Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

Table of Contents

About The Book

In the fall of 2003, as Iraq descended into civil war, Annia Ciezadlo spent her honeymoon in Baghdad. For the next six years, she lived in Baghdad and Beirut, where she dodged bullets during sectarian street battles, chronicled the Arab world’s first peaceful revolution, and watched Hezbollah commandos invade her Beirut neighborhood. Throughout all of it, she broke bread with Sunnis and Shiites, warlords and refugees, matriarchs and mullahs. Day of Honey is her story of the hunger for food and friendship during wartime—a communion that feeds the soul as much as the body.

In lush, fiercely intelligent prose, Ciezadlo uses food and the rituals of eating to uncover a vibrant Middle East most Americans never see. We get to know people like Roaa, a young Kurdish woman whose world shrinks under occupation to her own kitchen walls; Abu Rifaat, a Baghdad book lover who spends his days eavesdropping in the ancient city’s legendary cafés; and the unforgettable Umm Hassane, Ciezadlo’s sardonic Lebanese mother-in-law, who teaches her to cook rare family recipes (included in a mouthwatering appendix of Middle Eastern comfort food). From dinner in downtown Beirut to underground book clubs in Baghdad, Day of Honey is a profound exploration of everyday survival—a moving testament to the power of love and generosity to transcend the misery of war.

Excerpt

Introduction

The Siege

HE WAS ONE of an endangered species: among the few white, native-born cab drivers left in New York. Meaty, middle-aged, face like a potato. A Donegal tweed driving cap. He pulled up beside me, drew down the window, and growled out of the corner of his mouth: “You wanna ride?”

We rode in silence until we reached Atlantic Avenue. “You see this street?” he said, waving a massive hand at the windshield. “They’re all Arabs on this street.”

He was right, more or less. The conquest began in the late 1800s, as the Ottoman Empire waned and the Mediterranean silk trade collapsed. Between 1899 and 1932, a little over 100,000 “Syrians”—in those days, a catchall term for practically anyone from the Levant, the French name for the eastern Mediterranean—emigrated to the New World. Many of them settled in New York. In 1933, the Arab-American newspaper Syrian World described Atlantic Avenue, with gently sarcastic pride, as “the principal habitat of the species Syrianica.”

By 1998, the Atlantic Avenue strip was such a symbol of Arab-American identity that 20th Century Fox re-created it for a movie called The Siege. In the movie, Arab terrorists carry out a series of bombings in New York City, and the government imposes martial law and rounds up all the Arabs, guilty and innocent alike, into detention camps.

“These Arabs, yeah,” the cabbie continued. “They come over here, they try to act normal. Try to act like you and me. Like they’re fitting in, ya know?”

He barked out a laugh. “Turns out they’re al-Qaeda.”

It was a relief when people said it openly. I could talk to this guy. He was an ethnic American, and he assumed I was one too. He was right: I’m a Polish-Greek-Scotch-Irish mutt from working-class Chicago. A product of stockyards and steel mills and secretarial schools. I could see where he was coming from. I came from there myself.

But then again: the man I loved was named for Islam’s prophet. We had been seeing each other for about five months. I had thought of him as just another ethnic American, but now it was September 13, 2001, and suddenly nobody else seemed to see it that way. On September 11, the landlady had knocked on his door just before midnight. Mrs. Scanlon was an immigrant herself, from Ireland, and no doubt with terrorism-related memories of her own. In a high and quavering voice, she asked, “Mohamad, are you an Arab?”

I had been thinking about The Siege quite a bit since then.

When 20th Century Fox started filming The Siege in the late 1990s, I had just moved to the heavily Polish Brooklyn neighborhood of Greenpoint. Apparently the real Atlantic Avenue didn’t have enough brownstones to look like New York on film, so overnight, Hollywood set designers transformed Greenpoint’s Little Warsaw into a cinematic version of the Arab street. Awnings that had once read Obiady Polski (Polish Dinners) now surged with Arabic script. Tanks rolled past under klieg lights. Wandering down the imitation Atlantic Avenue, it was easy to imagine that all of our carefully constructed ethnic identities were nothing but Hollywood sets, as specious a notion as the species Syrianica, a scaffolding you could put up or tear down in a couple of hours.

The city had papered Greenpoint’s streetlights with flyers forbidding people to park because of Martial Law, the movie’s working title; as it happened, many Greenpointers had fled Poland in the early 1980s, when it was under actual Communist martial law. Middle-aged Polish émigrés would stop and glower at the Hollywood diktats with gloomy satisfaction: You see? I told you it would happen here too.

Back in September 2001, red and yellow traffic lights flowed over the dark windshield. The few cars ghosting down the empty avenue ignored them. Everyone ran red lights during the days after the attacks. Stopping seemed pointless, like everything else.

“No, man, that’s not true,” I said finally. “A lot of the Arabs here left their countries because they weren’t al-Qaeda. A lot of them left to get away from those guys.”

Al-Qaeda wouldn’t have had much use for my Arab: he’s a Shiite, at least by birth. But introducing the Sunni-Shiite divide seemed a little ambitious in this case. “They left cause their countries were messed up,” I said. “The ones that are here are the ones that wanted to come to America.”

He looked hard at me in the rearview mirror, his eyes flashing in the little strip of glass.

I sighed. “You know, most of the Arabs here in the U.S. are actually Christians.”

A cowardly argument. My own Arab was a Muslim, after all.

“Shyeah!” the cabbie spat. “They act like they’re Christians. They pretend. But they’re really al-Qaeda.”

Gray metal shutters hid the store windows, but memory filled in what I couldn’t see. Here on my right was Malko Karkanni’s shabby storefront, jammed with bins of olives and dusty coffeepots. Mr. Karkanni liked to talk; if you had time, he would pull out a stool, make you tea, and talk about the lack of human rights in Syria, the country he still missed. Ahead on the left was a restaurant named Fountain, with a real fountain inside, like an Ottoman courtyard; once, when I told the waiter where my grandmother was from, he broke into fluent Greek. And here was Sahadi’s, the famous deli and supermarket, run by a family that has been part of New York ever since 1895, when Abraham Sahadi opened his import-export company in lower Manhattan, back when my ancestors were still plowing fields in Scotland, Galicia, and the Peloponnese.

“Well, my boyfriend’s an Arab,” I said suddenly. The words tumbled out, high-pitched and breathless. “And he’s not al-Qaeda, and I have a lot of Arab friends, and they’re not al-Qaeda either!”

The eyes flashed back at me again, a little more anxiously this time. Was he going to kick me out of his car? Would he call the police, the FBI, and tell them about me and my Arab boyfriend?

Or would he just shake his head and decide that I was a fool—one of a breed of unfortunate women who marry foreign men, put them through flight school, and end up later on talk shows insisting that “he seemed so normal”? Like Annette Bening in The Siege, who falls for an educated Arab guy, a Palestinian college professor who acts normal but—you can’t trust them—turns out to be a terrorist in the end?

He thought about it for a block or two before he spoke. His voice was casual, and unexpectedly gentle, as if we had backed up and rewound the whole conversation to the beginning.

“You know that place Sahadi’s?” he said. “Y’ever been in there? They got some great food in there, yeah. Hummus, falafel, you know. Boy, that stuff is pretty good. You ever try it?”

There’s a saying in Arabic: Fi khibz wa meleh bainetna—there is bread and salt between us. It means that once we’ve eaten together, sharing bread and salt, the ancient symbols of hospitality, we cannot fight. It’s a lovely idea, that you can counter conflict with cuisine. And I don’t swallow it for a second. Just look at any civil war. Or at our own dinner tables, groaning with evidence to the contrary.

After September 11, liberal New Yorkers flocked to Arabic restaurants, Afghan, even Indian—anything that seemed vaguely Muslim, as if to say, “Hey, we know you’re not the bad guys. Look, we trust you, we’re eating your food.” New York newspapers ran stories about foreigners and their food, most of which followed much the same formula: the warmhearted émigré alludes mournfully to troubles in his homeland; assures the readers that not all Arabs/Afghans/Muslims are bad; and then shares his recipe for something involving eggplants. They were everywhere after September 11, photos of immigrants holding out plates of food, their eyes beseeching, “Don’t deport me! Have some hummus!” But a lot of them did get deported, and American soldiers got sent to Afghanistan and Iraq. A decade later, the lesson seems clear: You can eat eggplant until your toes turn purple, and it won’t stop governments from going to war.

But then again, there is something about food. Even the most ordinary dinner tells manifold stories of history, economics, and culture. You can experience a country and a people through its food in a way that you can’t through, say, its news broadcasts.

Food connects. In biblical times, people sealed contracts with salt, because it preserves, protects, and heals—an idea that goes back to the ancient Assyrians, who called a friend “a man of my salt.” Like Persephone’s pomegranate seeds, the alchemy of eating binds you to a place and a people. This bond is fragile; people who eat together one day can kill each other the next. All the more reason we should preserve it.

Many books narrate history as a series of wars: who won, who lost, who was to blame (usually the ones who lost). I look at history as a series of meals. War is part of our ongoing struggle to get food—most wars are over resources, after all, even when the parties pretend otherwise.

But food is also part of a deeper conflict, one that we all carry inside us: whether to stay in one place and settle down, or whether to stay on the move. The struggle between these two tendencies, whether it takes the form of war or not, shapes the story of human civilization. And so this is a book about war, but it is also about travel and migration, and how food helps people find or re-create their homes.

One of my old journalism professors, a man with the unforgettable name of Dick Blood, used to roar that if you want to write the story, you have to eat the meal. He was talking about Thanksgiving, when reporters visit homeless shelters, collect a few quotes, and head back to the newsroom to pump out heartwarming little features without ever tasting the turkey. But I’ve found that this command—“You have to eat the meal”—is a good rule for life in general. And so whenever I visit a new place, I pursue a private ritual: I never let myself leave without eating at least one local thing.

We all carry maps of the world in our heads. Mine, if you could see it, would resemble a gigantic dinner table, full of dishes from every place I’ve been. Spanish Harlem is a cubano. Tucson is avocado chicken. Chicago is yaprakis; Beirut is makdous; and Baghdad—well, Baghdad is another story.

In the fall of 2003, I spent my honeymoon in Baghdad. I’d married the boyfriend, who was also a reporter, and his newspaper had posted him to Iraq. So I moved to Beirut, with my brand-new husband and a few suitcases, and then to Baghdad.

For the next year, we tried to act like normal newlyweds. We did our laundry, went grocery shopping, and argued about what to have for dinner like any young couple, while reporting on the war. And throughout all of it, I cooked.

Some people construct work spaces when they travel, lining up their papers with care, stacking their books on the table, taping family pictures to the mirror. When I’m in a strange new city and feeling rootless, I cook. No matter how inhospitable the room or the streets outside, I construct a little field kitchen. In Baghdad, it was a hot plate plugged into a dubious electrical socket in the hallway outside the bathroom. I haunt the local markets and cook whatever I find: fresh green almonds, fleshy black figs, just-killed chickens with their heads still on. I cook to comprehend the place I’ve landed in, to touch and feel and take in the raw materials of my new surroundings. I cook foods that seem familiar and foods that seem strange. I cook because eating has always been my most reliable way of understanding the world. I cook because I am always, always hungry. And I cook for that oldest of reasons: to banish loneliness, homesickness, the persistent feeling that I don’t belong in a place. If you can conjure something of substance from the flux of your life—if you can anchor yourself in the earth, like Antaeus, the mythical giant who grew stronger every time his feet touched the ground—you are at home in the world, at least for that meal.

In every war zone, there is another battle, a shadow conflict that rages quietly behind the scenes. You don’t see much of it on television or in the movies. This hidden war consists of the slow but relentless destruction of everyday civilian life: The children can’t go to school. The pregnant woman can’t give birth at a hospital. The farmer can’t plow his fields. The musician can’t play his guitar. The professor can’t teach her class. For civilians, war becomes a relentless accumulation of can’ts.

But no matter what else you can’t do, you still have to eat. During wartime, people’s lives begin to revolve around food: first to stay alive, but also to stay human. Food restores a sense of familiarity. It allows us to reach out to others, because cooking and eating are often communal activities. Food can cut across social barriers, spanning class and sectarian lines (though it can also, of course, reinforce them). Making and sharing food are essential to maintaining the rhythms of everyday life.

I went to the Middle East like most Americans, relatively naive about both Arab culture and American foreign policy. Over the next six years, I saw plenty of war, but I also saw normal, everyday life. I sat through ceremonial dinners with tribal sheikhs in Baghdad; kneeled and ate kubbet hamudh on the floor with Iraqi women from Fallujah; drank home-brewed arak with Christian militiamen in the mountains of Lebanon; feasted on boiled turkey with a mild-mannered peshmerga warlord in Kurdistan; and learned how to make yakhnet kusa and many other dishes from my Lebanese mother-in-law, Umm Hassane, who doesn’t speak a word of English. Other people saw more, did more, risked more. But I ate more.

If you want to understand war, you have to understand everyday life first. The dominant narrative of the Middle East is perpetual conflict: the bombs and the bullets and the battles are always different, and yet always, somehow, depressingly the same. And so this book is not about the ever-evolving ways in which people kill or die during wars but about how they live before, during, and after those wars. It’s about the millions of small ways people cope—the ways they arrange their lives, under sometimes unimaginable stress and hardship, and the ways they survive.

Every society has an immune system, a silent army that tries to bring the body politic back to homeostasis. People find ways to reconstruct their daily lives from the shambles of war; like my friend Leena, who once held a dinner party in her Beirut bomb shelter, they work with what they have. This is the story of that other war, the one that takes place in the moments between bombings: the baker keeps the communal oven going so his neighborhood can have bread; the restaurateur converts his café into a refugee center; the farmer feeds his neighbors from his dwindling stock of preserves; the parents drive all over Baghdad trying to find an open bakery so their daughter can have a birthday cake. They are warriors just as much as those who carry guns. There are many ways to save civilization. One of the simplest is with food.

Reading Group Guide

Get a FREE ebook by joining our mailing list today! Plus, receive recommendations for your next Book Club read.

INTRODUCTION

In the fall of 2003, Annia Ciezadlo spent her honeymoon in Baghdad. Determined to make a life and a career in the Middle East with her new Lebanese husband, Annia spent the next six years in Beirut and Baghdad, cooking and eating with Shiites and Sunnis, refugees and warlords, matriarchs and mullahs. It is from these meals that Annia discovers what she calls a “shadow war”—a hidden conflict that slowly destroys lives, divides families, and poisons daily life. In war zones, the precious ordinariness of cooking takes on new meaning. From hurried meals accompanied by gunfire to lavish family feasts, Annia discovers that civilians use food to feed the soul as much as the body in times of war.

QUESTIONS AND TOPICS FOR DISCUSSION

- Day of Honey opens with an introduction, titled “The Siege,” that takes place soon after 9/11 in New York City. Why do you think Annia begins her memoir here, with a taxi ride down Brooklyn’s Atlantic Avenue? How does this introduction set the scene for the rest of the book?

- One important theme of Day of Honey is the question of home. Do you agree with Annia that “home could be something you made instead of the place where you lived” (p. 24)? Is home a fixed location, or is it a movable feast?

- Discuss the relationship between Annia’s nomadic teenage years and her personal connection to food. Do you think Annia’s travels through America influenced her experience in the Middle East?

- “How do you like Beirut?” (p. 34). It’s the question everyone asks Annia during her first visit to her future home. What are Annia’s first impressions of Beirut? Which of the city’s pleasures does she discover right away, and which does she find later, as a resident?

- Annia identifies what she refers to as a “shadow conflict” in times of war that she defines as “the slow but relentless destruction of everyday civilian life” (p. 8). Of all the everyday freedoms that are lost in Baghdad and Beirut, which loss seems the most tragic? Which of Annia’s new friends and acquaintances fall victim to this “shadow war,” and which manage to adapt during times of conflict?

- Compare Annia’s childhood to Mohamad’s. How were their early environments different, and how were they similar? What challenges did each of them face growing up? What factors made each of them a “reluctant nomad (p. 25)”?

- On page 265, Annia writes: “You are reading my account of one war—my imperfect memories of what I saw and felt and did. Others had their own perceptions and their own realities.” What does she mean by this? Is she writing as a journalist, or a human being, or both?

- When Annia arrives in Baghdad, she finds that most outsiders describe Iraqi food as “the real weapon of mass destruction” (p. 66). Why does Annia take this as a personal challenge, and how does she prove them wrong? Why have outsiders misjudged Iraqi cuisine?

- Discuss the theme of hospitality in Day of Honey. How does Annia react to this Middle Eastern tradition? Annia learns early on to “never, ever turn down a meal” (p. 113). What kinds of homes, meals, and dangers does Annia encounter as a result?

- Consider the story of Roaa, Annia’s translator who grew up in war-torn Iraq. How does Roaa feel about her country’s history and its prospects for the future? Do you think Roaa and her husband, now living in Colorado, will ever be able to “make” themselves settle down, as Roaa puts it (p. 318)? Why or why not?

- According to Annia, “My idea of paradise is more like Mutanabbi Street, in Baghdad’s old city: an entire city street with no cars, just books and cafés” (p. 105). How does Mutanabbi Street demonstrate Iraqis’ love for the written word? What solace does Annia find on Mutanabbi Street, and why must she eventually stop going there? Have you ever encountered a city, street, or place that felt like your idea of paradise?

- Annia was living in Baghdad when Saddam Hussein was finally captured. How do Annia’s Iraqi friends respond to this historical event? Annia writes, “The flavor of freedom was more complex, more bitter than we imagined” (p. 120). Did Annia’s account of the United State’s occupation of Iraq change your perspective or understanding of current events?

- Discuss the unique challenges that women—the “face of Iraq”—must contend with (p. 140). Why is Dr. Salama, a popular female politician, a complicated spokeswoman for women’s rights in Iraq? What does Annia learn about Iraqi women and politics from her conversations with Dr. Salama? How did you react to these events in the book?

- Consider the strong personality of Umm Hassane, Annia’s mother-in-law. What are Annia’s first impressions of Umm Hassane, and how does Annia’s opinion of her mother-in-law evolve over the course of the book? What can we learn about Umm Hassane’s character from her cooking style? How does Annia find “the real story” of the war by cooking with Umm Hassane (p. 275)? Does Umm Hassane remind you of anyone you know?

- Discuss the early years of Annia and Mohamad’s marriage. What are the main sources of tension in their relationship? Were you able to relate to their everyday squabbles? Why or why not? Why do you think she includes these incidents in her accounts of historic events?

- Why does Annia return to Beirut in the fall of 2007, after Mohamad finds a job in New York? What do you think Mohamad means when he says, “the war would never end...you ended it yourself” (p. 313)? How does Annia manage to end her dangerous attachment to Beirut?

ENHANCE YOUR BOOK CLUB

- Move your book club to the kitchen and try out one of Annia’s delicious recipes! Decide in advance which dish to try, and ask each member of your book club to bring ingredients. When it’s time to eat, wish everyone “Sahtain!”

- Annia imagines an “edible map” of Beirut, with all her favorite shops and restaurants marked (p. 178). Make an “edible map” of where you live by marking your top food spots on a map of your town. Compare your edible map with other member’s maps from your book club.

- Annia states that every city has its own question—Beirut’s is “How do you like Beirut?” while New York City’s is “What do you do?” Discuss this idea with your group and decide on a question that embodies your own city or countryside.

- Donate to a charity that helps citizens in Iraq. For a list of effective organizations working in Iraq, visit the website of the American Institute of Philanthropy: http://www.charitywatch.org/hottopics/iraqaid.html. You can also volunteer to help Iraqi refugees in America by contacting the International Rescue Committee.

- To read more by Annia Ciezadlo, including many of the articles she wrote in Baghdad and Beirut, visit her website at http://www.anniaciezadlo.com.

A CONVERSATION WITH ANNIA CIEZADLO

Please tell us how you chose the title for your book. What does the Arabic proverb “day of honey, day of onions” mean to you? Where did you first learn or hear of this saying?

It’s from an old Arabic saying that goes youm aasl, youm basl—day of honey, day of onions. I don’t remember exactly where I first heard it, but I’ve seen people use it in a multitude of ways: sometimes to comfort each other, at other times ironically. It’s hopeful and cynical at the same time. One day might be sweet, the next bitter, but you keep going. You taste the honey while you can. For me, it sums up a wise, beleaguered optimism that the Palestinian writer Emile Habiby called pessoptimism: that no matter how bad things get, you don’t lose your faith in human nature. Or your deep conviction that something disastrous is just about to happen.

When did you start writing Day of Honey? How did you decide to focus your book on the struggles of everyday life in Beirut and Baghdad?

It was July of 2005. I was standing at the sink—the tiny little sink I wrote about in the book—washing dishes and thinking about how different Lebanon was from how I’d pictured it. Our tiny kitchen was stuffed with zaatar and wild arugula that I’d bought from Umm Adnan, the woman who sold wild greens on the sidewalk in our neighborhood, and gorgeous little intense tomatoes, and it suddenly struck me: What if Americans could see this side of life in Lebanon, not to mention the entire Middle East? The side of Lebanon that’s ridiculously generous, down-to-earth, and lush—the side we so rarely see depicted, because we’re focusing on militants and conflict. I had been writing mostly political analysis out of Lebanon, Iraq, and Syria, because that’s what most editors wanted. But readers are always interested in the little details that make up the fabric of everyday life: What do people look like? What do they eat? What do they talk about over the dinner table? What are their hopes, fears, and dreams? I realized that if I wrote about these things it would translate the abstraction of Middle Eastern politics into something that people would be able to relate to. So the idea for the book literally came from the kitchen sink.

When did you first realize that you had a personal story to tell?

I kept a diary the whole time I was in the Middle East (some days more faithfully than others). But I was always more interested in other people’s stories than my own—which is probably why I became a journalist. With Day of Honey, I realized that I had to tell my own story in order to write about the people whose lives I shared in Beirut and Baghdad. As an American woman married to a Lebanese man, I had access to a world of families and domestic life that most foreigners never get to see. Food was a window into that world: the dinner table was where I would learn new words, hear new opinions, where people would open up. Writing about meals was a way of letting readers get a glimpse of this unseen world, which I had the unique privilege of being able to see as both an insider and an outsider at the same time. Telling my own story was a way to introduce other people’s stories and points of view in a way that was more natural, and more honest, than pretending to be a fly on the wall.

Although most of your memoir takes place in the Middle East, many of the problems you face will sound familiar to American readers, from apartment hunts to in-laws. How much of Day of Honey do you think your readers will be able to relate to?

A lot, I think. America is going through a wave of foreclosures right now that is unlike anything we’ve seen since the Great Depression. There’s a big difference between losing your home in a war and losing it in a financial collapse, but there are some similarities too. You have to move, perhaps to a strange city, and re-adjust. You or your children have to start new schools, make new friends, and go through the homesickness of that lonely adjustment period. So I think that aspect of the book is something a lot of Americans will be able to relate to right now. During my teenaged years, when I was moving around a lot, I would go to the public library and stock up on books about the American civil war, or ancient Greece, or World War II, or even novels like The Lord of the Rings trilogy. Reading about people living through times of upheaval made me feel less alone—less singled out by hard times or disaster, and more in awe of people who had much bigger problems than mine. So if readers have a similar reaction to Day of Honey, that would make me very happy.

Day of Honey includes so many voices in addition to your own. Which of your relatives and friends in the Middle East will be getting a copy of the book? Has anybody objected to the way you portrayed him or her?

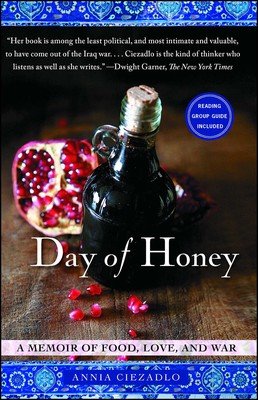

Everyone will get a copy, but not all of them can read it. Umm Hassane doesn’t speak any English, so we’ll have to translate or paraphrase it for her. But I think she’ll like seeing the beautiful cover photo (which was taken by my friend Barbara Massaad, the fabulous Lebanese cookbook writer). After the manuscript was finished, but before it came out, I showed it to some of my friends from Beirut and Baghdad. They loved it, but it was hard for them to read. It brought back memories of wars they had lived through. A couple of them called me in tears while they were reading it. It was a good reminder for me that words have a great deal of power, and you have to be mindful of their impact on other people.

Besides the rich data of your personal experience, what kind of research did you conduct before writing Day of Honey?

Way too much! This is probably thanks to my background as a journalist, where it’s normal do about ten times more research and reporting than what you actually end up putting in your article. If I’ve learned anything from living through these historic events in the Middle East, it’s that you have to know the history in order to understand the latest headlines coming out of the Middle East. That’s part of the reason I put so much history in Day of Honey. So in addition to the hundreds of people I interviewed in my years in the Middle East, I also spent three years researching food and Middle Eastern history. I read books about the topography of medieval Baghdad, classical Arabic food poetry, and ancient Mesopotamian beer. I went on a history bender. I read a history of salt (by the magnificently obsessive Mark Kurlansky) and a history of sugar (Sidney Mintz’s brilliant Sweetness and Power). A lot of these books are included in the bibliography; if you want to geek out on Middle Eastern food and history, it’s a good place to start.

What surprised you most about Beirut and Baghdad? How did your view of the Middle East change after living there for over six years?

We get most of our images of the Middle East from wars. A bomb goes off, the television crews go film it, and we see people jumping up and down and shouting and waving their fists. No wonder we think they hate us. But most of the ordinary people I met, with a few exceptions, didn’t hate Americans. Quite the reverse—they would often ask me, with genuine puzzlement, why we hated them. It was such a perfect reversal of the stereotype that sometimes I almost had to laugh. Many people in the Middle East are deeply angry about U.S. foreign policy. But almost everyone I met in Baghdad, Damascus, or Beirut—with a few notable exceptions—made the crucial distinction between our country’s government and its people. That’s a distinction we don’t always make with them. But I think we should. And that’s why I focused on the ordinary people whose voices are often drowned out by militants or demagogues.

Did you have culture shock on moving to the Middle East?

Baghdad was a fascinating place because it was frozen in time—under Saddam Hussein, it was cut off from the rest of the world for decades. After the American invasion, it was opened up to the rest of the world, and in a sense everyone in Iraq had culture shock. Beirut is different. It’s wordly, sophisticated, and yet traditional at the same time. In Beirut, my friends would always warn me not to be taken in by the city’s cosmopolitanism. For example, I would often be surprised to hear young people with college degrees, who were intelligent and well-traveled, and otherwise liberal, speak against interfaith marriage. And I heard this from both Christians and Muslims.

One of the hardest things was reminding myself that even though people might look familiar, sound familiar, and eat grape leaves that taste like my grandmother’s, they had completely different histories and associations than mine. People all over the world want the same things: to grow up, get an education, get married and have kids and give them a good life. But they want them in different ways. I might not agree with a Muslim woman who wants Islamic law, or a Christian man who’s opposed to interfaith marriage. But I think it’s important to understand why they might want these things, and that it doesn’t necessarily make them bad people.

What was it like being an American woman in the Middle East?

People ask me that a lot. I’d like to say that I struggled terribly, but the truth is that, for a reporter, being female was actually a tremendous competitive advantage. People find you less threatening. They’re quicker to let their guard down and reveal what they really think. They’re more likely to invite you into their homes and introduce you to their families. Being female gives you incredible access to that unseen world of private life that most Americans never glimpse. When was the last time you read a substantial article about Iraqi women’s political rights? Or a long magazine profile about someone like Dr. Salama al-Khafaji—and trust me, the Middle East is full of women as remarkable as her? I see them as the real story, and I think a lot of Americans want to read that untold story. Which is why I wrote this book.

It’s clear in the memoir that your Greek- and Polish-American heritage influenced both your point of view and your palate. Have you considered writing more about the experiences and recipes of your life before the Middle East?

Yes, absolutely. I never started out thinking “I want to go cover wars in the Middle East.” I began my career as a journalist writing for a tiny community-based newspaper in upstate New York. We covered everything from housing scandals and local government to parking tickets. I went to journalism school because I wanted to keep doing that kind of reporting—about city politics, and small-time corruption, and the daily struggles of ordinary people against the forces of bureaucracy and greed. These are stories you can find anywhere, all over the world, including here in the USA. I could write a whole book just about my grandparents, never mind the extraordinary people I’ve met over the years. I’ll keep writing these kinds of stories as long as people want to read them.

How do you describe your varied writing career—do you identify yourself as a memoirist, a journalist, a food writer, a war correspondent, or something else?

All of the above.

In the mouth-watering recipes you provide at the end of your book, you encourage the reader, “Invent your own (p. 337).” How much have you strayed from tradition in these Middle Eastern recipes? What do you find rewarding about inventing your own versions?

I like to improvise. When I’m cooking for myself, I’ll try anything. But I’ve changed the recipes in Day of Honey only very slightly from the originals—enough to make them a little more familiar, and to suggest variations. For example, Umm Hassane doesn’t put carrot and celery in her chicken stock, only onions. And people in Lebanon, with some exceptions, don’t use nearly as much spice or hot pepper as we’re accustomed to in the United States. But I kept alterations to a minimum—far, far less than I would normally do at home—because I wanted readers to taste the flavors that I write about in the book.

But while these are mostly Umm Hassane’s traditional recipes, I think it’s important to note that no tradition is set in stone. There is no one “Lebanese” version of mjadara: Umm Hassane’s mjadara is different from Aunt Khadija’s, which is different from Batoul’s, and that’s just the variation within one family. People from two different parts of Lebanon will disagree passionately over the true, correct, and “traditional” way to make kibbeh nayeh—and each may say the other is wrong, but in fact they’re both correct. I was sitting at a table once with some friends in Beirut, and I asked them what their definition of mjadara was. There were five of us at the table, and each one of us had a completely different version. It was a perfect illustration of the old saying about four Lebanese having five opinions—equally true with politics or food.

You chronicle all sorts of flavors in Day of Honey, from delectable meze to celebratory pudding. Of the recipes you provide to readers, which do you make most often?

Fattoush. I make it all the time. I change it according to what’s in season, what’s in my pantry, and how I feel that day. In the spring I might throw in shaved fennel or red bell peppers. In the winter I make it with pomegranate seeds instead of tomatoes. Or maybe avocado. Just don’t tell Umm Hassane!

Product Details

- Publisher: Free Press (February 14, 2012)

- Length: 416 pages

- ISBN13: 9781416583943

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

”Ciezadlo's lovely, natural language succeeds where news reports often fail: She leads us to care.”

—The Oregonian

“Her book is full of more insight and joy than anything else I have read on Iraq. . . . Ciezadlo is a wonderful traveling companion. Her observations are delightful — witty, intelligent and nonjudgmental.”

—The Washington Post Book World

“Her writing about food is both evocative and loving; this is a woman who clearly enjoys a meal... A glass of Iraqi tea, under Ciezadlo's gaze, is a thing of beauty.”

—The Associated Press

“In her extraordinary debut, Annia Ciezadlo turns food into a language, a set of signs and connections, that helps tie together a complex moving memoir of the Middle East."

—The Globe and Mail

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Day of Honey Trade Paperback 9781416583943

- Author Photo (jpg): Annia Ciezadlo Photo by Mohamad Bazzi(3.0 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit