Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

The Good Life

Lessons from the World's Longest Scientific Study of Happiness

LIST PRICE $19.99

Get 30% off hardcovers with code MOM30, plus free shipping on orders of $40 or more. Terms apply.

Buy from Other Retailers

Table of Contents

About The Book

What makes for a happy life, a fulfilling life? A good life? In their “captivating” (The Wall Street Journal) book, the directors of the Harvard Study of Adult Development, the longest scientific study of happiness ever conducted, show that the answer to these questions may be closer than you realize.

What makes a life fulfilling and meaningful? The simple but surprising answer is: relationships. The stronger our relationships, the more likely we are to live happy, satisfying, and healthier lives. In fact, the Harvard Study of Adult Development reveals that the strength of our connections with others can predict the health of both our bodies and our brains as we go through life.

The invaluable insights in this book emerge from the revealing personal stories of hundreds of participants in the Harvard Study as they were followed year after year for their entire adult lives, and this wisdom was bolstered by research findings from many other studies. Relationships in all their forms—friendships, romantic partnerships, families, coworkers, tennis partners, book club members, Bible study groups—all contribute to a happier, healthier life. And as The Good Life shows us, it’s never too late to strengthen the relationships you already have, and never too late to build new ones. The Good Life provides examples of how to do this.

Dr. Waldinger’s TED Talk about the Harvard Study, “What Makes a Good Life,” has been viewed more than 42 million times and is one of the ten most-watched TED talks ever. The Good Life has been praised by bestselling authors Jay Shetty (“an empowering quest towards our greatest need: meaningful human connection”), Angela Duckworth (“In a crowded field of life advice...Schulz and Waldinger stand apart”), and happiness expert Laurie Santos (“Waldinger and Schulz are world experts on the counterintuitive things that make life meaningful”).

With “insightful [and] interesting” (Daniel Gilbert, New York Times bestselling author of Stumbling on Happiness) life stories, The Good Life shows us how we can make our lives happier and more meaningful through our connections to others.

Excerpt

There isn’t time, so brief is life, for bickerings, apologies, heartburnings, callings to account. There is only time for loving, and but an instant, so to speak, for that.

Mark Twain

Let’s begin with a question:

If you had to make one life choice, right now, to set yourself on the path to future health and happiness, what would it be?

Would you choose to put more money into savings each month? To change careers? Would you decide to travel more? What single choice could best ensure that when you reach your final days and look back, you’ll feel that you’ve lived a good life?

In a 2007 survey, millennials were asked about their most important life goals. Seventy-six percent said that becoming rich was their number one goal. Fifty percent said a major goal was to become famous. More than a decade later, after millennials had spent more time as adults, similar questions were asked again in a pair of surveys. Fame was now lower on the list, but the top goals again included things like making money, having a successful career, and becoming debt-free.

These are common and practical goals that extend across generations and borders. In many countries, from the time they are barely old enough to speak, children are asked what they want to be when they grow up—that is, what careers they intend to pursue. When adults meet new people, one of the first questions asked is, “What do you do?” Success in life is often measured by title, salary, and recognition of achievement, even though most of us understand that these things do not necessarily make for a happy life on their own. Those who manage to check off some or even all of the desired boxes often find themselves on the other side feeling much the same as before.

Meanwhile, all day long we’re bombarded with messages about what will make us happy, about what we should want in our lives, about who is doing life “right.” Ads tell us that eating this brand of yogurt will make us healthy, buying that smartphone will bring new joy to our lives, and using a special face cream will keep us young forever.

Other messages are less explicit, woven into the fabric of daily living. If a friend buys a new car, we might wonder if a newer car would make our own life better. As we scroll social media feeds seeing only pictures of fantastic parties and sandy beaches, we might wonder if our own life is lacking in parties, lacking in beaches. In our casual friendships, at work, and especially on social media, we tend to show each other idealized versions of ourselves. We present our game faces, and the comparison between what we see of each other and how we feel about ourselves leaves us with the sense that we’re missing out. As an old saying goes, We are always comparing our insides to other people’s outsides.

Over time we develop the subtle but hard-to-shake feeling that our life is here, now, and the things we need for a good life are over there, or in the future. Always just out of reach.

Looking at life through this lens, it’s easy to believe that the good life doesn’t really exist, or else that it’s only possible for others. Our own life, after all, rarely matches the picture we’ve created in our heads of what a good life should look like. Our own life is always too messy, too complicated to be good.

Spoiler alert: The good life is a complicated life. For everybody.

The good life is joyful… and challenging. Full of love, but also pain. And it never strictly happens; instead, the good life unfolds, through time. It is a process. It includes turmoil, calm, lightness, burdens, struggles, achievements, setbacks, leaps forward, and terrible falls. And of course, the good life always ends in death.

A cheery sales pitch, we know.

But let’s not mince words. Life, even when it’s good, is not easy. There is simply no way to make life perfect, and if there were, then it wouldn’t be good.

Why? Because a rich life—a good life—is forged from precisely the things that make it hard.

This book is built on a bedrock of scientific research. At its heart is the Harvard Study of Adult Development, an extraordinary scientific endeavor that began in 1938, and against all odds is still going strong today. Bob is the fourth director of the Study, and Marc its associate director. Radical for its time, the Study set out to understand human health by investigating not what made people sick, but what made them thrive. It has recorded the experience of its participants’ lives more or less as they were happening, from childhood troubles, to first loves, to final days. Like the lives of its participants, the Harvard Study’s road has itself been long and winding, evolving in its methods over the decades and expanding to now include three generations and more than 1,300 of the descendants of its original 724 participants. It continues to evolve and expand today, and is the longest in-depth longitudinal study of human life ever done.

But no single study, no matter how rich, is enough to permit broad claims about human life. So while this book stands directly on the foundation of the Harvard Study, it is supported on all sides by hundreds of other scientific studies involving many thousands of people from all over the world. The book is also threaded with wisdom from the recent and ancient past—enduring ideas that mirror and enrich modern scientific understandings of the human experience. It is a book primarily about the power of relationships, and it is deeply informed, appropriately, by the long and fruitful friendship of its authors.

But the book would not exist without the human beings who took part in the Harvard Study’s research—whose honesty and generosity made this unlikely study possible in the first place.

People like Rosa and Henry Keane.

“What is your greatest fear?”

Rosa read the question out loud and then looked across the kitchen table at her husband, Henry. Now in their 70s, Rosa and Henry had lived in this house and sat at this same table together on most mornings for more than fifty years. Between them sat a pot of tea, an open pack of Oreos (half eaten), and an audio recorder. In the corner of the room, a video camera. Next to the video camera sat a young Harvard researcher named Charlotte, quietly observing and taking notes.

“It’s quite the question,” Rosa said.

“My greatest fear?” Henry said to Charlotte. “Or our greatest fear?”

Rosa and Henry didn’t think of themselves as particularly interesting subjects for a study. They’d both grown up poor, married in their 20s, and raised five kids together. They’d lived through the Great Depression and plenty of hard times, sure, but that was no different from anyone else they knew. So they never understood why Harvard researchers were interested in the first place, let alone why they were still interested, still calling, still sending questionnaires, and occasionally still flying across the country to visit.

Henry was only 14 years old and living in Boston’s West End, in a tenement with no running water, when researchers from the Study first knocked on his family’s door and asked his perplexed parents if they could make a record of his life. The Study was in full swing when he married Rosa in August of 1954—the records show that when she said yes to his proposal, Henry couldn’t believe his luck—and now here they were in October of 2004, two months after their fiftieth wedding anniversary. Rosa had been asked to participate more directly in the Study in 2002. It’s about time, she said. Harvard had been tracking Henry year after year since 1941. Rosa often said she thought it was odd that he still agreed to be involved as an older man, because he was so private otherwise. But Henry said he felt a sense of duty to participate and had also developed an appreciation for the process because it gave him perspective on things. So, for sixty-three years he had opened his life to the research team. In fact, he’d told them so much about himself, and for so long, that he couldn’t even remember what they did and didn’t know. But he assumed they knew everything, including certain things he’d never told anyone but Rosa, because whenever they asked a question he did his best to tell them the truth.

And they asked a lot of questions.

“Mr. Keane was clearly flattered that I had come to Grand Rapids to interview them,” Charlotte would write in her field notes, “and this set a friendly atmosphere for the interview. I found him to be a cooperative and interested person. He was thoughtful about each answer, and often paused for a few moments before he responded. He was friendly though, and I felt that he was like the stereotype of the quiet man from Michigan.”

Charlotte was there for a two-day visit to interview the Keanes and administer a survey—a very long survey—of questions about their health, their individual lives, and their life together. Like most of our young researchers embarking on new careers, Charlotte had her own questions about what makes a good life and about how her current choices might affect her future. Was it possible that insights about her own life could be locked away in the lives of others? The only way to find out was to ask questions, and to be deeply attentive to every person she interviewed. What was important to this particular individual? What gave their days meaning? What had they learned from their experiences? What did they regret? Every interview presented Charlotte with new opportunities to connect with a person whose life was further along than her own, and who came from different circumstances and a different moment in history.

Today she would interview Henry and Rosa together, administer the survey, and then videotape them talking together about their greatest fears. She would also interview them separately in what we call “attachment interviews.” Back in Boston the videotapes and interview transcripts would be studied so that the way Henry and Rosa talked about each other, their nonverbal cues, and many other bits of information could be coded into data on the nature of their bond—data that would become part of their files and one small but important piece of a giant dataset on what a lived life is actually like.

What is your greatest fear? Charlotte had already recorded their individual answers to this question in separate interviews, but now it was time to discuss the question with each other.

The discussion went like this:

“I like the hard questions in a certain way,” Rosa said.

“Well good,” Henry said. “You go first.”

Rosa was quiet for a moment and then told Henry her greatest fear was that he might develop a serious health condition, or that she would have another stroke. Henry agreed that those were scary possibilities. But, he said, they were getting to a point now where something like that was probably inevitable. They spoke at length about how a serious illness might affect their adult children’s lives, and each other. Eventually Rosa admitted that there was only so much a person could anticipate, and there was no use in getting upset before it happened.

“Is there another question?” Henry asked Charlotte.

“What’s your greatest fear, Hank?” Rosa said.

“I was hoping you would forget to ask me,” Henry said, and they laughed. Henry poured more tea for Rosa, took another Oreo for himself, and then was quiet for some time.

“It’s not a hard one to answer,” he said. “It’s just not something I like to think about, to be honest.”

“Well they sent this poor girl all the way from Boston, so you better answer.”

“It’s ugly, I guess,” he said, his voice wavering.

“Go ahead.”

“That I won’t die first is my fear. That I’ll be left here without you.”

At the corner of Bulfinch Triangle in Boston’s West End, not far from where Henry Keane lived as a child, the Lockhart Building overlooks the noisy convergence of Merrimac and Causeway Streets. In the early twentieth century this stubborn brick structure was a furniture factory, and employed men and women from Henry’s neighborhood. Now it’s home to medical offices, a local pizzeria, and a donut shop. It’s also home to the researchers and the records of the Harvard Study of Adult Development, the longest study of adult life ever conducted.

Nestled near the back of a file drawer labeled “KA–KE” are Henry’s and Rosa’s files. Inside we find the yellowed pages, crumbling at the edges, of Henry’s 1941 intake interview. It is written in longhand, in the interviewer’s flowing, practiced cursive. We see that his family was among the poorest in Boston, that at age 14 Henry was seen as a “stable, well-controlled” adolescent, with “a logical regard for his future.” We can see that as a young adult he was very close to his mother, but resented his father, whose alcoholism forced Henry to be the primary breadwinner. In one particularly damaging incident when Henry was in his 20s, his father told Henry’s new fiancée that her $300 engagement ring had deprived the family of needed money. Fearing she would never escape his family, his fiancée called off the engagement.

In 1953 Henry broke free of his father when he got a job with General Motors and moved to Willow Run, Michigan. There he met Rosa, a Danish immigrant and one of nine children. One year later they were married and would go on to have five children of their own. “Plenty, but not enough,” in Rosa’s opinion.

Over the next decade Henry and Rosa would experience some difficult times. In 1959 their five-year-old son, Robert, contracted polio, a challenge that tested their marriage and caused a great deal of pain and worry in the family. Henry began at GM on the factory floor as an assembler, but after missing work due to Robert’s illness he was demoted, then laid off, and at one point found himself unemployed with three children to care for. To make ends meet, Rosa began working for the city of Willow Run, in the payroll department. While the job was initially a stopgap for the family, Rosa became much loved by her coworkers, and she worked full-time there for the next thirty years, developing relationships with people she came to think of as her second family. After being laid off Henry changed careers three times, finally returning to GM in 1963, and working his way up to floor supervisor. Shortly after, he reconnected with his father (who had managed to overcome his addiction to alcohol) and forgave him.

Henry and Rosa’s daughter, Peggy, now in her 50s, is also a participant in the Study. Peggy does not know what her parents have shared with the Study because we do not want to bias her reports about her family life. Having multiple perspectives on the same family environment and the same events helps broaden and deepen the Study’s data. When we dig into Peggy’s file, we learn that when she was growing up, she felt her parents understood her problems, and that they helped cheer her up when she was upset. In general, she saw her parents as “very affectionate.” And consistent with Henry’s and Rosa’s own reports about their marriage, Peggy said that her parents never considered separation or divorce.

In 1977, at age 50, Henry rated his life this way:

Enjoyment of marriage: EXCELLENT

Mood over the past year: EXCELLENT

Physical health over the past 2 years: EXCELLENT.

But we don’t determine Henry’s health and happiness, or anyone’s in the Study, simply by asking them and their loved ones how they feel. Study participants allow us to look at their well-being through many different lenses, including everything from brain scans to blood tests to videotapes of them talking about their deepest concerns. We take samples of their hair to measure stress hormones, we ask them to describe their biggest worries and their critical goals in life, and we measure how quickly their heart rates calm down after we challenge them with brain teasers. This information gives us a deeper and fuller measurement of how someone is doing in their life.

Henry was a shy man, but he devoted himself to his closest relationships, in particular to his connection with Rosa and his children, and these connections provided him with a deep sense of security. He also employed certain powerful coping mechanisms that we will discuss in the coming pages. Building on this combination of emotional security and effective coping, Henry could report over and over again that he was “happy” or “very happy,” even during his hardest times, and his health and longevity reflect that.

In 2009, five years after Charlotte’s visit to Henry and Rosa’s home, and seventy-one years after his first interview with the Study, Henry’s greatest fear came true: Rosa passed away. Less than six weeks later, Henry followed.

But the family legacy continues in their daughter, Peggy. Just recently, she sat down for an interview at our offices in Boston. Since the age of 29 Peggy has been in a happy relationship with her partner, Susan, and now, at age 57, reports no loneliness and good health. She is a respected grade school teacher and an active member of her community. But the path she took to arrive at this happy time in her life is harrowing and courageous, and we’ll be returning to her later.

THE INVESTMENT OF A LIFETIME

What was it about Henry and Rosa’s approach to life that allowed them to flourish in the face of difficulty? And what makes Henry and Rosa’s story, or any of the life stories in the Harvard Study, worth your time and attention?

When it comes to understanding what happens to people as they go through life, pictures of entire lives—of the choices people make and the paths they follow, and how it all works out for them—are almost impossible to get. Most of what we know about human life we know from asking people to remember the past, and memories are full of holes. Just try to remember what you had for dinner last Tuesday, or who you spoke with on this date last year, and you’ll get an idea how much of our lives is lost to memory. The more time that passes, the more details we forget, and research shows that the act of recalling an event can actually change our memory of it. In short, as a tool for studying past events, the human memory is at its best imprecise, and at its worst, inventive.

But what if we could watch entire lives as they unfold through time? What if we could study people from the time that they were teenagers all the way into old age to see what really matters to a person’s health and happiness, and which investments really paid off?

We did that.

For eighty-four years (and counting), the Harvard Study has tracked the same individuals, asking thousands of questions and taking hundreds of measurements to find out what really keeps people healthy and happy. Through all the years of studying these lives, one crucial factor stands out for the consistency and power of its ties to physical health, mental health, and longevity. Contrary to what many people might think, it’s not career achievement, or exercise, or a healthy diet. Don’t get us wrong; these things matter (a lot). But one thing continuously demonstrates its broad and enduring importance:

Good relationships.

In fact, good relationships are significant enough that if we had to take all eighty-four years of the Harvard Study and boil it down to a single principle for living, one life investment that is supported by similar findings across a wide variety of other studies, it would be this:

Good relationships keep us healthier and happier. Period.

So if you’re going to make that one choice, that single decision that could best ensure your own health and happiness, science tells us that your choice should be to cultivate warm relationships. Of all kinds. As we’ll show you, it’s not a choice that you make only once, but over and over again, second by second, week by week, and year by year. It’s a choice that has been found in one study after another to contribute to enduring joy and flourishing lives. But it’s not always an easy one to make. As human beings, even with the best intentions, we get in our own way, make mistakes, and get hurt by the people we love. The path to the good life, after all, isn’t easy, but successfully navigating its twists and turns is entirely possible. The Harvard Study of Adult Development can point the way.

A TREASURE IN BOSTON’S WEST END

The Harvard Study of Adult Development began in Boston when the United States was fighting its way out of the Great Depression. As New Deal projects like Social Security and unemployment insurance gained momentum, there was a growing interest in understanding what factors made human beings thrive, as opposed to what factors made them fail. This new interest led two unrelated groups of researchers in Boston to initiate research projects closely following two very different groups of boys.

The first was a group of 268 sophomores at Harvard College, selected because they were deemed likely to grow into healthy and well-adjusted men. In the spirit of the time, but well ahead of his contemporaries in the medical community, Arlie Bock, Harvard’s new professor of hygiene and chief of Student Health Services, wanted to move away from a research focus on what made people sick to a focus on what made people healthy. At least half of the young men chosen for the study were able to attend Harvard only with the aid of scholarships and by holding down jobs to help pay tuition, and some came from well-to-do families. Some could trace their roots in America to the founding of the country, and 13 percent of them had parents who had immigrated to the U.S.

The second was a group of 456 inner-city Boston boys like Henry Keane, selected for a different reason: they were children who grew up in some of Boston’s most troubled families and most disadvantaged neighborhoods, but who, at age 14, had mostly succeeded in avoiding the paths to juvenile delinquency that some of their peers were following. More than 60 percent of these adolescents had at least one parent who immigrated to the U.S., most from poor areas of Eastern and Western Europe and areas in or near the Middle East, such as Greater Syria and Turkey. Their modest roots and immigrant status made them doubly marginalized. Sheldon and Eleanor Glueck, a lawyer and a social worker, respectively, initiated this study in an attempt to understand which life factors prevented delinquency, and these boys had succeeded on that front.

These two studies began separately and with their own aims, but were later merged, and now operate under the same banner.

When they joined their respective studies, all of the inner-city and Harvard participants were interviewed. They were given medical exams. Researchers went to their homes and interviewed their parents. And then these teenagers grew up into adults who entered all walks of life. They became factory workers and lawyers and bricklayers and doctors. Some developed alcoholism. A few developed schizophrenia. Some climbed the social ladder from the bottom all the way to the very top, and some made that journey in the opposite direction.

The founders of the Harvard Study would be shocked and delighted to see that it still continues today, generating unique and important findings they couldn’t have imagined. And as the current director (Bob) and associate director (Marc), we are incredibly proud to bring some of these findings to you.

A LENS THAT CAN SEE THROUGH TIME

Human beings are full of surprises and contradictions. We don’t always make sense, even (or maybe especially) to ourselves. The Harvard Study gives us a unique and practical tool to see through some of this natural human mystery. Some quick scientific context will help explain why.

Studies of human health and behavior generally come in two flavors: “cross-sectional” and “longitudinal.” Cross-sectional studies take a slice out of the world at a given moment and look inside, much the way you might cut into a layer cake to see what it’s made of. Most psychological and health studies fall into this category because they are cost efficient to conduct. They take a finite amount of time and have predictable costs. But they have a fundamental limitation, which Bob likes to illustrate with the old joke that if you relied only on cross-sectional surveys, you’d have to conclude that there are people in Miami who are born Cuban and die Jewish. In other words, cross-sectional studies are “snapshots” of life, and can prompt us to see connections between two unconnected things because they omit one crucial variable: time.

Longitudinal studies, on the other hand, are what they sound like. Long. They examine lives through time. There are two ways to do this. The first we’ve already mentioned, and it’s the most common: you ask people to remember the past. This is known as a retrospective study.

But as we mentioned, these studies rely on memory. Take Henry and Rosa. During their individual interviews in 2004, Charlotte asked each of them, separately, to describe the first time they met. Rosa recounted how she’d slipped on the ice in front of Henry’s truck, how Henry helped her up, and how she later saw him in a restaurant when she was out with some of her friends.

“It was funny, and we had a laugh about it,” Rosa said, “because he was wearing two different colors of socks, and I thought, ‘Boy he’s in bad shape, he needs somebody like me!’?”

Henry also remembered Rosa slipping on the ice.

“Then I saw her sitting in a café sometime later,” he said, “and she caught me staring at her legs. But I was only looking because she was wearing two different colors of stockings, red and black.”

This kind of disagreement among couples is common, and probably familiar to anyone who’s been in a long-term relationship. Well, anytime you and your partner disagree about the facts of your life together, you are witnessing the failure of a retrospective study.

The Harvard Study is not retrospective, it is prospective. Our participants are asked about their life as it is, not as it was. As in Henry and Rosa’s case, we do sometimes ask about the past in order to study the nature of memory, how events are processed and remembered in the future, but in general we want to know about the present. In this case, we actually know whose version of the socks/stockings story is more correct, because we asked Henry the same question about meeting Rosa the year they got married.

“I was wearing different color socks, and she noticed,” he said in 1954. “She wouldn’t let that happen today.”

Prospective, life-spanning studies like this are exceedingly rare. Participants drop out, change their names, or move without notifying the study. Funding dries up, researchers lose interest. On average, most successful prospective longitudinal studies maintain 30 to 70 percent of their participants. Some of these studies only last several years. By hook and by crook the Harvard Study has maintained an 84 percent participation rate for 84 years, and it’s still in good health today.

A LOT OF QUESTIONS. REALLY. A LOT.

Each life story in our longitudinal study is built on a foundation of the participant’s health and habits; a map of the physical facts and behaviors of their life, through time. To create a complete story of their health we gather regular information on weight and amount of exercise, smoking and drinking habits, cholesterol levels, surgeries, complications. Their entire health record. We also record other basic facts, like the nature of their employment, their number of close friends, their hobbies and recreational activities. At a deeper level we design questions to probe their subjective experience and the less quantifiable aspects of their lives. We ask about job satisfaction, marital satisfaction, methods of resolving conflicts, the psychological impact of marriages and divorces, childbirths and deaths. We ask about their warmest memories of their mothers and fathers, their emotional bonds (or lack thereof) with siblings. We ask them to describe for us in detail the lowest moments of their lives, and to tell us who, if anyone, they could call if they woke up frightened in the middle of the night.

We study their spiritual beliefs and political preferences, their church attendance and participation in community activities, their goals in life and their sources of worries. Many of our participants went to war, fought and killed and saw their friends killed; we have their firsthand accounts and reflections on these experiences.

Every two years we send lengthy questionnaires that include room for open-ended and personalized responses, every five years we collect complete health records from their doctors, and every fifteen years or so we meet them face-to-face on, say, a porch in Florida, or in a coffee shop in northern Wisconsin. We take notes on how they look and behave, their level of eye contact, their clothes, and their living conditions.

We know who developed alcoholism, and who is in recovery. We know who voted for Reagan, who voted for Nixon, who voted for John Kennedy. In fact, before his records were acquired by the Kennedy Library, we knew who Kennedy voted for, because he was one of our participants.

We’ve always asked how their children are doing, if they had them. Now we are asking the children themselves—women and men who are baby boomers—and one day we hope to ask their children’s children.

We have blood samples, DNA samples, and reams of EKG, fMRI, EEG, and other brain imaging reports. We even have twenty-five actual brains, donated by participants in a final act of generosity.

What we cannot know is how, or even if, these things will be used in future studies. Science, like culture, is ever-evolving, and while most of the data from the Study’s past have proven useful, some of the most carefully measured variables early on were studied only because of profoundly flawed assumptions.

In 1938, for example, body type was considered an important predictor of intelligence and even life satisfaction (mesomorphs—or the athletically built—were believed to have advantages in most areas). The shape and protuberances of the skull were thought to signify personality and mental capacities. One of the initial intake questions was, for reasons unknown, “Are you ticklish?” and we continued asking that question for forty years, just in case.

With eight decades of hindsight we now know that these ideas range from vaguely harebrained to downright wrong. It is possible, or even likely, that some of the data we are gathering today will be seen with similar bemusement or misgiving eighty years from today.

The point is that every study is a product of its time and the human beings who conduct it. In the case of the Harvard Study, those human beings were mostly White, middle-aged, educated, heterosexual, and male. Because of cultural biases and the almost entirely White makeup of both the City of Boston and Harvard College in 1938, the Study founders took the convenient route of studying only other White males. It’s a common story, one that the Harvard Study must grapple with, even as we work to correct it. And though there are findings that apply only to one or both of the groups that began the Study in the 1930s, those narrow findings do not feature in this book. Fortunately, we can now compare the findings of the original Harvard Study sample with our own expanded sample (which includes the wives, sons, and daughters of our original participants) and also with studies that include people with more diverse cultural and economic backgrounds, gender identities, and ethnicities. In the coming pages we will emphasize the findings that other studies corroborate—findings that have been shown to be true for women, for people of color, for those identifying as LGBTQ+, for a full range of socioeconomic groups globally—for all of us. The aim of this book is to offer what we have learned about the human condition, to show you what the Harvard Study has to say about the universal experience of being alive.

Marc has taught at a women’s college for over twenty-five years, and each year a new cohort of bright, excited students ask to participate in his research on well-being and how people’s lives evolve across time. Ananya, from India, was one of these students. She was interested particularly in the links between adversity and adult well-being. Marc told Ananya about the Harvard Study’s rich data on hundreds of people spanning their entire adult lives. But they were male, White, and born more than seven decades before Ananya. She wondered out loud what she could learn from the lives of people so different from her—especially old White men born a long time ago.

Marc suggested she spend the weekend reading through the files of just one participant from the Harvard Study, and then they could talk again the following week. Ananya came to the next meeting full of enthusiasm, and before Marc could even ask, said she wanted to do her research on the men in the Harvard Study. What persuaded her was the richness of the life documented in the files she read. Even though the particulars of this one participant’s life were so different from her own in so many ways—he came of age on a different continent, lived life with white rather than brown skin, identified as a man not a woman, never went to college—Ananya saw reflections of herself in his psychological experiences and challenges.

This is a story that has repeated itself almost every year; even more so in the last few years as psychology and the world beyond it have reckoned with serious ongoing disparities related to ethnic and cultural backgrounds. Bob himself experienced a similar hesitation when he was first asked to join the Harvard Study as its new director. He, too, had doubts about the relevance of these lives and the quaintness of some of its research methods. He took a weekend to read through a few of the files and was hooked immediately, just as Ananya was. Just as we hope you will be.

An entire century has passed since our First Generation participants were born, but humans are as complex as always, and the work is never over. As the Harvard Study forges ahead into the next decade, we continue to refine and expand our collection of information with the idea that each piece of data, each personal reflection or in-the-moment feeling, creates a more complete picture of the human condition and may help answer questions in the future that we cannot currently envision. Of course, no picture of a human life can ever be complete.

But we hope you’ll come with us as we wade into some of the most elusive questions about human development. For example: Why do relationships seem to be the key to a flourishing life? What factors in early childhood shape physical and mental health in mid and late life? What factors are most strongly associated with longer lifespans? Or with healthy relationships? In short:

WHAT MAKES A GOOD LIFE?

When asked what they want out of life, one thing many people say is that they simply want to “be happy.” If he’s honest, Bob might answer that question for himself in the same way. It’s impossibly vague and yet somehow says it all. Marc would probably take a second and then say, “It’s more than that.”

But what does happiness mean? What would it look like in your life?

One way to find some answers to this question might be to simply ask people what would make them happy, and then find commonalities. But, as we’ll show, one hard truth that we would all do well to accept is that people are terrible at knowing what is good for them. We’ll get into that later.

More important than how people would answer the question are the unspoken and internalized myths about what makes a happy life. There are many, but chief among these myths is the idea that happiness is something you achieve. As if it were an award you could frame and hang on the wall. Or as if it were a destination, and after overcoming all of the obstacles in your way, you will finally arrive there, and then just hang out for the rest of your life.

Of course, it doesn’t work that way.

More than two thousand years ago Aristotle used a term that is still in wide use in psychology today: eudaimonia. It refers to a state of deep well-being in which a person feels that their life has meaning and purpose. It is often contrasted with hedonia (the origin of the word hedonism), which refers to the fleeting happiness of various pleasures. To put it another way, if hedonic happiness is what you mean when you say you’re having a good time, then eudaimonic happiness is what we mean when we say life is good. It is a sense that, outside of this moment, regardless of how pleasurable or miserable it is, your life is worth something, and valuable to you. It is the kind of well-being that can endure through both the ups and the downs.

Don’t worry, we won’t be saying “your eudaimonic happiness” over and over. But a quick word about what we will be saying, and what it means.

Some psychologists object to the word “happiness” because it can mean anything from a temporary pleasure to an almost mythical sense of eudaimonic purpose that few in reality manage to reach. So in lieu of happiness, more nuanced terms like “well-being,” “wellness,” “thriving,” and “flourishing” have become common in the popular psychological literature. We use those terms in this book. Marc is particularly fond of the terms thriving and flourishing because they refer to an active and constant state of becoming, rather than just a mood. But we still use “happiness” at times for the simple reason that this is how people talk about their lives. Nobody says, “How’s your human flourishing?” We say, “Are you happy?” And it’s how, in casual conversation, we both find ourselves talking about our research as well. We talk about health and happiness, meaning and purpose. But we mean eudaimonic happiness. And despite the uncertainty about the word, when people stop to think about what it really means, it’s a natural term. When a couple describe their new grandchild and say, “We’re very happy,” or when someone in therapy describes her marriage as “unhappy,” it’s clear the word refers to an enduring quality of life, not just a passing feeling. That is the spirit in which we use the term in this book.

FROM THE DATA TO YOUR DAILY LIFE

You might be wondering how we can be so sure that relationships play such a central role in our health and happiness. How is it possible to separate relationships from economic considerations, from good or bad luck, from difficult childhoods, or from any of the other important circumstances that affect how we feel from day to day? Is it really possible to answer the question, What makes a good life?

After studying hundreds of entire lives, we can confirm what all of us already know deep down—that a huge range of factors contribute to a person’s happiness. The delicate balance of economic, social, psychological and health contributors is complex and everchanging. Rarely can any single factor be said, with absolute confidence, to cause any single result, and people will always surprise you. That said, there really are answers to this question. If you look at the same kinds of data repeatedly over time, across large numbers of people and studies, patterns begin to emerge, and predictors of human thriving become clear. Among the many predictors of health and happiness, from good diet to exercise to level of income, a life of good relationships stands out for its power and consistency.

The Harvard Study is not the only multidecade longitudinal study of human psychological thriving in the world, and we consistently and deliberately look to other studies to see if findings are robust across different eras and different kinds of people. Each study has its own idiosyncrasies, so replication of findings across multiple studies is scientifically compelling.

A few significant examples of other longitudinal studies that collectively represent tens of thousands of people:

The British Cohort Studies include five large, nationally representative groups born in particular years (beginning with a group of baby boomers born just after World War II and most recently including a group of children born at the start of the current millennium) and have followed them across their entire lives.

The Mills Longitudinal Study has followed a group of women since their high school graduation in 1958.

The Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study began studying 91 percent of the children born in a small New Zealand city in 1972 and continues to follow them into middle age (and more recently to follow their children).

The Kauai Longitudinal Study ran for three decades and included all of the children born on the Hawaiian island of Kauai in 1955, most of whom were of Japanese, Filipino, and Hawaiian heritage.

The Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study (CHASRS), begun in 2002, intensively studied a diverse group of middle-aged men and women for more than a decade.

The Healthy Aging in Neighborhoods of Diversity Across the Life Span (HANDLS) study has been examining the nature and sources of health disparities in thousands of Black and White adults (aged 35–64) in the city of Baltimore since 2004.

Finally, in 1947, the Student Council Study began tracking the lives of women and men who were elected student council representatives at Bryn Mawr, Haverford, and Swarthmore colleges. This study was planned in part by researchers who had developed the Harvard Study, and was explicitly designed to capture the experience of women, who were not included in the original Harvard Study sample. It lasted more than three decades, and the original archival materials from that study were recently rediscovered. Because of the Student Council Study’s connection with the Harvard Study, you will get to meet some of these women in this book.

All of these studies, as well as our own Harvard Study, bear witness to the importance of human connections. They show that people who are more connected to family, to friends, and to community, are happier and physically healthier than people who are less well connected. People who are more isolated than they want to be find their health declining sooner than people who feel connected to others. Lonely people also live shorter lives. Sadly, this sense of disconnection from others is growing across the world. About one in four Americans report feeling lonely—more than sixty million people. In China, loneliness among older adults has markedly increased in recent years, and Great Britain has appointed a minister of loneliness to address what has become a major public health challenge.

These are our neighbors, our children, ourselves. There are myriad social, economic, and technological reasons for this, but regardless of the causes, the data could not be clearer: the shadow of loneliness and social disconnection haunts our modern “connected” world.

You may be asking right now if anything can actually be done about your own life. Are the qualities that make us social or shy just baked into our personalities? Are we destined to be loved or lonely, destined to be happy or unhappy? Do our childhood experiences define us, forever? We get asked questions like this a lot. Really, most of them boil down to this fear: Is it too late for me?

It’s something the Harvard Study has worked hard to answer. The previous director of the Study, George Vaillant, spent a considerable amount of his career studying whether the ways that people respond to life challenges—the ways they cope—can change. Thanks to George’s work and the work of others, we can say that the answer to that enduring question, Is it too late for me? is a definitive NO.

It is never too late. It’s true that your genes and your experiences shape the way you see the world, the way you interact with other people, and the way you respond to negative feelings. And it is certainly true that opportunities for economic advancement and basic human dignity are not equally available to all, and some of us are born into positions of significant disadvantage. But your ways of being in the world are not set in stone. It’s more like they are set in sand. Your childhood is not your fate. Your natural disposition is not your fate. The neighborhood you grew up in is not your fate. The research shows this clearly. Nothing that has happened in your life precludes you from connecting with others, from thriving, or from being happy. People often think that once you get to adulthood, that’s it—your life and your way of living are set. But what we find by looking at the entirety of research into adult development is that this just isn’t true. Meaningful change is possible.

We used a particular phrase a moment ago. We talked about people who are more isolated than they want to be. We use this phrase for a reason; loneliness is not only about physical separation from others. The number of people you know does not necessarily determine your experience of connectedness or loneliness. Neither do your living arrangements or your marital status. You can be lonely in a crowd, and you can be lonely in a marriage. In fact, we know that high-conflict marriages with little affection can be worse for health than getting divorced.

Instead, it is the quality of your relationships that matters. Simply put, living in the midst of warm relationships is protective of both mind and body.

This is an important concept, the concept of protection. Life is hard, and sometimes it comes at you in full attack mode. Warm, connected relationships protect against the slings and arrows of life and of getting old.

Once we had followed the people in the Harvard Study all the way into their 80s, we wanted to look back at them at midlife to see if we could predict who was going to grow into a happy, healthy octogenarian and who wasn’t. So we gathered together everything we knew about them at age 50 and found that it wasn’t their middle-aged cholesterol levels that predicted how they were going to grow old; it was how satisfied they were in their relationships. The people who were the most satisfied in their relationships at age 50 were the healthiest (mentally and physically) at age 80.

As we investigated this connection further, the evidence continued to grow. Our most happily partnered men and women reported, in their 80s, that on the days when they had more physical pain, their mood stayed just as happy. But when people in unhappy relationships reported physical pain, their mood worsened, causing them additional emotional pain as well. Other studies come to similar conclusions about the powerful role of relationships. A few touchstone examples from some of the longitudinal studies mentioned above:

With a cohort of 3,720 Black and White adults (aged 35–64), the Healthy Aging in Neighborhoods of Diversity Across the Life Span (HANDLS) study found that participants who reported receiving more social support also reported less depression.

In the Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study (CHASRS), a representative study of Chicago residents, participants who were in satisfying relationships reported higher levels of happiness.

In the birth cohort study based in Dunedin, New Zealand, social connections in adolescence predicted well-being in adulthood better than academic achievement.

The list goes on. But of course, science is not the only area of human knowledge that has something to say about the good life. In fact, science is the newcomer.

THE ANCIENTS BEAT US TO IT

The idea that healthy relationships are good for us has been noted by philosophers and religions for millennia. In a certain way, it is remarkable that all through history people trying to understand human life keep coming to very similar conclusions. But it makes sense. Even though our technologies and cultures continue to change—more rapidly now than ever before—fundamental aspects of the human experience endure. When Aristotle developed the idea of eudaimonia, he was drawing on his observations of the world, yes, but also on his own feelings; the same feelings we experience today. When Lao Tzu said more than twenty-four centuries ago “The more you give to others, the greater your abundance” he was noting a paradox that is still with us. They were living at a different time, but their world is still our world. Their wisdom is our inheritance, and we should take advantage of it.

We note these parallels with ancient wisdom to put our science into a broader context and to highlight the eternal significance of these questions and findings. With a few exceptions, science has not been much interested in the ancients, or in received wisdom. Striking out on its own path after the Enlightenment, science has been like the young hero on a quest for knowledge and truth. It may have taken hundreds of years, but in the area of human well-being, we are now approaching a full circle. Scientific knowledge is finally catching up to the ancient wisdom that has survived the test of time.

THE BUMPY PATH OF DISCOVERY

Every day the two of us come to work to tackle the question of what makes a good life. As the years have gone on, some results have surprised us. Things we’ve assumed to be the case in fact were not. Things we assumed would be false have proven to be true. In the coming chapters, we’ll be sharing all of it—or a lot of it—with you.

In the next five chapters we explore the elemental nature of relationships and get specific about how to apply the book’s most powerful lessons. We talk about how knowing your perch in life—where you are in the human lifespan—can help you find meaning and happiness from day to day. We discuss the massively important concept of social fitness and why it’s just as crucial as physical fitness. We explore how curiosity and attention can improve relationships and well-being; and offer some strategies for how to deal with the fact that relationships also pose some of our greatest challenges.

In later chapters, we’ll dig into the nitty-gritty of specific types of relationships, from what matters in long-term intimacy, to how early family experience affects well-being and what to do about it, to the oft overlooked opportunities for connection in the workplace, to the surprising benefits of all types of friendships. And through it all we will share the science that these insights came from, and we’ll hear from Harvard Study participants about how all of these things have played out in their real lives, in real time, for nearly a century.

As director and associate director, we’ve focused our lives on the Harvard Study and what it can teach us about happiness. We are blessed (and afflicted) by a fascination with the human condition. Bob is a psychiatrist and psychoanalyst who spends hours every day talking with people about their deepest concerns. In addition to directing the Harvard Study, he teaches young psychiatrists how to do psychotherapy. He’s been married for thirty-five years, has two grown sons, and in his off hours spends a lot of time on a meditation cushion practicing and teaching Zen Buddhism. Marc is a clinical psychologist and professor who has been teaching and training new psychologists and researchers for thirty years. He, too, is a practicing therapist and is in a long marriage raising two sons. An avid sports fan, he’s often found during his off hours connecting with others on a tennis court (and in his younger days, on a basketball court).

The two of us began our research collaboration and friendship almost thirty years ago. We met at the Massachusetts Mental Health Center, an iconic community organization where we both worked with people struggling with mental illness in a setting of tremendous social and economic disadvantage. Both of us felt called to understand the experiences of people from backgrounds very different from our own, both in our clinical work and in our research on lives through time.

Thirty years later, we find ourselves still friends, still collaborating on research, and doing our best to shepherd the Harvard Study’s vast treasure trove of life stories toward its second century. In learning about these individuals and their families, we’ve also learned, and continue to learn, valuable lessons about ourselves, and how to conduct our own lives. This book is an attempt to share those lessons, and to share the priceless gift the Harvard Study’s participants have given the world. After all, they didn’t agree to participate merely for the sake of researchers like us. They did it for everyone, everywhere. Their lives form the beating heart of this book.

Already we have seen the results of bringing these insights to the larger world. In the course of our careers with the Study, we’ve given hundreds of lectures on the findings that we’ll share in the coming chapters, and we’ve marshaled everything we’ve learned into our Lifespan Research Foundation, a nonprofit dedicated to bringing the wisdom of lifespan development out of academic journals and into tools that people can use to better their lives. Over and over, people have approached us after lectures and workshops to say they feel a great relief hearing what we’ve learned, because the lessons make something abundantly clear: The good life is not always just out of reach after all. It is not waiting in the distant future after a dreamy career success. It’s not set to kick in after you acquire some massive amount of money. The good life is right in front of you, sometimes only an arm’s length away. And it starts now.

Product Details

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster (January 7, 2025)

- Length: 352 pages

- ISBN13: 9781982166700

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

“Robert Waldinger and Marc Schulz lead us on an empowering quest towards our greatest need: meaningful human connection. Blending research from an ongoing 80-year study of life satisfaction with emotional storytelling proves that ancient wisdom has been right all along – a good life is built with good relationships.”

– Jay Shetty, bestselling author of Think Like a Monk and host of the podcast On Purpose

“In a crowded field of life advice and even life advice based on scientific research, Schulz and Waldinger stand apart. Capitalizing on the most intensive study of adult development in history, they tell us what makes a good life and why.”

– Angela Duckworth, author of Grit, Christopher H. Browne Distinguished Professor of Psychology, University of Pennsylvania, co-founder and CEO of Character Lab

"Want the secret to the good life? Robert Waldinger and Marc Schulz give it to you in this magnificent new book. Based on the longest survey ever conducted over people’s lives, The Good Life reveals who winds up happy, who doesn’t, and why—and how you can use this information starting today."

– Arthur C. Brooks, Professor, Harvard Kennedy School and Harvard Business School, and #1 New York Times bestselling author

“Waldinger and Schulz are world experts on the counterintuitive things that make life meaningful. Their book will provide welcome advice for a world facing unprecedented levels of unhappiness and loneliness.”

– Laurie Santos, PhD, Chandrika and Ranjan Tandon Professor of Psychology at Yale University and host of the podcast The Happiness Lab podcast

“The Good Life tells the story of a rare and fascinating study of lives over time. This insightful, interesting, and well-informed book reveals the secret of happiness—and reminds us that it was never really a secret, after all.”

– Daniel Gilbert, author of the New York Times best-seller Stumbling on Happiness; and host of the PBS television series This Emotional Life

“Waldinger and Schulz have written an essential — perhaps the essential — book on human flourishing. Backed by extraordinary research and packed with actionable advice, The Good Life will expand your brain and enrich your heart.”

– Daniel H. Pink, #1 New York Times bestselling author of The Power of Regret, Drive, and A Whole New Mind

“I'm beyond thrilled that Dr. Waldinger and Dr. Schulz are publishing the findings of the Harvard Study. Over the years, I've discussed their research and recommended Dr. Waldinger's TED talk around the world. I can hardly wait to recommend The Good Life. It's accessible, interesting, and grounded in research—and is bound to make a difference in the lives of millions."

– Tal Ben-Shahar, bestselling author of Being Happy: You Don't Have to Be Perfect to Lead a Richer, Happier Life, and Happier: Learn the Secrets to Daily Joy and Lasting Fulfillment

"This book is simply extraordinary. It weaves ‘hard data’ and enlightening case studies and interviews together seamlessly in a way that stays true to the science while humanizing it. And what an important lesson it teaches. It helps people to understand how they should live their lives, and also provides a spectacular picture of what psychology can be at its best. It is data driven, of course, but data are just noise without wise interpretation.”

– Barry Schwartz, author of Practical Wisdom (with Kenneth Sharpe) and Why We Work

Resources and Downloads

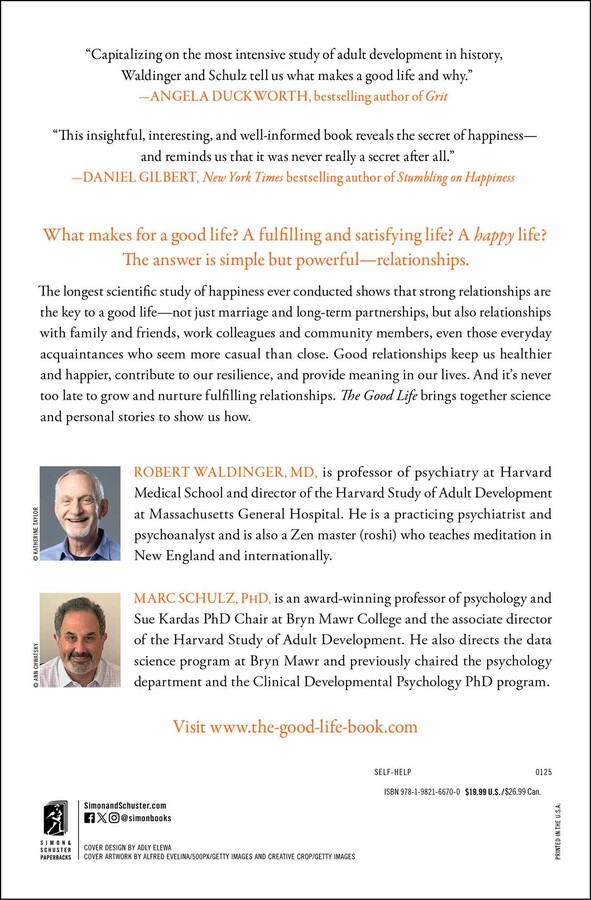

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): The Good Life Trade Paperback 9781982166700

- Author Photo (jpg): Robert Waldinger Photograph by Katherine Taylor(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit

- Author Photo (jpg): Marc Schulz Photograph by Ann Chwatsky(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit