Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

Table of Contents

About The Book

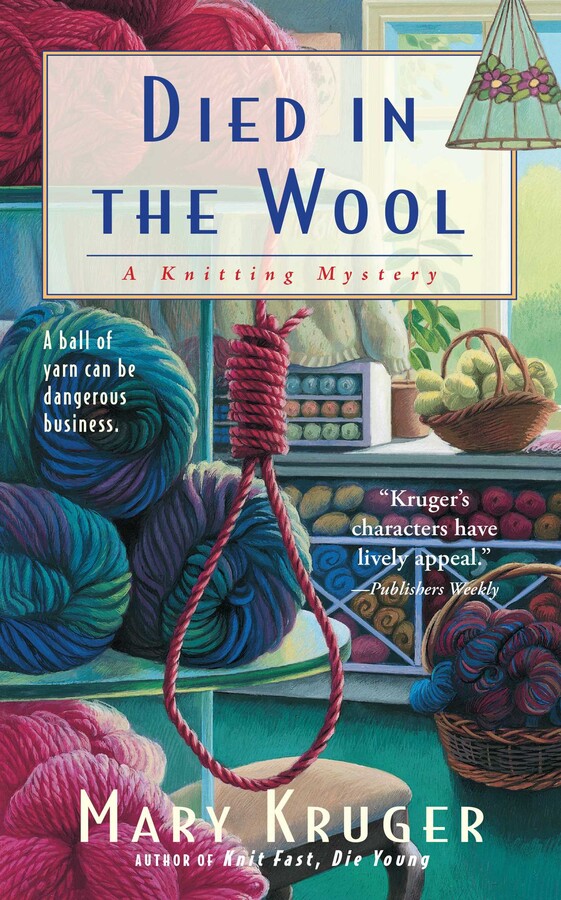

The first novel in Mary Kruger’s “lively” (Publishers Weekly) knitting-themed mystery series set in coastal Massachusetts.

Ariadne Evans is the proud owner of her very own knitting shop. And she’s just got herself in a stitch.

When Ariadne enters her knitting store one day to find longtime customer Edith Perry strangled to death with homespun yarn, she fears her life is about to come undone—again, since she’s still getting over a divorce. Her worries increase when she’s questioned by detective Joshua Pierce, who may or may not have designs on her. While Josh pieces together the details of the crime, clues about Ariadne’s ties to Miss Perry come to light...and a bizarre pattern unfolds. Now it’s up to Ariadne to do some sleuthing of her own. Can she untangle the investigation without getting snarled up into too much trouble? That depends on whether the killer is as crafty as she is...

Ariadne Evans is the proud owner of her very own knitting shop. And she’s just got herself in a stitch.

When Ariadne enters her knitting store one day to find longtime customer Edith Perry strangled to death with homespun yarn, she fears her life is about to come undone—again, since she’s still getting over a divorce. Her worries increase when she’s questioned by detective Joshua Pierce, who may or may not have designs on her. While Josh pieces together the details of the crime, clues about Ariadne’s ties to Miss Perry come to light...and a bizarre pattern unfolds. Now it’s up to Ariadne to do some sleuthing of her own. Can she untangle the investigation without getting snarled up into too much trouble? That depends on whether the killer is as crafty as she is...

Excerpt

Died in the Wool

one

LATER, ARIADNE WOULD BE APPALLED that her first reaction at seeing Edith Perry’s body sprawled on the floor of her shop, a tangle of yarn around her throat, was that Edith had finally chosen good yarn. She would be horrified that she had wished the yarn wasn’t one of her favorites. It was shock, she knew: finding a dead body always had that effect.

After her initial reaction she stood, shocked in place, then kneeled beside the counter. “Omigod. Omigod,” she gasped. A purple wool homespun yarn was tangled about Edith’s neck and tied in back to two sticks in a crude, but effective, garrote. “Omigod, Edith, wake up.” She took the woman’s wrist in her hand, hoping, praying that she might be alive. There was no pulse. Instead, Edith’s hand was limp and cool. “No, Edith, not in my shop,” Ari said, hearing herself for the first time. Dear God. There was a dead body in her shop.

It couldn’t be real. Until this moment her morning had been unremarkable. She’d yawned over the newspaper, tussled with her young daughter, Megan, about what to wear to school, and fielded a call from her friend Diane, who rose before the birds. Ari was a night person who moved in slow motion in the mornings. It was only as she took her usual brisk walk from home through the center of Freeport to her shop that she came fully awake. Only then did she become excited about the day ahead, her mind teeming with ideas for new sweaters, scarves, hats. Finding someone murdered in her shop changed all that.

She looked up. The shop itself seemed normal. The plate glass windows on the front and side of her building still filtered the bright September sun through the gray coating designed to keep the light from fading the yarn. The high shelves on the inside wall still held diamond-shaped bins filled with various yarns: Heilo yarn from Norway; Lopi, made from the wool of Icelandic sheep; fisherman yarn from Ireland. So did the low shelves under the side windows; so did the waist-high counter in the middle of the shop, with its colorful knitted goods displayed on top. Soothed as she always was by the sight of her yarns and the possibilities they presented, she looked back down. Edith’s body was still there, between the counter and the wall, sprawled in the careless abandon of death.

Calm, Ari, she told herself as she rose. Odd how her mind seemed to have separated from the rest of her, viewing what was happening with detachment. Again she looked at her yarn, and suddenly stopped, counting. One ball of the purple yarn was missing. Only a small amount was twined around Edith’s neck. The murderer had, at some point, taken one of the balls of yarn.

Ari stumbled as she crossed the room to the phone. She had to call 911. After she reported the murder and the police assured her they would arrive shortly, she sat at the old wooden desk in her office, elbows resting on the tidy surface, and put her fisted hands to her eyes, trying to control her shaking.

“Ariadne,” a voice called from the shop’s front door, sharp and concerned. “Ari! Where are you?”

Ariadne straightened, both relieved and dismayed, and rose to leave her sanctuary. “Here, Aunt Laura.”

“What happened? Was it a robbery?” Laura Sheehan, eyes sharp, her trim, athletic body tense, rushed toward her. Her polo shirt wasn’t quite tucked into her jeans, which was unusual for Laura. “There’s no sign of a break-in—oh.” She looked down in disbelief at the body behind the counter. “Edith? Edith Perry?”

Ari leaned her head against the door frame. “Laura, what are you doing here?”

“I heard the call on my police radio. They didn’t say anything about a body.”

“And you decided to come here?”

“You might have been in danger.”

“For God’s sake.”

“I did take that self-defense class. I must say, this is a bit of a sticky wicket, isn’t it?”

Ari let out a breath. “You’ve been reading English mysteries again.”

“No, Ed McBain. This could be a good cozy mystery, though. The Body in the Yarn Shop.” She shook her head. “No. Not a good title.”

“Laura, please.”

Laura’s bemused expression faded. “I’m sorry.” She stood beside her niece. “Poor Edith,” she said, and then slung her arm around Ari’s shoulders. “And poor you.”

Ari closed her eyes, suddenly tired. “I know. Oh—the police.” She crossed to the door as an officer rapped sharply against the glass, and opened it for him.

Much later, she would think that finding the body was the easy part.

Joshua Pierce, only recently hired as detective on Freeport’s small police force, stared down at the body in the shop. Well. This was different. In Boston he’d handled drive-by shootings and the occasional domestic murder, but never anything like this. He knew where to start, he thought, glancing over at the shop’s owner, who was perched on a high stool behind a counter for the cash register. Mrs. Evans was going to come in for some close questioning.

Hands tucked into the pockets of his chinos, he studied the body impassively. It wasn’t that the sight of death didn’t bother him; it did. He’d learned long ago to tuck his emotions away. He felt nothing but professional interest now as he went about his work. The victim had been a woman somewhere in her sixties, or perhaps early seventies. It was hard to tell because in spite of her short white hair, her face was relatively unlined and her body was compact and firm. Being new to Freeport, he knew nothing about her, but that was an advantage. He’d come to the investigation without any preconceptions.

Around him, the crime scene investigators were at work. The medical examiner had come and gone, the district attorney was near the door with the chief of police, and the crime scene technicians were at work, dusting for fingerprints and packing up the remainder of the yarn used for the murder in paper evidence bags. Other technicians were vacuuming the floor for fibers and other evidence. The police photographer had taken many pictures, and Josh himself had drawn a careful sketch of the scene. This part of his investigation was done. It was time to move on to the next phase.

“Mrs. Evans?” He held out his hand. “Joshua Pierce.”

“I didn’t kill her,” she said swiftly.

“I didn’t say you did, ma’am.” Interesting that she’d say that right away, he thought. “Is there somewhere we can talk?”

She stared at him for a moment, then climbed down from the stool. “The back room’s the best place,” she said, leading him through a doorway at the back of the retail area and into a long, narrow room with a bolted door in the far wall. The back entrance, he assumed, making a careful note of it. They still didn’t know how the victim, or the murderer, had gotten into the shop.

“Would you like coffee?” Mrs. Evans went on, crossing to a counter against the wall. “I just made it. I was thinking of sending out for doughnuts—oh.” She scrunched her eyes shut. “Tell me I didn’t say that.”

“A cop’s usual snack?” He smiled slightly. “No, don’t bother on my account. Coffee’s fine.”

She nodded and poured coffee into two mugs, giving him a chance to study her. In spite of what had had happened, she looked cool and neat, in tan linen pants and a crisp white blouse. Her hair, a light blondish brown, was long and held back from her face with clips. Only her eyes betrayed her agitation, he thought as she brought the cups over to the old green Formica-topped table. Rather nice hazel eyes, he noted.

“Now, Mrs. Evans,” he began.

“Ms.”

He looked up from his notebook. “Ms.? Okay.”

“I’m divorced,” she added defiantly.

He flipped his pen back and forth between his index and middle fingers. “Then Evans is your maiden name?”

“No. Jorgensen. Ariadne Jorgensen. A mouthful, isn’t it?”

He frowned. “I thought Arachne was the goddess of spinning.”

She blinked. “Well, yes, but my father vetoed that name, thank God. Ariadne was a compromise. She’s the one who spun a thread to lead Theseus out of the labyrinth, in Greek mythology. It sort of fits for the shop.”

“Mmm-hmm.” He glanced down at his notebook, though he didn’t need to refresh his memory. “Could you tell me how you found the body?”

“I already answered that.”

“I’d like to go over it again.”

She looked at him warily. “All right. I looked on the floor, and there she was.”

“Just like that?”

“Well, no. She looked the same as she does now, except that I felt for a pulse. I realize I tampered with a crime scene.”

“Mrs. Evans—”

“Ms.”

“Ms. Evans, did you want to see if she was still alive?”

She thought about that for a moment. “No, I think I knew she was dead right away. But I still wanted to see if I could help her. Even if I didn’t like her.”

He gave her a long look. “Why not?”

She bit her lip. “It wasn’t personal. No one liked her very much. It’s not that she’s a terrible person—was a terrible person. Like doing mean things to people, the way victims on TV mysteries do.”

“Real crimes aren’t usually like TV crimes.”

“No.” Ms. Evans glanced away, into her shop. “The only person I know for certain she had problems with was her son. They fought about something, so she cut him out of her will. Other than that, I don’t think she ever did anything terrible. She just liked getting her own way.”

He leaned back in his chair. “You don’t know what they fought about?”

“No one does. So far as I know, she hasn’t talked to him since. He lives in Amherst and doesn’t have a key to this place. How could he have done it?”

“Why didn’t you like her?”

Ms. Evans took a deep breath. “No real reason. She just wasn’t a very pleasant person. She never smiled and didn’t talk much, and, oh, she was always trying to get things cheap.”

That made him look up. “Such as your stock?”

She nodded. “And my designs. Of course, she never did. If she’d been nicer I might have given her a discount now and then, but she was usually rude about it.”

“And that bothered you?”

“Of course it did, but not enough for me to kill her.”

He nodded. “Tell me how you found her,” he said again.

“Well.” Her hands rubbed together. “I came in early to do paperwork. I wish I had some knitting,” she added.

It was his turn to be surprised. “Why?”

“Because when I get nervous it soothes me.”

Nervousness could be a sign of innocence, he thought, especially in a case like this. It could also be a sign of an amateur’s guilt. Whoever had killed Edith had to have known her well. Strangling, especially in such a way, was an intimate crime. “Can’t help you there. Go on.”

“Well. It was—is—a beautiful morning. Most mornings I walk.”

“Where do you live?”

“Walnut Street. A few blocks away.” She gestured vaguely. “I was thinking how much I like this time of year.”

“All right. I’ll ask,” he said when she paused. “Because of the weather?”

“Oh, no. Well, yes, I do like the colors. A little like you.”

“What?” he said, startled.

“N-nothing.” She looked hastily away. “This time of year—yes, I like the colors, and the air, and—I’m babbling.” She took another deep breath and then went on, more composed. “This time of year, people start to think of making sweaters, so they come in.”

“Good for business, then.”

“Yes. In the summer, people want cottons or light yarns, but most crafters switch to cross-stitch or something cooler. In a couple of months, people will want supplies for afghans, and when we get the January freeze, we’ll do a good business in wool hats and mittens. Well. You don’t care about that.” She took a sip of her coffee. “I have paperwork to do. Bills to pay, stock to order, things like that. Do you know what I mean?”

Josh only nodded, and so she went on. “I love early mornings here, when I’m alone and I know I won’t be interrupted. I like to switch on the lights and just look at everything.” She smiled. “Ted—my ex—complained when I put in the Ott lights—”

“The what?”

“Oh, of course you wouldn’t know. Full-spectrum lamps, like daylight. They’re expensive, but they’re worth it for matching colors and shades. I just like to look at my yarns. All the skeins and twists and colors, and all the patterns and notions and needles. I love everything in my shop. There’s just so much possibility here.”

“So that’s what you did this morning?”

Her enthusiasm faded. “Not at first. I was really thinking about everything I have to do today when I went around the counter and found Edith.”

“So you were alone?” he said.

“Yes. We don’t open until ten.”

“But you came in early.”

“Yes.” Her hands rubbed together again. “I do, sometimes.”

“What time did you leave last night?”

“I’m not open on Mondays.” She paused. “When did she die?”

“We don’t know yet,” he said, though the medical examiner had given him a rough idea. Early morning, he’d said, somewhere between five and eight. Ms. Evans was definitely in contention as the culprit. “When were you in the shop last?”

“Saturday. I close at two. I stayed until around two-thirty to count the day’s receipts, clean up a little.”

“What kind?”

“Dusting and vacuuming.”

So any fingerprints and trace evidence would be new, he thought, and more likely to belong to the murderer. That was a break. “What about your employees?”

“Yes, one was supposed to come in at ten.”

“And she is?”

“Summer Foley. She’s worked here since I opened.”

“Does she have a key?”

“Yes. Oh, but she couldn’t have had anything to do with this.”

“How well did she know Mrs. Perry?”

Ms. Evans looked surprised. “Summer? I don’t know. She’s only a college student, Detective. She works part-time around her class schedule.”

That didn’t necessarily mean anything, but the age difference made it unlikely that the Foley girl had known the victim well. “Any idea where she might have been?”

“With her boyfriend, I imagine. They live together.”

“What about any other employees?”

“There’s one other girl, Kaitlyn Silveira. She used to be a student at RISD, so I hired her only for Saturdays.”

“The Rhode Island School of Design? Why isn’t she there anymore?”

“Money problems. She transferred to UMass Dartmouth,” she added.

“RISD is an expensive school.”

“Yes. It’s where I went. I wanted to—never mind.”

He sat back. “What?”

“It doesn’t matter, does it?”

“At this point, anything could.”

“That I wanted to be a designer in New York? How could that help?”

“I don’t know yet.”

She frowned at him. “How can you be so calm?”

“What do you mean?”

“Calm, cool, expressionless. How am I supposed to know what you’re thinking?”

He smiled. “You’re not. So you only have two employees?”

“Well, there’s my aunt Laura, but she doesn’t count.”

He consulted his notebook. “Laura Sheehan? She was here with you this morning, wasn’t she?”

“Yes.”

“Why doesn’t she count?”

“Because she wouldn’t do anything to hurt me.”

He gave her that level look again. “Does she have a key?”

“Laura? No. I know better than that.”

“Why?”

“Because then she’d be here at all hours.”

It was his turn to sigh. “I think you’d better explain.”

“Didn’t I? Oh, no, I didn’t. Laura loves yarn, you see. The shop is like a plaything to her.”

“I see. Who else has a key?” he asked,

“Only my mother. Detective Pierce, neither of them could have killed Edith Perry. I’d swear to that,” she said, and as she did so apparently realized the implications of all that she’d said. “Omigod. I’m a suspect, aren’t I?”

“It’s early for that.”

“Is it?” Something in her face changed. “I don’t think I want to answer any more questions,” she said, rising.

He stayed seated. “If you haven’t done anything, you don’t have anything to fear.”

“You know better than that,” she chided him, and rose. “I’m calling my ex-husband.”

“Why?”

“He’s an attorney.”

Josh looked at her and got up at last. “All right,” he said finally, and shut his notebook. “This should be enough to start with. I’ll want to talk with you again.”

She nodded. “With Ted along,” she said, her fingers gripping the edge of the table.

Count on it, Josh thought as he left the back room. Whether she had her lawyer with her or not, Ms. Evans had some questions to answer. At the moment she was his prime, and only, suspect.

“Yes, I know this is a crime scene,” an irritated voice said from outside sometime later. “I’m Mrs. Evans’s attorney.”

Ari rolled her eyes and got up from the office chair, where she’d been slumped for nearly an hour. Mrs. Evans, just as though they were still married, she thought. “Ted,” she said from the office doorway.

Her ex-husband stood just outside the door of the shop, glaring pugnaciously at the policeman who was guarding it. “Ari, what the hell have you gotten yourself into now?”

“He’s my lawyer,” she said quietly to Detective Pierce, who was looking at Ted with the same level look he’d used on her.

Ted and this detective were so different, she thought. It wasn’t just that Ted was short, in comparison to the taller and rangier detective. It wasn’t anything about his appearance, though his suit, made by an Italian designer, was a contrast to Detective Pierce’s off-the-rack tweed sport coat. The real difference was attitude: It was Ted’s belligerence, stemming from his lack of stature, among other things, that stood out against Detective Pierce’s laid-back watchfulness. Yet right now Ted was the person she wanted on her side.

“Ariadne,” Ted said as he strode past the policeman to her. “Are you all right?”

“Of course I am.” She stepped out of the office, making a wide circle past the point where Edith’s body, now removed from the shop, had lain. The surfaces of the counter were coated with the dreaded black fingerprint powder. “I’m glad you’re here.”

Ted looked past her, and she realized he was frowning at Josh. “Is she free to go?” he demanded.

“Yes.” By contrast, Detective Pierce’s voice was calm. “We’re not holding her.”

“Did you read her her rights?”

“No. She’s not under arrest.”

Ted glared at him, so obviously ready to erupt that Ari stepped in. “Please let me know when you’re done here,” she said.

Detective Pierce nodded. “You’ll be hearing from us, Ms. Evans.”

“You’ll be hearing from me,” Ted retorted.

“Sure. Ms. Evans, I’ll need your key.”

Ari stared at him in blank dismay as she took her key ring out of her pocketbook. “My house key’s on it,” she said, “and my Shaw’s discount card.”

“For God’s sake, Ariadne, you won’t be going to the supermarket today,” Ted said impatiently.

“They have a special on chicken—no, I won’t be, will I?”

“Damn straight. Just give him the key to the shop.” He turned to the detective. “Can we go?”

“Sure,” Detective Pierce said again. “Just stay somewhere where we can reach you, Ms. Evans.”

“You have my cell phone number,” she said, as Ted pulled her toward the door. “Be careful with my yarn!”

“Your yarn,” Ted grumbled, and pushed his way out of the shop, leaving Ari to trail behind him, and abandoning her to the questions of curious bystanders and reporters alike. Without looking at her, he strode toward the parking lot across the street and wrenched open the door of his BMW, all the time muttering to himself. Ari knew better than to ask him what he was saying.

He had not, of course, been thoughtful enough to hold the passenger door open for her. Ari glanced at him as she climbed in, feeling her own temper rising. It had been a trying day, to put it mildly. “Would you drive by Marty’s first?” she asked, naming a local convenience store, as he roared out of the lot.

“Why?”

“I need some chocolate.”

“Chocolate!” he exploded. “You’re suspected of murder and you want candy?”

“Why not?” she shot back. “It’s better than drinking.”

That stopped him, as she’d known it would. Only for a moment, though. “What the hell have you gotten yourself into this time, Ariadne?”

“I didn’t get myself into anything,” she retorted. “I walked in and there she was.”

“Do you realize you’re the prime suspect right now?”

“I’m not stupid, Ted.”

“What did you say to him before you called me?”

“I’ll have to think about it to remember. Ted, it’s been an awful morning.”

“It’ll get worse if you get arrested.”

“Well, I don’t think I said anything damaging.” She paused. “I told him a lot of people didn’t like her.”

“Oh, great. Like you?”

“Well, yes.”

“Damn it, Ariadne!” He slammed his hand on the steering wheel. “Don’t you realize what you admitted?”

“He doesn’t know Edith was going to buy my building,” she shot back.

“He will soon.”

“He’ll find things out about Herb Perry and Eric, too.”

“They don’t have keys to the store.”

“They could have got in some other way.”

“How? And why?”

“I don’t know!”

“You’ve got a hell of a motive, Ari.”

“That Edith was going to raise my rent? Really, Ted.”

“It’ll interest them. So will the Drift Road development,” he went on. “But I forgot. That’s not something you’d want to think about, not with what it means for your friend.”

“Other people are affected by that, too.”

“No one else you care about.”

“Diane doesn’t have a key.”

“If it’s not you, it has to be someone.” He jolted to a stop in the small parking lot in front of the store. “Don’t take long.”

Without a word, Ari climbed out and disappeared into the store. A few minutes later she emerged carrying a large bag of M&M’s. She didn’t get back in the car right away, though, not with Ted in his current mood. For a moment she looked diagonally across the small nearby bridge that spanned the inlet from the bay. Everything appeared so normal, it was almost unreal. Already it looked like fall. The leaves of the maple trees that shaded the street were just a little crisp around the edges, and the sky was the electric blue peculiar to September. Too warm to be sweater weather yet, she thought, and shivered. After what had happened today, she wondered if it would ever be sweater weather again at Ariadne’s Web.

That afternoon, Diane Camacho looked around in blank horror at the disaster that once had been Ariadne’s Web. “My God, you should call the EPA to clean this place up.”

“I know.” Ari smiled wearily at Diane, who had been her friend since high school. “I’d read that fingerprint powder was hard to get off, but I never knew how hard.” She brushed a strand of hair off her face. “It clings to everything. I don’t know how I’ll get the shop clean.”

“We’ll work together. You’ve got some on your face.”

She grimaced. “Do I? Damn.”

Diane frowned, her hands on her hips. “All your beautiful yarn, Ari. Will insurance cover it?”

“The police were good about that. They put on rubber gloves and put it all in paper bags before they started fingerprinting.” Almost all, she amended to herself. It was going to be hard to tell Diane that one bin, particularly one section of the yarn, had received special treatment.

“We’ll need some big aprons before we get started. Does anyone sell them anymore?”

“Laura told me she had some smocks.”

“They should do.” She frowned. “All this because of Edith Perry. Why her?”

Ari picked up a damp cloth and ran it across a countertop. “I don’t know. A lot of people didn’t like her.”

“That’s the trouble. She sure spread it around equally, didn’t she? Ari?”

Ari turned. “What?”

“Have you thought that maybe you’re the real target?”

“What? Why?”

“Because of where she was killed. Maybe someone wants to frame you.”

“Oh, get real. No one hates me that much. Not even Ted.”

“Ted likes you too much.”

“He’s crazy, Di, but not like this.” Now she frowned. “Of course, I’ve wondered why it happened here.”

“You’ve got to admit there are a lot of weapons in a knitting shop.”

Ari stiffened. The cause of death was common knowledge. What wasn’t, was which yarn had been used, or exactly how. “Such as?”

Diane grinned, the unholy smile that Ari had learned long ago meant trouble. “The killer had to be pretty sharp.”

“What?”

“It’s the best place to needle someone.”

“That’s not funny, Di.”

Her grin broadened, in spite of, or maybe because of, Ari’s reaction. “Yeah, but you got the point.”

“Di—”

“I hope the police do, or they’ll get all tangled up.”

“You and I both are tangled up,” Ari snapped.

Diane had been looking around as if in search of another source of puns, but at that she looked at Ari. “What do you mean? I had nothing to do with it.”

“I’m afraid you did.” Ari took a deep breath. “She was strangled with your yarn.”

one

LATER, ARIADNE WOULD BE APPALLED that her first reaction at seeing Edith Perry’s body sprawled on the floor of her shop, a tangle of yarn around her throat, was that Edith had finally chosen good yarn. She would be horrified that she had wished the yarn wasn’t one of her favorites. It was shock, she knew: finding a dead body always had that effect.

After her initial reaction she stood, shocked in place, then kneeled beside the counter. “Omigod. Omigod,” she gasped. A purple wool homespun yarn was tangled about Edith’s neck and tied in back to two sticks in a crude, but effective, garrote. “Omigod, Edith, wake up.” She took the woman’s wrist in her hand, hoping, praying that she might be alive. There was no pulse. Instead, Edith’s hand was limp and cool. “No, Edith, not in my shop,” Ari said, hearing herself for the first time. Dear God. There was a dead body in her shop.

It couldn’t be real. Until this moment her morning had been unremarkable. She’d yawned over the newspaper, tussled with her young daughter, Megan, about what to wear to school, and fielded a call from her friend Diane, who rose before the birds. Ari was a night person who moved in slow motion in the mornings. It was only as she took her usual brisk walk from home through the center of Freeport to her shop that she came fully awake. Only then did she become excited about the day ahead, her mind teeming with ideas for new sweaters, scarves, hats. Finding someone murdered in her shop changed all that.

She looked up. The shop itself seemed normal. The plate glass windows on the front and side of her building still filtered the bright September sun through the gray coating designed to keep the light from fading the yarn. The high shelves on the inside wall still held diamond-shaped bins filled with various yarns: Heilo yarn from Norway; Lopi, made from the wool of Icelandic sheep; fisherman yarn from Ireland. So did the low shelves under the side windows; so did the waist-high counter in the middle of the shop, with its colorful knitted goods displayed on top. Soothed as she always was by the sight of her yarns and the possibilities they presented, she looked back down. Edith’s body was still there, between the counter and the wall, sprawled in the careless abandon of death.

Calm, Ari, she told herself as she rose. Odd how her mind seemed to have separated from the rest of her, viewing what was happening with detachment. Again she looked at her yarn, and suddenly stopped, counting. One ball of the purple yarn was missing. Only a small amount was twined around Edith’s neck. The murderer had, at some point, taken one of the balls of yarn.

Ari stumbled as she crossed the room to the phone. She had to call 911. After she reported the murder and the police assured her they would arrive shortly, she sat at the old wooden desk in her office, elbows resting on the tidy surface, and put her fisted hands to her eyes, trying to control her shaking.

“Ariadne,” a voice called from the shop’s front door, sharp and concerned. “Ari! Where are you?”

Ariadne straightened, both relieved and dismayed, and rose to leave her sanctuary. “Here, Aunt Laura.”

“What happened? Was it a robbery?” Laura Sheehan, eyes sharp, her trim, athletic body tense, rushed toward her. Her polo shirt wasn’t quite tucked into her jeans, which was unusual for Laura. “There’s no sign of a break-in—oh.” She looked down in disbelief at the body behind the counter. “Edith? Edith Perry?”

Ari leaned her head against the door frame. “Laura, what are you doing here?”

“I heard the call on my police radio. They didn’t say anything about a body.”

“And you decided to come here?”

“You might have been in danger.”

“For God’s sake.”

“I did take that self-defense class. I must say, this is a bit of a sticky wicket, isn’t it?”

Ari let out a breath. “You’ve been reading English mysteries again.”

“No, Ed McBain. This could be a good cozy mystery, though. The Body in the Yarn Shop.” She shook her head. “No. Not a good title.”

“Laura, please.”

Laura’s bemused expression faded. “I’m sorry.” She stood beside her niece. “Poor Edith,” she said, and then slung her arm around Ari’s shoulders. “And poor you.”

Ari closed her eyes, suddenly tired. “I know. Oh—the police.” She crossed to the door as an officer rapped sharply against the glass, and opened it for him.

Much later, she would think that finding the body was the easy part.

Joshua Pierce, only recently hired as detective on Freeport’s small police force, stared down at the body in the shop. Well. This was different. In Boston he’d handled drive-by shootings and the occasional domestic murder, but never anything like this. He knew where to start, he thought, glancing over at the shop’s owner, who was perched on a high stool behind a counter for the cash register. Mrs. Evans was going to come in for some close questioning.

Hands tucked into the pockets of his chinos, he studied the body impassively. It wasn’t that the sight of death didn’t bother him; it did. He’d learned long ago to tuck his emotions away. He felt nothing but professional interest now as he went about his work. The victim had been a woman somewhere in her sixties, or perhaps early seventies. It was hard to tell because in spite of her short white hair, her face was relatively unlined and her body was compact and firm. Being new to Freeport, he knew nothing about her, but that was an advantage. He’d come to the investigation without any preconceptions.

Around him, the crime scene investigators were at work. The medical examiner had come and gone, the district attorney was near the door with the chief of police, and the crime scene technicians were at work, dusting for fingerprints and packing up the remainder of the yarn used for the murder in paper evidence bags. Other technicians were vacuuming the floor for fibers and other evidence. The police photographer had taken many pictures, and Josh himself had drawn a careful sketch of the scene. This part of his investigation was done. It was time to move on to the next phase.

“Mrs. Evans?” He held out his hand. “Joshua Pierce.”

“I didn’t kill her,” she said swiftly.

“I didn’t say you did, ma’am.” Interesting that she’d say that right away, he thought. “Is there somewhere we can talk?”

She stared at him for a moment, then climbed down from the stool. “The back room’s the best place,” she said, leading him through a doorway at the back of the retail area and into a long, narrow room with a bolted door in the far wall. The back entrance, he assumed, making a careful note of it. They still didn’t know how the victim, or the murderer, had gotten into the shop.

“Would you like coffee?” Mrs. Evans went on, crossing to a counter against the wall. “I just made it. I was thinking of sending out for doughnuts—oh.” She scrunched her eyes shut. “Tell me I didn’t say that.”

“A cop’s usual snack?” He smiled slightly. “No, don’t bother on my account. Coffee’s fine.”

She nodded and poured coffee into two mugs, giving him a chance to study her. In spite of what had had happened, she looked cool and neat, in tan linen pants and a crisp white blouse. Her hair, a light blondish brown, was long and held back from her face with clips. Only her eyes betrayed her agitation, he thought as she brought the cups over to the old green Formica-topped table. Rather nice hazel eyes, he noted.

“Now, Mrs. Evans,” he began.

“Ms.”

He looked up from his notebook. “Ms.? Okay.”

“I’m divorced,” she added defiantly.

He flipped his pen back and forth between his index and middle fingers. “Then Evans is your maiden name?”

“No. Jorgensen. Ariadne Jorgensen. A mouthful, isn’t it?”

He frowned. “I thought Arachne was the goddess of spinning.”

She blinked. “Well, yes, but my father vetoed that name, thank God. Ariadne was a compromise. She’s the one who spun a thread to lead Theseus out of the labyrinth, in Greek mythology. It sort of fits for the shop.”

“Mmm-hmm.” He glanced down at his notebook, though he didn’t need to refresh his memory. “Could you tell me how you found the body?”

“I already answered that.”

“I’d like to go over it again.”

She looked at him warily. “All right. I looked on the floor, and there she was.”

“Just like that?”

“Well, no. She looked the same as she does now, except that I felt for a pulse. I realize I tampered with a crime scene.”

“Mrs. Evans—”

“Ms.”

“Ms. Evans, did you want to see if she was still alive?”

She thought about that for a moment. “No, I think I knew she was dead right away. But I still wanted to see if I could help her. Even if I didn’t like her.”

He gave her a long look. “Why not?”

She bit her lip. “It wasn’t personal. No one liked her very much. It’s not that she’s a terrible person—was a terrible person. Like doing mean things to people, the way victims on TV mysteries do.”

“Real crimes aren’t usually like TV crimes.”

“No.” Ms. Evans glanced away, into her shop. “The only person I know for certain she had problems with was her son. They fought about something, so she cut him out of her will. Other than that, I don’t think she ever did anything terrible. She just liked getting her own way.”

He leaned back in his chair. “You don’t know what they fought about?”

“No one does. So far as I know, she hasn’t talked to him since. He lives in Amherst and doesn’t have a key to this place. How could he have done it?”

“Why didn’t you like her?”

Ms. Evans took a deep breath. “No real reason. She just wasn’t a very pleasant person. She never smiled and didn’t talk much, and, oh, she was always trying to get things cheap.”

That made him look up. “Such as your stock?”

She nodded. “And my designs. Of course, she never did. If she’d been nicer I might have given her a discount now and then, but she was usually rude about it.”

“And that bothered you?”

“Of course it did, but not enough for me to kill her.”

He nodded. “Tell me how you found her,” he said again.

“Well.” Her hands rubbed together. “I came in early to do paperwork. I wish I had some knitting,” she added.

It was his turn to be surprised. “Why?”

“Because when I get nervous it soothes me.”

Nervousness could be a sign of innocence, he thought, especially in a case like this. It could also be a sign of an amateur’s guilt. Whoever had killed Edith had to have known her well. Strangling, especially in such a way, was an intimate crime. “Can’t help you there. Go on.”

“Well. It was—is—a beautiful morning. Most mornings I walk.”

“Where do you live?”

“Walnut Street. A few blocks away.” She gestured vaguely. “I was thinking how much I like this time of year.”

“All right. I’ll ask,” he said when she paused. “Because of the weather?”

“Oh, no. Well, yes, I do like the colors. A little like you.”

“What?” he said, startled.

“N-nothing.” She looked hastily away. “This time of year—yes, I like the colors, and the air, and—I’m babbling.” She took another deep breath and then went on, more composed. “This time of year, people start to think of making sweaters, so they come in.”

“Good for business, then.”

“Yes. In the summer, people want cottons or light yarns, but most crafters switch to cross-stitch or something cooler. In a couple of months, people will want supplies for afghans, and when we get the January freeze, we’ll do a good business in wool hats and mittens. Well. You don’t care about that.” She took a sip of her coffee. “I have paperwork to do. Bills to pay, stock to order, things like that. Do you know what I mean?”

Josh only nodded, and so she went on. “I love early mornings here, when I’m alone and I know I won’t be interrupted. I like to switch on the lights and just look at everything.” She smiled. “Ted—my ex—complained when I put in the Ott lights—”

“The what?”

“Oh, of course you wouldn’t know. Full-spectrum lamps, like daylight. They’re expensive, but they’re worth it for matching colors and shades. I just like to look at my yarns. All the skeins and twists and colors, and all the patterns and notions and needles. I love everything in my shop. There’s just so much possibility here.”

“So that’s what you did this morning?”

Her enthusiasm faded. “Not at first. I was really thinking about everything I have to do today when I went around the counter and found Edith.”

“So you were alone?” he said.

“Yes. We don’t open until ten.”

“But you came in early.”

“Yes.” Her hands rubbed together again. “I do, sometimes.”

“What time did you leave last night?”

“I’m not open on Mondays.” She paused. “When did she die?”

“We don’t know yet,” he said, though the medical examiner had given him a rough idea. Early morning, he’d said, somewhere between five and eight. Ms. Evans was definitely in contention as the culprit. “When were you in the shop last?”

“Saturday. I close at two. I stayed until around two-thirty to count the day’s receipts, clean up a little.”

“What kind?”

“Dusting and vacuuming.”

So any fingerprints and trace evidence would be new, he thought, and more likely to belong to the murderer. That was a break. “What about your employees?”

“Yes, one was supposed to come in at ten.”

“And she is?”

“Summer Foley. She’s worked here since I opened.”

“Does she have a key?”

“Yes. Oh, but she couldn’t have had anything to do with this.”

“How well did she know Mrs. Perry?”

Ms. Evans looked surprised. “Summer? I don’t know. She’s only a college student, Detective. She works part-time around her class schedule.”

That didn’t necessarily mean anything, but the age difference made it unlikely that the Foley girl had known the victim well. “Any idea where she might have been?”

“With her boyfriend, I imagine. They live together.”

“What about any other employees?”

“There’s one other girl, Kaitlyn Silveira. She used to be a student at RISD, so I hired her only for Saturdays.”

“The Rhode Island School of Design? Why isn’t she there anymore?”

“Money problems. She transferred to UMass Dartmouth,” she added.

“RISD is an expensive school.”

“Yes. It’s where I went. I wanted to—never mind.”

He sat back. “What?”

“It doesn’t matter, does it?”

“At this point, anything could.”

“That I wanted to be a designer in New York? How could that help?”

“I don’t know yet.”

She frowned at him. “How can you be so calm?”

“What do you mean?”

“Calm, cool, expressionless. How am I supposed to know what you’re thinking?”

He smiled. “You’re not. So you only have two employees?”

“Well, there’s my aunt Laura, but she doesn’t count.”

He consulted his notebook. “Laura Sheehan? She was here with you this morning, wasn’t she?”

“Yes.”

“Why doesn’t she count?”

“Because she wouldn’t do anything to hurt me.”

He gave her that level look again. “Does she have a key?”

“Laura? No. I know better than that.”

“Why?”

“Because then she’d be here at all hours.”

It was his turn to sigh. “I think you’d better explain.”

“Didn’t I? Oh, no, I didn’t. Laura loves yarn, you see. The shop is like a plaything to her.”

“I see. Who else has a key?” he asked,

“Only my mother. Detective Pierce, neither of them could have killed Edith Perry. I’d swear to that,” she said, and as she did so apparently realized the implications of all that she’d said. “Omigod. I’m a suspect, aren’t I?”

“It’s early for that.”

“Is it?” Something in her face changed. “I don’t think I want to answer any more questions,” she said, rising.

He stayed seated. “If you haven’t done anything, you don’t have anything to fear.”

“You know better than that,” she chided him, and rose. “I’m calling my ex-husband.”

“Why?”

“He’s an attorney.”

Josh looked at her and got up at last. “All right,” he said finally, and shut his notebook. “This should be enough to start with. I’ll want to talk with you again.”

She nodded. “With Ted along,” she said, her fingers gripping the edge of the table.

Count on it, Josh thought as he left the back room. Whether she had her lawyer with her or not, Ms. Evans had some questions to answer. At the moment she was his prime, and only, suspect.

“Yes, I know this is a crime scene,” an irritated voice said from outside sometime later. “I’m Mrs. Evans’s attorney.”

Ari rolled her eyes and got up from the office chair, where she’d been slumped for nearly an hour. Mrs. Evans, just as though they were still married, she thought. “Ted,” she said from the office doorway.

Her ex-husband stood just outside the door of the shop, glaring pugnaciously at the policeman who was guarding it. “Ari, what the hell have you gotten yourself into now?”

“He’s my lawyer,” she said quietly to Detective Pierce, who was looking at Ted with the same level look he’d used on her.

Ted and this detective were so different, she thought. It wasn’t just that Ted was short, in comparison to the taller and rangier detective. It wasn’t anything about his appearance, though his suit, made by an Italian designer, was a contrast to Detective Pierce’s off-the-rack tweed sport coat. The real difference was attitude: It was Ted’s belligerence, stemming from his lack of stature, among other things, that stood out against Detective Pierce’s laid-back watchfulness. Yet right now Ted was the person she wanted on her side.

“Ariadne,” Ted said as he strode past the policeman to her. “Are you all right?”

“Of course I am.” She stepped out of the office, making a wide circle past the point where Edith’s body, now removed from the shop, had lain. The surfaces of the counter were coated with the dreaded black fingerprint powder. “I’m glad you’re here.”

Ted looked past her, and she realized he was frowning at Josh. “Is she free to go?” he demanded.

“Yes.” By contrast, Detective Pierce’s voice was calm. “We’re not holding her.”

“Did you read her her rights?”

“No. She’s not under arrest.”

Ted glared at him, so obviously ready to erupt that Ari stepped in. “Please let me know when you’re done here,” she said.

Detective Pierce nodded. “You’ll be hearing from us, Ms. Evans.”

“You’ll be hearing from me,” Ted retorted.

“Sure. Ms. Evans, I’ll need your key.”

Ari stared at him in blank dismay as she took her key ring out of her pocketbook. “My house key’s on it,” she said, “and my Shaw’s discount card.”

“For God’s sake, Ariadne, you won’t be going to the supermarket today,” Ted said impatiently.

“They have a special on chicken—no, I won’t be, will I?”

“Damn straight. Just give him the key to the shop.” He turned to the detective. “Can we go?”

“Sure,” Detective Pierce said again. “Just stay somewhere where we can reach you, Ms. Evans.”

“You have my cell phone number,” she said, as Ted pulled her toward the door. “Be careful with my yarn!”

“Your yarn,” Ted grumbled, and pushed his way out of the shop, leaving Ari to trail behind him, and abandoning her to the questions of curious bystanders and reporters alike. Without looking at her, he strode toward the parking lot across the street and wrenched open the door of his BMW, all the time muttering to himself. Ari knew better than to ask him what he was saying.

He had not, of course, been thoughtful enough to hold the passenger door open for her. Ari glanced at him as she climbed in, feeling her own temper rising. It had been a trying day, to put it mildly. “Would you drive by Marty’s first?” she asked, naming a local convenience store, as he roared out of the lot.

“Why?”

“I need some chocolate.”

“Chocolate!” he exploded. “You’re suspected of murder and you want candy?”

“Why not?” she shot back. “It’s better than drinking.”

That stopped him, as she’d known it would. Only for a moment, though. “What the hell have you gotten yourself into this time, Ariadne?”

“I didn’t get myself into anything,” she retorted. “I walked in and there she was.”

“Do you realize you’re the prime suspect right now?”

“I’m not stupid, Ted.”

“What did you say to him before you called me?”

“I’ll have to think about it to remember. Ted, it’s been an awful morning.”

“It’ll get worse if you get arrested.”

“Well, I don’t think I said anything damaging.” She paused. “I told him a lot of people didn’t like her.”

“Oh, great. Like you?”

“Well, yes.”

“Damn it, Ariadne!” He slammed his hand on the steering wheel. “Don’t you realize what you admitted?”

“He doesn’t know Edith was going to buy my building,” she shot back.

“He will soon.”

“He’ll find things out about Herb Perry and Eric, too.”

“They don’t have keys to the store.”

“They could have got in some other way.”

“How? And why?”

“I don’t know!”

“You’ve got a hell of a motive, Ari.”

“That Edith was going to raise my rent? Really, Ted.”

“It’ll interest them. So will the Drift Road development,” he went on. “But I forgot. That’s not something you’d want to think about, not with what it means for your friend.”

“Other people are affected by that, too.”

“No one else you care about.”

“Diane doesn’t have a key.”

“If it’s not you, it has to be someone.” He jolted to a stop in the small parking lot in front of the store. “Don’t take long.”

Without a word, Ari climbed out and disappeared into the store. A few minutes later she emerged carrying a large bag of M&M’s. She didn’t get back in the car right away, though, not with Ted in his current mood. For a moment she looked diagonally across the small nearby bridge that spanned the inlet from the bay. Everything appeared so normal, it was almost unreal. Already it looked like fall. The leaves of the maple trees that shaded the street were just a little crisp around the edges, and the sky was the electric blue peculiar to September. Too warm to be sweater weather yet, she thought, and shivered. After what had happened today, she wondered if it would ever be sweater weather again at Ariadne’s Web.

That afternoon, Diane Camacho looked around in blank horror at the disaster that once had been Ariadne’s Web. “My God, you should call the EPA to clean this place up.”

“I know.” Ari smiled wearily at Diane, who had been her friend since high school. “I’d read that fingerprint powder was hard to get off, but I never knew how hard.” She brushed a strand of hair off her face. “It clings to everything. I don’t know how I’ll get the shop clean.”

“We’ll work together. You’ve got some on your face.”

She grimaced. “Do I? Damn.”

Diane frowned, her hands on her hips. “All your beautiful yarn, Ari. Will insurance cover it?”

“The police were good about that. They put on rubber gloves and put it all in paper bags before they started fingerprinting.” Almost all, she amended to herself. It was going to be hard to tell Diane that one bin, particularly one section of the yarn, had received special treatment.

“We’ll need some big aprons before we get started. Does anyone sell them anymore?”

“Laura told me she had some smocks.”

“They should do.” She frowned. “All this because of Edith Perry. Why her?”

Ari picked up a damp cloth and ran it across a countertop. “I don’t know. A lot of people didn’t like her.”

“That’s the trouble. She sure spread it around equally, didn’t she? Ari?”

Ari turned. “What?”

“Have you thought that maybe you’re the real target?”

“What? Why?”

“Because of where she was killed. Maybe someone wants to frame you.”

“Oh, get real. No one hates me that much. Not even Ted.”

“Ted likes you too much.”

“He’s crazy, Di, but not like this.” Now she frowned. “Of course, I’ve wondered why it happened here.”

“You’ve got to admit there are a lot of weapons in a knitting shop.”

Ari stiffened. The cause of death was common knowledge. What wasn’t, was which yarn had been used, or exactly how. “Such as?”

Diane grinned, the unholy smile that Ari had learned long ago meant trouble. “The killer had to be pretty sharp.”

“What?”

“It’s the best place to needle someone.”

“That’s not funny, Di.”

Her grin broadened, in spite of, or maybe because of, Ari’s reaction. “Yeah, but you got the point.”

“Di—”

“I hope the police do, or they’ll get all tangled up.”

“You and I both are tangled up,” Ari snapped.

Diane had been looking around as if in search of another source of puns, but at that she looked at Ari. “What do you mean? I had nothing to do with it.”

“I’m afraid you did.” Ari took a deep breath. “She was strangled with your yarn.”

Product Details

- Publisher: Gallery Books (May 2, 2020)

- Length: 336 pages

- ISBN13: 9781982159993

Browse Related Books

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Died in the Wool Trade Paperback 9781982159993