Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

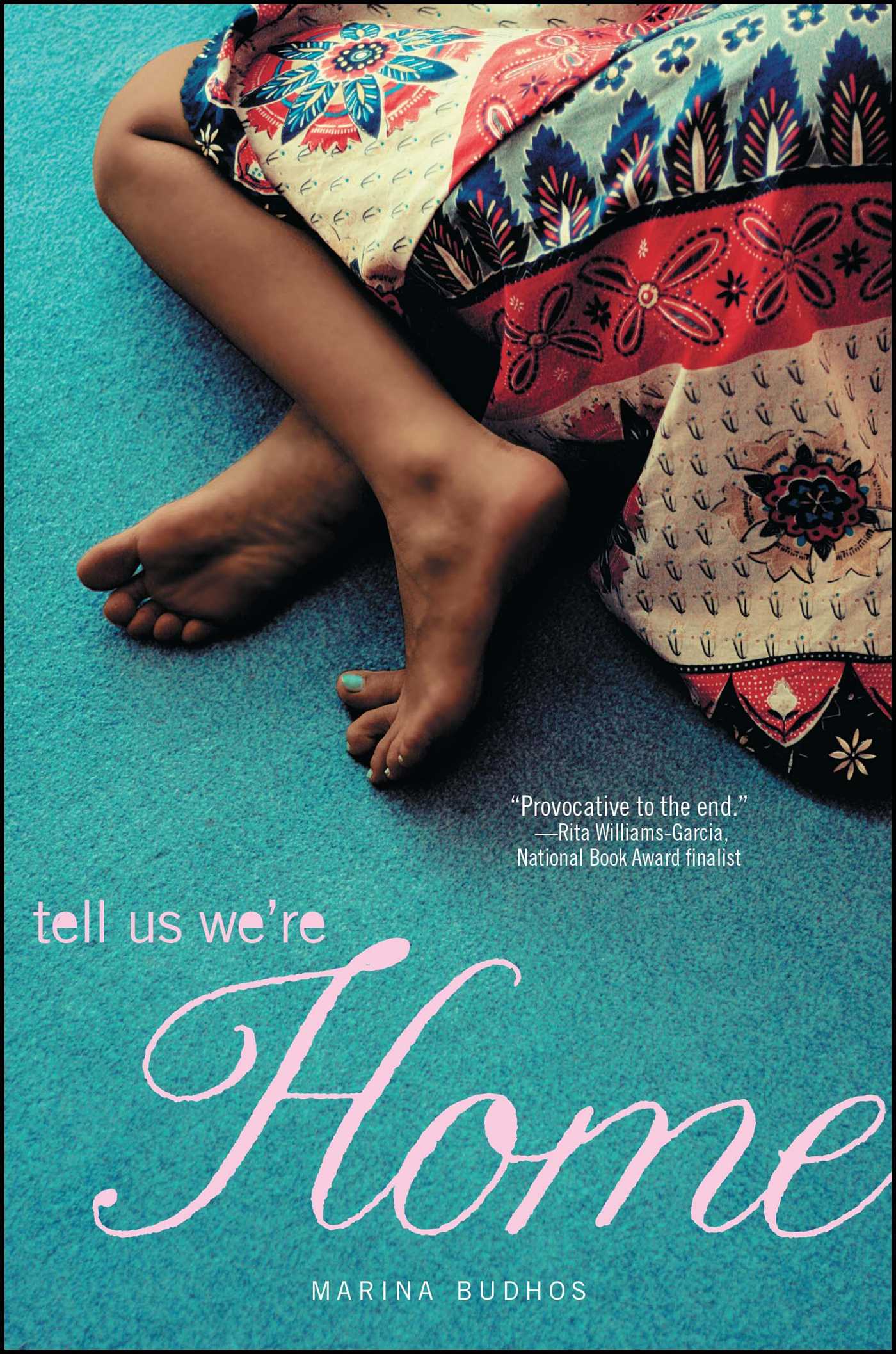

Tell Us We're Home

LIST PRICE $12.99

PRICE MAY VARY BY RETAILER

Get 30% off hardcovers with code MOM30, plus free shipping on orders of $40 or more. Terms apply.

Buy from Other Retailers

Table of Contents

About The Book

Jaya, Maria, and Lola are just like the other eighth-grade girls in the wealthy suburb of Meadowbrook, New Jersey. They want to go to the spring dance, they love spending time with their best friends after school, sharing frappés and complaining about the other kids. But there’s one big difference: all three are daughters of maids and nannies. And they go to school with the very same kids whose families their mothers work for.

That difference grows even bigger—and more painful—when Jaya’s mother is accused of theft and Jaya’s small, fragile world collapses.

When tensions about immigrants start to erupt, fracturing this perfect, serene suburb, all three girls are tested, as outsiders—and as friends. Each of them must learn to find a place for themselves in a town that barely notices they exist.

Marina Budhos gives us a heartbreaking and eye-opening story of friendship, belonging, and finding the way home.

That difference grows even bigger—and more painful—when Jaya’s mother is accused of theft and Jaya’s small, fragile world collapses.

When tensions about immigrants start to erupt, fracturing this perfect, serene suburb, all three girls are tested, as outsiders—and as friends. Each of them must learn to find a place for themselves in a town that barely notices they exist.

Marina Budhos gives us a heartbreaking and eye-opening story of friendship, belonging, and finding the way home.

Excerpt

chapter 1

Meadowbrook, New Jersey, looks like it’s right out of an old-time postcard. It has a big town hall, with huge columns and a neat border of red tulips. There’s a quaint little Main Street, its wrought-iron lampposts twined with evergreen sprigs at Christmas; a big green park, where the kids trace ice-skating loops on the frozen pond.

The town is nestled in a valley, and on one side is a steep incline that thrusts up into the ravine, where some of the expensive modern houses are perched like wood and glass boxes. On the other side the larger homes slowly give way to two-family houses and apartments on gritty Haley Avenue and to the big box stores of Route 12. More and more, shiny new condos have sprung up in the open gaps of land, a grove of pale brick McMansions standing where an old horse stable used to be.

Halfway up the hill, in the old section of town, is Mrs. Abigail Harmon’s house. It isn’t much of a house, as far as Meadowbrook houses go. More it’s a cottage, with a steep gabled roof and low exposed beams. The garden is a froth of eccentric tastes: pinwheels and tangled raspberry bushes, a crumbling slate wall and herb garden with chipped zigzagging paths. Mrs. Harmon inherited the place from her mother, who’d been born in the pink-wallpaper nursery, and whose grandfather once owned the hundred acres of farmland that makes up what is Meadowbrook today.

Around the time Mrs. Harmon was born, her family’s apple orchard was sold off to build the train station. Nowadays, when the early train draws up, a stream of women, mostly from the Caribbean or Latin America, step down in their rubber-soled shoes, cradling their Dunkin’ Donuts coffees, and make their way to the pretty clapboard houses. A few minutes later, up and down the streets, comes a chiming of voices, good-byes, slammed doors, cars backing down driveways, mothers and fathers rushing across town with their briefcases and still-wet hair to catch the next train to the city.

It was one of those not-quite-spring days, weak sun slanting through the drafty windows, and Mrs. Lal, the housekeeper at Mrs. Harmon’s place, was giving the vacuum one last firm push on the bedroom floor. Mrs. Lal stood tall at nearly six feet, black hair cropped short and stylish, showing her broad neck and shoulders. Mothers liked her because she gave them a tidy sense of everything in its place: children in bed by seven o’clock, no whining, no peas left behind on the plates.

Downstairs, Mrs. Lal’s daughter, Jaya, was sitting at the big table in the kitchen. She was supposed to be memorizing the periodic table. Really she was trying to work up the nerve to tell her mother about the middle school spring dance.

“Jaya!”

Jaya’s mother stood in the kitchen doorway, holding up three colored markers. “Jaya Lal, you have something against putting the tops on things?”

“Sorry.”

“How many times I have to tell you? This isn’t your house. You can’t just go mooning around like it’s yours. What’s Mrs. Harmon going to think of the way I’m raising you!”

“Okay, okay.”

In fact, what Jaya liked about Mrs. Harmon’s house was that she could treat it like hers. She didn’t have to say hello. Or good-bye. Mrs. Harmon just assumed she’d walk in if she felt like it. Of all her mother’s bosses, Mrs. Harmon was the only one who seemed to want Jaya there—she encouraged it. Make yourself at home. I’ve got too many rooms as it is. Jaya would spread out her homework at the nicked pine table or help herself to what was in the refrigerator, even though half the time the milk was well past its expiration date.

As Mrs. Lal was turning away, Jaya called out softly, “Mama?”

“Yes?”

Jaya hesitated. Shoved into her backpack was a bright pink flyer saying SPRING DANCE EXTRAVAGANZA! Quietly she handed the sheet to her mother, watching Mrs. Lal’s brow furrow while she read it. Usually Jaya didn’t bother showing her mother any of the permission slips for ski trips or overnights to Washington, D.C. She just threw them into the garbage. Even if there was some kind of disclaimer in tiny print at the bottom that the school would pay for those “in need.” No way was she going to sign up for that.

“It’s a really big deal.” Her voice quivered. “Me and my friends, we wanted to go.”

Her mother’s mouth made a tight line.

“And … I thought maybe I could get a new dress?”

“What’s wrong with that blue dress you bought last year?”

“That was last year.”

Silence fell as her mother kept standing in the doorway, the flyer clutched in her hand. Jaya could hear her mother go on: Don’t you be like those American kids. So spoiled. Wasteful. Designer clothes and doing drugs and bad things. I take care of them all the time. They show no respect for their parents. They run the house.

“Mama—”

“Jaya!” Her mother was using the Keep Your Voice Down, This Is Not Your House and Where Did You Learn to Talk That Way voice.

“About the dress?”

“Next year you get your work permit and you can have a job and buy yourself dresses and whatnot. Jolene from church told me her daughter got a good job at the Home Depot.”

Oh, great. Jaya imagined herself wearing an orange apron and standing around giving advice on garden shears to all the dads in Meadowbrook. Was there nowhere she could hide who she was? Did everyone have to know how much they needed money? Why couldn’t she just be casual, like all those other kids, who sauntered into the cafeteria with a new pair of hundred-twenty-dollar sneakers, as if it were nothing?

“And what about your homework?”

Jaya’s face burned.

“Is that a drawing?” She pointed to a quick sketch Jaya had started with her markers. Mrs. Lal didn’t approve of Jaya’s artwork, even if Jaya’s father had been an artist. Keep your eye on your science, she would often say. That’s what will get you a job.

“Now go and see if there’s anything that Mrs. Harmon needs.”

“Yeah, sure.”

Shoving the flyer into her bag, she thought about the dance again, how all the kids got to dress up and spin across the polished parquet floor under a ceiling of balloons, the golf course lit up just for them. It reminded her of her father: how back in Trinidad, they would wake up early and go to the tourist part of town.

Before Jaya opened the front door, she paused in the hall, looking over to the living room, where Mrs. Lal was now tidying. She felt a whiff of sadness watching her mother punch the sofa pillows, just a little too hard.

Sundays in Port of Spain, while her mother studied her nursing books, Jaya used to accompany her father to the beach, where he would set up his easel by one of the resorts and paint, and sometimes sell his work to the tourists. She would lean against his legs, digging her toes into the hot white sand, watching the foamy surf curl and break on the shore. Not far away was an octagonal restaurant, where she could hear the tap-tap melody of a steel band, men and women dancing under Chinese lanterns that shivered in the breeze.

Then her father began to complain of stomach troubles and went into the hospital for tests. As he grew sicker, his hands trembled and he could barely hold up the brush; he still lugged his easel to the beach, but it became harder for him to work for long stretches. His figures became more ghostly, as if he didn’t have the energy to fill them in. At the end, he would lie in bed with a board propped across his knees and try to draw, but most of the time he fell asleep before he was done.

After Jaya’s father died, her mother began to say, Your parents, Jaya, we’re unfinished business. That’s because she never completed nursing school and her father never finished engineering school—or his life.

Whenever her mother said those words, Jaya felt she was the unfinished one, like one of her father’s drawings, with its spindly lines, all that unfilled space. By the time her father passed away, she was nothing, just pure air and sadness.

Mrs. Harmon was standing next to a garden bed, two sacks of new planting soil slumped on the top step of the porch. “Oh, there you are!” she called. “You think you can help me with this?” She held up a lattice basket filled with drooping black-eyed Susans. “I’m getting an early start.”

“Sure,” Jaya answered.

Usually, on the good-weather days like today, Mrs. Harmon was bent over her flower beds, dressed in her usual khakis and a worn work shirt, a straw hat with a beaded string tied around her chin.

Crouching down, Jaya helped Mrs. Harmon dig a hole, plant the flowers, and sprinkle mulch on top. Jaya noticed—not for the first time—how much Mrs. Harmon’s hands trembled and her eyes watered.

“Why so glum?” Mrs. Harmon asked.

Jaya shrugged. “My mother won’t buy me a dress for the school dance.” She added, “She never buys me anything I want. No new art supplies. Not even a set of markers.”

Mrs. Harmon laughed. “What a dictator.”

Jaya pushed her trowel hard into the ground. “It isn’t fair. She’s always bossing me around.”

“That’s what mothers do. Although in my case, it was my husband who did the bossing.” Mrs. Harmon didn’t have any children of her own.

“Yeah. Well. She does it too much.” Jaya lifted a black-eyed Susan from the basket. She was surprised by the bitter rush of tears in her eyes.

“She is trying to do what’s best for you.”

Best for you. Jaya hated that phrase. “Yeah, but why does she have to bug me so much?” Even saying the words aloud sounded funny, like the American kids at school.

“You’re right. She’s a real monster.” She pointed at Jaya’s hole. “Watch. You need to fill that in more.”

Then she went back to planting, carefully scooping out holes, untangling a stalk from the bunch, patting the dirt smooth.

When Mrs. Harmon stood, she lost her balance, her fingers groping the air like claws. Jaya steadied her, shocked at how thin Mrs. Harmon’s arm was, how she could feel the bone through her skin.

“Oh, dear,” Mrs. Harmon said, sighing. “That’s been happening a bit too much lately.” Jaya noticed that her words came out a little slow and slurred. She also looked odd. Her straw hat had toppled off and hung by its string down her back. Her white hair was snared into a wild nest. And she looked especially puzzled. “Where are my gloves?” she asked.

Jaya pointed. “You’re wearing them.”

Mrs. Harmon gave her a hollow look and staggered up the path.

Recently Jaya and her mother had noticed that Mrs. Harmon had become more absentminded. “A little soft in the head” was the way Mrs. Lal put it. Mrs. Harmon would forget her keys, the route to the supermarket. Jaya’s mother had taken to brewing tea with licorice and ginger, the way she did in Trinidad when old folks started losing their memory.

As Mrs. Harmon headed back to the house, Jaya thought about what her mother always said: If it weren’t for that lady, we wouldn’t even be here in the first place.

Jaya’s mother was a practical woman. When Mrs. Lal and Jaya first came to the United States from Port of Spain, she quickly assessed her options. Nursing school was too expensive. So they’d lived in a tiny apartment in Newark with three dead-bolt locks, while Mrs. Lal signed up with a home aide agency, putting aside fifty dollars a week to send to Jaya’s grandmother back in Trinidad.

One day Mrs. Lal picked Jaya up from school and put them on a New Jersey Transit train that went to a town with a sweet all-American name. It was the most impulsive thing she had ever done, for Mrs. Lal was not an impulsive woman.

To Jaya, Meadowbrook looked like a different country: pretty shingle houses with porches and neatly tended walks and gardens. In the parks they saw lots of West Indian women pushing the strollers or wiping juice spills. Sure enough, Mrs. Lal went to the community bulletin board at the library, where they met a tiny woman with silver hair wearing thick rubber boots, peering at the notices.

“Are you looking for work?” the old woman asked.

“Are you looking for someone?” Mrs. Lal asked back.

Mrs. Harmon didn’t have a lot of money to pay, but her needs were simple: a small laundry load and someone to empty the refrigerator and make sure the house was tolerably clean.

Something about her appealed to Mrs. Lal. She reminded her of the old people in Trinidad. She was thrifty and spare. She saved plastic bags, kept old yogurt containers stacked in the larder. She used a woodstove in the living room, and if it got too cold, she put rolled-up towels against the door cracks. Inside her rooms were Windsor chairs with the polish rubbed off their arms, and all kinds of funny antiques: porcelain-head dolls slumped in a small wicker rocking chair, even a framed embroidery sampler done by some great-great-aunt during the Civil War.

“A real American,” Mrs. Lal teased. “Blue blood, with all those old things.”

“Nonsense,” Mrs. Harmon replied, waving her hand. “Pack rat, more like.”

Soon after Jaya’s mother began working for Mrs. Harmon twice a week, word got around that Mrs. Lal was a good bet. She did three days babysitting for the Siler twins, a Saturday morning cleaning job for the Meisners, and a few others too.

But it was Mrs. Harmon’s place that felt most like home. Jaya would come upon her mother and Mrs. Harmon sitting in the kitchen, swapping recipes and chatting. When Mrs. Harmon had indigestion, Mrs. Lal would bring her stalks of aloe from the Caribbean market that she boiled in an old pot. “You are a dear,” the old woman would say gratefully. Jaya would sit down too, the three of them blowing on their tea mugs and laughing. It was the closest she had come to belonging since they’d come here.

“It’s a sign,” Jaya’s mother liked to say of that day they’d run into Mrs. Harmon, her eyes shining. “We were meant to be here.”

Ten minutes later Mrs. Harmon was back again, only this time she was agitated. “I don’t understand it. I can’t find them.”

“Your gloves?”

She stared at Jaya. “Is that what I was looking for?” She rubbed her eyes, blinking.

Jaya had always been impressed with Mrs. Harmon’s eyes. They were an astoundingly bright blue, the color of the Caribbean, and big. It wasn’t hard to see the little girl that Jaya had seen in the old grainy photographs that were staggered up the wall along Mrs. Harmon’s stairs—the wispy white-blond hair, the girl in a starched pinafore standing next to an old-fashioned wheelbarrow.

“I think so.”

“I’m just not sure.” Mrs. Harmon touched her temple lightly. “There are these spots in my head.”

She went off again, her gait a little more crooked. Inside the house, Jaya heard a loud metallic crash.

Throwing down her spade, Jaya raced through the garden and into the kitchen, where she found Mrs. Harmon leaning against the table. Something was weird: Mrs. Harmon’s face drooped, as if the skin on her cheek were made of putty sliding off her jawbone. Her lips moved thickly around her words. She tried blowing out a few sounds, but it was like a children’s noisy toy, the battery wearing down.

“Oh—” Mrs. Harmon drawled. The next words were more of a gargling noise.

She touched her mouth and practiced a few more sentences. But some circuit had come disconnected, as if her brain couldn’t tell her mouth what to do. “Call …” she struggled out. “… mother.” That seemed to knock the breath out of her.

Jaya rushed upstairs to the bedroom, where she found her mother looping the vacuum hose onto its hook, and pulled her down the stairs.

Jaya was amazed at her mother’s efficiency, all the little important things she knew. How she led Mrs. Harmon by the wrist, even as her right foot was dragging on the floor, and laid her gently on the sofa. How she checked her pulse, probed her lids.

“Don’t panic. Just lie right there. I believe you’re having a stroke. But you’re going to be all right, darlin’.”

Mrs. Harmon nodded, her blue eyes wide and frightened.

Then Mrs. Lal hurried into the kitchen, called 911, and very firmly gave them the instructions. “Vitals okay. Her heart is racing a little. But she needs an ambulance right away.”

Jaya stood a few feet away, unable to keep her eyes off Mrs. Harmon’s arm, which hung, limp, off the sofa edge.

“Jaya!”

Jaya could not move. Her insides felt like crumbling chalk, trickling through the soles of her feet.

Her mother came to her, putting a firm hand on each shoulder. “I need you now. No spacing out. I’ll go to the hospital, but you need to stay here and close up the house. Do you hear me?”

Jaya trembled. Mrs. Harmon’s body was very still now.

“Jaya!”

Jaya reeled back, as if struck. She knew she couldn’t be as calm and brave as her mother wanted her to be. She could hear her mother telling her sternly, Jaya, we don’t have time to be cowards in this life. Not the life that was handed to us, a widow mother and a daughter. We got to be strong.

After a few minutes an ambulance came shrieking up the driveway, its red lights cascading across the walls. Jaya could hear the scratchy whine of a walkie-talkie, a metallic thump as a stretcher was lowered down. The sound shook right through her.

An instant later the front door banged shut and the ambulance was gone, its siren piercing the air.

Call your friends, Jaya told herself. But she couldn’t move. She could only stand on the bare floorboards, listening to wind scour the windowpanes.

© 2010 Marina Budhos

Meadowbrook, New Jersey, looks like it’s right out of an old-time postcard. It has a big town hall, with huge columns and a neat border of red tulips. There’s a quaint little Main Street, its wrought-iron lampposts twined with evergreen sprigs at Christmas; a big green park, where the kids trace ice-skating loops on the frozen pond.

The town is nestled in a valley, and on one side is a steep incline that thrusts up into the ravine, where some of the expensive modern houses are perched like wood and glass boxes. On the other side the larger homes slowly give way to two-family houses and apartments on gritty Haley Avenue and to the big box stores of Route 12. More and more, shiny new condos have sprung up in the open gaps of land, a grove of pale brick McMansions standing where an old horse stable used to be.

Halfway up the hill, in the old section of town, is Mrs. Abigail Harmon’s house. It isn’t much of a house, as far as Meadowbrook houses go. More it’s a cottage, with a steep gabled roof and low exposed beams. The garden is a froth of eccentric tastes: pinwheels and tangled raspberry bushes, a crumbling slate wall and herb garden with chipped zigzagging paths. Mrs. Harmon inherited the place from her mother, who’d been born in the pink-wallpaper nursery, and whose grandfather once owned the hundred acres of farmland that makes up what is Meadowbrook today.

Around the time Mrs. Harmon was born, her family’s apple orchard was sold off to build the train station. Nowadays, when the early train draws up, a stream of women, mostly from the Caribbean or Latin America, step down in their rubber-soled shoes, cradling their Dunkin’ Donuts coffees, and make their way to the pretty clapboard houses. A few minutes later, up and down the streets, comes a chiming of voices, good-byes, slammed doors, cars backing down driveways, mothers and fathers rushing across town with their briefcases and still-wet hair to catch the next train to the city.

It was one of those not-quite-spring days, weak sun slanting through the drafty windows, and Mrs. Lal, the housekeeper at Mrs. Harmon’s place, was giving the vacuum one last firm push on the bedroom floor. Mrs. Lal stood tall at nearly six feet, black hair cropped short and stylish, showing her broad neck and shoulders. Mothers liked her because she gave them a tidy sense of everything in its place: children in bed by seven o’clock, no whining, no peas left behind on the plates.

Downstairs, Mrs. Lal’s daughter, Jaya, was sitting at the big table in the kitchen. She was supposed to be memorizing the periodic table. Really she was trying to work up the nerve to tell her mother about the middle school spring dance.

“Jaya!”

Jaya’s mother stood in the kitchen doorway, holding up three colored markers. “Jaya Lal, you have something against putting the tops on things?”

“Sorry.”

“How many times I have to tell you? This isn’t your house. You can’t just go mooning around like it’s yours. What’s Mrs. Harmon going to think of the way I’m raising you!”

“Okay, okay.”

In fact, what Jaya liked about Mrs. Harmon’s house was that she could treat it like hers. She didn’t have to say hello. Or good-bye. Mrs. Harmon just assumed she’d walk in if she felt like it. Of all her mother’s bosses, Mrs. Harmon was the only one who seemed to want Jaya there—she encouraged it. Make yourself at home. I’ve got too many rooms as it is. Jaya would spread out her homework at the nicked pine table or help herself to what was in the refrigerator, even though half the time the milk was well past its expiration date.

As Mrs. Lal was turning away, Jaya called out softly, “Mama?”

“Yes?”

Jaya hesitated. Shoved into her backpack was a bright pink flyer saying SPRING DANCE EXTRAVAGANZA! Quietly she handed the sheet to her mother, watching Mrs. Lal’s brow furrow while she read it. Usually Jaya didn’t bother showing her mother any of the permission slips for ski trips or overnights to Washington, D.C. She just threw them into the garbage. Even if there was some kind of disclaimer in tiny print at the bottom that the school would pay for those “in need.” No way was she going to sign up for that.

“It’s a really big deal.” Her voice quivered. “Me and my friends, we wanted to go.”

Her mother’s mouth made a tight line.

“And … I thought maybe I could get a new dress?”

“What’s wrong with that blue dress you bought last year?”

“That was last year.”

Silence fell as her mother kept standing in the doorway, the flyer clutched in her hand. Jaya could hear her mother go on: Don’t you be like those American kids. So spoiled. Wasteful. Designer clothes and doing drugs and bad things. I take care of them all the time. They show no respect for their parents. They run the house.

“Mama—”

“Jaya!” Her mother was using the Keep Your Voice Down, This Is Not Your House and Where Did You Learn to Talk That Way voice.

“About the dress?”

“Next year you get your work permit and you can have a job and buy yourself dresses and whatnot. Jolene from church told me her daughter got a good job at the Home Depot.”

Oh, great. Jaya imagined herself wearing an orange apron and standing around giving advice on garden shears to all the dads in Meadowbrook. Was there nowhere she could hide who she was? Did everyone have to know how much they needed money? Why couldn’t she just be casual, like all those other kids, who sauntered into the cafeteria with a new pair of hundred-twenty-dollar sneakers, as if it were nothing?

“And what about your homework?”

Jaya’s face burned.

“Is that a drawing?” She pointed to a quick sketch Jaya had started with her markers. Mrs. Lal didn’t approve of Jaya’s artwork, even if Jaya’s father had been an artist. Keep your eye on your science, she would often say. That’s what will get you a job.

“Now go and see if there’s anything that Mrs. Harmon needs.”

“Yeah, sure.”

Shoving the flyer into her bag, she thought about the dance again, how all the kids got to dress up and spin across the polished parquet floor under a ceiling of balloons, the golf course lit up just for them. It reminded her of her father: how back in Trinidad, they would wake up early and go to the tourist part of town.

Before Jaya opened the front door, she paused in the hall, looking over to the living room, where Mrs. Lal was now tidying. She felt a whiff of sadness watching her mother punch the sofa pillows, just a little too hard.

Sundays in Port of Spain, while her mother studied her nursing books, Jaya used to accompany her father to the beach, where he would set up his easel by one of the resorts and paint, and sometimes sell his work to the tourists. She would lean against his legs, digging her toes into the hot white sand, watching the foamy surf curl and break on the shore. Not far away was an octagonal restaurant, where she could hear the tap-tap melody of a steel band, men and women dancing under Chinese lanterns that shivered in the breeze.

Then her father began to complain of stomach troubles and went into the hospital for tests. As he grew sicker, his hands trembled and he could barely hold up the brush; he still lugged his easel to the beach, but it became harder for him to work for long stretches. His figures became more ghostly, as if he didn’t have the energy to fill them in. At the end, he would lie in bed with a board propped across his knees and try to draw, but most of the time he fell asleep before he was done.

After Jaya’s father died, her mother began to say, Your parents, Jaya, we’re unfinished business. That’s because she never completed nursing school and her father never finished engineering school—or his life.

Whenever her mother said those words, Jaya felt she was the unfinished one, like one of her father’s drawings, with its spindly lines, all that unfilled space. By the time her father passed away, she was nothing, just pure air and sadness.

Mrs. Harmon was standing next to a garden bed, two sacks of new planting soil slumped on the top step of the porch. “Oh, there you are!” she called. “You think you can help me with this?” She held up a lattice basket filled with drooping black-eyed Susans. “I’m getting an early start.”

“Sure,” Jaya answered.

Usually, on the good-weather days like today, Mrs. Harmon was bent over her flower beds, dressed in her usual khakis and a worn work shirt, a straw hat with a beaded string tied around her chin.

Crouching down, Jaya helped Mrs. Harmon dig a hole, plant the flowers, and sprinkle mulch on top. Jaya noticed—not for the first time—how much Mrs. Harmon’s hands trembled and her eyes watered.

“Why so glum?” Mrs. Harmon asked.

Jaya shrugged. “My mother won’t buy me a dress for the school dance.” She added, “She never buys me anything I want. No new art supplies. Not even a set of markers.”

Mrs. Harmon laughed. “What a dictator.”

Jaya pushed her trowel hard into the ground. “It isn’t fair. She’s always bossing me around.”

“That’s what mothers do. Although in my case, it was my husband who did the bossing.” Mrs. Harmon didn’t have any children of her own.

“Yeah. Well. She does it too much.” Jaya lifted a black-eyed Susan from the basket. She was surprised by the bitter rush of tears in her eyes.

“She is trying to do what’s best for you.”

Best for you. Jaya hated that phrase. “Yeah, but why does she have to bug me so much?” Even saying the words aloud sounded funny, like the American kids at school.

“You’re right. She’s a real monster.” She pointed at Jaya’s hole. “Watch. You need to fill that in more.”

Then she went back to planting, carefully scooping out holes, untangling a stalk from the bunch, patting the dirt smooth.

When Mrs. Harmon stood, she lost her balance, her fingers groping the air like claws. Jaya steadied her, shocked at how thin Mrs. Harmon’s arm was, how she could feel the bone through her skin.

“Oh, dear,” Mrs. Harmon said, sighing. “That’s been happening a bit too much lately.” Jaya noticed that her words came out a little slow and slurred. She also looked odd. Her straw hat had toppled off and hung by its string down her back. Her white hair was snared into a wild nest. And she looked especially puzzled. “Where are my gloves?” she asked.

Jaya pointed. “You’re wearing them.”

Mrs. Harmon gave her a hollow look and staggered up the path.

Recently Jaya and her mother had noticed that Mrs. Harmon had become more absentminded. “A little soft in the head” was the way Mrs. Lal put it. Mrs. Harmon would forget her keys, the route to the supermarket. Jaya’s mother had taken to brewing tea with licorice and ginger, the way she did in Trinidad when old folks started losing their memory.

As Mrs. Harmon headed back to the house, Jaya thought about what her mother always said: If it weren’t for that lady, we wouldn’t even be here in the first place.

Jaya’s mother was a practical woman. When Mrs. Lal and Jaya first came to the United States from Port of Spain, she quickly assessed her options. Nursing school was too expensive. So they’d lived in a tiny apartment in Newark with three dead-bolt locks, while Mrs. Lal signed up with a home aide agency, putting aside fifty dollars a week to send to Jaya’s grandmother back in Trinidad.

One day Mrs. Lal picked Jaya up from school and put them on a New Jersey Transit train that went to a town with a sweet all-American name. It was the most impulsive thing she had ever done, for Mrs. Lal was not an impulsive woman.

To Jaya, Meadowbrook looked like a different country: pretty shingle houses with porches and neatly tended walks and gardens. In the parks they saw lots of West Indian women pushing the strollers or wiping juice spills. Sure enough, Mrs. Lal went to the community bulletin board at the library, where they met a tiny woman with silver hair wearing thick rubber boots, peering at the notices.

“Are you looking for work?” the old woman asked.

“Are you looking for someone?” Mrs. Lal asked back.

Mrs. Harmon didn’t have a lot of money to pay, but her needs were simple: a small laundry load and someone to empty the refrigerator and make sure the house was tolerably clean.

Something about her appealed to Mrs. Lal. She reminded her of the old people in Trinidad. She was thrifty and spare. She saved plastic bags, kept old yogurt containers stacked in the larder. She used a woodstove in the living room, and if it got too cold, she put rolled-up towels against the door cracks. Inside her rooms were Windsor chairs with the polish rubbed off their arms, and all kinds of funny antiques: porcelain-head dolls slumped in a small wicker rocking chair, even a framed embroidery sampler done by some great-great-aunt during the Civil War.

“A real American,” Mrs. Lal teased. “Blue blood, with all those old things.”

“Nonsense,” Mrs. Harmon replied, waving her hand. “Pack rat, more like.”

Soon after Jaya’s mother began working for Mrs. Harmon twice a week, word got around that Mrs. Lal was a good bet. She did three days babysitting for the Siler twins, a Saturday morning cleaning job for the Meisners, and a few others too.

But it was Mrs. Harmon’s place that felt most like home. Jaya would come upon her mother and Mrs. Harmon sitting in the kitchen, swapping recipes and chatting. When Mrs. Harmon had indigestion, Mrs. Lal would bring her stalks of aloe from the Caribbean market that she boiled in an old pot. “You are a dear,” the old woman would say gratefully. Jaya would sit down too, the three of them blowing on their tea mugs and laughing. It was the closest she had come to belonging since they’d come here.

“It’s a sign,” Jaya’s mother liked to say of that day they’d run into Mrs. Harmon, her eyes shining. “We were meant to be here.”

Ten minutes later Mrs. Harmon was back again, only this time she was agitated. “I don’t understand it. I can’t find them.”

“Your gloves?”

She stared at Jaya. “Is that what I was looking for?” She rubbed her eyes, blinking.

Jaya had always been impressed with Mrs. Harmon’s eyes. They were an astoundingly bright blue, the color of the Caribbean, and big. It wasn’t hard to see the little girl that Jaya had seen in the old grainy photographs that were staggered up the wall along Mrs. Harmon’s stairs—the wispy white-blond hair, the girl in a starched pinafore standing next to an old-fashioned wheelbarrow.

“I think so.”

“I’m just not sure.” Mrs. Harmon touched her temple lightly. “There are these spots in my head.”

She went off again, her gait a little more crooked. Inside the house, Jaya heard a loud metallic crash.

Throwing down her spade, Jaya raced through the garden and into the kitchen, where she found Mrs. Harmon leaning against the table. Something was weird: Mrs. Harmon’s face drooped, as if the skin on her cheek were made of putty sliding off her jawbone. Her lips moved thickly around her words. She tried blowing out a few sounds, but it was like a children’s noisy toy, the battery wearing down.

“Oh—” Mrs. Harmon drawled. The next words were more of a gargling noise.

She touched her mouth and practiced a few more sentences. But some circuit had come disconnected, as if her brain couldn’t tell her mouth what to do. “Call …” she struggled out. “… mother.” That seemed to knock the breath out of her.

Jaya rushed upstairs to the bedroom, where she found her mother looping the vacuum hose onto its hook, and pulled her down the stairs.

Jaya was amazed at her mother’s efficiency, all the little important things she knew. How she led Mrs. Harmon by the wrist, even as her right foot was dragging on the floor, and laid her gently on the sofa. How she checked her pulse, probed her lids.

“Don’t panic. Just lie right there. I believe you’re having a stroke. But you’re going to be all right, darlin’.”

Mrs. Harmon nodded, her blue eyes wide and frightened.

Then Mrs. Lal hurried into the kitchen, called 911, and very firmly gave them the instructions. “Vitals okay. Her heart is racing a little. But she needs an ambulance right away.”

Jaya stood a few feet away, unable to keep her eyes off Mrs. Harmon’s arm, which hung, limp, off the sofa edge.

“Jaya!”

Jaya could not move. Her insides felt like crumbling chalk, trickling through the soles of her feet.

Her mother came to her, putting a firm hand on each shoulder. “I need you now. No spacing out. I’ll go to the hospital, but you need to stay here and close up the house. Do you hear me?”

Jaya trembled. Mrs. Harmon’s body was very still now.

“Jaya!”

Jaya reeled back, as if struck. She knew she couldn’t be as calm and brave as her mother wanted her to be. She could hear her mother telling her sternly, Jaya, we don’t have time to be cowards in this life. Not the life that was handed to us, a widow mother and a daughter. We got to be strong.

After a few minutes an ambulance came shrieking up the driveway, its red lights cascading across the walls. Jaya could hear the scratchy whine of a walkie-talkie, a metallic thump as a stretcher was lowered down. The sound shook right through her.

An instant later the front door banged shut and the ambulance was gone, its siren piercing the air.

Call your friends, Jaya told herself. But she couldn’t move. She could only stand on the bare floorboards, listening to wind scour the windowpanes.

© 2010 Marina Budhos

Product Details

- Publisher: Atheneum Books for Young Readers (May 3, 2011)

- Length: 320 pages

- ISBN13: 9781442421288

- Grades: 7 and up

- Ages: 12 - 99

Browse Related Books

Awards and Honors

- ALA Popular Paperbacks for Young Adults - Top Ten

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Tell Us We're Home Trade Paperback 9781442421288

- Author Photo (jpg): Marina Budhos Photograph courtesy of the author(0.7 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit