Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

Table of Contents

About The Book

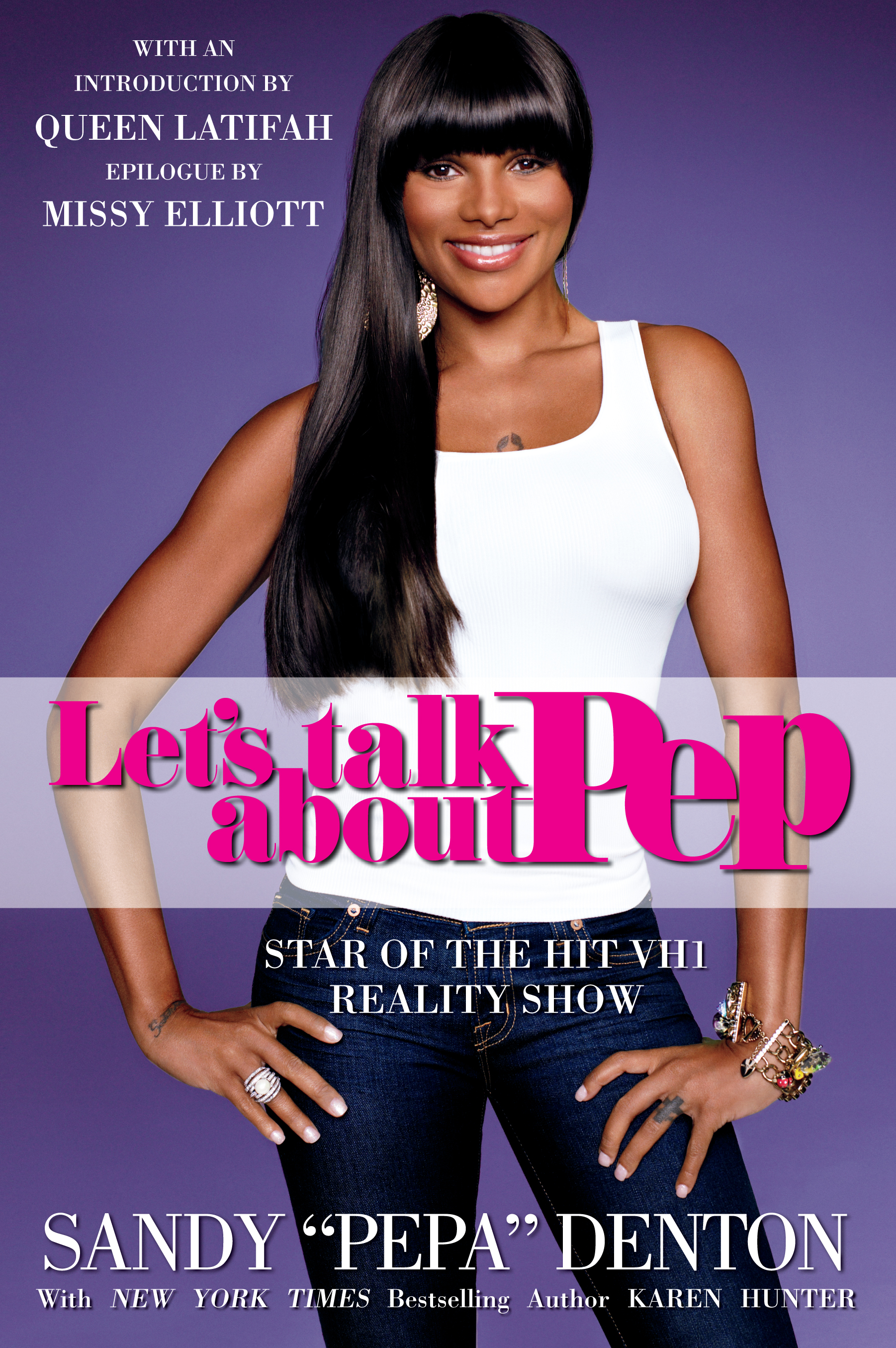

From Sandy “Pepa” Denton—rap legend and outspoken reality TV star—comes the juicy tell-all in which she talks about sex, music, life, love, fame, and so much more.

The spiciest ingredient in the legendary rap group Salt-N-Pepa, fans know Sandy Denton as Pep, or Pepa, the fun-loving half of Salt-N-Pepa. But behind the laughs and the smiles is a whole lot of pain, and for the first time in Let’s talk About Pep, she candidly talks about her troubled childhood, surviving abuse, her first encounters with Cheryl “Salt” James, instant success, her failed marriages and escape from domestic abuse, and her triumphant comeback on reality shows like The Surreal Life and The Salt-N-Pepa Show.

Filled with surprising insights, outrageous anecdotes, and celebrity cameos—including Queen Latifah, Martin Lawrence, Janice Dickinson, Missy Elliott, L.L. Cool J, Ron Jeremy, Lisa “Left Eye” Lopez, and many others—Let’s Talk About Pep offers a fascinating glimpse behind the fame, family, failures, and success...and into the faithful heart of a woman who will always treasure the good friends she found along the way.

Every bit as captivating and provocative as her Grammy Award-winning music, this story reveals the real Pepa—upfront, uncensored, unstoppable—a true pioneer, survivor, and inspiration to women everywhere.

The spiciest ingredient in the legendary rap group Salt-N-Pepa, fans know Sandy Denton as Pep, or Pepa, the fun-loving half of Salt-N-Pepa. But behind the laughs and the smiles is a whole lot of pain, and for the first time in Let’s talk About Pep, she candidly talks about her troubled childhood, surviving abuse, her first encounters with Cheryl “Salt” James, instant success, her failed marriages and escape from domestic abuse, and her triumphant comeback on reality shows like The Surreal Life and The Salt-N-Pepa Show.

Filled with surprising insights, outrageous anecdotes, and celebrity cameos—including Queen Latifah, Martin Lawrence, Janice Dickinson, Missy Elliott, L.L. Cool J, Ron Jeremy, Lisa “Left Eye” Lopez, and many others—Let’s Talk About Pep offers a fascinating glimpse behind the fame, family, failures, and success...and into the faithful heart of a woman who will always treasure the good friends she found along the way.

Every bit as captivating and provocative as her Grammy Award-winning music, this story reveals the real Pepa—upfront, uncensored, unstoppable—a true pioneer, survivor, and inspiration to women everywhere.

Excerpt

Let's Talk About Pep

CHAPTER ONE The Chameleon’s Curse

I WAS BORN IN JAMAICA. My earliest memories are of being on my grandmother’s farm in St. Elizabeth’s, which was considered the cush-cush or upper-class section of Jamaica, between Negril and Kingston. We lived in what they called the country, and I just remember running free and not having a care in the world. I didn’t come to the States until I was about six. That’s when life became complicated.

I was the youngest of eight. The baby. My mother said I was the cutest baby she had ever seen. When I six months old, she entered me in this contest to be the face of O-Lac’s, which was Jamaica’s version of Gerber baby food. They were looking for a fat, healthy baby, and I won the contest. I was the face—this smiling, fat, toothless baby—on O-Lac’s for years. I guess I was destined for stardom.

My parents moved to the United States when I was three. One by one, each of my sisters left, too. I know that my father had a government job in Jamaica. I don’t know what happened with it. I just remember talk of “opportunity” and “education” in America.

In Jamaica, you had to pay for education after primary school. And getting an education was big in my family. So maybe that’s why they left. I never asked. You didn’t ask questions when I was growing up. My family was traditional, and kids didn’t ask adults questions, you just accepted things—whatever those things were.

I ended up being in Jamaica with my grandmother and one of my older sisters. My parents would come back from time to time, but I was there for a couple of years before they finally moved me to the States, too.

I loved my family, but I never quite fit in with them. I was always a little bit different. My sister Dawn was the rebel, the black sheep. I watched how she used to get beatings—I mean real beatings, not some little old spankings—and I didn’t want any of that. My parents, mostly my father, tried to beat the rebellion out of Dawn. It didn’t work, though. It might have made her more rebellious.

By the time I got to the States, she was hanging out with the wrong crowds, staying out way beyond the curfew and trying to sneak in the house and getting caught. She used to steal my father’s gun. She would fight. And eventually she turned to drugs. But that was my girl! I looked up to Dawn. I just didn’t want to suffer any of those beatings, so I was a “good girl.” I did what I was told—as far as they knew—and I stayed out of trouble. But I was always a little different.

When I was on that farm in Jamaica, I would get into all kinds of trouble. One day I remember I got ahold of a machete. I was only like five years old. Don’t ask me how I got it or where I got it from, but I had this machete and a bucket. I went around the farm looking for lizards or chameleons. They had all kinds of creatures on this farm, but there were a lot of chameleons. I was fascinated by them, watching them go to a green plant and turn green, then to the ground and turn brown. I walked around looking for them, and I would chop them in half and throw them into my bucket.

By the end of the day, I had a bucket full of chopped-up lizards. My sister came out and saw what I was doing and she scared the hell out of me.

“What is that you’re doing?!” she screamed. “Dem lizards gwon ride ya.”

She was telling me that the lizards were going to haunt me. That my doing that had unleashed some kind of curse.

“Dem gwon ride ya!” my sister kept saying in her Jamaican patois.

Well, they did ride me. As I got older, a lot of my friends would tell me, “You’re such a chameleon.”

It was true. I was real good at blending in. I was good at taking on whatever was around me. If I hung out with thugs, I would be a thug. If I hung out with a prince, it was nothing for me to become royalty. My ability to fit in has been a blessing, but also a curse.

The very thing that got me into Salt-N-Pepa—going with the flow and doing what I was told—was the same thing that got me in a lot of bad situations. Being a chameleon or just going with whatever wasn’t good for me. It allowed me to put up with things I shouldn’t have put up with. It allowed me to be with people I should not have been with because I wasn’t able to just be myself and say no or walk away. It never let me ask, “What do I want out of life?” It never allowed me to really think about me and my needs first.

I wanted to fit in. I wanted to be accepted. I wanted people to like me.

CHAPTER ONE The Chameleon’s Curse

I WAS BORN IN JAMAICA. My earliest memories are of being on my grandmother’s farm in St. Elizabeth’s, which was considered the cush-cush or upper-class section of Jamaica, between Negril and Kingston. We lived in what they called the country, and I just remember running free and not having a care in the world. I didn’t come to the States until I was about six. That’s when life became complicated.

I was the youngest of eight. The baby. My mother said I was the cutest baby she had ever seen. When I six months old, she entered me in this contest to be the face of O-Lac’s, which was Jamaica’s version of Gerber baby food. They were looking for a fat, healthy baby, and I won the contest. I was the face—this smiling, fat, toothless baby—on O-Lac’s for years. I guess I was destined for stardom.

My parents moved to the United States when I was three. One by one, each of my sisters left, too. I know that my father had a government job in Jamaica. I don’t know what happened with it. I just remember talk of “opportunity” and “education” in America.

In Jamaica, you had to pay for education after primary school. And getting an education was big in my family. So maybe that’s why they left. I never asked. You didn’t ask questions when I was growing up. My family was traditional, and kids didn’t ask adults questions, you just accepted things—whatever those things were.

I ended up being in Jamaica with my grandmother and one of my older sisters. My parents would come back from time to time, but I was there for a couple of years before they finally moved me to the States, too.

I loved my family, but I never quite fit in with them. I was always a little bit different. My sister Dawn was the rebel, the black sheep. I watched how she used to get beatings—I mean real beatings, not some little old spankings—and I didn’t want any of that. My parents, mostly my father, tried to beat the rebellion out of Dawn. It didn’t work, though. It might have made her more rebellious.

By the time I got to the States, she was hanging out with the wrong crowds, staying out way beyond the curfew and trying to sneak in the house and getting caught. She used to steal my father’s gun. She would fight. And eventually she turned to drugs. But that was my girl! I looked up to Dawn. I just didn’t want to suffer any of those beatings, so I was a “good girl.” I did what I was told—as far as they knew—and I stayed out of trouble. But I was always a little different.

When I was on that farm in Jamaica, I would get into all kinds of trouble. One day I remember I got ahold of a machete. I was only like five years old. Don’t ask me how I got it or where I got it from, but I had this machete and a bucket. I went around the farm looking for lizards or chameleons. They had all kinds of creatures on this farm, but there were a lot of chameleons. I was fascinated by them, watching them go to a green plant and turn green, then to the ground and turn brown. I walked around looking for them, and I would chop them in half and throw them into my bucket.

By the end of the day, I had a bucket full of chopped-up lizards. My sister came out and saw what I was doing and she scared the hell out of me.

“What is that you’re doing?!” she screamed. “Dem lizards gwon ride ya.”

She was telling me that the lizards were going to haunt me. That my doing that had unleashed some kind of curse.

“Dem gwon ride ya!” my sister kept saying in her Jamaican patois.

Well, they did ride me. As I got older, a lot of my friends would tell me, “You’re such a chameleon.”

It was true. I was real good at blending in. I was good at taking on whatever was around me. If I hung out with thugs, I would be a thug. If I hung out with a prince, it was nothing for me to become royalty. My ability to fit in has been a blessing, but also a curse.

The very thing that got me into Salt-N-Pepa—going with the flow and doing what I was told—was the same thing that got me in a lot of bad situations. Being a chameleon or just going with whatever wasn’t good for me. It allowed me to put up with things I shouldn’t have put up with. It allowed me to be with people I should not have been with because I wasn’t able to just be myself and say no or walk away. It never let me ask, “What do I want out of life?” It never allowed me to really think about me and my needs first.

I wanted to fit in. I wanted to be accepted. I wanted people to like me.

Product Details

- Publisher: MTV Books (February 16, 2010)

- Length: 224 pages

- ISBN13: 9781416551423

Browse Related Books

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Let's Talk About Pep Trade Paperback 9781416551423(3.4 MB)