Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

LIST PRICE $17.00

Get 30% off hardcovers with code MOM30, plus free shipping on orders of $40 or more. Terms apply.

Buy from Other Retailers

Table of Contents

About The Book

Ivy Lin is a thief and a liar—but you’d never know it by looking at her.

Raised outside of Boston, Ivy’s immigrant grandmother relies on Ivy’s mild appearance for cover as she teaches her granddaughter how to pilfer items from yard sales and second-hand shops. Thieving allows Ivy to accumulate the trappings of a suburban teen—and, most importantly, to attract the attention of Gideon Speyer, the golden boy of a wealthy political family. But when Ivy’s mother discovers her trespasses, punishment is swift and Ivy is sent to China, and her dream instantly evaporates.

Years later, Ivy has grown into a poised yet restless young woman, haunted by her conflicting feelings about her upbringing and her family. Back in Boston, when Ivy bumps into Sylvia Speyer, Gideon’s sister, a reconnection with Gideon seems not only inevitable—it feels like fate.

Slowly, Ivy sinks her claws into Gideon and the entire Speyer clan by attending fancy dinners, and weekend getaways to the cape. But just as Ivy is about to have everything she’s ever wanted, a ghost from her past resurfaces, threatening the nearly perfect life she’s worked so hard to build.

Filled with surprising twists and a nuanced exploration of class and race, White Ivy is a “highly entertaining,” (The Washington Post) “propulsive debut” (San Francisco Chronicle) that offers a glimpse into the dark side of a woman who yearns for success at any cost.

Excerpt

IVY LIN WAS A THIEF but you would never know it to look at her. Maybe that was the problem. No one ever suspected—and that made her reckless. Her features were so average and nondescript that the brain only needed a split second to develop a complete understanding of her: skinny Asian girl, quiet, overly docile around adults in uniforms. She had a way of walking, shoulders forward, chin tucked under, arms barely swinging, that rendered her invisible in the way of pigeons and janitors.

Ivy would have traded her face a thousand times over for a blue-eyed, blond-haired version like the Satterfield twins, or even a redheaded, freckly version like Liza Johnson, instead of her own Chinese one with its too-thin lips, embarrassingly high forehead, two fleshy cheeks like ripe apples before the autumn pickings. Because of those cheeks, at fourteen years old, she was often mistaken for an elementary school student—an unfortunate hindrance in everything except thieving, in which her childlike looks were a useful camouflage.

Ivy’s only source of vanity was her eyes. They were pleasingly round, symmetrically situated, cocoa brown in color, with crescent corners dipped in like the ends of a stuffed dumpling. Her grandmother had trimmed her lashes when she was a baby to “stimulate growth,” and it seemed to have worked, for now she was blessed with a flurry of thick, black lashes that other girls could only achieve with copious layers of mascara, and not even then. By any standard, she had nice eyes—but especially for a Chinese girl—and they saved her from an otherwise plain face.

So how exactly had this unassuming, big-eyed girl come to thieving? In the same way water trickles into even the tiniest cracks between boulders, her personality had formed into crooked shapes around the hard structure of her Chinese upbringing.

When Ivy was two years old, her parents immigrated to the United States and left her in the care of her maternal grandmother, Meifeng, in their hometown of Chongqing. Of her next three years in China, she remembered very little except one vivid memory of pressing her face into the scratchy fibers of her grandmother’s coat, shouting, “You tricked me! You tricked me!” after she realized Meifeng had abandoned her to the care of a neighbor to take an extra clerical shift. Even then, Ivy had none of the undiscerning friendliness of other children; her love was passionate but singular, complete devotion or none at all.

When Ivy turned five, Nan and Shen Lin had finally saved enough money to send for their daughter. “You’ll go and live in a wonderful state in America,” Meifeng told her, “called Ma-sa-zhu-sai.” She’d seen the photographs her parents mailed home, pastoral scenes of ponds, square lawns, blue skies, trees that only bloomed vibrant pink and fuchsia flowers, which her pale-cheeked mother, whom she could no longer remember, was always holding by thin branches that resembled the sticks of sugared plums Ivy ate on New Year’s. All this caused much excitement for the journey—she adored taking trips with her grandmother—but at the last minute, after handing Ivy off to a smartly dressed flight attendant with fascinating gold buttons on her vest, Meifeng disappeared into the airport crowd.

Ivy threw up on the airplane and cried nearly the entire flight. Upon landing at Logan Airport, she howled as the flight attendant pushed her toward two Asian strangers waiting at the gate with a screaming baby no larger than the daikon radishes she used to help Meifeng pull out of their soil, crusty smears all over his clenched white fists. Ivy dragged her feet, tripped over a shoelace, and landed on her knees.

“Stand up now,” said the man, offering his hand. The woman continued to rock the baby. She addressed her husband in a weary tone. “Where are her suitcases?”

Ivy wiped her face and took the man’s hand. She had already intuited that tears would have no place with these brick-faced people, so different from the gregarious aunties in China who’d coax her with a fresh box of chalk or White Rabbit taffies should she display the slightest sign of displeasure.

This became Ivy’s earliest memory of her family: Shen Lin’s hard, calloused fingers over her own, his particular scent of tobacco and minty toothpaste; the clear winter light flitting in through the floor-to-ceiling windows beyond which airplanes were taking off and landing; her brother, Austin, no more than a little sack in smelly diapers in Nan’s arms. Walking among them but not one of them, Ivy felt a queer, dissociative sensation, not unlike being submerged in a bathtub, where everything felt both expansive and compressed. In years to come, whenever she felt like crying, she would invoke this feeling of being submerged, and the tears would dissipate across her eyes in a thin glistening film, disappearing into the bathwater.

NAN AND SHEN’S child-rearing discipline was heavy on the corporal punishment but light on the chores. This meant that while Ivy never had to make a bed, she did develop a high tolerance for pain. As with many immigrant parents, the only real wish Nan and Shen had for their daughter was that she become a doctor. All Ivy had to do was claim “I want to be a doctor!” to see her parents’ faces light up with approval, which was akin to love, and just as scarce to come by.

Meifeng had been an affectionate if brusque caretaker, but Nan was not this way. The only times Ivy felt the warmth of her mother’s arms were when company came over. Usually, it was Nan’s younger sister, Ping, and her husband, or one of Shen’s Chinese coworkers at the small IT company he worked for. During those festive Saturday afternoons, munching on sunflower seeds and lychees, Nan’s downturned mouth would right itself like a sail catching wind, and she would transform into a kinder, more relaxed mother, one without the little pinch between her brows. Ivy would wait all afternoon for this moment to scoot close to her mother on the sofa… closer… closer… and then, with the barest of movements, she’d slide into Nan’s lap.

Sometimes, Nan would put her hands around Ivy’s waist. Other times, she’d pet her head in an absent, fitful way, as if she wasn’t aware of doing it. Ivy would try to stay as still as possible. It was a frightful, stolen pleasure, but how she craved the touch of a bosom, a fleshy lap to rest on. She’d always thought she was being exceedingly clever, that her mother hadn’t a clue what was going on. But when she was six years old, she did the same maneuver, only this time, Nan’s body stiffened. “Aren’t you a little old for this now?”

Ivy froze. The adults around her chuckled. “Look how ni-ah your daughter is,” they exclaimed. Ni-ah was Sichuan dialect for clingy. Ivy forced her eyes open as wide as they would go. It was no use. She could taste the salt on her lips.

“Look at you,” Nan chastised. “They’re just teasing! I can’t believe how thin-skinned you are. You’re an older sister now, you should be braver. Now be good and ting hua. Go wipe your nose.”

To her dying day, Ivy would remember this feeling: shame, confusion, hurt, defiance, and a terrible loneliness that turned her permanently inward, so that when Meifeng later told her she had been a trusting and affectionate baby, she thought her grandmother was confusing her with Austin.

IVY BECAME A secretive child, sharing her inner life with no one, except on occasion, Austin, whose approval, unlike everyone else’s in the family, came unconditionally. Suffice it to say, neither of Ivy’s parents provided any resources for her fanciful imagination—what kind of life would she have, what kind of love and excitement awaited her in her future? These finer details Ivy filled in with books.

She learned English easily—indeed, she could not remember a time she had not understood English—and became a precocious reader. The tiny, unkempt West Maplebury Library, staffed by a half-deaf librarian, was Nan’s version of free babysitting. It was Ivy’s favorite place in the whole world. She was drawn to books with bleak circumstances: orphans, star-crossed lovers, captives of lecherous uncles and evil stepmothers, the anorexic cheerleader, the lonely misfit. In every story, she saw herself. All these heroines had one thing in common, which was that they were beautiful. It seemed to Ivy that outward beauty was the fountain from which all other desirable traits sprung: intelligence, courage, willpower, purity of heart.

She cruised through elementary school, neither at the top of her class nor the bottom, neither popular nor unpopular, but it wasn’t until she transferred to Grove Preparatory Day School in sixth grade—her father was hired as the computer technician there, which meant her tuition was free—that she found the central object of her aspirational life: a certain type of clean-cut, all-American boy, hitherto unknown to her; the type of boy who attended Sunday school and plucked daisies for his mother on Mother’s Day. His name was Gideon Speyer.

Ivy soon grasped the colossal miracle it would take for a boy like Gideon to notice her. He was friendly toward her, they’d even exchanged phone numbers once, for a project in American Lit, but the other Grove girls who swarmed around Gideon wore brown penny loafers with white cotton knee socks while Ivy was clothed in old-fashioned black stockings and Nan’s clunky rubber-soled lace-ups. She tried to emulate her classmates’ dress and behaviors as best she could with her limited resources: she pulled her hair back with a headband sewn from an old silk scarf, tossed green pennies onto the ivy-covered statue of St. Mark in the courtyard, ate her low-fat yogurt and Skittles under the poplar trees in the springtime—still she could not fit in.

How could she ever get what she wanted from life when she was shy, poor, and homely?

Her parents’ mantra: The harder you work, the luckier you are.

Her teachers’ mantra: Treat others the way you want to be treated.

The only person who taught her any practical skills was Meifeng. Ivy’s beloved grandmother finally received her US green card when Ivy turned seven. Two years of childhood is a decade of adulthood. Ivy still loved Meifeng, but the love had become the abstract kind, born of nostalgic memories, tear-soaked pillows, and yearning. Ivy found this flesh-and-blood Meifeng intimidating, brisk, and loud, too loud. Having forgotten much of her Chinese vocabulary, Ivy was slow and fumbling when answering her grandmother’s incessant questions; when she wasn’t at the library, she was curled up on the couch like a snail, reading cross-eyed.

Meifeng saw that she had no time to lose. She felt it her duty to instill in her granddaughter the two qualities necessary for survival: self-reliance and opportunism.

Back in China, this had meant fixing the books at her job as a clerk for a well-to-do merchant who sold leather gloves and shoes. The merchant swindled his customers by upcharging every item, even the fake leather products; his customers made up the difference with counterfeit money and sleight of hand. Even the merchant’s wife pilfered money from his cash register to give to her own parents and siblings. And it was Meifeng who jotted down all these numbers, adding four-digit figures in her head as quick as any calculator, a penny or two going into her own paycheck with each transaction.

Once in Massachusetts, unable to find work yet stewing with enterprising restlessness, Meifeng applied the same skills she had previously used as a clerk toward saving money. She began shoplifting, price swapping, and requesting discounts on items for self-inflicted defects. She would hide multiple items in a single package and only pay for one.

The first time Meifeng recruited Ivy for one of these tasks was at the local Goodwill, the cheapest discount store in town. Ivy had been combing through a wooden chest of costume jewelry and flower brooches when her grandmother called her over using her pet name, Baobao, and handed her a wool sweater that smelled of mothballs. “Help me get this sticker off,” said Meifeng. “Don’t rip it now.” She gave Ivy a look that said, You’d better do it properly or else.

Ivy stuck her nail under the corner of the white $2.99 sticker. She pushed the label up with minuscule movements until she had enough of an edge to grab between her thumb and index finger. Then, ever so slowly, she peeled off the sticker, careful not to leave any leftover gunk on the label. After Ivy handed the sticker over, Meifeng stuck it on an ugly yellow T-shirt. Ivy repeated the same process for the $0.25 sticker on the T-shirt label. She placed this new sticker onto the price tag for the sweater, smoothing the corners down flat and clean.

Meifeng was pleased. Ivy knew because her grandmother’s face was pulled back in a half grimace, the only smile she ever wore. “I’ll buy you a donut on the way home,” said Meifeng.

Ivy whooped and began spinning in circles in celebration. In her excitement, she knocked over a stand of scarves. Quick as lightning, Meifeng grabbed one of the scarves and stuffed it up her left sleeve. “Hide one in your jacket—any one. Quickly!”

Ivy snatched up a rose-patterned scarf (the same one she would cut up and sew into a headband years later) and bunched it into a ball inside her pocket. “Is this for me?”

“Keep it out of sight,” said Meifeng, towing Ivy by the arm toward the register, a shiny quarter ready, to pay for the woolen sweater. “Let this be your first lesson: give with one hand and take with the other. No one will be watching both.”

THE GOODWILL CLOSED down a year later, but by then, Meifeng had discovered something even better than Goodwill—an event Americans called a yard sale, which Meifeng came to recognize by the hand-painted cardboard signs attached to the neighborhood trees. Each weekend, Meifeng scoured the sidewalks for these hand-painted signs, dragging her grandchildren to white-picket-fenced homes with American flags fluttering from the windows and lawns lined with crabapple trees. Meifeng bargained in broken English, holding up arthritic fingers to display numbers, all the while loudly protesting “Cheaper, cheaper,” until the owners, too discomfited to argue, nodded their agreement. Then she’d reach into her pants and pull out coins and crumpled bills from a cloth pouch, attached by a cord to her underwear.

Other yard sale items, more valuable than the rest, Meifeng simply handed to Ivy to hide in her pink nylon backpack. Silverware. Belts. A Timex watch that still ticked. No one paid any attention to the children running around the yard, and if after they left the owner discovered that one or two items had gone unaccounted for, he simply attributed it to his worsening memory.

Walking home by the creek after one of these excursions, Meifeng informed Ivy that Americans were all stupid. “They’re too lazy to even keep track of their own belongings. They don’t ai shi their things. Nothing is valuable to them.” She placed a hand on Ivy’s head. “Remember this, Baobao: when winds of change blow, some build walls. Others build windmills.”

Ivy repeated the phrase. I’m a windmill, she thought, picturing herself swinging through open skies, a balmy breeze over her gleaming mechanical arms.

Austin nosed his way between the two women. “Can I have some candy?”

“What’d you do with that lollipop your sister gave you?” Meifeng barked. “Dropped it again?”

And Austin, remembering his loss, scrunched up his face and cried.

IVY KNEW HER brother hated these weekends with their grandmother. At five years old, Austin had none of the astute restraint his sister had had at his age. He would howl at the top of his lungs and bang his chubby fists on the ground until Meifeng placated him with promises to buy a toy—“a dollar toy?”—or a trip to McDonald’s, something typically reserved for special occasions. Meifeng would never have tolerated such a display from Ivy, but everyone in the Lin household indulged Austin, the younger child, and a boy at that. Ivy wished she had been born a boy. Never did she wish this more fervently than at twelve years old, the morning she awoke to find her underwear streaked with a matte, rust-like color. Womanhood was every bit as inconvenient as she’d feared. Nan did not own makeup or skincare products. She cut her own hair and washed her face every morning with water and a plain washcloth. One week a month, she wore a cloth pad—reinforced with paper towels on the days her flow was heaviest—which she rinsed each night in the sink and hung out to dry on the balcony. But American women had different needs: disposable pads, tampons, bras, razors, tweezers. It was unthinkable for Ivy to ask for these things. The idea of removing one’s leg or underarm hair for aesthetic reasons would have instilled in her mother a horror akin to slicing one’s skin open. In this respect, Nan and Meifeng were of one mind. Ivy knew she could only rely on herself to obtain these items. That was when she graduated from yard sales to the two big-box stores in town: Kmart and T.J.Maxx.

Her first conquests: tampons, lip gloss, a box of Valentine’s Day cards, a bag of disposable razors. Later, when she became bolder: rubber sandals, a sports bra, mascara, an aquamarine mood ring, and her most prized theft yet—a leather-bound diary with a gold clasp lock. These contrabands she hid in the nooks and crannies of her dresser, away from puritan eyes. At night, Ivy would sneak out her diary and copy beautiful phrases from her novels—For things seen pass away, but the things that are unseen are eternal—and throughout those last two years of middle school, she wrote love letters to Gideon Speyer: I had a vivid dream this morning, it was so passionate I woke up with an ache… I held your face in my hands and trembled… if only I wasn’t so scared of getting close to you… if only you weren’t so perfect in every way…

And so Ivy grew like a wayward branch. Planted to the same root as her family but reaching for something beyond their grasp. Years of reconciling her grandmother’s teachings with her American values had somehow culminated in a confused but firm belief that in order to become the “good,” ting hua girl everyone asked of her, she had to use “smart” methods. But she never admitted how much she enjoyed these methods. She never got too greedy. She never got sloppy. And most important, she never got caught. It comforted her to think that even if she were accused of wrongdoing someday, it would be her accuser’s word against hers—and if there was anything she prided herself on other than being a thief, it was being a first-rate liar.

Reading Group Guide

Get a FREE ebook by joining our mailing list today! Plus, receive recommendations for your next Book Club read.

Introduction

Ivy Lin is a thief and a liar—but you’d never know it by looking at her.

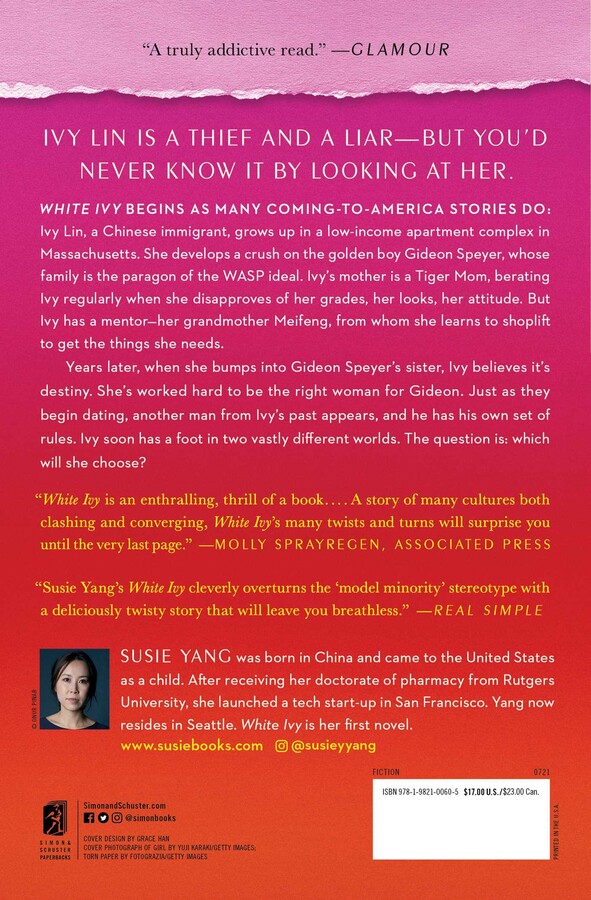

White Ivy begins as many coming-to-America stories do: Ivy Lin, a Chinese immigrant, grows up in a low-income apartment complex in Massachusetts desperate to assimilate with her American peers. She develops a crush on the golden boy Gideon Speyer, whose patrician New England family is the paragon of the WASP ideal. Ivy’s mother is a Tiger Mom, berating Ivy regularly when she disapproves of her grades, her looks, her attitude. But that’s where the familiar story ends. Because Ivy has a mentor—her grandmother Meifeng—from whom she learns to shoplift to get the things she needs.

Ivy develops a taste for winning and for wealth. Years later, when she bumps into Gideon’s sister, Ivy believes it’s destiny. She’s worked long and hard to be the right woman for Gideon. But just as they begin dating, another man from Ivy’s past appears, and he has his own set of rules. Ivy soon has a foot in two vastly different worlds.

The question is: Which will she choose? A coming of age story, a love triangle, an exploration of class and race and identity, White Ivy is a page-turner that will appeal to fans of The Talented Mr. Ripley. Ivy Lin is compelling and unnerving. And you’ll root for her—perhaps in spite of yourself.

Topics & Questions for Discussion

1. After finishing the novel, reexamine the title. What do you think it refers to? In what ways can the title be interpreted?

2. The novel is both a thriller with plot twists and social commentary on the “model minority” myth. How does Susie Yang meld these usually disparate genres?

3. Since middle school, Ivy values appearances and decorum. She believes that “Muddy water, let stand, becomes clear” (p. 39). She wants others to think that she is morally upright, and she is ashamed when Roux catches her stealing. Why do you think Ivy values the appearance of propriety? How much of it is from her family and how much of it is from her environment?

4. Meifeng shares with Ivy the story about how her parents got together. Years later, Ivy learns new details of that story from her own mother. How does Ivy’s evolving understanding of her parents’ history inform how she pursues her goals?

5. Ivy meets Dave, Gideon’s mentor, and his wife, Liana, an Asian woman, at a party. How does their interracial relationship differ from that of Ivy and Gideon?

6. Ivy thinks at one point, “Perhaps this was the secret to a lasting marriage: to always uphold a veil of mystery between each other” (p. 147). Does this veil exist in her relationship with Gideon? Does it exist in her relationship with Roux? Why or why not?

7. Ivy’s and Gideon’s families meet for the first time on Thanksgiving. How do their families’ cultures clash? How do their cultural differences manifest in the discussion about the wedding?

8. Throughout Ivy’s childhood, her parents are strict and frugal. Later on, her parents attain middle-class legitimacy and are more supportive of her. How does Ivy’s relationship to her parents develop over the course of the book?

9. Ivy is ambitious and covets privilege. She longs for money, access, and legitimacy. What different desires do Gideon and Roux satisfy in Ivy? In what ways do their respective relationships remain unsatisfactory for her?

10. In a violent altercation, Ivy and Roux hit each other. Afterward, Roux says “I love you” for the first time. How do Roux’s childhood and past relationships influence his behavior toward Ivy?

11. Ivy dyes her hair blond before making a crucial decision in the book. What does her blond hair signify?

12. What do White Anglo-Saxon Protestants (WASPs) exemplify for Ivy? What attraction do they hold and how does Gideon exemplify this ideal?

13. Why does Ivy struggle to embrace her Chinese culture?

14. On her wedding day, Ivy learns not only a truth about Gideon, but also about Sylvia’s role in their relationship. How does Sylvia protect her brother?

15. In your opinion, does Ivy succeed in the end? Is she happy?

Enhance Your Book Club

1. With its dark twists and turns and addictive plot, White Ivy seems like the perfect book to adapt into a movie or TV show. Who would you cast as its stars?

2. Ivy straddles both Chinese and WASP culture. As a group, discuss how you may have had to navigate and embrace different cultures.

3. Ivy is a strong-willed heroine who is shameless about her desires; she ruthlessly pursues her ambitions. Name other heroines in literature who remind you of Ivy.

A Conversation with Susie Yang

Q: White Ivy has one of the most memorable lines in contemporary fiction: “Ivy Lin was a thief but you would never know it to look at her.” How did this line come to you?

A: I knew I wanted to create a protagonist whose outer appearance was incongruous with her personality so she would be underestimated and misjudged upon initial impression. When I had the idea of Ivy shoplifting as a teenager to acquire the things her parents wouldn’t buy her, the first line came to me.

Q: Ivy Lin subverts the “model minority” stereotype in countless ways, especially as an anti-heroine who dismantles its tropes. What is your relationship to her character? What emotions did you hope she would evoke in readers?

A: I both pity and admire Ivy. I think her admirable qualities include determination, adaptability, and resilience. She is a person who has a hunger for life in a way that I envy! But I also pity her because the very things she wants so badly in life—to be a part of a very white, very exclusive patrician world—are in fact self-delusions and ultimately things that will make her miserable. This is the tragedy of Ivy’s character, and I hope readers will both understand her motivations and also see how her assumptions are misplaced and lead her to make sacrifices on a scale that is quite frightening. By the end of the book, I think Ivy also realizes her dreams are, in fact, illusions, but she is determined to uphold the illusion to the very end, no matter the cost. I hope readers will feel scared by this!

Q: Roux and Gideon are both intriguing characters who embody different desires for Ivy. What was the inspiration for their stories and how did the characters change during the course of writing of this novel?

A: The inspiration for Roux came from my best friend in the third grade, who lived next door to me in our development in Baltimore. Their family was Romanian and she had an older brother who was very mysterious and rode a motorcycle around town. I’ve never spoken to her brother, yet for some reason, when I wrote about Ivy’s childhood friend, I pictured this brother. Gideon is really more of a type than based on a real person. He is a reserved man who is more interested in work than romance, and has difficulty in communicating his vulnerabilities. I think a lot of repressed kids end up like this. I actually had a hard time writing Gideon because I had to make him feel alluring and indiscernible to Ivy but not to the reader, who would easily see through his courteous manners into his more selfish intentions. Neither Roux nor Gideon changed much throughout the course of writing the novel because they were always foils for each other, and choices Ivy has to grapple with as she comes to terms with what’s important to her.

Q: At the end of the novel, Ivy finally realizes that “the thing that no one could take away from you—it was family” (p. 351). Can you tell us about your relationship with your family?

A: My family definitely formed me into the person I am today. Looking back, I don’t think my parents ever treated me like a child. They took all my opinions seriously and they would frequently share with me their own burdens and struggles, which was their way of teaching me about the world and how to navigate it. My dad and I would take long drives and talk about everything—What is happiness? What is success? What lies do we tell ourselves and why?—and it was through these talks that I began to formulate and express my own worldviews very early on in life. My mom was a more traditional stay-at-home mom, but she would always tell me how smart and capable I was. It was my parents’ absolute belief in me that formed the bedrock of my self-confidence. I also have a younger brother who is my very best friend now, but when we were children, I think I operated more as a third parent. I was very bossy! So many of my current values come from my family.

Q: Which authors do you admire?

A: I admire so many authors! The ones I keep coming back to are Simone de Beauvoir, John Steinbeck, Betty Smith, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Yukio Mishima, Virginia Woolf, and Marguerite Duras. In terms of contemporary authors, I love Haruki Murakami, Rachel Kushner, Min Jin Lee, Sally Rooney, Kazuo Ishiguro, Elena Ferrante, Edward St Aubyn, and Rohinton Mistry.

Q: This novel deals with pressures Ivy experiences assimilating to America as an immigrant. How much of Ivy’s experiences were informed by your own?

A: I don’t think Ivy’s experiences overlap that much with my own. I tend to draw inspiration from everything I observe, which can be as random as an encounter with a stranger, or a story my friend tells me, or even a snippet I read in the news. All these little details fuse in my imagination and become my characters’ backgrounds. The main part of Ivy’s life that is inspired by my own is her feeling of otherness. I’ve moved around a lot my entire life and before college I went to eight different schools, so I was used to my identity as the perpetual “new girl.” The other section that is loosely based on my experiences is when Ivy first returns to China as a teenager. I’ve visited China many times growing up and I loved every trip. Part of my motivation in writing that section of the book was out of nostalgia and a tribute to the summer vacations of my youth.

Q: Ivy is fascinated by White Anglo-Saxon Protestants and frequently contrasts them with her own Chinese background. Why did you choose to focus on both cultures?

A: I wanted to write about Ivy’s Chinese heritage because it’s my heritage, but I didn’t want the book to be solely focused on her immigrant experience. It was important to me that this story was foremost going to be a fun, twisty tale about a social climber who orchestrates her own demise. Also, I really dislike all forms of research, so Ivy’s Chinese culture was the one I could most easily invoke. In terms of the WASP world, I chose it mainly because it was unfamiliar to Ivy and a natural emblem of her unrealistic ambitions. Actually, Ivy doesn’t really belong in either culture. She wants to discard her Chinese heritage but she also doesn’t understand the world that she’s discarding it for. So it’s interesting to see how she picks and chooses the customs and values from each culture that suit her current needs, the mark of a true chameleon.

Q: Throughout the novel, Ivy strives to attain privilege. What do you think privilege means to Ivy?

A: Privilege and identity go hand-in-hand for Ivy. She doesn’t see privilege as a relative scale but as an objective trait—you are privileged or you’re not. So much of Ivy’s yearning is to be what she considers a privileged person, which on the surface can mean money, nice clothes, elite clubs; but actually, what Ivy really wants is self-assurance, which she believes privileged people naturally have.

Q: Why did you choose to title your novel White Ivy?

A: I was looking through hundreds of Chinese proverbs for the inscription page of the book and came upon the one that said: the snow goose needs not bathe to make itself white. It speaks to the idea of intrinsic versus obtained value. Why is the former considered more noble than the latter? Ivy idolizes intrinsic traits—like beauty or family background—yet she works hard to shed her own intrinsic merits in favor of exterior ones. So White Ivy speaks to her journey in masquerading herself as the “real thing.” And of course, there is the double meaning with race.

Q: Can you tell us what you’re working on now?

A: I am working on a story about the dichotomy between our public personas and our private selves, and how the two can both clash and complement each other, as told through a relationship between two high school sweethearts that spans ten years.

Product Details

- Publisher: S&S/Marysue Rucci Books (July 27, 2021)

- Length: 368 pages

- ISBN13: 9781982100605

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

Named one of the Best Books of 2020 by USA Today (4 Stars) | one of the Most Anticipated Books by Entertainment Weekly, O Magazine, Time Magazine, Glamour, Vogue, The Washington Post, Buzzfeed, ABC News, Bustle, Lit Hub, Newsday, The Millions, Town & Country, Refinery 29, Shondaland, Crime Reads

Longlisted for the Center for Fiction's First Novel Prize

"A twisty, unputdownable psychological thriller. Clear your schedule." — People, Book of the Week

"A truly addictive read." — Glamour

"There's nothing better than a novel with an unpredictable plot. And White Ivy, Susie Yang's debut novel... is exactly that." — USA Today (4 out of 4 stars)

“White Ivy is an enthralling, thrill of a book. It is fascinating to spend time inside Ivy’s mind, unique and unapologetic in its bold (and often bad) decisions. A story of many cultures both clashing and converging, White Ivy’s many twists and turns will surprise you until the very last page." — Molly Sprayregen, Associated Press

"Susie Yang delves into class warfare and deceit in the season's biggest debut" — Entertainment Weekly

"The genius of White Ivy is that each plot point of the romance is fulfilled but also undercut by a traumatic pratfall, described in language as bright and scarring as a wound." — The Los Angeles Times

"The modern story of clashing cultures and classes already reads like Crazy Rich Asians meets Donna Tartt’s A Secret History meets Paul’s Case, Willa Cather’s classic story of a desperate middle-class climb. But White Ivy, the propulsive debut novel by Susie Yang, is more than plot twists and love triangles. It’s also an astute chronicle of cultures, gender dynamics and the complicated business of self-creation in America." — San Francisco Chronicle

"Susie Yang’s White Ivy cleverly overturns the 'model minority' stereotype with a deliciously twisty story that will leave you breathless." — Real Simple

"A highly entertaining, well-plotted character study about a young woman whose obsession with the shallow signifiers of success gets her in too deep." — The Washington Post

"Yang excels at drawing sharp characters, making excruciating observations about class, family, and social norms, and painting the losses of migration and struggles Asians and other immigrants face in America. An easy page-turner... the cutting prose movingly portrays many layers of tribulation and traumas, and marks Yang as a voice to watch." — Boston Globe

"Susie Yang's White Ivy Is The Talented Mr. Ripley for the Instagram Age" — Bustle

“White Ivy has it all — it’s a coming of age story, a love triangle rich in complications of race and class, and though it offers the pleasures of a literary novel such as complex characters and interesting writing, it also has the attractions of a psychological thriller: jaw-dropping plot twists and an unpredictable ending... [This is a ] sharply observed and boldly imagined novel." — Star Tribune

"Yang’s dark, spellbinding debut gives insight into the immigrant experience and life in the upper class, challenging the stereotypes and perceptions associated with both. The surprising twists, elegant prose, and complex characters in this coming-of-age story make this a captivating read." — Booklist (starred review)

"What begins as a story of a young woman’s struggles to assimilate quickly becomes a much darker tale of love, lies, and obsession, in which there are no boundaries to finding the fulfillment of one’s own dreams. Yang’s skill in creating surprising, even shocking plot twists will leave readers breathless." — Library Journal (starred review)

"In Ivy, Yang has created an ambitious and sharp yet believably flawed heroine who will win over any reader, and the accomplished plot is layered and full of revelations. This is a beguiling and shattering coming-of-age story." — Publishers Weekly

"The intelligent, yearning, broken, and deeply insecure Ivy will enthrall readers, and Yang’s beautifully written novel ably mines the complexities of class and privilege. A sophisticated and darkly glittering gem of a debut." — Kirkus Reviews

"Electrifying... Part immigrant story, part elitist takedown, part contemporary novel of wicked manners, White Ivy is an unpredictable spectacle... Ivy Lin proves to be the antihero readers will love to hate in debut novelist Susie Yang's assured, deft, biting novel of (manipulative) manners." — Shelf Awareness (starred review)

"Yang takes a character who is a confessed thief from the first page, and etches her with qualities that turn her into a complex, layered, and unpredictable character."— Chicago Review of Books

"It's a testament to Susie Yang's skill that she can explore and upend our ideas of class, race, family, and identity while moving us through a plot that twists in such wonderful ways. But none of that would matter nearly as much if not for the truly unforgettable narrator, Ivy, who is so hypnotic, the way her voice feels both wild and controlled. She ran right through me." — Kevin Wilson, New York Times bestelling author of Nothing to See Here

“White Ivy is dark and delicious. Ivy Lin eviscerates the model minority stereotype with a smile on her lips and a boot on your neck. Cancel your weekend plans, because you won’t be able to take your eyes off Ivy Lin.” — Lucy Tan, author of What We Were Promised

“White Ivy is magic and a necessary corrective both to the stereotypes and the pieties that too easily characterize the immigrant experience. Most pleasing of all is the story of Ivy Lin, a daring young woman in search of herself, and not soon to be forgotten.” — Joshua Ferris, prize-winning author of To Rise Again at a Decent Hour

"Elegant and terrifying, steely and sparkling, White Ivy is a propulsive story told with the satisfying simplicity of a classic." — Rebecca Dinerstein Knight, author of Hex

"Bold, daring, and sexy, White Ivy is the immigrant story we’ve been dying to hear. Rather than submit to love, Ivy seeks it out, sinks her teeth into it, and doesn’t let go. A stunning debut." — Neel Patel, author of If You See Me, Don't Say Hi

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): White Ivy Trade Paperback 9781982100605

- Author Photo (jpg): Susie Yang Photograph © Onur Pinar Photography(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit