Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

LIST PRICE $17.99

PRICE MAY VARY BY RETAILER

Digital products purchased on SimonandSchuster.com must be read on the Simon & Schuster Books app. Learn more.

Get 30% off hardcovers with code MOM30, plus free shipping on orders of $40 or more. Terms apply.

Buy from Other Retailers

Table of Contents

About The Book

In remembrance of the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz and the Nazi concentration camps, this award-winning, bestselling work of Holocaust fiction, inspiration for the classic film and “masterful account of the growth of the human soul” (Los Angeles Times Book Review), returns with an all-new introduction by the author.

An “extraordinary” (The New York Review of Books) novel based on the true story of how German war profiteer and factory director Oskar Schindler came to save more Jews from the gas chambers than any other single person during World War II. In this milestone of Holocaust literature, Thomas Keneally, author of The Book of Science and Antiquities and The Daughter of Mars, uses the actual testimony of the Schindlerjuden—Schindler’s Jews—to brilliantly portray the courage and cunning of a good man in the midst of unspeakable evil. “Astounding…in this case the truth is far more powerful than anything the imagination could invent” (Newsweek).

An “extraordinary” (The New York Review of Books) novel based on the true story of how German war profiteer and factory director Oskar Schindler came to save more Jews from the gas chambers than any other single person during World War II. In this milestone of Holocaust literature, Thomas Keneally, author of The Book of Science and Antiquities and The Daughter of Mars, uses the actual testimony of the Schindlerjuden—Schindler’s Jews—to brilliantly portray the courage and cunning of a good man in the midst of unspeakable evil. “Astounding…in this case the truth is far more powerful than anything the imagination could invent” (Newsweek).

Reading Group Guide

Get a FREE audiobook by joining our mailing list today! Plus, receive recommendations for your next Book Club read.

By clicking 'Sign me up' I agree to the Terms of Use and acknowledge the Privacy Policy and Notice of Financial Incentive. Free audiobook offer available to NEW US subscribers only. Offer redeemable at Simon & Schuster's audiobook fulfillment partner. Must redeem within 90 days. See full terms and conditions and this month's choices.

Reading Group Discussion Points

- Schindler's List, while based on the true story of Oskar Schindler and the Schindler Jews, is fiction. At what point does this novel depart from the merely factual? What "liberties" does Thomas Keneally take that a non-fiction author could not?

- At the start of the book, Keneally lets us know that his protagonist, Oskar Schindler, is not a virtuous man, but rather a flawed, conflicted one, who makes no apology for his penchant for women and drink; yet he gambles millions to save the Jews under his care from the gas chambers. How does Keneally reconcile these two distinctly different sides of Oskar Schindler? How do you, the reader, reconcile them?

- Keneally writes, "And although Herr Schindler's merit is well documented, it is a feature of his ambiguity that he worked within or, at least, on the strength of a corrupt and savage scheme, one that filled Europe with camps of varying but consistent inhumanity." What abiding differences were there between Oskar Schindler and men like Amon Goeth, who operated the controls of this system? To what extent did Schindler remain in partnership with them? Where did he draw the line, and how did he keep himself separate while living among them?

- Schindler and his mistress, Ingrid, ride their horses to the hill overlooking the Cracow ghetto, where they witness an Aktion. Trailing alone at the end of a line of people being marched off, Oskar and Ingrid spot a little girl in red, "the scarlet girl." What is it about her presence on this early morning that is instrumental in Oskar Schindler's sudden and terrible understanding of what is happening in Europe and of his responsibility to mitigate it?

- "I am now resolved to do everything in my power to defeat the system," Schindler says after witnessing this Aktion. Do Schindler's subsequent actions defeat the system, or does he merely help to perpetuate it?

- Keneally follows many other characters throughout the book: the prisoners, Itzhak Stern, Helen Hirsch, Poldek and Mila Pfefferberg, Josef and Rebecca, the Rosner brothers -- all of whom, at points, rise above their circumstances and engage in acts of great courage and generosity. In contrast, characters such as Spira and Chilowicz engage in acts of cruelty and self-interest. Yet they have similar circumstances. How do you feel about these different characters and their choices?

- "All our vision of deliverance is futile. We'll have to wait a little longer for our freedom," Schindler says to Garde (a Brinnlitz prisoner) when they learn that the Führer is still alive after an attempt on his life. Oskar speaks as if they are both prisoners waiting to be liberated, as if they have equivalent needs. What do you think Schindler means by "our freedom"? How might Schindler and other Germans have felt to be imprisoned? Is it fair for him to equate himself with Garde?

- After Brinnlitz is liberated, some of the prisoners take a German Kapo and hang him from a beam. Keneally writes, "It was an event, this first homicide of peace, which many Brinnlitz people would forever abhor. They had seen Amon hang poor engineer Krautwirt on the Appellplatz at Plaszow, and this hanging, though for different reasons, sickened them as profoundly." Why are so many of the prisoners sickened, in light of the atrocities committed against them? Do you feel the prisoners would have been justified in killing as many Germans as they could have? Why do you think there aren't more rampant acts of vengeance on the part of Schindler's Jews after their liberation?

- In a documentary made in 1973 by German television, Emilie Schindler remarked that Oskar had "done nothing astounding before the war and had been unexceptional since." She suggested that it was fortunate that between 1939 and 1945 he had met people who had summoned forth his "deeper talents." What are these "deeper talents" and what is it about war that elicits them? And what is it about peacetime that suppresses them?

- After the war, Schindler never reached the level of success he'd known during wartime. Both of his enterprises, a farm in Argentina and a cement factory in Frankfurt failed, and he was to fall back on Schindler's Jews time and time again. They became his only emotional and financial security, and they would help him in many ways until the day he died. Keneally suggests that Schindler remained, in a most thorough sense, a hostage to Brinnlitz and Emalia. What might he mean by this? Do you agree?

- What vision of human nature does Schindler's List express? Does it express the view of human beings as fundamentally good or evil? As immutable or capable of transformation? Does it leave you with any kind of a message, any vision for mankind? If so, what is it?

- Diary of a Young Girl, Anne Frank

Doubleday, 1967 - Dita Saxova, Arnost Lustig

Northwestern University Press, 1979 - The Holocaust in History, Michael Marrus

NAL/Dutton, 1989 - The Jews: Stories of a People, Howard M. Fast

Dell, 1968 - Maus I and Maus II, Art Spiegelman

Pantheon, 1991 - Night, Dawn, and Day, Elie Wiesel

Jason Aronson, Inc., 1985 - One, By One, By One, Judith Miller

Touchstone Books, 1990 - Sophie's Choice, William Styron

Vintage Books, 1979 - Stones from the River, Ursula Hegi

Scribner Paperback Fiction, 1995 - The War Against the Jews: 1933-1945, Lucy Dawidowicz

- Bantam Books, 1986

- Winter in the Morning, Janina Bauman

The Free Press, 1986

About The Reader

Product Details

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster Audio (December 1, 1993)

- Runtime: 4 hours

- ISBN13: 9780743548045

Browse Related Books

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

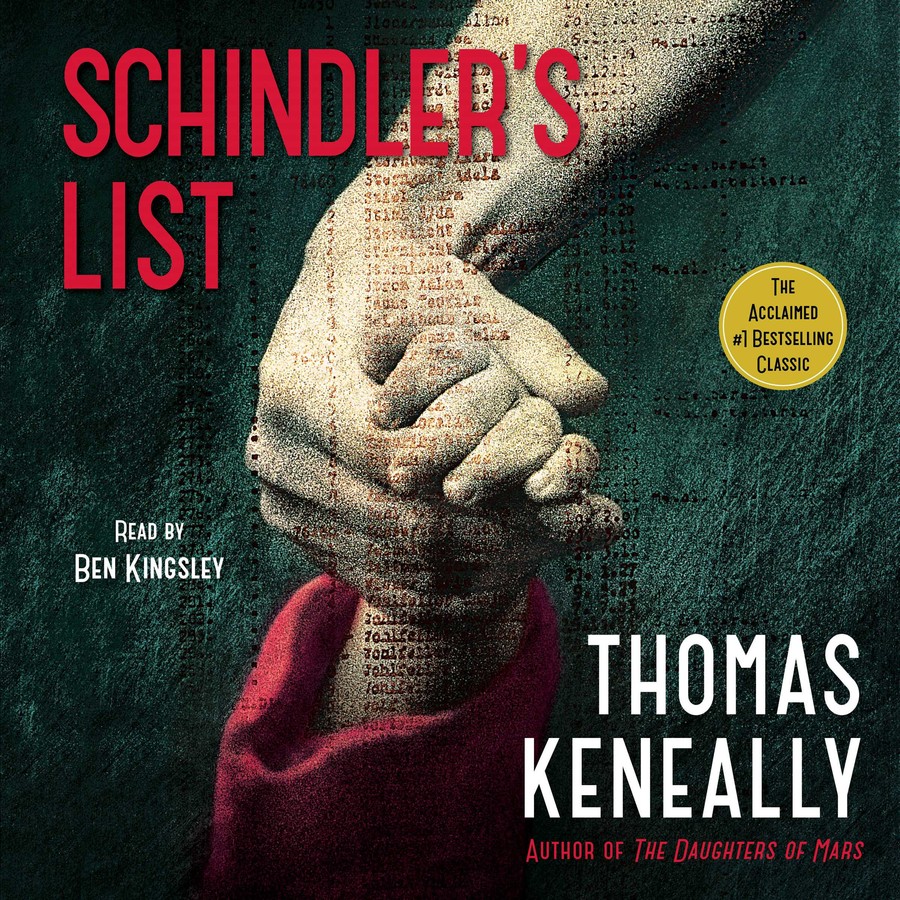

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Schindler's List Abridged Audio Download 9780743548045

- Author Photo (jpg): Thomas Keneally Photograph © Newspix via Getty Images(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit