratched his beard, which had begun to go a bit gray. “Benign mutation, probably. Anyway, what’s a freak job?”

“A person of unsound mental fitness,” Theo said. At fourteen, he considered himself something of a liaison between generations. He hadn’t bothered to change after lacrosse practice, and the giant shoulder pads he was wearing made his head look like a voodoo hex. “Why’s he such a freak?”

I’d been thinking of the multiverse, but something—a tingle of fear—kept me from bringing it up. “He’s got a picture of a woman’s open legs.”

“What?” my mother said.

My father seemed intrigued. “An actual picture?”

I nodded. “A zebra’s about to enter them.”

My mom, who clearly hadn’t seen the picture, had turned white. She was looking at my father.

“It’s surrealist,” I explained, feeling—now that I’d seen my parents’ reaction—an itch to defend it.

“I don’t want you going over there again,” my mother said sternly.

I glanced at the painting of a man and woman in old-fashioned clothes that hung in our dining room. They were floating in a rowboat, the woman trailing her fingers in the water while the man gripped the oars. I’d never thought much about this picture, one way or the other, but suddenly it seemed like the stupidest thing in the world.

“I’ll tell you what I heard,” Theo said, shaking some ketchup onto his plate. “His dad offed himself. Shot himself in their minivan. And it was the kid that found him, I guess, in the backseat.”

“Who told you that?” my mother said, frowning.

Theo shrugged. “Zachary Porter.”

“Zachary Porter doesn’t know anything,” I said, though it was only the idea of Mrs. Jennings owning a minivan that upset me.

* * *

Before long more rumors surfaced about Mr. Jennings: he hadn’t killed himself but had been murdered; he’d been experimenting with drugs and had jumped off a roof; he’d shot himself to get away from Mrs. Jennings, who’d invented his madness in order to get to his money. The rumors were made worse by Mrs. Jennings herself, who’d begun taking aimless walks around the neighborhood in black boots that zipped up to her knees, chain-smoking her way past our yards while cicadas ratcheted above her. Even when we weren’t infested with bugs, people in Guilford didn’t wander around for no reason—the best theory we could come up with was that it was for her health, a form of exercise, but that didn’t explain the boots and the cigarettes and the way she stopped in the middle of the sidewalk to stare up at the trees, tusks of smoke streaming from her nostrils.

Sometimes Jules would accompany her on her walks. Once, taking the trash out after dinner, I saw them stop at the sapling near the end of our driveway so that Jules could pluck a cicada off one of its leaves, pinching the thing between his fingers, where it made a sound like a windup toy when you turn the key the wrong way. He held it up to Mrs. Jennings’s ear, and she laughed. How horrified my mother would be, I thought enviously.

It wasn’t until the Biscoes’ annual Fourth of July barbecue that I actually talked to Jules again. People stood on the lawn drinking wine coolers and sodas, doing their best to distract themselves from Brood X. This was what the newspapers were calling the cicadas. They’d be mating for another couple weeks, supposedly, before the females laid their eggs in the trees and began to kick off like the males. Mr. Biscoe lit his stainless-steel grill and a few bugs came flying out of it in flames, weaving around as if they were drunk.

“Man oh man,” Crawford Tuttle said, staring at Mrs. Jennings, who was wearing sunglasses and the black leather boots. She’d shown up to the barbecue with Jules and a plate of asparagus dressed up in little scarves of meat. The meat was actually tied onto the spears. “I’d like to give her a samurai mustache.”

“What the hell does that mean?” Stefano Giordano said.

Crawford shook his head. “If I have to explain it, you wouldn’t understand.”

“Samurais don’t even have mustaches. They have goatees.” Stefano turned to me, disgusted. “He makes this crap up.”

I was barely listening, too distracted by Phoebe Merchant on the trampoline. She was joking around with a friend of hers, trying to double-bounce so she went extra high. She was not as beautiful as Mrs. Jennings—her mouth sloped to one side when she smiled, as if she were trying to scratch an itch on her face without touching it—but the way her hair stayed in the air after the rest of her had landed seemed like a rare and heartbreaking thing. Last night I’d had a dream about her: we were married, living in a cabin with two kids, both of whom had braces even though they were babies.

“So the latest news flash?” Stefano said, lowering his voice. “What happened to her husband? He went schizo.”

“How do you know?”

“My mother told me,” Stefano said. “Her cousin’s friend knew him in Berkeley. They used to teach at the same college.”

“But he’s dead,” I explained. “Jules told me himself.”

Stefano shrugged. “Maybe he OD’d on his meds or something.”

“I’m just glad she’s unattached,” Crawford said, watching Mrs. Jennings pick up one of her hors d’oeuvres. She closed her eyes and tipped her head back like a bird before taking a bite. “Jesus. I’d like to give her a Sicilian shampoo.”

Jules, who’d been standing beside his mother the whole time, noticed me finally and smirked. Even though it was humid enough to leave a puddle, the freak was wearing cords again. Stefano and Crawford insisted I introduce them. The idea was that they’d cozy up to Jules and get invited to Mrs. Jennings’s house, where they’d be able to impress her with their knowledge of modern art.

“How’s the Cigarette Galaxy?” Crawford asked, after introducing himself. I’d told him about the poster in Jules’s room.

“The what?” Jules asked.

“The Cigar Galaxy, he means,” I said.

Jules glanced at me, just for a second. His mother had sauntered off with her asparagus. “I have no idea what you’re talking about.”

Stefano raised his eyebrows. “Do you or don’t you, as Errol here claims, have a poster of the Cigarette Galaxy in your room?”

“I have a poster of Albert Einstein. Maybe he’s confused.” Jules looked at me curiously. “Anyway, I’ve never met him before in my life.”

I gawked at him. “What are you talking about? You locked me in the root cellar!”

“We don’t even have a root cellar.”

Stefano and Crawford stared at me. I hadn’t told them about the root cellar, mostly out of humiliation. Jules smiled in a new polite way and then wandered back to his mother, who was roaming the yard with her asparagus plate, as if it were not the Biscoes’ party but her own. Stefano and Crawford were still looking at me, but before I could defend myself Phoebe Merchant dismounted the trampoline and landed in the grass a few yards away from us, batting furiously at her hair. I thought she was on fire. I ran to help her, prepared to tackle her on the lawn, but she’d stopped swatting her head and was staring at something in the grass.

I looked down and saw two cicadas locked together, their rear halves magically fused. One of them buzzed its wings. “What are they doing?” Phoebe Merchant asked.

I blushed. “Mating, I think.”

“What do you mean?”

“I’m sorry” was all I could say. I looked at Stefano and Crawford for help, but they were standing out of earshot, their faces blank with astonishment.

“Yug,” she said, shivering in disgust. “Are there more on me?”

She bent down so that her hair fell over her face. She seemed to want me to search it. I reached up and touched the sweaty roots of her hair, feeling the warmth of her scalp underneath. My heart was racing. I kept my fingers moving so she wouldn’t feel them tremble.

“Nothing,” I said, dropping my hands.

“No eggs or anything?”

“The female leaves the male to die,” I said knowledgeably. “She lays her eggs in a tree.”

“The male . . . dies?”

I nodded. Something in her voice—deliberate as a wink—made my knees catch. She thanked me for checking her hair, smiling in that lopsided way, and I realized she was trying to hide her braces. She dashed off to the cooler to grab a Sprite. I couldn’t speak. The Biscoes’ lawn was green and striped like a watermelon, cluttered with sporting goods. I looked around for Jules, who’d either missed my interaction with Phoebe Merchant or was still pretending he didn’t know me or anything about my tormented desire.

Eventually, dusk began to melt the windows, turning the houses into aquariums of light, and we climbed up on the Biscoes’ roof with some fireworks Stefano’s cousin had brought him from West Virginia. Jules seemed to be gone—or at least I’d lost sight of him. From the roof the party looked small and pointless, and I had the feeling that maybe everyone wanted to go home but were all under some kind of spell. I spied my father standing near the Biscoes’ badminton net, talking to Mrs. Jennings. My mother had said goodbye to me earlier—I’d assumed for both of them—so it surprised me that he hadn’t left. He was holding a badminton racket in one hand and swinging it back and forth. As he spoke, Mrs. Jennings twined one leg behind the other, stork-like, so that her feet were on opposite sides of each other. She said something and touched his arm, and my father pitched his head back and guffawed. I was astonished. I’d never seen him laugh like that before, straight into the air as if he were trying to catch his own spit.

* * *

The next evening my father pulled into the driveway after work and went straight out to the front yard to run his dogs. I watched him through the window. He always took the dogs out back, where our property sloped down to a creek, so it was odd to see Dax and Caramel pinballing around the tiny, fenced-in lawn, gobbling up bugs. My father’s back was turned to the house, and when he swung around suddenly, lingering in the last bit of sun, my heart froze. He’d shaved off his beard.

When he finally came inside, my mother said theatrically, as if presenting him to us, “What do you think, boys? Does he look ten years younger?”

On the left side of his jaw was a little brown mole, as obscene to me as the beakiness of his lips. I’d seen pictures of him without a beard, prehistoric snapshots curling at the corners. Theo didn’t say a word but just kept staring at his face.

“God knows what possessed him,” my mother said. “I haven’t seen his chin since we got married.”

Her voice sounded sharper than her words, as if she were making fun of him. My father blushed. He started to say something but then stopped, thinking better of it, his nostrils hard as a statue’s. He touched my head to say hello and then disappeared upstairs to his office.

The rest of the night I couldn’t shake the feeling of trespassing in my own house. I lay in bed in the dark and stared at the trophies on my dresser, watching the golden swimmers strain toward me, ready to dive from their plinths. My parents argued in their bedroom. I’d heard them fight before, on rare occasions, but there was something different now about their voices, which sounded angrier the softer they got. I tried to picture Phoebe Merchant’s face, the lovely way she strummed her hair to take out the tangles, as if she were playing a harp, but all I could think about was ripping her clothes off. I did my best to steer my mind back to that cabin in the woods, where our children had braces, but I couldn’t stop thinking of the things I’d like to do to her. I felt tainted, polluted. My parents’ voices floated down the hall. At one point I must have drifted half-asleep because I imagined that Phoebe had me in her mouth and that I looked up and saw Jules watching us from behind a tree, his creepy eye shining in the dark.

I sat up in bed. The cicadas seemed quieter than usual, and as I listened more closely their sound seemed to transform itself into Errol Errol Errol. I slipped on my shorts, then creaked downstairs toward the front door. The house was as still as I’d ever felt it. I unlocked the front door and stepped outside to the sidewalk. The streetlights were on, and the branches of the trees drooped with bugs, glittering where the light caught them, like clusters of stars. Above the trees the real stars shone weakly in the sky, but the constellations seemed new and unfamiliar. I could not find the Big Dipper, or Orion, or even the North Star. I’d felt real homesickness before, when my parents sent me to camp in Maine one summer, and it was a longing so bad I felt like a genie might actually appear and whisk me home again; but now I was home and felt the same ghostly longing. All around me the trees seemed alive, chanting my name and turning it strange. I checked the freckles on my arms, to reassure myself, but in the dim glow of the streetlamp they seemed less ugly, as if they’d started to fade.

* * *

The next day was so muggy no one ventured outside but kids. Crawford and Stefano stopped by in their bathing suits, but I lied about having a dentist’s appointment and watched them drip off in the direction of the Giordanos’ pool before heading out on my bike. I rode through the deserted neighborhood, not sure where I was going until I got there. Phoebe Merchant always practiced on the same tennis court, number 14. There was a spot on the wooded hill behind the club where Stefano and I sometimes hid inside the leafy cave of a willow, watching the ball machine fire shots at her while she chased them down. Ordinarily you could hear the fump-pok of balls being spit out and hit, echoing like a heartbeat through the woods, but it was noon and the trees were so loud with the throb of cicadas that she seemed from my cave not to make any noise at all. It was like watching a dream. Her brown legs were slick with sweat, glistening in the sun, and her skirt flapped up when she turned her hips to swing, revealing a flash of pink. Her hair, done up in a braid, whipped her back.

She shanked a ball off the rim of her racket and it flew backward over the fence, plopping in the ivy several yards from me. I ducked out of the willow, quietly, and picked up the tennis ball. I had an erection that felt like a wound. When the machine stopped, Phoebe Merchant scraped open the gate and began to search the ivy behind the tennis court before noticing me. She jumped. Then she recovered just as quickly, grinning in that crooked way.

“Errol Redfield,” she said. “Is that you?”

I shook my head. She laughed.

“Well, if you’re not Errol Redfield, then who are you?”

“I don’t know.”

She glanced at the tennis ball, which I was holding in front of my crotch. She stopped smiling. Her shirt was soaked with sweat, and I could see the black butterfly of her bra showing through it. She smelled pleasant and unpleasant at the same time, like the inside of a pumpkin.

“Were you spying on me?” Phoebe Merchant said darkly.

“No,” I said.

“You know what I do to boys who spy on me, don’t you?”

I was too parched to speak. She glanced over her shoulder, at the empty court behind her.

“I’ll let you off easy this time,” she said, as if she were doing me a favor. “Hand me the tennis ball, and I’ll spare your life.”

I shook my head. This seemed to surprise her. On a low leaf of the willow, a green cicada was growing straight out of its shell like a sprout from a seed. Even its wings looked like petals. When I looked back, Phoebe Merchant’s face had changed. She was breathing through her mouth. She twined one leg behind the other, so that her Tretorns were on the wrong sides of each other. I felt like I was watching from high above.

“I’ll just have to grab it myself then, I guess, won’t I?”

She took a step forward. My heart beat against my chest. My hard-on was beating too. It didn’t seem strange to have two hearts. Anything might happen—was happening. Phoebe Merchant reached down for the tennis ball very slowly, creakingly slow, as if she were moving in outer space. She stopped an inch from the tennis ball, her fingers trembling. The trees screamed all around us. She tried to snatch the ball, but I dropped it and stepped into her hand and her eyes widened, as if she’d believed it was all pretend. I touched her hand, my heart beating against her fingers. She started to move and I helped her, squeezing her more tightly so that she was clutching me through my shorts, sliding her hand up and down the way I touched myself at night. When she tore her hand away I realized I’d been hurting her. She’d been trying to get loose. She stepped backward and almost tripped, breathing hard enough that I could see her braces. Her eyes were damp.

“Are you okay?”

I took a step toward her and she flinched, baring her teeth. A tiny rubber band stretched between her jaws.

I ran off and found my bike by the parking lot and steered it out to the road. The air was thick with the smell of rain. People passed me on the sidewalk but I kept my eyes on the street, imagining they’d flinch away from me the way Phoebe Merchant had. Thunder rolled in the distance. I stood up on the pedals, pumping like crazy, the bike swaying beneath me.

I got to the Jenningses’ driveway and skidded to a stop. Jules was out front mowing the lawn, a sulk of boredom on his face. He wasn’t wearing a shirt, and his bony back was so drenched it looked like he’d been swimming. An unlit cigarette dangled from his mouth. He reached the far end of the overgrown lawn and wheelied the mower around and shoved it into some extra-tall weeds, where it guttered to a stop.

My eyes stung. I ditched my bike and went after him. He spotted me and took off across the lawn but then lost his shoe in a pile of grass cuttings, and I tackled him near a hedge of boxwoods. “What did you do to me?” I said, straddling him.

“What are you talking about?”

“In the root cellar!”

“Nothing,” Jules gasped. “I was just messing with you.”

A raindrop, thick as a loogie, splashed my head. I dug my fingers into his wrists.

“How did your father die?”

“He didn’t,” Jules said. “He lives in Berkeley. In an apartment. With his research assistant.” His eyes narrowed, and the vicious pleasure in them startled me. “Now they can fuck as much as they want.”

He looked at me, his lip trembling, and the viciousness faded. Up close, his pupil looked less like a stopped clock and more like a tiny black keyhole. Strange as it sounds, this may have been the first time I really saw anyone’s face. It was a young face, a scared one, and I understood why someone might want there to be more than one world. I shut my eyes for a moment.

“Boys!”

I scrambled to my feet. Mrs. Jennings stood in the doorway, wearing pajamas in the middle of the day. Her eyes were puffy, and instead of boots she had on some blue cloth slippers she must have gotten on an overseas flight. My mother had a pair just like them.

“Were you fighting?” Mrs. Jennings said.

“No,” Jules said. His face was flushed.

“Let’s not give them any more to gossip about. The neighbors think we’re weird enough as it is.”

I wondered if she was talking about my mom. It was raining now for real, stirring the cicadas into a kind of frenzy, as if they could sense that their days were numbered. I wanted, suddenly, to defend my mother.

“Will those dumb bugs ever shut up?” Mrs. Jennings said.

* * *

We were all relieved when the cicadas began to disappear. They dripped from the trees like snow and carpeted the sidewalks. Suddenly we could hear birds singing again. We could hear the scrape of our own shoes. We could hear the hum of the electrical wires festooning our street. We could hear the sprinklers chk-chk-chking on the lawns, the shrieks and splashes of swimming pools, the kurraaang of basketballs missing their baskets. We could hear snatches of music drifting on the breeze. We could hear the planes buzzing overhead and the bees buzzing in the flowers. We talked normally, without shouting, and our voices seemed like new and powerful instruments. For a day or two, we listened to whatever anyone had to say. My dad whispered in my mother’s ear at dinner, and it was like I could hear the corny things he was saying, so badly did I want them to be true. Out with you, my mother said to us, giggling, No kids allowed, and we climbed the trees and walked barefoot in the grass, and it seemed like we might stay outside forever.

Product Details

- Publisher: Scribner (February 20, 2018)

- Length: 240 pages

- ISBN13: 9781501147814

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

"Last Day on Earth is a direct hit to the solar plexus that manages to be completely entertaining. The characters in this collection are both familiar and surprising, and the grace Puchner lends to their struggles and hopes is profound. That he also writes sentences, paragraphs, pages that are funny, propulsive and true is nearly annoying, but this kind of consummate skill can only result in gleeful admiration. I can’t remember the last time I enjoyed a collection more. There is not a false note in this book.”

– Cynthia D’Aprix Sweeney, author of The Nest

“Pushing the bounds of the Richter Scale, the nine stories in Last Day on Earth are going to shake up the story world."

– Adam Johnson, author of Fortune Smiles

“Eric Puchner is an alchemist who captures the joy and danger in everyday life and, with precision, humor, and empathy, turns these moments into gold. These stories allow us to look at our own lives more closely and with more courage and understanding--a poignant and unforgettable collection from a great storyteller.”

– Yiyun Li, author of Dear Friend, From My Life I Write to You in Your Life

"A skewed and fantastic vision of the world."

– Kirkus, STARRED review

"Ray Bradbury meets Tom Perrotta in this new collection which blends science fiction with all-too-real suburban horrors."

– Publishers Weekly

“Puchner deftly captures the nuances of human interactions, and while characters in the nine tales often stumble at the crossroads, there remains the hope that one day they may find the answers they seek.”

– Booklist

"Regardless of how modern our times might be, there's always a generation that's attempting to come of age in suburban America... these stories get right to the heart of what it feels like to be a not-quite adult."

– Newsweek

"Well-crafted... memorable portraits of suburban angst... a unique take on themes of family and belonging."

– Michael Magras, Houston Chronicle

"Puchner shows us the many complicated facets of family and domestic life, of adolescence, parenthood, and coming of age, through a variety of highly compelling lenses."

– Buzzfeed

“Puchner’s affecting collection explores the endings of things — relationships, childhood, the illusion that one is a morally upstanding person — as well as what endures for the sympathetic characters in these nine stories… top-notch realistic fiction, sensitive to the complexities of more or less ordinary lives.”

– Polly Rosenwaike, San Francisco Chronicle

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Last Day on Earth Trade Paperback 9781501147814

- Author Photo (jpg): Eric Puchner Photograph by Gordon Noel(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit