Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

Millennial Nuns

Reflections on Living a Spiritual Life in a World of Social Media

Table of Contents

About The Book

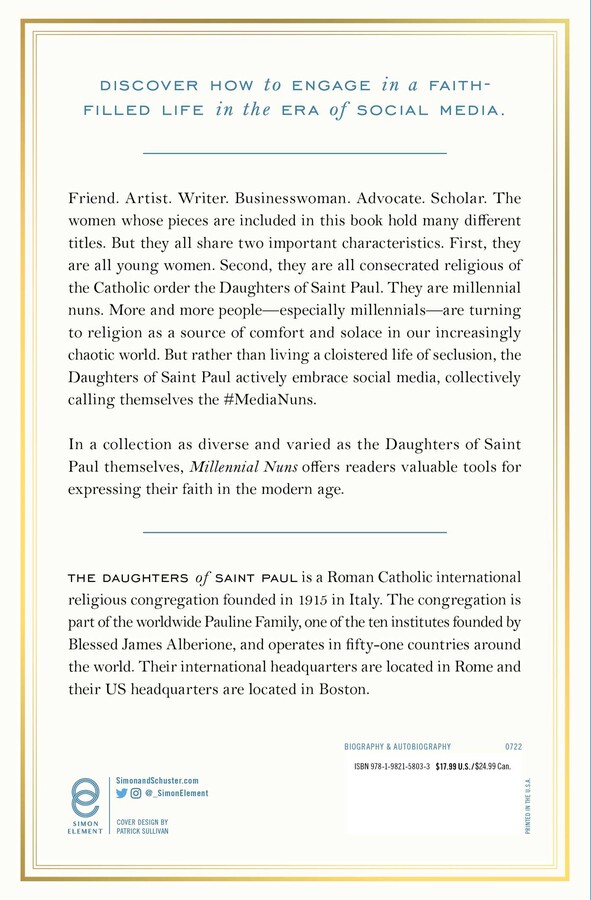

Discover how to engage in a faith-filled life in the era of social media from a group of young, consecrated Catholic sisters.

Friend. Artist. Writer. Businesswomen. Advocate. Scholar. The women whose pieces are included in this book hold many different titles. But they all share two important characteristics. First, they are all young women. Second, they are all consecrated religious of the Catholic order the Daughters of Saint Paul. They are millennial nuns.

More and more people—especially millennials—are turning to religion as a source of comfort and solace in our increasingly chaotic world. But rather than live a cloistered life of seclusion, the Daughters of Saint Paul actively embrace social media, using platforms like Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook to evangelize, collectively calling themselves the #MediaNuns.

In this “funny and poignant” (Colleen Carroll Campbell, award-winning author of The Heart of Perfection) memoir, eight of these Sisters share their own discernment journeys, struggles, and crises of faith that they’ve overcome, and episodes from their daily lives. Through these reflections, the Sisters also offer practical takeaways and tips for living a more spiritually-fulfilled life, no matter your religious affiliation.

In a collection as diverse and varied as the Daughters of Saint Paul themselves, Millennial Nuns will appeal to anyone looking to discover more about balancing faith with the modern age.

Friend. Artist. Writer. Businesswomen. Advocate. Scholar. The women whose pieces are included in this book hold many different titles. But they all share two important characteristics. First, they are all young women. Second, they are all consecrated religious of the Catholic order the Daughters of Saint Paul. They are millennial nuns.

More and more people—especially millennials—are turning to religion as a source of comfort and solace in our increasingly chaotic world. But rather than live a cloistered life of seclusion, the Daughters of Saint Paul actively embrace social media, using platforms like Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook to evangelize, collectively calling themselves the #MediaNuns.

In this “funny and poignant” (Colleen Carroll Campbell, award-winning author of The Heart of Perfection) memoir, eight of these Sisters share their own discernment journeys, struggles, and crises of faith that they’ve overcome, and episodes from their daily lives. Through these reflections, the Sisters also offer practical takeaways and tips for living a more spiritually-fulfilled life, no matter your religious affiliation.

In a collection as diverse and varied as the Daughters of Saint Paul themselves, Millennial Nuns will appeal to anyone looking to discover more about balancing faith with the modern age.

Excerpt

1. Learning the Language: Meeting God through the Vows of Religious Life LEARNING THE LANGUAGE MEETING GOD through the VOWS of RELIGIOUS LIFE SR. AMANDA MARIE DETRY, FSP

I had just unscrewed the gas cap of our Pontiac Montana when the hot August wind lunged after my veil and whipped it across my face. Again. I was in my second month of vowed religious life and still adjusting to many things, including my new relationship with nature. I gently brushed my veil as far away from the gas pump as possible and began to fill our tank.

Minutes later, a car pulled up at the neighboring pump. A middle-age man stepped out, saw me fighting to keep my veil from wrapping around the fuel hose, and walked in my direction. My stomach danced. Veil or no veil, I am an introvert; and now, thanks to the infinite creativity of God, I had become an introvert who stood out in a crowd.

“Hey! I have a question for you,” the man asked. He took a few steps closer. “What made you want to do that?”

I knew he wasn’t asking about the gas fill-up.

I paused for a moment as a million answers welled up in my mind and in my heart. Lord, what do I say? Where do I begin? Suddenly every answer vanished—except one. The right one. The only one. I looked him in the eyes and gave a shy smile: “Because I’m in love.”

My parents named me “Amanda,” which is Latin for “she who must be loved.” It is a name that is much easier to carry around with me than it is to live out. In fact, the first time I heard what it means, I resisted the definition. It sounded arrogant to my adolescent ears. I must be loved? Really?

The verb “love” has a necessity and an urgency about it. God actually commands it: “You shall love the Lord your God.” When I heard these words as a young Catholic, I wondered if love could really be commanded. I further wondered how I should respond to this command when I didn’t feel any special affection toward God. He was a distant, bearded figure who asked us to do things and never seemed to offer any feedback—at least not in the way my parents and teachers did. Even if I could conjure up some feelings of love for Him, when would I feel Him love me back?

Some years ago, an astute five-year-old reminded me that love was never meant to be analyzed or dissected like this. Children don’t ponder the “command” of love, how necessary love is, or how best to do it. They simply love. I watched this happen during a mission trip to Texas, as my sisters and I spent an evening at the home of good friends of our community. Their young daughter wanted to show me something in the backyard. I followed her outside, and after taking a hard look at whatever she was pointing at, we both were suddenly distracted by the immense ink-black, diamond-studded Texas sky that stretched over our heads. As we cranked our heads back in wonder, the little girl spontaneously uttered three small words: “I love God!” Then she stooped to the ground and started digging a hole in her mother’s flower beds. “I love God, too,” I whispered after her, but it sounded pathetic rolling off my lips. She had the spontaneity and the heart; I was stumbling after her, trying to keep up.

Children seem to have a natural capacity to speak to God and raise their hearts to Him. How do we all seem to lose this as we grow up? Or perhaps more importantly, how do we get it back?

My life as a religious sister is about learning this language of God—a language not of words, but of life. God’s word to us is not a jumble of letters and sounds, but a person: Jesus Christ. As Daughters of Saint Paul, we live our lives in relationship with this Word. We encounter Jesus speaking to us in Scripture, in the Church, and in our everyday experience of being human, and we continually bring our lives into conformity with His so that we, too, might speak of God. Of course, none of us speak this divine language perfectly. The “accent” of our failures and limitations betrays our lack of fluency. But God is generous and eager to teach. His desire to call forth the image of His Son in each one of us is a bit like Gandalf’s approach to Bilbo in The Hobbit, when Gandalf knocks on Bilbo’s door with a startling invitation: “I am looking for someone to share in an adventure that I am arranging, and it’s very difficult to find anyone.” God is always knocking at our door. We’re just not always home to hear it.

Over the years, I have learned to recognize God’s “knocks” as ardent but subtle, filled with respect for my free will and love for my humanity. God has knocked on my pursuit of success and achievement, my relationships with others, and the situations that had me most convinced that He was absent. And with each knock, He has invited me to step beyond the constricted Hobbit hole of human understanding and convenience and learn to speak the language of His love—which is nothing less than the poor, chaste, and obedient life of Christ.

I professed the religious vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience for the first time in June of 2019. In doing so, I said yes to the adventure of following Christ more closely and immersing myself in the language of God’s love. Jesus has been my Way, Truth, and Life on every twist and turn of this journey, and every day He offers me another glimpse of what it means to love and to be “in love”—which is to say, to be “in Him.”

The Language of Poverty

The books made an unceremonious thud as they hit the library table. My backpack was next, followed by a laptop and a thermos full of coffee. These would be my companions for the next several hours. My mind was already churning as I pulled up a chair and began to brainstorm several possible directions for my history paper. Minutes later, my fingers began their rhythmic scramble across my keyboard, punching out the results of my research on the political and gendered leanings of sixteenth-century British periodicals. After an hour of writing, my brain began to drift more pensively over the task at hand; then it stopped entirely.

What was I doing?

It was my junior year of college and my postgraduate dreams were supposedly at their peak. I had spent the prior two years solidifying my decision to double-major in English literature and history. I had a full-tuition scholarship to the University of Wisconsin–Madison, worked part-time for the university honors program advising office, and was presently enjoying life as an exchange student at the University of Warwick in Coventry, England. I was taking a full load of classes, volunteering at a local elementary school, and had recently codirected some scenes of an amateur Shakespeare performance at a British pub. Back home in Wisconsin, I kept equally busy as a writing tutor, a Saint Vincent de Paul Society volunteer, submissions reviewer for the campus humanities journal, and an active member of the Catholic student organization. I went to Mass daily, slept very little, and was keeping my eyes peeled for a career that could integrate my eclectic mix of hobbies and passions, my personality, and my faith. I was struggling to find it.

I had too many interests, too little time, and a rapidly growing fear that my life could not contain everything I wanted to do and to be. Much like the history paper in front of me, I longed to organize the details of my life in a way that communicated something strong, clear, and meaningful. Scholarship committees expected this kind of clearsightedness. Employers wanted to know what I stood for and why they should hire me. I wanted to articulate my purpose, too—but choosing one path meant refusing another, and both actions made me hesitate. I feared that by choosing, I would lose a piece of myself through the cracks between my options, and I didn’t know if I would get it back.

After several minutes of mulling over my predicament in the library that afternoon, a new possibility quietly emerged. There was no warning, no context, no obvious trigger for it. It was simply there: consecrated life.

I was raised Catholic. My family went to Mass on Sundays, prayed before meals, and participated in our parish religious education program. I loved God as a child, but in my tweens and teens, my relationship with God grew more strained. I still believed in Him and pursued Him; I just wasn’t sure how He felt about me. During my first year of university, however, I was deeply impressed by the students I met at our campus Catholic center. They didn’t speak about Jesus as a historical person; they spoke about Him as someone they had just had an intimate conversation with. God wasn’t some distant, hazy figure to them but a Father who actively provided for His children, and whose providence they could see, feel, and touch. They were radiant, and I envied them. If God loved them enough to make them so keenly aware of His presence, why wasn’t He doing the same for me? I wondered what I was doing wrong—or what might be wrong with me.

My doubts pushed me to approach faith as something “I” needed to do better. I began to schedule more time for prayer, including daily Mass. I gave God room in my academic planner and hoped He would speak to me in the time I offered Him. Occasionally I thought I heard Him; most of the time I wasn’t sure. Prayer felt like a lot of guesswork. I just hoped God would give me points for effort. In the meantime, I scrambled to fill my planner with the rest of the things I needed to accomplish: school, work, extracurriculars, social life, exercise, grocery shopping, and sleep. Sometimes I felt as if I were holding all the components of my life in a flimsy paper bag that was about to burst at the seams. I was terrified of what would happen if the bag split.

So when the idea of consecrated life suddenly flashed through my mind in the Warwick College library, I was taken aback. This was not an invitation to schedule or accomplish something; it was an invitation to be someone. To be “consecrated” was to belong to God, to be set apart for Him and at His service. Could I do that? Like, officially? My pragmatic mind wrestled with the idea, unconvinced yet irresistibly compelled by it. It lured my mind away from academic prose and threw it into the realm of poetry. The thought of consecration did not connote a task or a goal; it whispered a promise.

I looked around the library. My peers were squinting into their books and computer screens, eager to digest a few more facts and formulas for their year-end exams. I should have been joining them, but instead I googled “consecrated life.” I found a blog written by a young woman who had just professed religious vows. And I read.

She was about my age: twenty-five years old to my twenty-one. She wrote about belonging to God and loving Him completely, with all her strength and being. She spoke of Christ as the unifying purpose and center of her life. Most powerfully of all, she seemed to be living what she wrote about. God’s love was not just an idea to her, but a tangible reality that inspired a radical response. Her reflection was short, but her words lit a fire in my heart.

I can still taste the freedom that surged forth from deep within my chest that day, relieving me of the load I was carrying. God knew the endless string of hopes, dreams, gifts, and limitations I held inside of me. He had put them there. He loved each one of them. More importantly, He loved me. I understood that the more I tried to obsessively plan and arrange (and rearrange) my life’s options, the more anxious I would grow and the further I would be from Him. Jesus was not just one part of my life. He was my life—its origin and its destination—and I would never fully know myself or my calling except through Him.

I left the library that day with no clear insights into my future. I didn’t even have a finished history paper. All I had was a new and unwavering assurance that God saw me, knew me, loved me, and had something in mind for me—possibly religious life. In the months that followed, I also began to realize that if I wanted to make room for a Love as great as this, I would need to let go of some things.

A short time later, one of my professors in Wisconsin emailed to ask if I had ever considered applying for a Rhodes Scholarship. She thought I had potential and was willing to offer me her mentorship, if I was interested. I swallowed—hard. This should have been the opportunity I was waiting for, but the level of competition I knew it would require threatened to throw me right back to where I was before: as an ambitious college junior making up life as I went, rather than a young woman beginning to discover and live more authentically the life God had already given me. I declined.

Not long after, a professor at Warwick called me into her office. “I enjoy your work,” she began as I took a seat across from her. “You understand what we do here. If you wanted to come back for graduate school, I would love to work with you.” I was moved by her offer. I also knew that if I said yes, it would be my ego speaking and not my true self. Slowly but surely, I was learning to detect the difference. There was a part of me who longed to define myself through advancement and achievement, but the real “me,” awakened by the Word of God, discerned that this was unnecessary. God knew me through and through. If I wanted to know myself and the meaning of my life, I could not hope to find them in a career or an award. I needed to pursue God and reject whatever might distract me from this pursuit. I needed to learn how to say no, so that I could say yes to the God who held my past, present, and future in His embrace.

This yes to God is the language and entire lexicon of poverty. When we speak of poverty, we often think about the no’s, but the no means absolutely nothing if it does not enable us to say yes to God from the depths of our being, with all that we are.

The power of this yes—and the many no’s it requires—is impossible to exaggerate in a world that urges us to keep all our options open, refrain from commitment, change our minds frequently, “go with the flow,” and scroll indeterminately through social media to relieve our FOMO. This is the yes of the major life commitments of marriage, consecrated life, and priestly ordination, as well as the small, day-to-day yesses we make for love of Christ.

Saint Paul, the patron of our Congregation, explains this dynamic best in his letter to the Philippians: “Have among yourselves the same mind that is in Christ Jesus, who, though He was in the form of God, did not regard equality with God something to be grasped; rather, He emptied Himself…” (Philippians 2:6–7). I prayed with this passage one afternoon while I was discerning whether to enter the Daughters of St. Paul. As I did, I found myself savoring the humility of Christ and the challenge He offers us. Jesus does not “grasp” and preach His identity as God, even though it rightly belongs to Him. Far from it. He is utterly unrecognizable on the Cross, not only as God but—thanks to the brutality of Roman beatings—as a human being as well. Why would the Son of God allow Himself to be subjected to such gross misrepresentation and misunderstanding? Because Jesus entrusted His identity, reputation, and entire being to His Father, and not to the world. His yes to God was so complete, He allowed God to raise Him up to His rightful place as Son and Savior in His own time.

This is poverty.

In the consecrated life, our identity is not composed of the things we do, the roles we have been given, the opinions others have of us, or even the attitudes we have about ourselves. We may be tempted to cling to one or all of these things in an effort to tell the world (or ourselves) who we are, but this possessive attitude distracts our gaze from where it ought to be—on God the Father. Like Jesus, we must reserve our yes for God and the daily invitations He offers us to grow in love, patience, trust, humility, and hope. We must also have the courage to offer a full-throated no to every other offer. We cannot “have it all” in this world (sorry, Jason Mraz), nor should we want to, because if we strive for everything, we will end up with nothing. On the other hand, if we view every situation as an opportunity to choose what will best help us love and imitate Christ, we will choose All—and this choice will be all the more powerful because of every no we utter in the process.

The Language of Chastity

My first visit to a convent was in the quaint village of Brownshill, England. I was not discerning a religious vocation at the time; I just wanted a weekend to pray, rest, and see another part of England. I carpooled with some friends to get there, and as our van rolled over the gentle, winding slopes of the British countryside, I marveled at the world we were entering. Away from the bustle of the university campus, this hilltop Bernardine Cistercian monastery felt like something out of a Wordsworth poem. I was enchanted.

One morning that weekend, after celebrating Mass together, my friends, some of the sisters, and I knelt in the convent chapel for a few extra minutes of silent prayer. One by one, everyone stood up and left. Except me.

As I knelt in front of the tabernacle where the Blessed Sacrament, the Real Presence of Christ, was reserved, I was suddenly acutely aware of the Lord’s presence. Jesus was physically here in front of me. And He wasn’t just sitting here; He was dynamic and alive. I was drawn to Him, forcefully yet gently, and in the ineffable mystery of that moment, I understood that I was feeling some of the weight of God’s endless love. It pressed upon me, and I didn’t resist. I could not fight it, even if I wanted to. I was in a state of contradiction, both at peace and not at peace, overwhelmed by the passion that surrounded me, yet calm enough to remain where I was. I was loved. Immensely loved. Fearfully loved. And through the terrifying beauty of such love, a word of Scripture suddenly emerged and pressed itself against the ear of my heart: “Love others as I have loved you.”

This was the first time I grasped the sheer impossibility of God’s command. How could I love as perfectly as God loved?

I don’t know how long I was in the chapel, though I do remember leaving in somewhat of a daze. As I pushed open the chapel doors, I saw a sister standing in the hall outside, talking to one of my friends. I looked at both of them with a mix of reverence, wonder, and fear. God loved them immensely. And me? What could I do? Say? Everything felt so insufficient, and I stood there dumbly, a little frozen by the hopelessness of it all.

As my friend walked away, the sister looked over at me and smiled. “You really love the Lord, don’t you?” My face turned as red as my ginger hair. Had she seen me in the chapel? I wondered. What had she seen?

I returned her gaze sheepishly and let out a lame, but honest response: “I… try to.”

Sister smiled wider. “Don’t try so hard.”

I am a chronic perfectionist—which is precisely why I trembled my way out of the Brownshill chapel that morning. God had given me an impossible command, and the certainty of failure stopped me in my tracks. That sister’s words, however—“Don’t try so hard”—gently redirected my gaze from my obvious human weakness to the abundant generosity of God. God was not asking me to compete with His love; He was inviting me to accept and surrender to it. He wasn’t calling me to love others for Him, but with Him.

Years later, as I began to pray more intentionally about my vocation, my introspective anxiety returned with a vengeance. Despite my attraction to the religious life and to the Daughters of St. Paul, I just wasn’t convinced that such a radical choice was… well, necessary. How did I know, without a doubt, that God really wanted this from me? Wasn’t it arrogant to think that God would ask me to belong to Him and communicate His love to the world? As the months went by, I began to pray for an unmistakable sign that I was called to be a Daughter of St. Paul. Prudence (not love) told me that I could not say yes until I had absolute clarity.

Such “clarity” came almost one year later through an unexpected phone call: a friend from my parish young adult group wanted to ask me out. This was not an earth-shattering question, but to my ears, it sounded like an ultimatum. For some reason, I had assumed God would clear up my confusion about the future before any dating possibilities appeared on my horizon. And now? Now I had to concretely choose something without the clarity and assurance I had prayed for. I didn’t like it.

I was on my way home to visit family in Michigan when the call came through. Oddly grateful for my lack of availability, I postponed my friend’s invitation and boarded my flight with even more on my mind than I had anticipated. When I reached Detroit, I spent my layover pacing the airport from Terminal A to Terminal C, and back again, wondering what to say when I called him back.

I wanted to say yes. Dating felt safer, more comfortable, and frankly more normal than religious life. I was excited about the possibility of falling in love and didn’t want to miss this chance. And yet… somehow, the door to religious life still felt open. As I paced and prayed with my roller luggage, I began to realize that God wasn’t going to clear things up for me. He was offering me a choice—and He wanted me to choose.

Until that moment, I had been willing to enter the Daughters of St. Paul as long as I knew that this was what God wanted. If it wasn’t necessary, I wasn’t going to do it. What I hadn’t considered was that God might invite me to be part of the decision. God was opening two doors for me, religious life and marriage, and was patiently waiting for me to step through one of them. Moved by God’s gentleness, I realized deep down that I wanted to say yes to Him through the vows of religious life, and that I longed for His yes in return. Perhaps the vows were unnecessary and over-the-top—but then again, so was God’s love for me.

I applied to the Daughters of St. Paul a few weeks later. As I did, my obsession with discovering the will of God faded into a deeper understanding that God rarely reveals His will to us in full color and graphic detail. He leads us step-by-step and invites us to follow. He calls and leaves us free to respond. The choice is always ours, and so is the joy of making a choice not for the sake of security or clarity, but for love of God.

The Language of Obedience

Blessed James Alberione, the founder of our Congregation, once wrote that “obedience is the greatest freedom.” A paradox? Perhaps. But at age nineteen, I learned that it could also be true.

Midway through my first semester of college, I was diagnosed with anorexia. The disease had been slowly and insidiously attacking my mind and my body for nearly a year, but I had not recognized it—at least not directly. Most sufferers don’t.

I was obliquely aware that something was happening, of course. In the year leading up to my diagnosis, I had gradually stopped eating and my mental health was deteriorating. The smallest inconvenience was powerful enough to send me spiraling into a depression or kindle a rage so intense I barely managed to hide it away. As friends and family questioned my apparent weight loss and troubled mood, I assured them I was fine, while secretly holding to the conviction that I needed to be better, and thinner, than I was.

Eventually I ended up in the university medical center and was gently coerced into seeing three different specialists in between my freshman classes. They gave me one goal: to try to gain back one pound per week. Three weeks later, I had lost another pound. As my doctor logged the disappointing weigh-in on his clipboard, he turned to me with a suggestion that took my breath away. “You might want to take the next semester off of school to work on your health.” I was stunned. To quit school was to admit I had a problem, and I still didn’t fully believe that something was wrong.

“Absolutely not,” I fired back. “I can do this. It’s just…” I trailed off, lost in the effort to verbalize my frustration. “I thought I was supposed to listen to my body, and my body is never hungry. So why eat? If I’m really supposed to eat more, why isn’t my body telling me that?" Each question dripped with anger, fear, and my recurring doubt that anything was even wrong in the first place. They were not really questions about eating, but questions about what to believe.

“Your body isn’t hungry because you’re not eating,” the doctor replied. I stared blankly at him, turning the paradox over in my mind with a mix of curiosity and disgust. He went on. “You have to teach your brain how to be hungry again. You’ve starved it for so long that it’s no longer responding the way it’s supposed to respond. You can’t wait to be hungry before you start eating; you have to eat first. Then you will feel hungry.”

This conversation was the turning point in my recovery from anorexia—and in many ways, it has become a foundational metaphor for my relationship with God as well. Beneath the doctor’s words was something more than an invitation to eat. It was a call to obey a truth that I didn’t fully believe yet, with the promise that I would believe—and heal—if I dared to live it anyway. It was my own personal experience of Jesus calling me out of the boat to walk on water toward Him. The waves threatened to overwhelm me, and yet the voice of our Lord—“Come”—was unmistakable and had the power to help me walk.

When I left the medical office, I bought a Venti Starbucks chocolate banana smoothie and muscled it down my throat in obedience. I was terrified, but deep down, I knew that obedience to my doctor’s orders was my salvation, even as my twisted emotions and disordered reasoning told me otherwise.

A few months later, I left campus for a weekend to visit a friend in another city. She had taken up ballroom dancing and invited me to go to salsa practice with her. Open to the adventure, I borrowed her dress pants and joined her in the middle of the dance floor, mimicking the instructor’s footing and watching my movements in the mirror to check my accuracy. Suddenly I stopped. I locked eyes with myself in the mirror for the first time in a long time, and I finally saw what everyone else had been seeing: how thin, and how sick, I really was. It was the first time I really believed the truth of my illness, and I instinctively knew this gift of sight was the fruit of the past several months of slow, tedious acts of obedience to my doctor and faith in the promise of a healthier life. I had been a prisoner of my illness and disordered thinking, but obedience to the truth was setting me free.

In the spiritual life, the call to obedience is ultimately a call to listen—deeply, honestly, and with humility—in order to know and live in the Truth. As Christians, we believe in a God who continually speaks to us through Scripture, the life and teachings of the Church, and the events of daily life. If we want to know God as He is (and ourselves as we really are, since we are made in His image), we must be attentive to the ways God reveals Himself to us and follow the plan of life that He proposes. This often means trusting God and His commandments even when they don’t immediately make sense to us. After all, God transcends our human ways of knowing. His Word is not designed to fit comfortably within our current lifestyle, emotional state, and flawed human reasoning. Quite the opposite. God speaks to release us from our limitations, so that by trusting and living His Word, we might have a share in His life, sentiments, and knowledge. God always calls us to Himself, and that means traveling beyond ourselves. The more we follow God’s call across the tight boundaries we draw around our life, the more we discover that His Word is not just a simple commandment or teaching. The Word is Jesus Himself, who lives in us through our obedience. As our lives increasingly mirror the life of Jesus, we learn to see Him as He is and ourselves as we really are. And this truth sets us free.

When I entered the Daughters of St. Paul in my mid-twenties, I arrived with tight personal boundaries and stereotypical expectations. I was eager to experience God through the life, prayer, and mission of my new community and didn’t think I would have to look too hard to find Him. As I got to know the three women I had entered with, however, I was taken aback by how different we were—and how easy it was for us to get on each other’s nerves. All four of us had entered the community with different sets of life experiences, family cultures, and expectations about religious life that we were individually trying to “obey.” They didn’t always dovetail, and misunderstandings and tensions seemed to abound.

After several months of this, I was suddenly knocked down by a wave of homesickness. I missed my people and my friends, whom I naturally understood and got along with. What was the Lord asking of me here? I had followed Him into the convent, and now He seemed to have left me at the doorstep. After one particularly difficult day, I walked into our chapel for my daily hour of Adoration and started fuming. It wasn’t much of a prayer, more of a complaint-ridden monologue. I didn’t expect Jesus to respond, and part of me wondered if He was even listening. I was stunned into silence, therefore, when the Lord interrupted my prayer with a question of His own: “What do you need that I have not provided for you? Tell me what you need, and I will give it.”

Rarely have I heard Jesus speak to me so clearly in prayer as He did that day. I did not hear Him with my ears, but His question cut through my tangled, emotion-laden thoughts with unmistakable precision. I paused and gingerly considered Jesus’ question. What struck me the most was the way He asked it. Jesus’ words weren’t huffy, as I might have said them. (“Seriously, Amanda? What do you still need that I haven’t given you already?”) Rather, He asked with longing and a desire to fulfill: Tell me what you need. I revisited my grumbling to figure out what, exactly, I needed from Him. In the end, I found nothing. I had everything I needed; just not everything I wanted. And what I especially wanted was a group of women I could get along with a little more easily.

Jesus then offered me two more words: “Trust me.” Through them, I understood that Jesus was revealing Himself to me through these women. He was loving me in ways I wasn’t used to being loved, through women whose hearts were different from my own—and yet very much the same. It was not enough for me to experience love in the way I was “used to” experiencing it. Jesus wanted my heart to resemble His own, and to do this, He needed to stretch it. Every moment of every day was a new opportunity to obey His invitation to give and receive love in new ways, beyond the tight boundaries of my own culture, upbringing, and understanding. I could dismiss the things I didn’t understand as obstacles to following God, or I could believe God was present in the very people and moments that perplexed me the most, and listen for His invitation to love Him there and receive His love in new and unexpected ways.

We often think of the will of God as something that is “out there” for us to find. But God does not hide His will from us. It is always here, taking concrete form in the situations, people, history, and circumstances that surround us. This is the context in which God urges us to “step out of the boat” of our current understanding, trust in the truth of His Word, and follow Him. When we do so, He lifts the veil on His promise to be with us always and allows us to glimpse where and how He is at work in our lives. And in the same breath, He beckons us to follow Him higher, further, and deeper still.

The Language of Love

The Daughters of St. Paul have been singing and recording albums for years, as part of our mission to proclaim Christ through media. A couple years ago, my superiors asked if I would join the choir. The request took me by surprise. I had limited talent and no experience to speak of, unless you count car karaoke. I was willing, but skeptical.

Thankfully, one of my sisters saw my plight and offered to give me some singing lessons and breathing tips. As we met in her office one afternoon, she helped me with my posture, led me through vocal warm-ups, and taught me how to project my voice from the right part of my face. I exhaled several notes at a medium volume while carefully eyeing her office window and the hallway outside.

“Sing out!” she gently encouraged.

“I’m really not a good singer,” I confessed, turning away from the window and meeting her gaze. “I don’t know why they asked me to do this.”

She nodded in understanding. “I felt the same way when they first asked me to join the choir. I’m not confident in my voice either. But if the sisters chose you, they obviously see something you don’t see.”

There it was again: the call to trust, to obey, to step out of the boat and meet Jesus in a place I had never intended to go.

My sister continued, as if she had read my thoughts. “I’ve come to realize that singing is ultimately an act of love. We can’t hear our voice the way others hear it; it resonates differently in our ears than it does for them. We sing, not because we want to know what we sound like or how good we are, but because we offer the gift of our voice to the Lord and trust that He will use it as He desires. This is our gift to Him and to His People—and if God is going to use it, we have to let go of what we think about ourselves.”

It is easy to harbor anxiety about how others see and respond to us. It is easy to make comparisons and judgments; to internalize the praise and the doubts that others voice about us; and to calculate whether the return we get is worth the effort we put into trying to communicate something to the world. It is much harder to “sing out” in love without looking for something in return. Nevertheless, this is precisely the kind of singing Christ models for us through His life of poverty, chastity, and obedience. The life of Christ is a song of selfless love and freedom, and it is taken up by those who have nothing to lose because they are secure in the knowledge that they are children of God. If we want to learn this song and hear its melody in the background of our lives, we have to practice singing it: not by our own efforts, but in communion with the Holy Spirit who has promised to teach us His language of love and attune our hearts to its everlasting cadence.

Our world needs more singers. It needs men and women who are not afraid to give God more than what they think others will understand, so that others may see in them a reflection of the God beyond all understanding. The world needs the gift of our voices and our lives, so that it might find in us—as my sisters and I have found in Christ—a language of life through which it, too, can lift the fullness of its heart to God.

I had just unscrewed the gas cap of our Pontiac Montana when the hot August wind lunged after my veil and whipped it across my face. Again. I was in my second month of vowed religious life and still adjusting to many things, including my new relationship with nature. I gently brushed my veil as far away from the gas pump as possible and began to fill our tank.

Minutes later, a car pulled up at the neighboring pump. A middle-age man stepped out, saw me fighting to keep my veil from wrapping around the fuel hose, and walked in my direction. My stomach danced. Veil or no veil, I am an introvert; and now, thanks to the infinite creativity of God, I had become an introvert who stood out in a crowd.

“Hey! I have a question for you,” the man asked. He took a few steps closer. “What made you want to do that?”

I knew he wasn’t asking about the gas fill-up.

I paused for a moment as a million answers welled up in my mind and in my heart. Lord, what do I say? Where do I begin? Suddenly every answer vanished—except one. The right one. The only one. I looked him in the eyes and gave a shy smile: “Because I’m in love.”

My parents named me “Amanda,” which is Latin for “she who must be loved.” It is a name that is much easier to carry around with me than it is to live out. In fact, the first time I heard what it means, I resisted the definition. It sounded arrogant to my adolescent ears. I must be loved? Really?

The verb “love” has a necessity and an urgency about it. God actually commands it: “You shall love the Lord your God.” When I heard these words as a young Catholic, I wondered if love could really be commanded. I further wondered how I should respond to this command when I didn’t feel any special affection toward God. He was a distant, bearded figure who asked us to do things and never seemed to offer any feedback—at least not in the way my parents and teachers did. Even if I could conjure up some feelings of love for Him, when would I feel Him love me back?

Some years ago, an astute five-year-old reminded me that love was never meant to be analyzed or dissected like this. Children don’t ponder the “command” of love, how necessary love is, or how best to do it. They simply love. I watched this happen during a mission trip to Texas, as my sisters and I spent an evening at the home of good friends of our community. Their young daughter wanted to show me something in the backyard. I followed her outside, and after taking a hard look at whatever she was pointing at, we both were suddenly distracted by the immense ink-black, diamond-studded Texas sky that stretched over our heads. As we cranked our heads back in wonder, the little girl spontaneously uttered three small words: “I love God!” Then she stooped to the ground and started digging a hole in her mother’s flower beds. “I love God, too,” I whispered after her, but it sounded pathetic rolling off my lips. She had the spontaneity and the heart; I was stumbling after her, trying to keep up.

Children seem to have a natural capacity to speak to God and raise their hearts to Him. How do we all seem to lose this as we grow up? Or perhaps more importantly, how do we get it back?

My life as a religious sister is about learning this language of God—a language not of words, but of life. God’s word to us is not a jumble of letters and sounds, but a person: Jesus Christ. As Daughters of Saint Paul, we live our lives in relationship with this Word. We encounter Jesus speaking to us in Scripture, in the Church, and in our everyday experience of being human, and we continually bring our lives into conformity with His so that we, too, might speak of God. Of course, none of us speak this divine language perfectly. The “accent” of our failures and limitations betrays our lack of fluency. But God is generous and eager to teach. His desire to call forth the image of His Son in each one of us is a bit like Gandalf’s approach to Bilbo in The Hobbit, when Gandalf knocks on Bilbo’s door with a startling invitation: “I am looking for someone to share in an adventure that I am arranging, and it’s very difficult to find anyone.” God is always knocking at our door. We’re just not always home to hear it.

Over the years, I have learned to recognize God’s “knocks” as ardent but subtle, filled with respect for my free will and love for my humanity. God has knocked on my pursuit of success and achievement, my relationships with others, and the situations that had me most convinced that He was absent. And with each knock, He has invited me to step beyond the constricted Hobbit hole of human understanding and convenience and learn to speak the language of His love—which is nothing less than the poor, chaste, and obedient life of Christ.

I professed the religious vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience for the first time in June of 2019. In doing so, I said yes to the adventure of following Christ more closely and immersing myself in the language of God’s love. Jesus has been my Way, Truth, and Life on every twist and turn of this journey, and every day He offers me another glimpse of what it means to love and to be “in love”—which is to say, to be “in Him.”

The Language of Poverty

The books made an unceremonious thud as they hit the library table. My backpack was next, followed by a laptop and a thermos full of coffee. These would be my companions for the next several hours. My mind was already churning as I pulled up a chair and began to brainstorm several possible directions for my history paper. Minutes later, my fingers began their rhythmic scramble across my keyboard, punching out the results of my research on the political and gendered leanings of sixteenth-century British periodicals. After an hour of writing, my brain began to drift more pensively over the task at hand; then it stopped entirely.

What was I doing?

It was my junior year of college and my postgraduate dreams were supposedly at their peak. I had spent the prior two years solidifying my decision to double-major in English literature and history. I had a full-tuition scholarship to the University of Wisconsin–Madison, worked part-time for the university honors program advising office, and was presently enjoying life as an exchange student at the University of Warwick in Coventry, England. I was taking a full load of classes, volunteering at a local elementary school, and had recently codirected some scenes of an amateur Shakespeare performance at a British pub. Back home in Wisconsin, I kept equally busy as a writing tutor, a Saint Vincent de Paul Society volunteer, submissions reviewer for the campus humanities journal, and an active member of the Catholic student organization. I went to Mass daily, slept very little, and was keeping my eyes peeled for a career that could integrate my eclectic mix of hobbies and passions, my personality, and my faith. I was struggling to find it.

I had too many interests, too little time, and a rapidly growing fear that my life could not contain everything I wanted to do and to be. Much like the history paper in front of me, I longed to organize the details of my life in a way that communicated something strong, clear, and meaningful. Scholarship committees expected this kind of clearsightedness. Employers wanted to know what I stood for and why they should hire me. I wanted to articulate my purpose, too—but choosing one path meant refusing another, and both actions made me hesitate. I feared that by choosing, I would lose a piece of myself through the cracks between my options, and I didn’t know if I would get it back.

After several minutes of mulling over my predicament in the library that afternoon, a new possibility quietly emerged. There was no warning, no context, no obvious trigger for it. It was simply there: consecrated life.

I was raised Catholic. My family went to Mass on Sundays, prayed before meals, and participated in our parish religious education program. I loved God as a child, but in my tweens and teens, my relationship with God grew more strained. I still believed in Him and pursued Him; I just wasn’t sure how He felt about me. During my first year of university, however, I was deeply impressed by the students I met at our campus Catholic center. They didn’t speak about Jesus as a historical person; they spoke about Him as someone they had just had an intimate conversation with. God wasn’t some distant, hazy figure to them but a Father who actively provided for His children, and whose providence they could see, feel, and touch. They were radiant, and I envied them. If God loved them enough to make them so keenly aware of His presence, why wasn’t He doing the same for me? I wondered what I was doing wrong—or what might be wrong with me.

My doubts pushed me to approach faith as something “I” needed to do better. I began to schedule more time for prayer, including daily Mass. I gave God room in my academic planner and hoped He would speak to me in the time I offered Him. Occasionally I thought I heard Him; most of the time I wasn’t sure. Prayer felt like a lot of guesswork. I just hoped God would give me points for effort. In the meantime, I scrambled to fill my planner with the rest of the things I needed to accomplish: school, work, extracurriculars, social life, exercise, grocery shopping, and sleep. Sometimes I felt as if I were holding all the components of my life in a flimsy paper bag that was about to burst at the seams. I was terrified of what would happen if the bag split.

So when the idea of consecrated life suddenly flashed through my mind in the Warwick College library, I was taken aback. This was not an invitation to schedule or accomplish something; it was an invitation to be someone. To be “consecrated” was to belong to God, to be set apart for Him and at His service. Could I do that? Like, officially? My pragmatic mind wrestled with the idea, unconvinced yet irresistibly compelled by it. It lured my mind away from academic prose and threw it into the realm of poetry. The thought of consecration did not connote a task or a goal; it whispered a promise.

I looked around the library. My peers were squinting into their books and computer screens, eager to digest a few more facts and formulas for their year-end exams. I should have been joining them, but instead I googled “consecrated life.” I found a blog written by a young woman who had just professed religious vows. And I read.

She was about my age: twenty-five years old to my twenty-one. She wrote about belonging to God and loving Him completely, with all her strength and being. She spoke of Christ as the unifying purpose and center of her life. Most powerfully of all, she seemed to be living what she wrote about. God’s love was not just an idea to her, but a tangible reality that inspired a radical response. Her reflection was short, but her words lit a fire in my heart.

I can still taste the freedom that surged forth from deep within my chest that day, relieving me of the load I was carrying. God knew the endless string of hopes, dreams, gifts, and limitations I held inside of me. He had put them there. He loved each one of them. More importantly, He loved me. I understood that the more I tried to obsessively plan and arrange (and rearrange) my life’s options, the more anxious I would grow and the further I would be from Him. Jesus was not just one part of my life. He was my life—its origin and its destination—and I would never fully know myself or my calling except through Him.

I left the library that day with no clear insights into my future. I didn’t even have a finished history paper. All I had was a new and unwavering assurance that God saw me, knew me, loved me, and had something in mind for me—possibly religious life. In the months that followed, I also began to realize that if I wanted to make room for a Love as great as this, I would need to let go of some things.

A short time later, one of my professors in Wisconsin emailed to ask if I had ever considered applying for a Rhodes Scholarship. She thought I had potential and was willing to offer me her mentorship, if I was interested. I swallowed—hard. This should have been the opportunity I was waiting for, but the level of competition I knew it would require threatened to throw me right back to where I was before: as an ambitious college junior making up life as I went, rather than a young woman beginning to discover and live more authentically the life God had already given me. I declined.

Not long after, a professor at Warwick called me into her office. “I enjoy your work,” she began as I took a seat across from her. “You understand what we do here. If you wanted to come back for graduate school, I would love to work with you.” I was moved by her offer. I also knew that if I said yes, it would be my ego speaking and not my true self. Slowly but surely, I was learning to detect the difference. There was a part of me who longed to define myself through advancement and achievement, but the real “me,” awakened by the Word of God, discerned that this was unnecessary. God knew me through and through. If I wanted to know myself and the meaning of my life, I could not hope to find them in a career or an award. I needed to pursue God and reject whatever might distract me from this pursuit. I needed to learn how to say no, so that I could say yes to the God who held my past, present, and future in His embrace.

This yes to God is the language and entire lexicon of poverty. When we speak of poverty, we often think about the no’s, but the no means absolutely nothing if it does not enable us to say yes to God from the depths of our being, with all that we are.

The power of this yes—and the many no’s it requires—is impossible to exaggerate in a world that urges us to keep all our options open, refrain from commitment, change our minds frequently, “go with the flow,” and scroll indeterminately through social media to relieve our FOMO. This is the yes of the major life commitments of marriage, consecrated life, and priestly ordination, as well as the small, day-to-day yesses we make for love of Christ.

Saint Paul, the patron of our Congregation, explains this dynamic best in his letter to the Philippians: “Have among yourselves the same mind that is in Christ Jesus, who, though He was in the form of God, did not regard equality with God something to be grasped; rather, He emptied Himself…” (Philippians 2:6–7). I prayed with this passage one afternoon while I was discerning whether to enter the Daughters of St. Paul. As I did, I found myself savoring the humility of Christ and the challenge He offers us. Jesus does not “grasp” and preach His identity as God, even though it rightly belongs to Him. Far from it. He is utterly unrecognizable on the Cross, not only as God but—thanks to the brutality of Roman beatings—as a human being as well. Why would the Son of God allow Himself to be subjected to such gross misrepresentation and misunderstanding? Because Jesus entrusted His identity, reputation, and entire being to His Father, and not to the world. His yes to God was so complete, He allowed God to raise Him up to His rightful place as Son and Savior in His own time.

This is poverty.

In the consecrated life, our identity is not composed of the things we do, the roles we have been given, the opinions others have of us, or even the attitudes we have about ourselves. We may be tempted to cling to one or all of these things in an effort to tell the world (or ourselves) who we are, but this possessive attitude distracts our gaze from where it ought to be—on God the Father. Like Jesus, we must reserve our yes for God and the daily invitations He offers us to grow in love, patience, trust, humility, and hope. We must also have the courage to offer a full-throated no to every other offer. We cannot “have it all” in this world (sorry, Jason Mraz), nor should we want to, because if we strive for everything, we will end up with nothing. On the other hand, if we view every situation as an opportunity to choose what will best help us love and imitate Christ, we will choose All—and this choice will be all the more powerful because of every no we utter in the process.

The Language of Chastity

My first visit to a convent was in the quaint village of Brownshill, England. I was not discerning a religious vocation at the time; I just wanted a weekend to pray, rest, and see another part of England. I carpooled with some friends to get there, and as our van rolled over the gentle, winding slopes of the British countryside, I marveled at the world we were entering. Away from the bustle of the university campus, this hilltop Bernardine Cistercian monastery felt like something out of a Wordsworth poem. I was enchanted.

One morning that weekend, after celebrating Mass together, my friends, some of the sisters, and I knelt in the convent chapel for a few extra minutes of silent prayer. One by one, everyone stood up and left. Except me.

As I knelt in front of the tabernacle where the Blessed Sacrament, the Real Presence of Christ, was reserved, I was suddenly acutely aware of the Lord’s presence. Jesus was physically here in front of me. And He wasn’t just sitting here; He was dynamic and alive. I was drawn to Him, forcefully yet gently, and in the ineffable mystery of that moment, I understood that I was feeling some of the weight of God’s endless love. It pressed upon me, and I didn’t resist. I could not fight it, even if I wanted to. I was in a state of contradiction, both at peace and not at peace, overwhelmed by the passion that surrounded me, yet calm enough to remain where I was. I was loved. Immensely loved. Fearfully loved. And through the terrifying beauty of such love, a word of Scripture suddenly emerged and pressed itself against the ear of my heart: “Love others as I have loved you.”

This was the first time I grasped the sheer impossibility of God’s command. How could I love as perfectly as God loved?

I don’t know how long I was in the chapel, though I do remember leaving in somewhat of a daze. As I pushed open the chapel doors, I saw a sister standing in the hall outside, talking to one of my friends. I looked at both of them with a mix of reverence, wonder, and fear. God loved them immensely. And me? What could I do? Say? Everything felt so insufficient, and I stood there dumbly, a little frozen by the hopelessness of it all.

As my friend walked away, the sister looked over at me and smiled. “You really love the Lord, don’t you?” My face turned as red as my ginger hair. Had she seen me in the chapel? I wondered. What had she seen?

I returned her gaze sheepishly and let out a lame, but honest response: “I… try to.”

Sister smiled wider. “Don’t try so hard.”

I am a chronic perfectionist—which is precisely why I trembled my way out of the Brownshill chapel that morning. God had given me an impossible command, and the certainty of failure stopped me in my tracks. That sister’s words, however—“Don’t try so hard”—gently redirected my gaze from my obvious human weakness to the abundant generosity of God. God was not asking me to compete with His love; He was inviting me to accept and surrender to it. He wasn’t calling me to love others for Him, but with Him.

Years later, as I began to pray more intentionally about my vocation, my introspective anxiety returned with a vengeance. Despite my attraction to the religious life and to the Daughters of St. Paul, I just wasn’t convinced that such a radical choice was… well, necessary. How did I know, without a doubt, that God really wanted this from me? Wasn’t it arrogant to think that God would ask me to belong to Him and communicate His love to the world? As the months went by, I began to pray for an unmistakable sign that I was called to be a Daughter of St. Paul. Prudence (not love) told me that I could not say yes until I had absolute clarity.

Such “clarity” came almost one year later through an unexpected phone call: a friend from my parish young adult group wanted to ask me out. This was not an earth-shattering question, but to my ears, it sounded like an ultimatum. For some reason, I had assumed God would clear up my confusion about the future before any dating possibilities appeared on my horizon. And now? Now I had to concretely choose something without the clarity and assurance I had prayed for. I didn’t like it.

I was on my way home to visit family in Michigan when the call came through. Oddly grateful for my lack of availability, I postponed my friend’s invitation and boarded my flight with even more on my mind than I had anticipated. When I reached Detroit, I spent my layover pacing the airport from Terminal A to Terminal C, and back again, wondering what to say when I called him back.

I wanted to say yes. Dating felt safer, more comfortable, and frankly more normal than religious life. I was excited about the possibility of falling in love and didn’t want to miss this chance. And yet… somehow, the door to religious life still felt open. As I paced and prayed with my roller luggage, I began to realize that God wasn’t going to clear things up for me. He was offering me a choice—and He wanted me to choose.

Until that moment, I had been willing to enter the Daughters of St. Paul as long as I knew that this was what God wanted. If it wasn’t necessary, I wasn’t going to do it. What I hadn’t considered was that God might invite me to be part of the decision. God was opening two doors for me, religious life and marriage, and was patiently waiting for me to step through one of them. Moved by God’s gentleness, I realized deep down that I wanted to say yes to Him through the vows of religious life, and that I longed for His yes in return. Perhaps the vows were unnecessary and over-the-top—but then again, so was God’s love for me.

I applied to the Daughters of St. Paul a few weeks later. As I did, my obsession with discovering the will of God faded into a deeper understanding that God rarely reveals His will to us in full color and graphic detail. He leads us step-by-step and invites us to follow. He calls and leaves us free to respond. The choice is always ours, and so is the joy of making a choice not for the sake of security or clarity, but for love of God.

The Language of Obedience

Blessed James Alberione, the founder of our Congregation, once wrote that “obedience is the greatest freedom.” A paradox? Perhaps. But at age nineteen, I learned that it could also be true.

Midway through my first semester of college, I was diagnosed with anorexia. The disease had been slowly and insidiously attacking my mind and my body for nearly a year, but I had not recognized it—at least not directly. Most sufferers don’t.

I was obliquely aware that something was happening, of course. In the year leading up to my diagnosis, I had gradually stopped eating and my mental health was deteriorating. The smallest inconvenience was powerful enough to send me spiraling into a depression or kindle a rage so intense I barely managed to hide it away. As friends and family questioned my apparent weight loss and troubled mood, I assured them I was fine, while secretly holding to the conviction that I needed to be better, and thinner, than I was.

Eventually I ended up in the university medical center and was gently coerced into seeing three different specialists in between my freshman classes. They gave me one goal: to try to gain back one pound per week. Three weeks later, I had lost another pound. As my doctor logged the disappointing weigh-in on his clipboard, he turned to me with a suggestion that took my breath away. “You might want to take the next semester off of school to work on your health.” I was stunned. To quit school was to admit I had a problem, and I still didn’t fully believe that something was wrong.

“Absolutely not,” I fired back. “I can do this. It’s just…” I trailed off, lost in the effort to verbalize my frustration. “I thought I was supposed to listen to my body, and my body is never hungry. So why eat? If I’m really supposed to eat more, why isn’t my body telling me that?" Each question dripped with anger, fear, and my recurring doubt that anything was even wrong in the first place. They were not really questions about eating, but questions about what to believe.

“Your body isn’t hungry because you’re not eating,” the doctor replied. I stared blankly at him, turning the paradox over in my mind with a mix of curiosity and disgust. He went on. “You have to teach your brain how to be hungry again. You’ve starved it for so long that it’s no longer responding the way it’s supposed to respond. You can’t wait to be hungry before you start eating; you have to eat first. Then you will feel hungry.”

This conversation was the turning point in my recovery from anorexia—and in many ways, it has become a foundational metaphor for my relationship with God as well. Beneath the doctor’s words was something more than an invitation to eat. It was a call to obey a truth that I didn’t fully believe yet, with the promise that I would believe—and heal—if I dared to live it anyway. It was my own personal experience of Jesus calling me out of the boat to walk on water toward Him. The waves threatened to overwhelm me, and yet the voice of our Lord—“Come”—was unmistakable and had the power to help me walk.

When I left the medical office, I bought a Venti Starbucks chocolate banana smoothie and muscled it down my throat in obedience. I was terrified, but deep down, I knew that obedience to my doctor’s orders was my salvation, even as my twisted emotions and disordered reasoning told me otherwise.

A few months later, I left campus for a weekend to visit a friend in another city. She had taken up ballroom dancing and invited me to go to salsa practice with her. Open to the adventure, I borrowed her dress pants and joined her in the middle of the dance floor, mimicking the instructor’s footing and watching my movements in the mirror to check my accuracy. Suddenly I stopped. I locked eyes with myself in the mirror for the first time in a long time, and I finally saw what everyone else had been seeing: how thin, and how sick, I really was. It was the first time I really believed the truth of my illness, and I instinctively knew this gift of sight was the fruit of the past several months of slow, tedious acts of obedience to my doctor and faith in the promise of a healthier life. I had been a prisoner of my illness and disordered thinking, but obedience to the truth was setting me free.

In the spiritual life, the call to obedience is ultimately a call to listen—deeply, honestly, and with humility—in order to know and live in the Truth. As Christians, we believe in a God who continually speaks to us through Scripture, the life and teachings of the Church, and the events of daily life. If we want to know God as He is (and ourselves as we really are, since we are made in His image), we must be attentive to the ways God reveals Himself to us and follow the plan of life that He proposes. This often means trusting God and His commandments even when they don’t immediately make sense to us. After all, God transcends our human ways of knowing. His Word is not designed to fit comfortably within our current lifestyle, emotional state, and flawed human reasoning. Quite the opposite. God speaks to release us from our limitations, so that by trusting and living His Word, we might have a share in His life, sentiments, and knowledge. God always calls us to Himself, and that means traveling beyond ourselves. The more we follow God’s call across the tight boundaries we draw around our life, the more we discover that His Word is not just a simple commandment or teaching. The Word is Jesus Himself, who lives in us through our obedience. As our lives increasingly mirror the life of Jesus, we learn to see Him as He is and ourselves as we really are. And this truth sets us free.

When I entered the Daughters of St. Paul in my mid-twenties, I arrived with tight personal boundaries and stereotypical expectations. I was eager to experience God through the life, prayer, and mission of my new community and didn’t think I would have to look too hard to find Him. As I got to know the three women I had entered with, however, I was taken aback by how different we were—and how easy it was for us to get on each other’s nerves. All four of us had entered the community with different sets of life experiences, family cultures, and expectations about religious life that we were individually trying to “obey.” They didn’t always dovetail, and misunderstandings and tensions seemed to abound.

After several months of this, I was suddenly knocked down by a wave of homesickness. I missed my people and my friends, whom I naturally understood and got along with. What was the Lord asking of me here? I had followed Him into the convent, and now He seemed to have left me at the doorstep. After one particularly difficult day, I walked into our chapel for my daily hour of Adoration and started fuming. It wasn’t much of a prayer, more of a complaint-ridden monologue. I didn’t expect Jesus to respond, and part of me wondered if He was even listening. I was stunned into silence, therefore, when the Lord interrupted my prayer with a question of His own: “What do you need that I have not provided for you? Tell me what you need, and I will give it.”

Rarely have I heard Jesus speak to me so clearly in prayer as He did that day. I did not hear Him with my ears, but His question cut through my tangled, emotion-laden thoughts with unmistakable precision. I paused and gingerly considered Jesus’ question. What struck me the most was the way He asked it. Jesus’ words weren’t huffy, as I might have said them. (“Seriously, Amanda? What do you still need that I haven’t given you already?”) Rather, He asked with longing and a desire to fulfill: Tell me what you need. I revisited my grumbling to figure out what, exactly, I needed from Him. In the end, I found nothing. I had everything I needed; just not everything I wanted. And what I especially wanted was a group of women I could get along with a little more easily.

Jesus then offered me two more words: “Trust me.” Through them, I understood that Jesus was revealing Himself to me through these women. He was loving me in ways I wasn’t used to being loved, through women whose hearts were different from my own—and yet very much the same. It was not enough for me to experience love in the way I was “used to” experiencing it. Jesus wanted my heart to resemble His own, and to do this, He needed to stretch it. Every moment of every day was a new opportunity to obey His invitation to give and receive love in new ways, beyond the tight boundaries of my own culture, upbringing, and understanding. I could dismiss the things I didn’t understand as obstacles to following God, or I could believe God was present in the very people and moments that perplexed me the most, and listen for His invitation to love Him there and receive His love in new and unexpected ways.

We often think of the will of God as something that is “out there” for us to find. But God does not hide His will from us. It is always here, taking concrete form in the situations, people, history, and circumstances that surround us. This is the context in which God urges us to “step out of the boat” of our current understanding, trust in the truth of His Word, and follow Him. When we do so, He lifts the veil on His promise to be with us always and allows us to glimpse where and how He is at work in our lives. And in the same breath, He beckons us to follow Him higher, further, and deeper still.

The Language of Love

The Daughters of St. Paul have been singing and recording albums for years, as part of our mission to proclaim Christ through media. A couple years ago, my superiors asked if I would join the choir. The request took me by surprise. I had limited talent and no experience to speak of, unless you count car karaoke. I was willing, but skeptical.

Thankfully, one of my sisters saw my plight and offered to give me some singing lessons and breathing tips. As we met in her office one afternoon, she helped me with my posture, led me through vocal warm-ups, and taught me how to project my voice from the right part of my face. I exhaled several notes at a medium volume while carefully eyeing her office window and the hallway outside.

“Sing out!” she gently encouraged.

“I’m really not a good singer,” I confessed, turning away from the window and meeting her gaze. “I don’t know why they asked me to do this.”

She nodded in understanding. “I felt the same way when they first asked me to join the choir. I’m not confident in my voice either. But if the sisters chose you, they obviously see something you don’t see.”

There it was again: the call to trust, to obey, to step out of the boat and meet Jesus in a place I had never intended to go.

My sister continued, as if she had read my thoughts. “I’ve come to realize that singing is ultimately an act of love. We can’t hear our voice the way others hear it; it resonates differently in our ears than it does for them. We sing, not because we want to know what we sound like or how good we are, but because we offer the gift of our voice to the Lord and trust that He will use it as He desires. This is our gift to Him and to His People—and if God is going to use it, we have to let go of what we think about ourselves.”

It is easy to harbor anxiety about how others see and respond to us. It is easy to make comparisons and judgments; to internalize the praise and the doubts that others voice about us; and to calculate whether the return we get is worth the effort we put into trying to communicate something to the world. It is much harder to “sing out” in love without looking for something in return. Nevertheless, this is precisely the kind of singing Christ models for us through His life of poverty, chastity, and obedience. The life of Christ is a song of selfless love and freedom, and it is taken up by those who have nothing to lose because they are secure in the knowledge that they are children of God. If we want to learn this song and hear its melody in the background of our lives, we have to practice singing it: not by our own efforts, but in communion with the Holy Spirit who has promised to teach us His language of love and attune our hearts to its everlasting cadence.

Our world needs more singers. It needs men and women who are not afraid to give God more than what they think others will understand, so that others may see in them a reflection of the God beyond all understanding. The world needs the gift of our voices and our lives, so that it might find in us—as my sisters and I have found in Christ—a language of life through which it, too, can lift the fullness of its heart to God.

Why We Love It

“Never before as a reader have I been so equally amused, inspired, and seen than I have been when reading Millennial Nuns. The Daughters of St. Paul are so full of life and joy that I dare you not to fall in love with the #MediaNuns.”

—Ronnie A., Associate Editor, on Millennial Nuns

Product Details

- Publisher: S&S/Simon Element (July 5, 2022)

- Length: 248 pages

- ISBN13: 9781982158033

Browse Related Books

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Millennial Nuns Trade Paperback 9781982158033

- Author Photo (jpg): The Daughters of Saint Paul The Daughters of Saint Paul(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit