Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

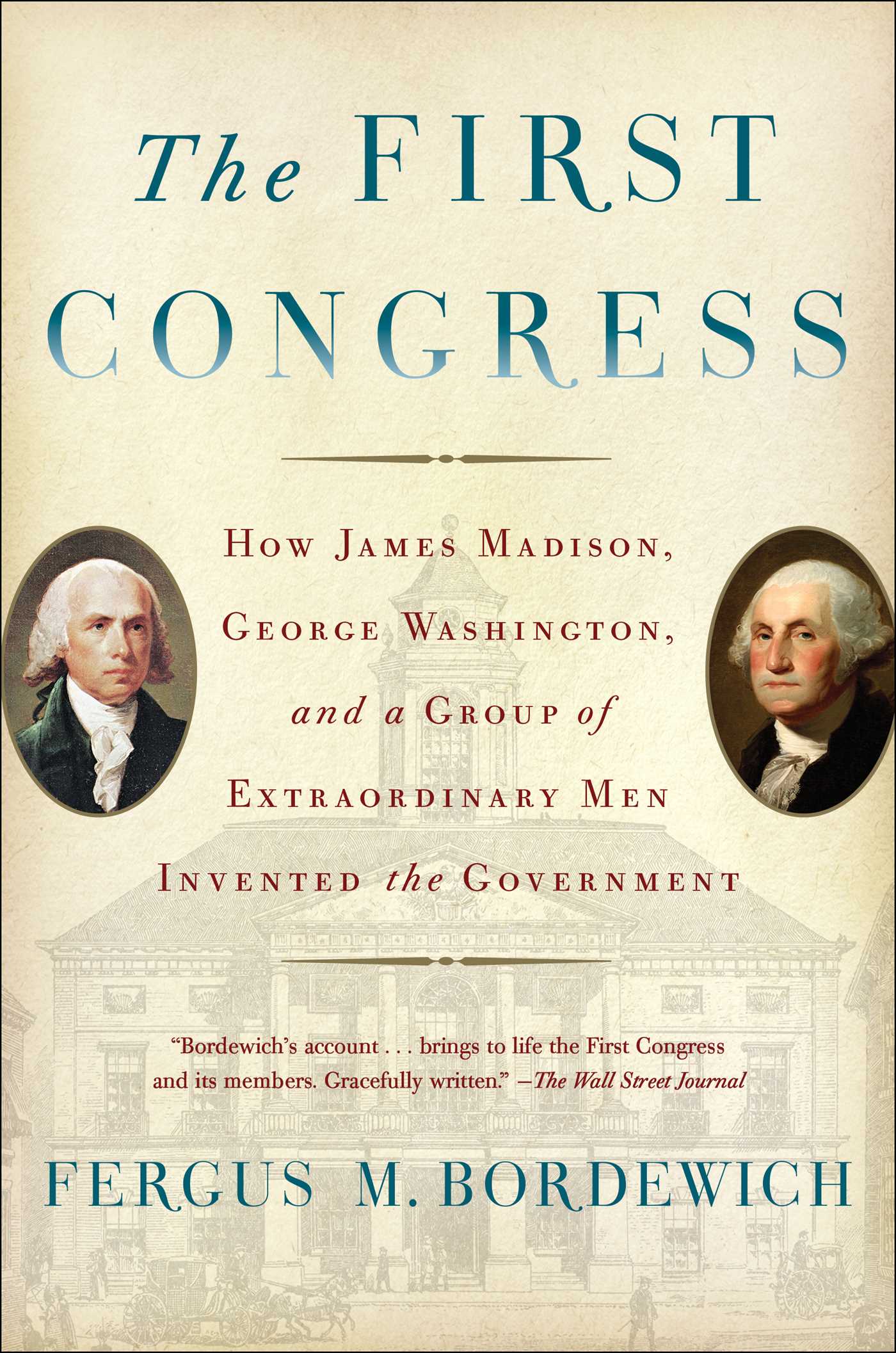

The First Congress

How James Madison, George Washington, and a Group of Extraordinary Men Invented the Government

Table of Contents

About The Book

The First Congress may have been the most important in American history because it established how our government would work. The Constitution was a broad set of principles that left undefined the machinery of government. Fortunately, far-sighted, brilliant, and determined men such as Washington, Madison, Adams, Hamilton, and Jefferson (and others less well known today) labored to create a functioning government.

In The First Congress, award-winning author Fergus Bordewich brings to life the achievements of the First Congress: it debated and passed the first ten amendments to the Constitution, which we know as the Bill of Rights; admitted North Carolina and Rhode Island to the union when they belatedly ratified the Constitution, then admitted two new states, Kentucky and Vermont, establishing the procedure for admitting new states on equal terms with the original thirteen; chose the site of the national capital, a new city to be built on the Potomac; created a national bank to handle the infant republic’s finances; created the first cabinet positions and the federal court system; and many other achievements. But it avoided the subject of slavery, which was too contentious to resolve.

The First Congress takes us back to the days when the future of our country was by no means assured and makes “an intricate story clear and fascinating” (The Washington Post).

Excerpt

Our Constitution is like a vessel just launched, and lying at the wharf; it is not known how she will answer her helm, or lay her course; whether she will bear in safety the precious freight to be deposited in her hold.

—Representative James Jackson of Georgia

Winter in the Potomac River Valley was unpredictable. Sheets of icy rain, sleet, and sometimes snow waterlogged much of the farmland around Alexandria and turned the roads into glutinous muck that played havoc with travelers’ schedules. One of those travelers, in late February of 1789, a diminutive figure bundled against the cold, had crossed Virginia from his home near the Blue Ridge Mountains to see a friend who was also the most famous man in America. As he approached George Washington’s Mount Vernon, James Madison would first have noticed the long avenue of broad-boughed, winter-bare oaks, and eventually the stately house itself, porticoed and colonnaded on its bluff overlooking the river. Madison was en route to New York City, to take up his duties in the new Congress that was about to come into being. Mount Vernon was out of his way. A more direct route would have taken him across the Potomac at Georgetown, Maryland, and from there directly to Baltimore. But Washington had summoned him, a trusted protégé who they both knew was likely to play a central role in the great debates that were to come. Denied one of Virginia’s Senate seats by his political opponents, Madison had just won a hard-fought contest against his friend James Monroe for a seat in the House of Representatives. Enemies of the Constitution, who were both passionate and powerful in Virginia, had warned that the election of Madison would produce “rivulets of blood throughout the land.” Fortunately such dire predictions did not come to pass.

Washington wanted help with his inaugural address, which the president-to-be would deliver in April. He had first entrusted the job to his aide David Humphreys, who had delivered a seventy-three-page behemoth of an oration full of policy proposals that expressed Washington’s support for a powerful federal government and an assertive executive. Madison told Washington, in essence, to toss Humphreys’s handiwork: it was too long and tried to say too much. Instead, he urged Washington to speak more simply to a fragile nation that was about to embark on a political experiment whose outcome few could see, and many feared. They dismembered and finally discarded Humphreys’s prolix draft and boiled down what Washington would say to the nation to essential ideas that every American could support. Drafting any address might have seemed like presumption on Washington’s part: he was not yet president. Voting for presidential electors was still taking place in several states—no citizen could cast a vote directly for president—and the results could not be officially declared until Congress met. But since he had no opposition, the outcome was a foregone conclusion.

The two men could hardly have been more dissimilar. At fifty-seven the aging war hero, a giant by the standards of his time, with his great beak of a nose, broad shoulders, and massive thighs that seemed to have been crafted by the Almighty to fit the back of a horse, was a living demigod. During the war, he had exhibited superhuman stoicism through the years of brutal winters, hunger, battlefield defeat, and civilian disaffection. He was also brave to the point of foolhardiness, repeatedly exposing himself to enemy fire; allegedly, at one point during the rout of American troops on Long Island, with a large rock in both hands, he was said to have stormed up to a boat filled with fleeing soldiers and threatened to “sink it to hell” unless the men went back to the fight. Popular writers commonly called him the nation’s “deliverer” and “savior” and occasionally even likened him to Jesus Christ. “O WASHINGTON! How do I love thy name!” declared Ezra Stiles, the president of Yale University, in a widely reprinted sermon. “How have I often adored and blessed thy God, for creating and forming thee the great ornament of human kind! Not all the gold of ophir, nor a world filled with rubies and diamonds, could effect or purchase the sublime and noble feelings of thine heart. Thy fame is of sweeter perfume than arabian spices in the gardens of persia.” His face, which appeared everywhere—on engravings, mezzotints, dinner plates, wall plaques, jugs, and mugs—was probably the only one that was known to virtually every American. Although he had publicly professed “the most unfeigned reluctance” to take on the presidency, Washington was, as one New Englander put it, “the only man which Man, Woman & Child, Whig & Tory, Fed’s and Antifed’s appear to agree in.”

Madison, twenty years Washington’s junior, was respected in political circles for his scholarship and persuasive powers, but not much loved. Sickly and slight—he stood five feet four and weighed only a hundred pounds—and deemed “unmanly” by many of his contemporaries, it seemed as if all his vigor had been sucked into his copious and muscular mind. The wife of one prominent Virginia politician dismissed him as “a gloomy, stiff creature . . . the most unsociable creature in Existence.” The two men had first met in 1781, when Madison was serving in the Continental Congress. Washington immediately recognized the Princeton-educated Madison as a young man of unusual talent. Although his wartime soldiering consisted only of a brief turn in the Virginia militia, his background in government was impressive. He had already served as a member of Virginia’s revolutionary convention, and then—still only in his midtwenties—as a political adviser to Governor Patrick Henry, and to Henry’s successor, Thomas Jefferson. After the war, as a member of the Virginia Assembly, Madison advocated for Washington’s commercial interests in the Potomac Valley and became one of the former general’s closest advisers.

Although Madison spoke in a whispery, often-difficult-to-hear voice, and without oratorical flourish, he consistently impressed those who worked with him with his “most ingenious mind,” and his mastery of parliamentary strategy. He understood, as many of his more emotional colleagues did not, his biographer Richard Brookhiser acutely observed, that “losing a vote was not the same as losing the argument, because if you could then write the guidelines for implementing the decision, you could nudge it in a better direction.” It was a lesson well learned at the Constitutional Convention, where Madison had unsuccessfully proposed, among other things, that the president be chosen by the legislative branch rather than by a popular vote channeled through an electoral college, that Congress be given the power to override state laws, and that the membership of both houses of Congress be based on population. Madison would carry with him to the First Congress a disdain for Pyrrhic moral victories, and a pragmatic determination to make the imperfect machine of government work.

Madison, more than any other man, had convinced the conflicted Washington first to attend the convention, and then to accept its chair. Washington would have preferred to remain at Mount Vernon beneath his “vine and fig tree,” his favorite euphemism for political disengagement, although he well knew that he could not remain so if the convention were to succeed. Though he shared Madison’s anxiety for the country, he feared that he would be accused of selfish ambition if he reentered public life, having so publicly proclaimed his official retirement from it in 1783. Madison, however—he was nothing if not persuasive, everyone agreed—made the case that no other American had the prestige to win nationwide support for a radical overhaul of the hapless Confederation government. Once committed, Washington was unshakable. Jefferson observed of him, “Perhaps the strongest feature in his character was prudence, never acting until every circumstance, every consideration, was maturely weighed; refraining if he saw a doubt, but, when once decided, going through with his purpose whatever obstacles opposed.” As Madison had hoped, Washington’s presence in Philadelphia helped to balance the discontent of those in the convention who felt that it was going too far in reinventing the government.

Madison’s reputation increased during the long campaign for ratification of the Constitution when, as a coauthor of The Federalist (with Alexander Hamilton and John Jay), he had laid out a reasoned case for a powerful central government, arguing that it would not weaken but strengthen personal liberties, and explaining to a doubtful public how its machinery would actually function. He boldly challenged the widely held belief that stable republics could work only in miniature societies, such as Greek city-states or homogeneous American communities. “Latent causes of faction”—that is, individual self-interest—he argued, was “sown in the nature of man,” and because it was inescapable, it had to be accommodated, not denied. This could best be accomplished in an extensive republic whose very diversity would prevent dangerous majorities from riding roughshod over political minorities, where it was less likely that any single party could outnumber and oppress the rest, and that a representative government rather than direct democracy would “refine and enlarge the public views, by passing them through the medium of a chosen body of citizens whose wisdom may best discern the true interest of their country.”

Like many political men at the time, Madison believed that the legislature would long remain the most powerful branch of government, and the most likely to suck “all power into its impetuous vortex.” To restrain the legislature’s greed for power, he maintained that all three branches of government had to be made equally vigorous and endowed with the “means and personal motives to resist encroachments of the others,” to prevent an accumulation of legislative power that would inexorably lead to tyranny. Mere “parchment barriers”—that is, well-meaning sentiments with no force to back them up—would not be enough. Dividing Congress itself into two branches vested with different powers was just a first step. The greater challenge was empowering the two weaker branches of government—the executive and judiciary—to resist legislative dictatorship. To this end, the president had been given a veto to protect the independence of the executive branch, while lifetime tenure for members of the Supreme Court would help insulate the judiciary from political interference. “Ambition must be made to counteract ambition,” he declared, in a famous formulation. “What is government itself but the greatest of all reflections on human nature? If men were angels, no government would be necessary.”

As election results for the new Congress trickled in from the states—there was no fixed day for elections—the results proved vastly more favorable than Washington, Madison, and their fellow supporters of the new Constitution had hoped. Federalists had won overwhelming majorities in both houses of Congress. Americans, in Washington’s opinion, had shown good sense, but the future remained fraught with risk. It might not take much to unravel the tentative fabric of a nation that had been rewoven at the Constitutional Convention less than two years earlier. “Some unforeseen mischance,” Washington worried, could still “blast [our] enjoyment in the very bud.”

The pressure on Washington was immense, and public expectations so high that he could never fully satisfy them, he knew. The president-to-be had received any number of importunate pleas from men such as John Armstrong Jr., a former member of the Continental Congress, who had begged him “to yield your services to the providential voice of God expressed in the voice of your country.” (Armstrong may have been one of the less convincing voices, however: In 1783, he had been a central figure in the so-called Newburgh Conspiracy, which toyed with the idea of a military coup against the Congress.) So many conflicting worries tore at Washington, both political and personal: the unrest on the frontier and the financial instability in the states, the resurgence of the Constitution’s opponents in Virginia, the planting schedules for his next season’s crops of wheat and rye, the challenge of managing the remote lands he owned in the West, the declining health of his eighty-year-old mother, who was dying of cancer at Fredericksburg. And now he was about to shoulder the unprecedented burdens of the presidency. To his neighbor Samuel Vaughn he confessed, as he doubtless did to Madison, “The event which I have long dreaded, I am at last constrained to believe, is now likely to happen. From the moment, when the necessity had become more apparent, & as it were inevitable, I anticipated in a heart filled with distress, the ten thousand embarrassments, perplexities & troubles to which I must again be exposed in the evening of a life, already near consumed in public cares.”

What was left of the old Confederation government was scheduled to cease functioning on March 3, and the new Congress to begin on March 4. But continuing wretched weather slowed Madison’s northward progress to a crawl. From Baltimore, he wrote Washington the happy news, reported to him by a courier from Georgia, that Federalists had triumphed in that state’s elections, too: “All the Candidates I understand are well affected to the Constitution.” But Madison’s spirits sank a few days later at Philadelphia, when a traveler from New York told him that only a handful of senators and congressmen had arrived there, and that neither New Jersey nor New York had even completed their elections. (The traveler, a planter whom Madison trusted, also delivered the ominous news that British agents were active in the trans-Appalachian Kentucky district of Virginia, agitating against the American government, a development that Madison knew would have to be dealt with.) Much more worried Madison as well during the long, muddy journey to New York: the country’s chaotic financial state . . . the angry veterans who everywhere were demanding back pay . . . the divisive debate raging over the site for a permanent federal capital . . . the numerous amendments that roiling popular conventions had demanded be made to the Constitution, which might well undo all the work that Madison had done. He also knew that popular hopes for the new government were unrealistically high. “The people,” wrote one Massachusetts voter, “are on tiptoe in their expectation from Congress, we expect more than Angells can do from your Body.”

From all over the eleven states that had approved the Constitution, newly elected members of Congress were heading, if glacially, toward New York. None of them knew with confidence whether they could rise to the demands of a new, untested government whose machinery they would have to invent as they went along. “Leaving my domestick peace and hapiness and plungeing into the Ocean of Publick Business, Politicks, and Etiquette is unaccountable even to Myself But the fates will have it so,” sighed Senator John Langdon of New Hampshire. Fisher Ames of Boston was so nervous at taking his seat in the House that it seemed like a kind of death. “I am about to leave and renounce this world and go to New York and must so far settle my worldly affairs as to be in a degree prepared for my future state (a state of terror and uncertainty to me),” he confided to a friend. One of Ames’s traveling companions, the much more experienced Elbridge Gerry, hardly knew what to expect either. He had been one of only three members of the Constitutional Convention who refused to sign the final document, and the sneering ridicule he had endured ever since left him depressed and discouraged. “You are now launching into the Ocean of Politics, an ocean always turbulent,” a supporter gently advised him. “I wish your habits & Experience may preserve you from Seasickness while the rectitude of your mind may lead you to stem the rolling Billows.”

New York City, in 1789, occupied only the southern tip of Manhattan Island and still bore the visible ravages of the seven-year British occupation during the Revolutionary War. There was no New Yorker who didn’t remember the overcrowding and starvation, the shortages, the streets torn up to build defensive works, the charred swathes of the city leveled by fire, the pathetic tent colonies of refugees, the harsh reprisals against rebels, the winters without firewood when the poor were found dead in their hovels at dawn. Even now, disintegrating forts and redoubts still punctuated the island’s rural landscape, while across the East River the bones of American soldiers killed during the 1776 battle for Long Island lay yellowing in plain sight.

As recently as June 1787, a visitor returning from several years in France had found the city still “in a state of prostration and decay.” Now, however, the city was roaring back to life. Everywhere, workmen were flattening hills, filling out the shoreline to create a new waterfront, erecting new houses, cutting new streets, constructing new docks. Business was thriving, trade on the rise, and the harbor a forest of tall-masted sailing ships from around the world. Although New York was the nation’s second city, with few buildings that rose higher than three stories, for the many members of Congress who hailed from rural areas, it was phantasmagorically cosmopolitan. Its doglegged lanes teemed with Hudson Valley Dutchmen, sailing men from the coast of New England, Jews and Frenchmen, Irishmen and Germans, frontiersmen from the backcountry of western New York, visiting Iroquois tribesmen, free blacks, slaves, and indentured white servants, who—like the enslaved—were forbidden to buy or sell, gamble or marry, or travel more than ten miles from their master’s home. The city’s newspapers were unfettered and combative. At the Merchant’s Coffee House at Wall and Water Streets, one might glimpse the politically potent young lawyers Aaron Burr or Alexander Hamilton amid the crowd of speculators, shipowners, importers, and traders in everything from real estate to slaves. In the surrounding business district, between Broadway and the East River docks, you could find whip makers and wigmakers, refiners of spermaceti and vendors of “nernous essence” for toothache, nurseries selling potted oleander and Arabian jasmine, retailers of tinderboxes, sleigh bells, quills, knee buckles, imported wines and liquors, publishers and printers, dancing masters to teach the latest European steps, and musicians such as the master “klokkenist and componist” Mr. Van Hagen willing to take on students. Even the city gallows was an astonishment, enshrined within a gaudily painted Chinese-style pagoda, next to the whipping post and stocks.

The city’s leading physician, the boosterish Samuel Bard, might gush over the city’s healthful location, surrounded by luxuriant farmland and blessed with “sweetening and salubrifying air.” But many members of Congress were appalled by the ubiquitous filth. The stink of rotting garbage was pervasive, while laundresses scrubbed the city’s linen on the shores of the Collect, a body of water near the present-day courthouses, both state and federal, where tanners dumped their chemicals amid floating effluvia that included dead cats and dogs, and rotting offal. Congressman John Page of Virginia disgustedly observed, “The Streets here are badly paved, very dirty & narrow as well as crooked, & filled up with a Strange Variety of wooden Stone & brick Houses & full of Hogs & mud.” And excrement. The poor simply dumped their chamber pots in the gutters, leaving it to rain and battalions of roaming, rooting hogs to deal with it. For the wealthy, sanitation (such as it was) devolved upon slaves: long lines of them could be seen in the dawn light trudging toward the river with tubs of plutocratic “night soil” on their heads.

Unfazed by such noisome realities, the pious Senator Oliver Ellsworth of Connecticut found New York reassuringly religion-minded, and well regulated. There were bans against sawing wood on the sidewalk, planting trees south of the Collect except in front of churches, and driving water carts any faster than a walk. Swearing was punishable by a fine of three shillings or imprisonment in the stocks; churches were plentiful and their pews were well filled. “And what has added to my pleasure,” Ellsworth wrote to his wife, Abigail, “has been the great decence & appearance of devotion with which divine service is attended. Instead of gazing, whispering & laughing, most of the Ladies, & many of the Gentlemen kneel at prayers on . . . benches in their seats with their heads inclined so as to conceal their faces.” Ellsworth apparently never noticed the whorehouses that jammed the lanes behind the docks just a few minutes’ stroll from his rooming house.

In contrast to the inhabitants of Quakery Philadelphia and straitlaced Boston, New Yorkers prided themselves on their taste for fashion. Women wore spectacular dresses luxuriantly displayed over hoops that were flattened fore and aft and stood out two feet on either side. Hairstyles were architectural confections that rose a foot or more in height and were festooned with lace and flowers. Congressional wives were dazzled by the array of fabrics available in local stores: lawns, chintzes, calicos, palampoors, fustians, dimities, armozeens, taffities, crepes, velvets, bombazeens, osnaburgs, ticklenburgs, shalloons, fearnaughts, and dozens of others that were unheard of in the backcountry of New Hampshire or Georgia. Puritanical Yankees were shocked at the bursting bodices of the local women, which they considered intolerably decadent, not to mention the outrageous behavior of the French ambassador, who affected American homespun clothing but lived openly in his embassy with a mistress who was also his sister-in-law. Others were offended by New Yorkers’ overly refined manners and incessant socializing. “The Tyrant Custom” particularly annoyed the austere Presbyterian sensibilities of Senator William Maclay of Pennsylvania, who sneered at women who accoutered themselves with “a bunch of Bosom and bulk of Cotton that never was warranted by any feminine appearance in nature” and walked bent forward at the middle “as if some disagreeable disorder prevented them from standing erect.”

Maclay detested not only New York’s inhabitants, congestion, dissipation, and outlandish prices, but even Federal Hall, which he derided as a waste of money, the epitome of New York ostentation, and no better than a “Great Baby House.” (This was a play on words: L’Enfant’s name meant “child.”) “With so many windows and doors, and corners and loop holes . . . all your Honorable Body may play bo-peep, hide and seek, or anything else, for a whole twelve-month in it, without being found out,” he wrote anonymously in the Federal Gazette. The majority of arriving legislators, however, were amazed at the hall’s harmonious redesign and elegant, up-to-date interiors. The facade included an arcade in the Tuscan style, while inside, the lofty vestibule was flagged with marble and led to an atrium roofed with a glass cupola that bathed the first-floor lobby in light. The octagonal House chamber, where many of the most dramatic debates would take place, was widely regarded as a masterpiece. This fifty-by-seventy-foot “representatives’ apartment,” as it was often called, rose two stories and was amply lit by six tall windows, three on each side, and embellished with fluted, Ionic columns arranged throughout the room. The members’ desks and chairs—each covered in blue damask that matched the curtains—formed a semicircle. The smaller upstairs Senate chamber—forty feet square and fifteen feet high—was adorned with graceful pilasters whose capitals had been designed by L’Enfant, and a light blue ceiling from which a sun and thirteen stars radiated over the senators. The oversize chair—some meaningfully referred to it as a “throne”—of the presiding officer, the vice president, was elevated three feet above the floor beneath a draped canopy of crimson damask. Only the House chamber provided galleries for spectators, who flocked in great numbers to hear debates that were regarded as great public entertainment; the deliberations of the self-consciously elitist Senate would not be open to the public until 1795.

On the evening of March 3, while Madison was still on the miry road from Virginia, the old Confederation was officially “fired out” by thirteen cannon posted at Fort George, at the foot of Broadway. Crowed one newspaper, “The Copartnership of Anarchy and Antifederalism being dissolved by the death of the concerned, the firm ceases to be.” At sunrise the next day, eleven guns—one for each of the states that had approved the Constitution—boomed out again across the New York harbor, along with more joyous tolling of bells. “The old government has gently fallen asleep, and the new one is waking into activity,” optimistically wrote Representative George Thatcher, who was a member of both. Church bells rang and rang, flags waved, crowds cheered in an atmosphere of uninhibited joy. The fourth of March 1789, predicted Pennsylvania senator and merchant prince Robert Morris, “will no doubt be hereafter Celebrated as a New Era in the Annals of the World.”

Morris had crossed the Hudson from New Jersey that morning, just in time to watch the national flag hoisted atop Federal Hall, and to mingle with the rejoicing mobs of citizenry. He had good reason to celebrate. He had done more than most men to bring the new nation into being during the Revolutionary War. As superintendent of finance for the Confederation Congress, he had almost single-handedly saved the revolutionary government from collapse by underwriting its expenses with his personal fortune. As a staunch Federalist he had high hopes for the new government. But he was also a hardheaded businessman and no sentimentalist. That morning on the streets of Manhattan, he saw further than many, if not most, of his euphoric compatriots. No matter how hard Congress struggled to do its duty, he wrote to his wife, Molly, “The Public’s expectation seems to be so highly wound up that I think disappointment must inevitably follow after a while. But you know well how impossible it is for Public measures to keep pace with the sanguine desires of the interested, the ignorant, and the inconsiderate parts of the Community.”

Product Details

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster (February 21, 2017)

- Length: 416 pages

- ISBN13: 9781451692112

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

“Fergus M. Bordewich has transformed the recent multivolume collection of sources on the First Federal Congress into a lively narrative. . . . The First Congress is a perfect example of what a very good writer can do with these raw materials.”

– Carol Berkin, The New York Times Book Review

"The First Congress faced its daunting agenda with resourcefulness. . . . [Bordewich] provides clear and often compelling analyses of the problems that required varying doses of compromise and persuasion. . . . Readers will enjoy this book for making an intricate story clear and fascinating."

– David S. Heidler, The Washington Post

“Fergus Bordewich paints a compelling portrait of the first, critical steps of the American republic, a perilous time when Congress – a body that has proved naturally contentious and short-sighted – had to be wise, and it was. The First Congress deftly blends many voices and stories into an elegant and gripping tale of a triumph of self-government.”

– David O. Stewart, author of Madison's Gift: Five Partnerships That Built America and The Summer of 1787: The Men Who Invented the Constitution

“Bordewich’s account is well worth reading and brings to life the First Congress and its members. Gracefully written. . . . Bordewich provides a balanced assessment of the many achievements of the First Congress, while not overlooking its shortcomings.”

– Mark G. Spencer, The Wall Street Journal

“The story of how these flawed but brilliant men managed to put the theory of the Constitution into actual practice and create a functioning government is the subject of Fergus M. Bordewich's fascinating The First Congress."

– Tom Moran, The Chicago Tribune

"With his highly informative The First Congress, historian Fergus M. Bordewich joins the ranks of familiar authors like Joseph Ellis, David McCullough, Fred Kaplan and others, whose biographies and studies of early American history have captivated so many. . . . Bordewich combines fascinating biography with a detailed account of the three sessions of Congress that ran from 1789-1791 and established the institutions and protocols that we follow today."

– Tony Lewis, The Providence Journal

“Entertaining. . . . The colorful machinations of our first Congress receive a delightful account that will keep even educated readers turning the pages.”

– Kirkus Reviews (starred review)

“Bordewich brings back to life the ‘practical, impatient, and tired politicians’ who transformed the parchment of the US Constitution into the flesh and blood of a national government. . . . Anyone curious about the origins of today’s much-maligned national legislature will marvel at this hair-raising story of stunning political creativity.”

– Richard A. Baker, US Senate Historian Emeritus and co-author of The American Senate: An Insider’s History

“Fergus Bordewich reminds us, with solid research and sprightly prose, that once upon a time Congress worked and leaders of the new nation understood that true patriotism requires that legislators actually get things done and keep the Government open for business. This book should be required reading for every member of Congress.”

– Paul Finkelman , Senior Fellow, University of Pennsylvania Program on Democracy, Citizenship, and Constitutionalism

“[A] highly readable and sweeping account of the First Federal Congress.”

– Kenneth R. Bowling, co-editor, First Federal Congress Project; Adjunct Professor of History, George Washington University; and author of Peter Charles L'Enfant

“Bordewich expertly conveys the excitement of how the first U.S. Congress(1789–91) created a government. . . . This engaging and accessible book sheds new light on themeaning of constitutionality.”

– Library Journal

“Finally, a popular and finely paced account of the Congress that could have easily unmade the new American republic.”

– Allen Guelzo, The Washington Monthly

"Bordewich’s telling of the debates around what we think of as the Bill of Rights is especially illuminating. . . . Bordewich brings these debates to life with fascinating and sympathetic portraits."

– Philip A. Wallach, The Brookings Institution

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): The First Congress Trade Paperback 9781451692112

- Author Photo (jpg): Fergus M. Bordewich Photograph by Jack Barschi(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit