Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

Table of Contents

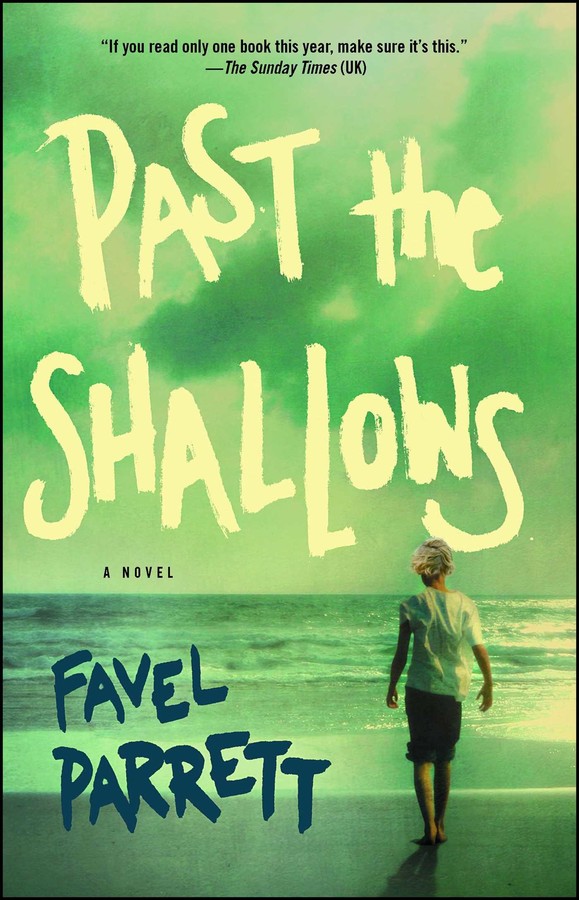

About The Book

Joe, Miles, and Harry are growing up on the remote southern coast of Tasmania—a stark, untamed landscape swathed by crystal blue waters. The rhythm of their days is dictated by the natural world, and by their father’s moods. Like the ocean he battles daily to make a living as a fisherman, he is wild and volatile—a hard drinker warped by a devastating secret. Unlike Joe, Harry and Miles are too young to move out, and so they attempt to stay as invisible as possible whenever their father is home. Miles tries his best to watch out for Harry, but he can’t be there all the time. Often alone, Harry finds joy in the small treasures he discovers by the edge of the sea—shark eggs, cuttlefish bones, and the friendship of a mysterious neighbor. But sometimes small treasures, or a brother’s love, simply are not enough…

Excerpt

Harry stood on the sand and looked down the wide, curved beach of Cloudy Bay. Everything was clean and golden and crisp, the sky almost violet with the winter light, and he wished that he wasn’t afraid. They were leaving him again, his brothers, Miles already half in his wet suit and Joe standing tall, eyes lost to the water.

Water that was always there. Always everywhere. The sound and the smell and the cold waves making Harry different. And it wasn’t just because he was the youngest. He knew the way he felt about the ocean would never leave him now. It would be there always, right inside him.

That was just how it was.

“What should I find?” he asked.

Joe shook his dry wet suit out hard. “Um . . . A cuttlefish bone, a nice bit of driftwood . . .”

“A shark egg,” Miles said.

And there was silence.

Harry waited for Miles to say he was joking, waited for him to say something, but he didn’t. He just kept waxing his board.

So Harry stood up and ran.

He followed the marks of high tide left behind on the sand and his eyes skimmed the pebbles, the shiny jelly sacks, the broken shells. Cuttlefish were easy but shark eggs were impossible. They looked just like seaweed. He kept thinking he’d found one only to realize it was just a bit of kelp or a grimy pebble. There was hardly any point in trying. But he did try. He always found everything on the list. Always.

There was a cormorant gliding low, its soft white stomach almost touching the water, and Harry watched it as it moved. He watched it slow down and land on a rock on the shore. He walked close, walked right up to the rock, but the bird didn’t move. It just stayed still. And he’d never seen one alone. Not like this, on the land. They were always in groups, cormorants. Huddled together in groups on the cliffs and rocks, long necks reaching up to the sun. Sometimes they stayed like that all day. Together. Waiting and watching. Resting.

The bird called softly, and Harry was so close that he felt the sound vibrate inside him. He wanted to reach out and touch it, to stroke the silky shimmering feathers down the cormorant’s back. But he stayed still, kept his arms by his sides. He thought that maybe the cormorant was sick. That maybe it couldn’t find the others. And he didn’t know how they made it, how they survived. Flying over all that ocean, flying and flying in the wind and in the rain. Diving into the cold water.

They washed up in the surf sometimes, the lost ones.

The bird called again. It bobbed its head up and down and spread its wings, then it was gone.

Harry left the beach and ventured into the dunes. Might find a good bit of driftwood in there or something interesting at least. He ran up and down the small humps and valleys, the loose sand getting firmer under his feet, and he kept on going. He could hardly see the beach anymore. It was farther than he had ever been. He slowed down, started walking. He looked ahead. There was some kind of clearing, small trees all around. Shrubs. It was a good sheltered place; the wind wouldn’t get in this far even if it was really blowing. You could camp here. You could stay here and it would be all right.

Behind a shrub, a pile of shells. A giant pile—old and brittle and white from the sun. Oyster and mussel, pipi and clam, the armor of a giant crab. Harry picked up an abalone shell, the edges loose and dusty in his hands. And every cell in his body stopped. Felt it. This place. Felt the people who had been here before, breathing and standing alive where he stood. People who were long dead now. Long gone. And Harry understood, right down in his guts, that time ran on forever and that one day he would die.

The skin on his hands tingled and pricked.

He dropped the shell and ran.

He had to wait for ages but finally Joe came in. Miles stayed out. He was way out deep and it didn’t even look like there were any waves out there. He was just sitting in the water. Just sitting there and Harry was starving, couldn’t stop thinking about those sandwiches. The cheese and chutney ones.

“I didn’t find it. The shark egg.”

Joe was struggling with his wet suit, getting his arms free, and he was twisting and panting, not looking at Harry. “Maybe next time,” he said, but Harry didn’t think it was likely.

When Joe was finally back in his clothes he started unpacking the stuff from the dinghy, the thermos and the tin cups and the rug and the sandwiches. As long as they didn’t have to wait for Miles—no, Harry wouldn’t be able to wait for Miles even if Joe said he had to because Miles could stay out in the water forever, even if it was freezing, and Harry just had to have one of the sandwiches now.

“This place is old,” he said, his mouth full of bread.

Joe made a sound but he wasn’t really listening. He was somewhere else, maybe still out there in the water with Miles. But it didn’t matter.

This place was old. Harry knew it.

As old as the world.

Past the Shallows

Miles got in the dinghy with the men, with Martin and Jeff and Dad, and he didn’t speak. No one spoke on the way out to the boat. He hadn’t been able to eat his toast at home in the early darkness, and now just at dawn he wished he had.

His stomach was empty, this first day.

First day of school holidays. First day he must man the boat alone while the men go down. Old enough now, he must take his place. Just like his brother before him, he must fill the gap Uncle Nick left.

Because the bank owned the boat now. Because the bank owned everything.

The boat chugged and rattled its way through the heads, and Miles felt the channel grab hold, pull on her hard. She was weak, the Lady Ida, she seemed old now, and the crossing was slow. She plowed through the deepest part of the channel leaving a wide wake of ridges behind, and Miles knew this was where it would have happened. Where Uncle Nick would have been dragged out alone in the dark where the rip ran strongest.

And they never found him.

Not one bit.

Not his boots.

Not his bones.

Just the dinghy floating loose, empty and washed clean.

Nobody talked about it now, but back then Dad talked about it. He said Uncle Nick must have gone out to check the mooring. He said he’d never forgive himself.

The boat was almost new, anchored out at the mouth of the bay because the swell was right up—a big winter swell, and all the boats were out there. But Nick wouldn’t leave it alone. He wouldn’t stop worrying about the boat. Dad said he went on and on about it at the pub and in the end Dad told him to go and check the damn thing. To go and check it or just shut up about it.

And Miles knew exactly how dark it was that night, the sky blacked out by cloud so thick that nothing came through—no stars or moon or anything. Uncle Nick wouldn’t have been able to see the dinghy or the land or even his own hand in front of his face.

And everyone forgot about him out there because that was the night of the crash.

That was the night when everything changed.

Martin touched his shoulder, stood close.

“It’ll be all right,” he said.

Dad and Jeff were in the cabin and Jeff was staring at him again so Miles looked away. He slipped his yellow windbreaker over his sweater. Dad didn’t have any small enough for him, so he had to wear a man’s size and it was baggy, hung way down past his hands. It was almost better not to wear one at all. He’d get soaked anyway. The only part of him that would stay warm was his head under the tight wool watch cap that made his scalp itch.

He rolled up the sleeves, he put on his gloves.

Bruny was coming clear in the new light.

Miles watched the surface change color—come to life. And even though they were still out deep, away from land, there were places where the water rose like it was climbing a hill, places where the water was angry. And it wasn’t the back of a wave. It wasn’t a peak in the swell. It was the current surging into rocks that hid below, rocks that you couldn’t see even when the tide was low. And if you didn’t know what the rise in water meant, you would never guess those rocks were there. The Hazards. They were called the Hazards of Bruny.

They were all around here, out deep. Rocks that weren’t attached to land but were big enough on their own to disturb the water—to change its path. And maybe they had been islands once, those rocks. Small islands or maybe even bigger ones before they got worn away. Worn by the water and by the wind and the rain until they were gone from sight. And only the foundations remained, hidden and lost under the sea.

There were things that no one could teach you—things about the water. You just knew them or you didn’t and no one could tell you how to read it. How to feel it.

Miles knew the water. He could feel it. And he knew not to trust it.

Reading Group Guide

Get a FREE ebook by joining our mailing list today! Plus, receive recommendations for your next Book Club read.

Topics & Questions for Discussion

1. Aunty Jean is the only female role model the boys have left. She is at times cruel and then caring toward them. Do you consider her a good person? Do you have any sympathy for her? What references within the text have led you to this opinion?

2. Do you think George Fuller sees Harry as just another puppy to rescue? Or does he genuinely care for Harry? There are a few other works of literature that use an ostracized figure in the community to enhance our understanding of the main characters. Why do you think this can be a useful plot device, and do you think it’s effective here?

3. This is a small community where everyone knows who everyone is, as we can see from Mr. Roberts, George and Mrs. Martin in the store. In light of this, why do you think the boys’ home life is allowed to continue? What is the role of men in this community?

4. There are few female figures in Harry’s and Miles’s lives. Is there any evidence of what they think about women?

5. What would be some of the challenges of living here?

6. How challenging would it be to be a woman in this community?

7. Jeff exhibits increasingly dangerous and bullying behavior: the staring, shooting the shark and risking hitting Miles, forcing Harry to drink. Does he bring about Dad’s worst behavior to his sons? Or do you think Dad allows Jeff free rein to reveal his ugly nature? Do you have any sympathy for Dad? What is the evidence within the text that formed your opinion?

8. “Harry stood there looking at the tooth in his hands, and he looked so young and small, like no time had ever passed by since he was the baby in the room and Joe had told Miles to be nice to him and help Mum out. And Miles had thought he wouldn’t like it. But Harry had a way about him. A way that made you promise to take care of him.” (page 187)

Both Joe and Miles are forced to take on responsibility for their brothers, yet they do it quite differently. Joe moved out with Granddad and left the other two behind with their dad when he was thirteen and then ultimately leaves the two of them supposedly forever. Miles, however, stays on even after he is beaten by his father. Why do you think they approach the responsibility so differently?

9. Miles and Harry share an unbreakable bond. Discuss their different reactions to Joe leaving.

10. Joe is also part of this family unit. Why do you think he is painted as one of the family, but also an outsider? He used to work on the boat, now doesn’t. He moved to live with his grandfather. Why do you think Favel Parrett chose not to include point of view from Joe? What effect does this have on the novel? What do you imagine his story would have been?

11. The water throughout the novel is a metaphor for Dad. Do you agree or not, and what from the text made you think this way? Harry fears the water and Miles both loves and hates it. Is there anything within the book that shows us how this relates to the boys’ relationship with Dad?

12. “There was something coming.

“Miles had felt it in the water. Seen it. Swell coming in steady, the wind right on it, pushing. It was ground swell. Brand new and full of punch—days away from its peak.” (page 175)

How does the Tasmanian landscape speak for the characters’ emotions within the text? Are there other references to nature within the book that you found moving? Discuss.

13. Discuss the significance of the shark tooth necklace.

14. Memory plays a big part in this novel. Discuss the way in which memories are invoked in Past the Shallows and what part they play in the story.

15. The gradual piecing together of Miles’s memories about his mother and the night of the accident have a sense of fantasy or dreamlike state about them. Do you think these events happened chronologically? What makes you think that? Did they reveal events the way you’d imagined? What other possibilities had you anticipated?

16. Why do you think Joe wasn’t in the car?

17. Do you think Harry isn’t Dad’s son, and Miles and Joe are? Is it clear-cut? What references within the text have given you that impression?

18. It’s obviously a point of rage for Dad. Do you have any sympathy for him? How did you feel when you learned through Joe that he’d disappeared and that there would be no direct confrontation or punishment for his acts? Was this a satisfactory ending for you? Why/why not?

19. “Harry’s feet hardly seemed to touch the ground as he followed Jake, and it was easy to run. He ran through the trees, reached out, and he could almost touch Jake’s red fur. George was up ahead. George, waving from the top of the hill.

“And when Harry got there, he could see it all.

“The land just as it had been forever—untouched.” (page 211)

Do you believe this is a utopian afterlife image from Harry after death? Or do you think this is a fragment of unconscious dreaming from Miles? How did you reach this conclusion? Are there any other references within the text that have influenced this idea?

20. Harry and Miles’s story is bookended by the evocative passage: “Out past the shallows, past the sandybottomed bays, comes the dark water—black and cold and roaring. Rolling out the invisible paths . . .” What effect did the imagery and repetition have on you going into the beginning of the story? And on leaving the story?

21. Although very evocative of the Tasmanian coast, do you think that the story transcends borders, and would be just as thought-provoking to a reader in another country?

Product Details

- Publisher: Atria Books (April 22, 2014)

- Length: 272 pages

- ISBN13: 9781476754871

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

"Compulsively readable...the simple, unaffected tone of Parrett's writing makes this a poignant read—but it's the story of how these two emotionally distant brothers help each other that makes the novel so moving."

– Oprah.com

“[A]n understated and beautifully penned story… Parrett’s writing is exquisite in its simplicity and eloquence, and her narrative is heart-rending. This poignant story resonates.”

– Kirkus

"Parrett deservedly received critical claim in Australia for this haunting fiction debut. Her writing is vivid and distinct...Parrett's novel sings with an emotional power that marks her as a writer to watch."

– Library Journal, starred review

"Vibrant and intensely moving, this story about three boys in thrall to their angry father sucked me instantly into its emotional currents. Favel Parrett has created a novel as lovely, mysterious, powerful and entrancing as the capricious ocean around which her characters’ lives revolve."

– Christina Schwarz, #1 New York Times bestselling author of Drowning Ruth

"Parrett's remarkable debut examines the bleak life of a broken family in Tasmania, in spare, unflinching prose."

– Publishers Weekly, starred review

"If you read only one book this year, make sure it's this."

– The Sunday Times (UK)

"A finely crafted literary novel that is genuinely moving and full of heart."

– The Age

"So real, so true—this novel sweeps you away in its tide."

– Robert Drewe, author of The Shark Net

"Wintonesque."

– The Herald Sun (Australia)

"Parrett's debut marks the addition of a strong voice to the chorus of Australian literature."

– The Canberra Times (Australia)

"A work by a new master...Parrett's debut is an uncompromising and memorable tale."

– Sunday Tasmanian (Australia)

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Past the Shallows Trade Paperback 9781476754871

- Author Photo (jpg): Favel Parrett © Erin King(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit