Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

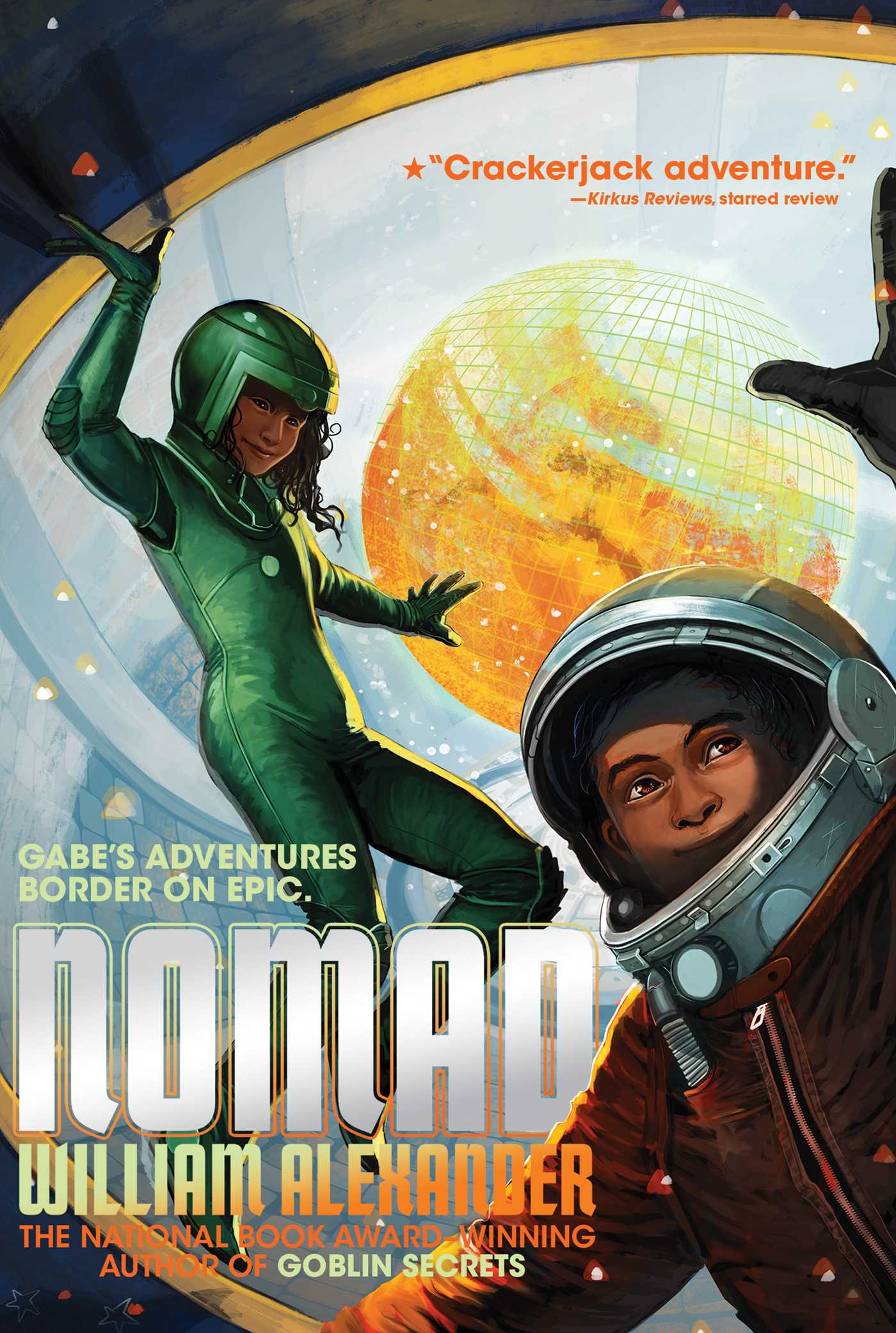

Nomad

LIST PRICE $7.99

PRICE MAY VARY BY RETAILER

Get 30% off hardcovers with code MOM30, plus free shipping on orders of $40 or more. Terms apply.

Buy from Other Retailers

Table of Contents

About The Book

Gabe Fuentes is in a race against time—and aliens—in this intergalactic sequel to Ambassador, which Booklist called “an exciting sci-fi adventure, perceptively exploring what it means to be alien,” from National Book Award winner William Alexander.

When we last left Earth’s Ambassador, Gabe Fuentes, he was stranded on the moon. And when he’s rescued by Kaen, another Ambassador, things don’t get better: It turns out that the Outlast— a race of aliens that has been systematically wiping out all other creatures—are coming. And they’ve set their sights on Earth.

Enter Nadia. She was Earth’s Ambassador before Gabe, but left her post in order to stop the Outlast. Nadia has discovered that the Outlast can conquer worlds by travelling fast through lanes created by the mysterious Machinae. No one has communicated with the Machinae in centuries, but Nadia is determined to try, and Gabe and Kaen want to help her. But the three Ambassadors don’t know that the Outlast have discovered what they are doing, and have sent assassins to track them down.

As Nadia heads deeper into space to find the Machinae, Gabe and Kaen return to Earth, where Gabe is trying to find another type of alien—his father, who was deported to Mexico, and who Gabe is desperate to bring home. From a detention center in the center of the Arizona desert to the Embassy in the center of the galaxy, the three Ambassadors race against time to save their worlds in this exciting, funny, mind-bending adventure.

When we last left Earth’s Ambassador, Gabe Fuentes, he was stranded on the moon. And when he’s rescued by Kaen, another Ambassador, things don’t get better: It turns out that the Outlast— a race of aliens that has been systematically wiping out all other creatures—are coming. And they’ve set their sights on Earth.

Enter Nadia. She was Earth’s Ambassador before Gabe, but left her post in order to stop the Outlast. Nadia has discovered that the Outlast can conquer worlds by travelling fast through lanes created by the mysterious Machinae. No one has communicated with the Machinae in centuries, but Nadia is determined to try, and Gabe and Kaen want to help her. But the three Ambassadors don’t know that the Outlast have discovered what they are doing, and have sent assassins to track them down.

As Nadia heads deeper into space to find the Machinae, Gabe and Kaen return to Earth, where Gabe is trying to find another type of alien—his father, who was deported to Mexico, and who Gabe is desperate to bring home. From a detention center in the center of the Arizona desert to the Embassy in the center of the galaxy, the three Ambassadors race against time to save their worlds in this exciting, funny, mind-bending adventure.

Excerpt

Nomad 1 Zvezda Lunar Base: 1974

Nadia Antonovna Kollontai, the ambassador of her world, was not on her world.

She went walking on the moon. Sunlight bounced off the gray stone around her. She felt intense warmth through her bulky orange suit. The reflected glare blotted out all other stars. It turned the sky into absolute darkness. That felt close and comforting rather than infinite, as though Nadia had hidden both herself and the moon underneath a very thick blanket.

She looked forward to throwing that blanket aside.

“Nadia?” Her radio crackled and sputtered. “Zvezda base to Ambassador Nadia . . .”

“Hello, Envoy,” she said.

“By my count your oxygen is running low.” The Envoy spoke Russian, and sounded exactly like her uncle Konstantine. It had borrowed Uncle’s voice to seem familiar, familial, and comforting. It did sound familiar, but not especially comforting. Uncle Konstantine and Aunt Marina had had many practical virtues between them, but neither one of them had ever learned how to be comforting.

“Probably,” she said, as though she didn’t care how much air she had left. This wasn’t actually true. She had kept careful tabs on her oxygen.

“Please cut short your unnecessary moonwalk and come back inside.”

“On my way,” she said, but she circled back the long way around to give herself more room to run.

Nadia took huge and sailing lunar leaps, gaining speed. She felt like she could push herself clear of the moon entirely if she only kicked hard enough. She felt like she could fly through space as her own ship.

She took several smaller steps to slow down when the Zvezda base came back into view.

Gray-and-beige modules of the station lay half-buried in lunar dirt. The dirt was supposed to protect the modules from radiation and small meteors, and maybe it did protect the half that was actually covered, but the robotic shovel had broken before finishing the job. Now it looked like a ruin, a relic of some ancient space age rather than the cutting, rusting edge of Soviet engineering.

Nadia tried not to be cynical about it. The moon base functioned well enough. She lived there. She breathed and ate there. But Nadia was from Moscow, and asking a Muscovite kid to be anything other than cynical about grand Soviet accomplishments was like asking fish to have eyelids. Besides, Aunt and Uncle had designed most of this place (though only Uncle actually got credit for it), so even though Nadia was proud of their astroengineering, she had also overheard enough dinnertime grumblings about shoddy shortcuts to know that Zvezda barely held itself together with string and spit. And Nadia loved sarcasm. She loved how it could make any word mean both itself and its opposite.

“Nadia?” the Envoy asked, borrowed voice crackling over the radio. She imagined it peering through curved window glass in one of the unburied base modules, craning a long, purple neck to look for her. “Nadia, have you reached the airlock yet?”

“Not yet,” she said, her voice pitched to soothe the worried Envoy. “But I can see it from here. Just a few minutes away.”

“Stop,” the Envoy insisted. “Stop right there. Don’t come any closer. Find something to hide behind.”

Nadia shuffled to a stop and looked around. She stood on a flat, featureless stretch of rock with nothing at all to hide behind. “What’s wrong?”

“The Khelone ship is here. It is landing soon. It is landing immediately. I told you this would be a bad time to go for another idle walk.”

“Fantastic,” she said, and made the word mean both itself and its opposite. “You said it would be here soon as in days, not soon as in minutes.” She was already running, each step a lunar leap.

“Don’t pretend that the word soon is more precise than it really is,” the Envoy told her. “Have you found cover yet?”

“Maybe.” She spotted a small crater, a hole in the face of the moon where some small rock had smacked into it, months or centuries or millions of years ago. She skidded while shifting direction, took two more leaps, reached the crater—and sailed right over it. She had to take several small stutter steps to slow down and double back. Then she hopped into the shallow hole.

Nadia stood still, caught her breath, and finally looked up.

She saw the Khelone ship. It was the only visible thing in the sky besides the sun itself.

“Looks like a barnacle,” she said.

“Apt comparison,” said the Envoy. “Khelone ships are living things. The pitted outer hull is a grown shell. Are you somewhere safe?”

“I think so,” Nadia said. “Mostly. Probably.”

The Envoy made a pbbbbbbt noise of nervous exasperation. “The force of the Khelone landing will throw a wave of dust and stone in all directions. One of those stones might shatter your helmet, or puncture your suit. That would be almost fitting. We survived a harrowing rocket launch, nearly exploded before we left the atmosphere, and barely managed to land out here. You have lived through impossible dangers already. Now you might be killed within sight of safety, by the very ship you summoned here, because you couldn’t resist another unnecessary moonwalk.”

“Can’t bite your own elbow,” Nadia said. It was one of Uncle Konstantine’s expressions, and meant essentially the same thing as “so close and yet so far.” He always said it with a shrug. Uncle had had lots of expressions, as though he were in some sort of hurry to become a folk-wisdom-dispensing old man—which would never happen now. He had lived long enough to become grumpy, but not long enough to be old.

Nadia turned her thoughts around to walk carefully away from memories of Uncle Konstantine and Aunt Marina.

“I have no elbows, Ambassador,” the Envoy said with Uncle’s voice.

She tried to crouch down in the crater. It wasn’t easy. Cosmonaut suits did not lend themselves to crouching. “Say something nice. I might be about to die, and then your scolding complaint about elbows will be the last thing I’ll ever hear. How sad. Say something nicer than that.”

“Keep your head down, Nadia,” the Envoy said. “Please don’t die.”

The Khelone ship threw a burst of energy at the ground to slow itself. That kicked up a wave of dust and stone, which expanded outward from the landing site in silence. Nadia tried to keep her head down, but small stones still smacked into her suit and helmet.

She had very carefully appropriated this suit before coming to the moon. It had once belonged to Valentina Tereshkova, the first female cosmonaut—and, prior to Nadia’s flight, the only female cosmonaut. At that moment Nadia worried more about damaging the space suit of Valentina Tereshkova than she worried about dying from the damage. She idolized Valentina. The cosmonaut had repaired and reengineered her Vostok spacecraft while already in orbit. It never would have landed again otherwise. That was an embarrassing state secret, but Nadia came from a family of rocket engineers so she knew about it anyway.

The small, pelting debris settled down. Nadia didn’t hear any hissing noises from Valentina Tereshkova’s borrowed suit.

“Nadia?” the Envoy asked, worried.

“Still here,” she said.

“Excellent,” said the Envoy. “Now please hurry back. Try to reach the station before our guest does.”

* * * *

Nadia Antonovna Kollontai was born on April 12, 1961. Yuri Gagarin launched into space on the same day. He was the first human to do so—or at least the first to come home again afterward.

In 1969 Nadia became the ambassador of Terra and all Terran life. She was eight years old at the time. Ambassadors are always young. She lived with her aunt and uncle, and she handled intergalactic incidents on behalf of her planet. She did so in secret. Most human ambassadors do.

Meanwhile her aunt Marina and uncle Konstantine worked on the Zvezda base. Americans had just landed on the moon, so lunar goals had fallen out of favor in the Soviet space program. Uncle Konstantine convinced his project leaders to send a few rockets and drop a few modules of moon base by remote control, but the project ended there. Zvezda sat unfinished, unoccupied, and already abandoned.

Then Ambassador Nadia needed an off-planet site to arrange a meeting and hitch a ride.

She stowed away aboard the last N-1 rocket to Zvezda in August 1974. After that she spent more than a month eating cosmonaut food from toothpaste tubes, taking long moonwalks, and waiting for the Khelone ship to arrive.

Up close it still looked like a towering barnacle.

Nadia wondered what it was like to swim through space the way fish swam in water, no barrier between yourself and all the nothing that there ever was. She wondered what it was like to be a living ship. Then she stopped wondering so she could wrestle with the Zvezda airlock latch. It opened on the third try. Nadia climbed through the airlock, sealed both the outer and the inner doors, and then lifted her helmet visor.

The entrance module looked like the body of an airplane without passenger seats. It did not look hospitable or welcoming. It was a mess, an inauspicious place to make first contact. Engineers had no sense of ceremony. The ones in her family didn’t, anyway, and she expected other engineers to be pretty much the same.

The Envoy scootched across the metal floor. It raised up its long neck and puppetlike mouth.

“Ambassador,” it said, borrowed voice dryly formal.

“Envoy,” Nadia answered. “Have you heard anything from our guest?”

“Not yet.”

Nadia nodded. Then she started to pace. She could see the Khelone ship outside, through the module’s single actual window. The opposite side of the module held a video screen pretending to be a window, one that showed looping footage of a scenic mountain view. Someone back home—definitely not Uncle Konstantine, but someone else on his team—believed that artificial scenery would benefit homesick cosmonauts. Nadia didn’t find the fake window beneficial. She tried to ignore it.

“Please stand still,” said the Envoy.

“I’m thinking,” said Nadia.

“Must you always walk while thinking?” the Envoy asked. “Does your brain even work without the kinetic motion of your feet? You’re making me nervous.” It tinkered with a lumpy piece of machinery in its nervousness. “I hope the translator works. I did the best I could, but we have only so much equipment to work with here. Visual information may be distorted.”

“We’ll make do,” said Nadia. “But stop fiddling around. You’re just going to break it.”

She expected the translation device to break anyway. She had expected the rocket that brought them here to explode on the launchpad. She inherited this kind of cheerful hopelessness from Aunt and Uncle—especially from Aunt Marina. “Engineers, rocket scientists, cosmonauts; they all know that things will probably break, fall over, and explode,” her aunt would say. “But they’re always so happy to be wrong.”

Something knocked on the outer hatch of the airlock.

“Poyekhali,” Nadia said. “Here we go.”

Nadia Antonovna Kollontai, the ambassador of her world, was not on her world.

She went walking on the moon. Sunlight bounced off the gray stone around her. She felt intense warmth through her bulky orange suit. The reflected glare blotted out all other stars. It turned the sky into absolute darkness. That felt close and comforting rather than infinite, as though Nadia had hidden both herself and the moon underneath a very thick blanket.

She looked forward to throwing that blanket aside.

“Nadia?” Her radio crackled and sputtered. “Zvezda base to Ambassador Nadia . . .”

“Hello, Envoy,” she said.

“By my count your oxygen is running low.” The Envoy spoke Russian, and sounded exactly like her uncle Konstantine. It had borrowed Uncle’s voice to seem familiar, familial, and comforting. It did sound familiar, but not especially comforting. Uncle Konstantine and Aunt Marina had had many practical virtues between them, but neither one of them had ever learned how to be comforting.

“Probably,” she said, as though she didn’t care how much air she had left. This wasn’t actually true. She had kept careful tabs on her oxygen.

“Please cut short your unnecessary moonwalk and come back inside.”

“On my way,” she said, but she circled back the long way around to give herself more room to run.

Nadia took huge and sailing lunar leaps, gaining speed. She felt like she could push herself clear of the moon entirely if she only kicked hard enough. She felt like she could fly through space as her own ship.

She took several smaller steps to slow down when the Zvezda base came back into view.

Gray-and-beige modules of the station lay half-buried in lunar dirt. The dirt was supposed to protect the modules from radiation and small meteors, and maybe it did protect the half that was actually covered, but the robotic shovel had broken before finishing the job. Now it looked like a ruin, a relic of some ancient space age rather than the cutting, rusting edge of Soviet engineering.

Nadia tried not to be cynical about it. The moon base functioned well enough. She lived there. She breathed and ate there. But Nadia was from Moscow, and asking a Muscovite kid to be anything other than cynical about grand Soviet accomplishments was like asking fish to have eyelids. Besides, Aunt and Uncle had designed most of this place (though only Uncle actually got credit for it), so even though Nadia was proud of their astroengineering, she had also overheard enough dinnertime grumblings about shoddy shortcuts to know that Zvezda barely held itself together with string and spit. And Nadia loved sarcasm. She loved how it could make any word mean both itself and its opposite.

“Nadia?” the Envoy asked, borrowed voice crackling over the radio. She imagined it peering through curved window glass in one of the unburied base modules, craning a long, purple neck to look for her. “Nadia, have you reached the airlock yet?”

“Not yet,” she said, her voice pitched to soothe the worried Envoy. “But I can see it from here. Just a few minutes away.”

“Stop,” the Envoy insisted. “Stop right there. Don’t come any closer. Find something to hide behind.”

Nadia shuffled to a stop and looked around. She stood on a flat, featureless stretch of rock with nothing at all to hide behind. “What’s wrong?”

“The Khelone ship is here. It is landing soon. It is landing immediately. I told you this would be a bad time to go for another idle walk.”

“Fantastic,” she said, and made the word mean both itself and its opposite. “You said it would be here soon as in days, not soon as in minutes.” She was already running, each step a lunar leap.

“Don’t pretend that the word soon is more precise than it really is,” the Envoy told her. “Have you found cover yet?”

“Maybe.” She spotted a small crater, a hole in the face of the moon where some small rock had smacked into it, months or centuries or millions of years ago. She skidded while shifting direction, took two more leaps, reached the crater—and sailed right over it. She had to take several small stutter steps to slow down and double back. Then she hopped into the shallow hole.

Nadia stood still, caught her breath, and finally looked up.

She saw the Khelone ship. It was the only visible thing in the sky besides the sun itself.

“Looks like a barnacle,” she said.

“Apt comparison,” said the Envoy. “Khelone ships are living things. The pitted outer hull is a grown shell. Are you somewhere safe?”

“I think so,” Nadia said. “Mostly. Probably.”

The Envoy made a pbbbbbbt noise of nervous exasperation. “The force of the Khelone landing will throw a wave of dust and stone in all directions. One of those stones might shatter your helmet, or puncture your suit. That would be almost fitting. We survived a harrowing rocket launch, nearly exploded before we left the atmosphere, and barely managed to land out here. You have lived through impossible dangers already. Now you might be killed within sight of safety, by the very ship you summoned here, because you couldn’t resist another unnecessary moonwalk.”

“Can’t bite your own elbow,” Nadia said. It was one of Uncle Konstantine’s expressions, and meant essentially the same thing as “so close and yet so far.” He always said it with a shrug. Uncle had had lots of expressions, as though he were in some sort of hurry to become a folk-wisdom-dispensing old man—which would never happen now. He had lived long enough to become grumpy, but not long enough to be old.

Nadia turned her thoughts around to walk carefully away from memories of Uncle Konstantine and Aunt Marina.

“I have no elbows, Ambassador,” the Envoy said with Uncle’s voice.

She tried to crouch down in the crater. It wasn’t easy. Cosmonaut suits did not lend themselves to crouching. “Say something nice. I might be about to die, and then your scolding complaint about elbows will be the last thing I’ll ever hear. How sad. Say something nicer than that.”

“Keep your head down, Nadia,” the Envoy said. “Please don’t die.”

The Khelone ship threw a burst of energy at the ground to slow itself. That kicked up a wave of dust and stone, which expanded outward from the landing site in silence. Nadia tried to keep her head down, but small stones still smacked into her suit and helmet.

She had very carefully appropriated this suit before coming to the moon. It had once belonged to Valentina Tereshkova, the first female cosmonaut—and, prior to Nadia’s flight, the only female cosmonaut. At that moment Nadia worried more about damaging the space suit of Valentina Tereshkova than she worried about dying from the damage. She idolized Valentina. The cosmonaut had repaired and reengineered her Vostok spacecraft while already in orbit. It never would have landed again otherwise. That was an embarrassing state secret, but Nadia came from a family of rocket engineers so she knew about it anyway.

The small, pelting debris settled down. Nadia didn’t hear any hissing noises from Valentina Tereshkova’s borrowed suit.

“Nadia?” the Envoy asked, worried.

“Still here,” she said.

“Excellent,” said the Envoy. “Now please hurry back. Try to reach the station before our guest does.”

* * * *

Nadia Antonovna Kollontai was born on April 12, 1961. Yuri Gagarin launched into space on the same day. He was the first human to do so—or at least the first to come home again afterward.

In 1969 Nadia became the ambassador of Terra and all Terran life. She was eight years old at the time. Ambassadors are always young. She lived with her aunt and uncle, and she handled intergalactic incidents on behalf of her planet. She did so in secret. Most human ambassadors do.

Meanwhile her aunt Marina and uncle Konstantine worked on the Zvezda base. Americans had just landed on the moon, so lunar goals had fallen out of favor in the Soviet space program. Uncle Konstantine convinced his project leaders to send a few rockets and drop a few modules of moon base by remote control, but the project ended there. Zvezda sat unfinished, unoccupied, and already abandoned.

Then Ambassador Nadia needed an off-planet site to arrange a meeting and hitch a ride.

She stowed away aboard the last N-1 rocket to Zvezda in August 1974. After that she spent more than a month eating cosmonaut food from toothpaste tubes, taking long moonwalks, and waiting for the Khelone ship to arrive.

Up close it still looked like a towering barnacle.

Nadia wondered what it was like to swim through space the way fish swam in water, no barrier between yourself and all the nothing that there ever was. She wondered what it was like to be a living ship. Then she stopped wondering so she could wrestle with the Zvezda airlock latch. It opened on the third try. Nadia climbed through the airlock, sealed both the outer and the inner doors, and then lifted her helmet visor.

The entrance module looked like the body of an airplane without passenger seats. It did not look hospitable or welcoming. It was a mess, an inauspicious place to make first contact. Engineers had no sense of ceremony. The ones in her family didn’t, anyway, and she expected other engineers to be pretty much the same.

The Envoy scootched across the metal floor. It raised up its long neck and puppetlike mouth.

“Ambassador,” it said, borrowed voice dryly formal.

“Envoy,” Nadia answered. “Have you heard anything from our guest?”

“Not yet.”

Nadia nodded. Then she started to pace. She could see the Khelone ship outside, through the module’s single actual window. The opposite side of the module held a video screen pretending to be a window, one that showed looping footage of a scenic mountain view. Someone back home—definitely not Uncle Konstantine, but someone else on his team—believed that artificial scenery would benefit homesick cosmonauts. Nadia didn’t find the fake window beneficial. She tried to ignore it.

“Please stand still,” said the Envoy.

“I’m thinking,” said Nadia.

“Must you always walk while thinking?” the Envoy asked. “Does your brain even work without the kinetic motion of your feet? You’re making me nervous.” It tinkered with a lumpy piece of machinery in its nervousness. “I hope the translator works. I did the best I could, but we have only so much equipment to work with here. Visual information may be distorted.”

“We’ll make do,” said Nadia. “But stop fiddling around. You’re just going to break it.”

She expected the translation device to break anyway. She had expected the rocket that brought them here to explode on the launchpad. She inherited this kind of cheerful hopelessness from Aunt and Uncle—especially from Aunt Marina. “Engineers, rocket scientists, cosmonauts; they all know that things will probably break, fall over, and explode,” her aunt would say. “But they’re always so happy to be wrong.”

Something knocked on the outer hatch of the airlock.

“Poyekhali,” Nadia said. “Here we go.”

Product Details

- Publisher: Margaret K. McElderry Books (September 20, 2016)

- Length: 288 pages

- ISBN13: 9781442497689

- Grades: 3 - 7

- Ages: 8 - 12

- Lexile ® 640L The Lexile reading levels have been certified by the Lexile developer, MetaMetrics®

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

"[A] crackerjack adventure."

– Kirkus Reviews, starred review

"Filled with a Heinleinesque sense of wonder, National Book Award–winner Alexander's depictions of life in space pave the way for unlimited possibilities."

– Publishers Weekly

Awards and Honors

- International Latino Book Award Honorable Mention

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Nomad Trade Paperback 9781442497689

- Author Photo (jpg): William Alexander Photograph by Alice Dodge(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit