Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

LIST PRICE $18.00

Free shipping when you spend $40. Terms apply.

Buy from Other Retailers

Table of Contents

About The Book

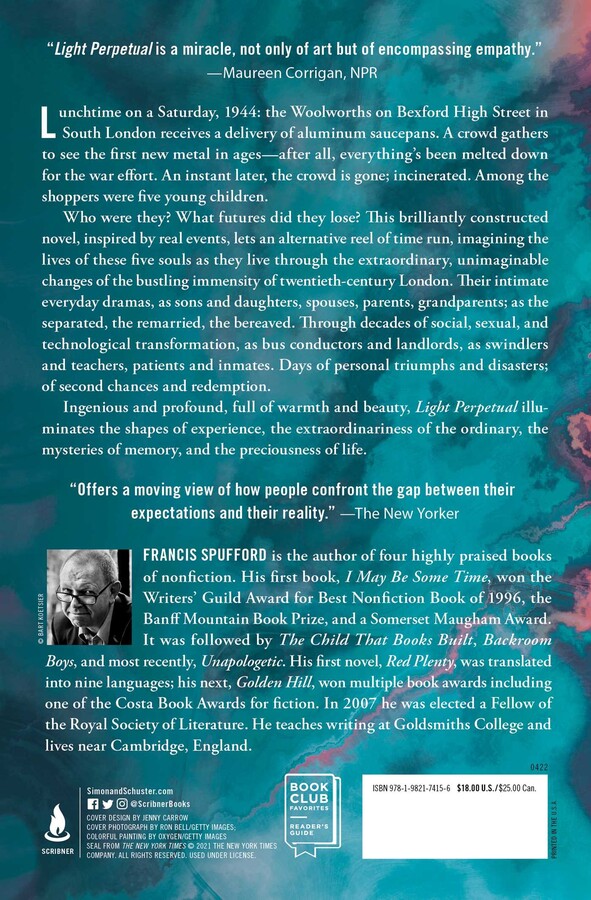

From the critically acclaimed and award‑winning author of Golden Hill, an “extraordinary…symphonic…casually stunning” (The Wall Street Journal) novel tracing the infinite possibilities of five lives in the bustling neighborhoods of 20th-century London.

Lunchtime on a Saturday, 1944: the Woolworths on Bexford High Street in South London receives a delivery of aluminum saucepans. A crowd gathers to see the first new metal in ages—after all, everything’s been melted down for the war effort. An instant later, the crowd is gone; incinerated. Among the shoppers were five young children.

Who were they? What futures did they lose? This brilliantly constructed novel, inspired by real events, lets an alternative reel of time run, imagining the lives of these five souls as they live through the extraordinary, unimaginable changes of the bustling immensity of twentieth-century London. Their intimate everyday dramas, as sons and daughters, spouses, parents, grandparents; as the separated, the remarried, the bereaved. Through decades of social, sexual, and technological transformation, as bus conductors and landlords, as swindlers and teachers, patients and inmates. Days of personal triumphs and disasters; of second chances and redemption.

Ingenious and profound, full of warmth and beauty, Light Perpetual “offers a moving view of how people confront the gap between their expectations and their reality” (The New Yorker) and illuminates the shapes of experience, the extraordinariness of the ordinary, the mysteries of memory, and the preciousness of life.

Excerpt

The light is grey and sullen; a smoulder, a flare choking on the soot of its own burning, and leaking only a little of its power into the visible spectrum. The rest is heat and motion. But for now the burn-line still creeps inside the warhead’s casing. It is a thread-wide front of change propagating outward from the electric detonator, through the heavy mass of amatol. In front a yellow-brown solid, slick and brittle as toffee: behind, a seething boil of separate atoms, violently relieved of all the bonds between that made them trinitrotoluene and ammonium nitrate, and just about to settle back into the simplest of molecular partnerships. Soon they will be gases. Hot gases, hotter than molten metal, far hotter; and suddenly, churningly abundant; and so furiously compacted now into a space too small for them that they would burst the casing imminently on their own. If the casing were still going to be there. If it were not itself going to disappear into a steel mist the instant the burn-line reaches it.

Instants. This instant, before the steel case vanishes, is one ten-thousandth of a second long. A hairline crack in a Saturday lunchtime in November 1944. But look closer. The crack has width. It has duration. Can it not, itself, be split in two? And split again, and again, and again, divided and subdivided ad infinitum, with no stopping point? Does it not, itself, contain an abyss? The fabric of ordinary time is all hollow beneath, opening into void below void, gulf behind gulf. Every moment you care to define proving on examination to be a close-packed sheaf of finer, and yet finer ones without end; finer, in fact, always and forever, than whatever your last guess was. Matter has its smallest, finite subdivisions. Time does not. One ten-thousandth of a second is a fat volume of time, with onion-skin pages uncountable. As uncountable, no more or less, than all the pages would be in all the books making up all the elapsed time in the universe. This book of time has no fewer pages than all the books put together. Each of the parts is as limitless as the whole, because infinities don’t come in larger and smaller sizes. They are all infinite alike. And yet somehow from this lack of limit arises all our ordinary finitude, our beginnings and ends. As if a pontoon had been laid across the abyss, and we walk it without noticing; as if the experience of this second, then this one, this minute then this one, here, now, succeeding each other without stopping, without appeal, and never quite enough of them, until there are no more of them at all—arose, somehow, as a kind of coagulation (a temporary one) of the nothing, or the everything, that yawns unregarded under all years, all Novembers, all lunchtimes. Do we walk, though? Do we move in time, or does it move us? This is no time for speculation. There’s a bomb going off.

This particular Saturday lunchtime, Woolworths on Lambert Street in the Borough of Bexford has a delivery of saucepans, and they are stacked on a table upstairs, gleaming cleanly. No one has seen a new pan for years, and there’s an eager crowd of women round the table, purses ready, kids too small to leave at home brought along to the shop. There’s Jo and Valerie with their mum, wearing tam-o’-shanters knitted from wool scraps; Alec with his, spindly knees showing beneath his shorts; Ben gripped firmly by his, and looking slightly mazed, as usual; chunky Vernon with his grandma, product of a household where they never seem to run quite as short of the basics as other people do. The women’s hands reach out towards the beautiful aluminium, but a human arm cannot travel far in a ten-thousandth of a second, and they seem motionless. The children stand like statues executed in flesh. Vern’s finger is up his nose. Something is moving visibly, though, even with time at this magnification. Over beyond the table, by the rack of yellowed knitting patterns, something long and sleek and sharp is coming through the ceiling, preceded by a slow-tumbling cloud of plaster and bricks and fragmented roof tiles. Amid the twinkling debris the tapering cone of the warhead has a geometric dignity as it slides floorward, the dull green bulk of the rocket pushing into sight behind, inch by inch. Inside the cone the amatol is already burning. Shoppers, saucepans, ballistic missile: what’s wrong with this picture? No one is going to tell us. Jo and Alec, as it happens, are looking in the right direction. Their gaze is fixed on the gap between the shoulders of Mrs. Jones and Mrs. Canaghan where the rocket is gliding into view. But they can’t see it. Nobody can. The image of the V-2 is on their retinas, but it takes far longer than a ten-thousandth of a second for a human eye to process an image and send it to a brain. Much sooner than that, the children won’t have eyes any more. Or brains. This instant—this interval of time, measurably tiny, immeasurably vast—arrives unwitnessed, passes unwitnessed, ends unwitnessed. And yet it is a real moment. It really happens. It really takes its necessary place in the sequence of moments by which 910 kilos of amatol are delivered among the saucepans.

Then the burn-line touches the metal. The name for what happens next is brisance. The moving thread of combustion, all combustion done, becomes a blast wave pushing on and out in the same directions, driven by the pressure of the livid gas behind. And what it touches, it breaks. A spasm of deformation, of dislocation, passes through every solid thing, shattering it to fragments that then accelerate outward themselves at the forefront of the wave. Knitting patterns. Rack. Glass sign hanging from chains, reading HABERDASHERY. Wooden table. Pans. Much-darned brown worsted hand-me-down served-three-siblings horn-buttoned winter coat. Skin. Bone. The size of the fragments is determined by the distance from the centre of the blast. Closest in, just particles: then flecks, shreds, morsels, lumps, pieces, and furthest out, where the energy of the wave is widest spread, whole mangled yard-wide fractions of wall or door or flagstone or tram-stop sign, torn loose and sent spinning across the street. The blast goes mainly down at first, because of the shape of the warhead, through the first floor and the ground floor and the cellar of Woolworths and into the London clay, where it scoops a roughly hemispheric crater before rebounding up and out with a pulse that carries most of the shattered fabric of the building with it. A dome of debris expands. The shops to left and right of Woolworths are ripped open to the air along the slanting upward lines of the dome’s edge. A blizzard of metal jags and brick flakes scours Lambert Street, both ways. The buildings opposite heave and sag; all their windowpanes blow inward and stick in the walls behind in glittering spears and splinters. In the ground, a tremor pops gas mains and grinds the sections of water pipes apart. In the air, even where there is no abrading grit, no flying rain of bricks, a sudden invisible jolt of intense pressure travels outward in a ring. A tram just coming round the far bend from Lewisham rocks on its rails and halts, still upright; but through it from end to end passes the ripple that turns the clear air momentarily as hard as glass. At the very limits of the blast, small strange alterations take place, almost whimsical. Kitchen chairs shake their way a foot across the floor. A cupboard door falls open, and hoarded pre-war confetti trickles out. A one-ounce weight from the butcher’s right next door to Woolworths somehow flies right over Lambert Street, and the street beyond, to fall neatly through the open back upstairs window of a house in the next street beyond that, and lodge among the undamaged keys of an Underwood typewriter.

No need to slow time, now. There’s nothing to see which can’t be seen at the usual speed humans perceive at. Let it run, one second per second. The rubble of Lambert Street bounces and lies still. The hollow howl of the rocket’s descent is heard at last, outdistanced by the explosion. Then a ringing stillness. No one is alive in Woolworths to break it. All of the shoppers and the counter girls are dead, on all three floors; and everyone in the butcher’s on the left, and the post office on the right, except for one clerk with both legs broken, who happened to be leaning forward into the safe; and everyone in the tram queue on the pavement outside; and all the passers-by; and anyone standing by the window in the houses opposite; and all the travellers on the Lewisham tram, still upright in their seats in their hats and coats, but asphyxiated by the air-shock. Then, only then, from those furthest out in the circle of ruination, the first screams. And the sirens. And the fire brigade coming; and the middle-aged men and women of the ARP stumbling through the masonry with their spades; and the teenage boys and old men of the Light Rescue Service arriving, with their stretchers which they scarcely use, and their sacks which they do. And the attempt to separate out from the rest of broken Woolworths those particles, flecks, shreds, lumps and pieces that, previously, were parts of people; people being missed, waited for, despaired of, by the crowd gathering white-faced behind the tape at the end of the street.

Jo and Valerie and Alec and Ben and Vernon are gone. Gone so fast they cannot possibly have known what was happening, which some of those who mourn them will take for a comfort, and some won’t. Gone between one ten-thousandth of a second and the next, gone so entirely that it’s as if they’ve vanished into all that copious, immeasurable nothing just beneath the rickety scaffolding of hours and minutes. Their part in time is done. They have no share, any more, in what swells and breathes and tightens and turns and withers and brightens and darkens; in any of the changes of things. Nothing is possible for them that requires being to stretch from one instant to another over the gulfs of time. They cannot act, or be acted on. Cannot call, or be called. Do, or be done unto. There they aren’t. Meanwhile the matter that composed them is all still there in the crater, but it cannot ever, in any amount of time whatsoever, be reassembled. That’s time for you. It breaks things up. It scatters them. It cannot be run backwards, to summon the dust to rise, any more than you can stir milk back out of tea. Once sundered, forever sundered. Once scattered, forever scattered. It’s irreversible.

But what has gone is not just the children’s present existence—Vernon not trudging home to the house with the flitch of bacon hanging in the kitchen, Ben not on his dad’s shoulders crossing the park, astonished by the watery November clouds, Alec not getting his promised ride to Crystal Palace tomorrow, Jo and Valerie not making faces at each other over their dinner of cock-a-leekie soup. It’s all the futures they won’t get, too. All the would-be’s, might-be’s, could-be’s of the decades to come. How can that loss be measured, how can that loss be known, except by laying this absence, now and onwards, against some other version of the reel of time, where might-be and could-be and would-be still may be? Where, by some little alteration, some altered single second of arc, back in Holland where the rocket launched, it flew four hundred yards further into Bexford Park, and killed nothing but pigeons; or suffered a guidance failure, as such crude mechanisms do, and slipped unnoticed between the North Sea waves; or never launched at all, a hiccup in fuel deliveries meaning the soldiers of Batterie 485 spent all that day under the pine trees of Wassenaar waiting for the ethanol tanker, and smoking, and nervously watching the sky for RAF Mosquitoes?

Come, other future. Come, mercy not manifest in time; come knowledge not obtainable in time. Come, other chances. Come, unsounded deep. Come, undivided light.

Come dust.

Reading Group Guide

Get a FREE ebook by joining our mailing list today! Plus, receive recommendations for your next Book Club read.

Introduction

Journey through the changing of a big city through 1944 to 2009 from the viewpoints of five young people: Jo, Val, Vern, Alec, and Ben as they live through the extraordinary, unimaginable changes of the bustling immensity of twentieth-century London. Their intimate everyday dramas, as sons and daughters, spouses, parents, grandparents; as the separated, the remarried, the bereaved. Through decades of social, sexual, and technological transformation, as bus conductors and landlords, as swindlers and teachers, patients and inmates. Days of personal triumphs, disasters; of second chances and redemption. Light Perpetual is a stunning novel about what makes people who they are, from the author of Golden Hill.

Topics & Questions for Discussion

1. The opening chapter sets a sort of anti-scene for the rest of the book. Why do you think Spufford chose to begin the book the way he did?

2. There are many words specific to England (and even more specifically, twentieth-century London) in Light Perpetual (“dollybirds,” “skinheads,” “blancmange,” Nancy-boys,” money in “half-crowns and ten-bob notes”). As a group, keep track of these words as you come across them, and keep a running list of terms and definitions.

3. On page 37, when Alec is interviewing for a job (one he’s dreamed of getting), Hobson tries to talk him out of getting a union gig: “you’ve got a future ahead of you in the print, and that’s grand. That will see you and Sandra right. And I done my best to help. But you’re a bright boy. And I just wanted to say, so I had at least come out and said it, at least once—is this what you really want?” Compare Alec in pages 29–40 with Alec in pages 275–95. How has the way he thinks about work and family changed, or has it stayed the same?

4. Jo is one of the stronger female characters in Light Perpetual. In the first standalone chapter about her, she’s observing young men around her discuss their tastes in music. She muses, “In her experience nothing good at all comes from making the faintest criticism of men’s expertise in what men think of as men’s stuff” (page 77). What does that tell you about her understanding of the gender roles she’s been born into?

5. Starting on page 129, we rejoin Jo, who is now working in LA. How does her relationship with Ricky call back to her interaction with the boys on page 77, and what do you think she’s learned since then?

6. In Light Perpetual, there is a lot of subtle commentary on the roles that were assigned to men and women in twentieth-century London. The stories of Val and Jo speak to this especially. When we first meet Val (page 40), she’s on a date with Alan, and then meets Mike. What does her first interaction with Mike tell you about what their relationship might become?

7. Mike is part of the skinhead youth culture of white working-class London in the 1970s, a violent and racist reaction against the changing ethnic makeup of the city. In fact, he has gone all the way into neo-Nazism. Val never directly challenges Mike’s harmful views, but she does ponder that “He is the only beautiful thing in her life, as well as being the cause of all the ugly ones” (page 163). After finishing Val’s story, what do you think of this statement about Mike? What does their marriage become for her?

8. When we meet Ben early in his life, he’s on Largactil (an antipsychotic) and in an old-fashioned insane asylum. Later, he works for the city bus system and has an addiction to marijuana. The author does not detail the name of his mental state, but what do you suppose he is dealing with, and how do you see him growing in self-sufficiency?

9. Later on, Ben has met Marsha and appears to be in a very happy marriage with a woman who has a different cultural and religious background than him. What do you make of his conversion experience to her lifestyle and religion?

10. Val and Jo are the main women in Light Perpetual, and their lives couldn’t have ended up differently. What are the differences in their motivations in life, and how did those drive them in such different directions?

11. On pages 242–57, we get a glimpse of what Alec’s later years have become—a stay-at-home grandad who considers himself “domesticated” while his wife Sandra goes out and works. What is Alec’s perception of himself? What makes him happy about where he is, and what is pulling him away?

12. Once you’ve finished the book, compare and contrast the lives and careers of Vern and Alec. How are their motivations different? Where has that landed each of them?

13. The book ends with Ben. What do you make of the almost hymn-like last passage, as Ben slowly dies? Why do you think Spufford chose to finish the novel with Ben’s story?

Enhance Your Book Club

1. There are five different protagonists in Light Perpetual: Jo, Val, Vern, Alec, and Ben. As you read the book and are introduced to each character, write a brief character sketch about each of them (any defining physical features, clues about their livelihoods, and implications of their romantic relationships).

2. On page 262, when Vern is listening to Dame Kiri Te Kanawa in the car with his daughter Becky, he observes that the singer is “a woman with some heft on her, too, a woman with an actual figure.” As a group, look up photos of women and men in London from the early 1940s to 2009. How do beauty and body standards change over time?

3. Once you’ve finished Light Perpetual, watch the film Billy Elliot. The plot involves a young boy coming of age in England and watching his family’s involvement in the 1984–85 miners’ strike. Discuss how the working class pictured in Billy Elliot is similar to and different from the working class in Light Perpetual (particularly the story of Alec and his son Gary).

4. Throughout the book, the music the characters make and listen to provides a soundtrack. You can find most of the songs on YouTube or search on Spotify for the Light Perpetual playlist. Listen to these songs and discuss what the music tells you about how London has altered since 1944.

Product Details

- Publisher: Scribner (April 5, 2022)

- Length: 336 pages

- ISBN13: 9781982174156

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

*A New York Times Notable Book of 2021*

"A God’s-eye meditation on mutability and loss. . . . an extraordinary novel in terms of its variety of character, symphonic language and spiritual reach. . . . [Spufford is] such a beautiful writer, casually stunning in his language and perceptions. . . . Light Perpetual is a miracle, not only of art but of encompassing empathy.” —Maureen Corrigan, The Wall Street Journal

"Offers a moving view of how people confront the gap between their expectations and their reality." —The New Yorker

"Vividly imagined. . . . Spufford is a fluent writer, bringing a deft touch to the emotional force fields of parents and their children. . . . richly drawn.” —Christopher Benfy, The New York Times Book Review

"Heady, vivid, ecstatically precise. . . . uncannily good. . . . Light Perpetual is the sort of novel that’s carried by its descriptions, passages that transform the ordinary into the transcendent and leave us marveling.” —Laura Miller, Slate

“Just finished Light Perpetual by Francis Spufford. My God he can write. And one of the best opening chapters and closing chapters you'll ever read.”—Richard Osman, author of The Thursday Murder Club and The Man Who Died Twice

"Spufford’s storytelling is beautiful, paced, and engaging. . . . [He] makes the case that all lives are inherently interesting if we look at them closely enough." —Lit Hub, "Our Favorite Books of 2021"

“Magical . . . stunning. . . . Thanks to Spufford’s narrative wizardry, all five protagonists come to vivid life in this spectacularly moving story.” —Publishers Weekly, STARRED review

“[A] richly imagined mosaic. . . . [T]he characters are complex, engaging, memorable. Spufford does indeed bring them to life. He also brings depth and detail to every vignette, from a boy’s view of soccer to hot-lead typesetting, a neo-Nazi concert, or a trip on a double-decker bus. . . . Entertaining and unconventional.” —Kirkus Reviews, STARRED review

“Graceful. . . . Light Perpetual derives considerable power from dramatizing the experiences its characters missed: the chance to build and lose a fortune, to see one’s dreams realized or else rerouted toward more modest achievements, or just to hold a loved one’s hand." —BookPage, STARRED review

"Five children die in 1944, but imagined glimpses of their unlived lives generate powerful moments of reflection and redemption... Spufford’s second novel swells with the same lively, intimate prose as his celebrated debut, The Golden Hill (2017). But its unconventional framing and larger, more contemporary themes makes it an even stronger book." —Booklist, STARRED review

"Spufford has the compassion, wit, and moral sense of a C.S. Lewis, and the literary dazzle and inventiveness of a David Mitchell. Is this the book of the year? I thought so.” —Joe Hill

“I was reminded of the death-defying bent of two other recent novels—Kate Atkinson’s Life After Life and Paul Auster’s 4 3 2 1 — both of which share with Light Perpetual a kind of radiant goodness, a sense that the world is a better place for having such books within them…. Light Perpetual’s brilliance lies in the emotion and drama it wrings from the ordinary—but profoundly meaningful—experiences of its protagonists.” —Financial Times

“With bold metaphysical engineering, the Golden Hill author conjures miraculous everyday existence…Light Perpetual is something new and brave. With exceptional care, with a loving shrewdness that’s a little Hogarthian, Spufford catches the voices and hopes of five not-dead working-class south Londoners, and the people who change and shape them.” —The Guardian

“Radiant with hope and grace and courage . . . I loved it.” —Sarah Perry, author of The Essex Serpent

“Dazzling ... [Spufford is] one of the finest prose stylists of his generation. If his stories grip, his sentences practically glow.” —The Times (UK)

“A brilliant, attention-grabbing, capacious experiment with fiction.” —Observer (UK)

“Boundlessly rich.” —The Telegraph (UK)

“Gleams with literary finesse. Keen perception and exact verbal flair...abound...The novel’s overarching feat is to resurrect with marvellous vitality not just its central five figures, but six transformative decades of London life.” —Sunday Times (UK)

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Light Perpetual Trade Paperback 9781982174156

- Author Photo (jpg): Francis Spufford © Antonio Olmos(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit