Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

LIST PRICE $10.99

PRICE MAY VARY BY RETAILER

Get 30% off hardcovers with code MOM30, plus free shipping on orders of $40 or more. Terms apply.

Buy from Other Retailers

Table of Contents

About The Book

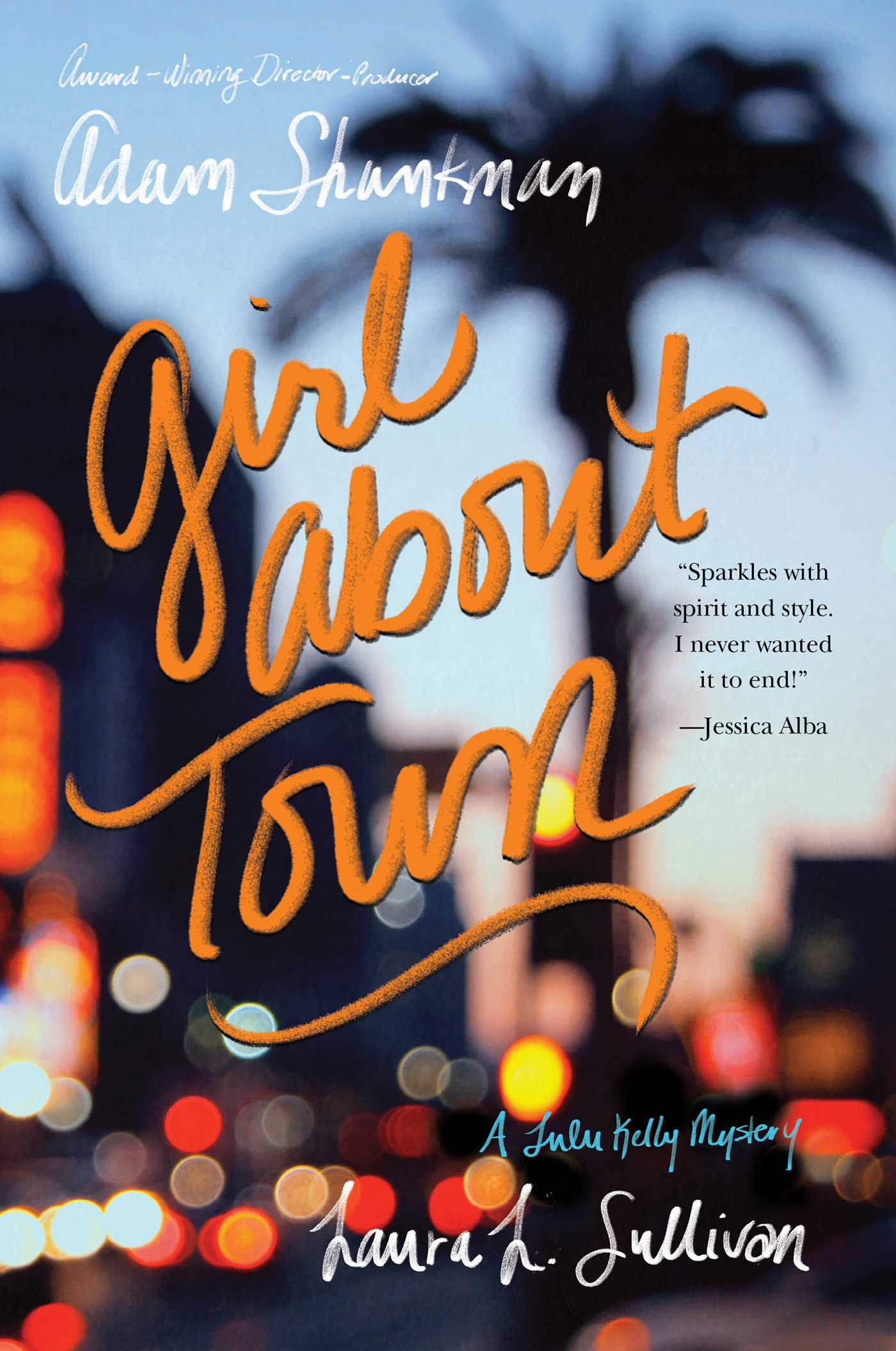

“Cinematic pacing, a compelling whodunit, and the glitzy aura of golden age Hollywood combine in this star-studded novel” (Booklist) from acclaimed film producer/director Adam Shankman and coauthor Laura Sullivan.

Not too long ago, Lucille O’Malley was living in a tenement in New York. Now she’s Lulu Kelly, Hollywood’s newest It Girl. She may be a star, but she worries that her past will catch up with her. Back in New York she witnessed a Mafia murder, and this glamorous new life in Tinseltown is payment for her silence.

Dashing Freddie van der Waals, the only son of a New York tycoon, was a playboy with the world at his feet. But when he discovered how his corrupt father really made the family fortune, Freddie abandoned his billions and became a vagabond. He travels the country in search of redemption and a new identity, but his father will stop at nothing to bring him home.

When fate brings Lulu and Freddie together, sparks fly—and gunshots follow. Suddenly Lulu finds herself framed for attempted murder. Together, she and Freddie set out to clear her name. But can they escape their pasts and finally find the Hollywood ending they long for?

Not too long ago, Lucille O’Malley was living in a tenement in New York. Now she’s Lulu Kelly, Hollywood’s newest It Girl. She may be a star, but she worries that her past will catch up with her. Back in New York she witnessed a Mafia murder, and this glamorous new life in Tinseltown is payment for her silence.

Dashing Freddie van der Waals, the only son of a New York tycoon, was a playboy with the world at his feet. But when he discovered how his corrupt father really made the family fortune, Freddie abandoned his billions and became a vagabond. He travels the country in search of redemption and a new identity, but his father will stop at nothing to bring him home.

When fate brings Lulu and Freddie together, sparks fly—and gunshots follow. Suddenly Lulu finds herself framed for attempted murder. Together, she and Freddie set out to clear her name. But can they escape their pasts and finally find the Hollywood ending they long for?

Excerpt

Girl About Town ONE

It was never quiet where Lucille lived. Sometimes, in rare free moments away from the monotony of a washerwoman’s steam and scalding water, her mother, Ida, would lovingly read aloud from one of the few precious books that hadn’t been pawned. Shakespeare’s arcadian visions or poems about sylvan greenery, where thoughts were never interrupted by anything more jarring than birdsong and the baaing of sheep . . . Lucille would close her eyes, listening to her mother’s gentle schoolteacher voice, and dream about a place like that. Though maybe without the sheep. She’d seen raw wool loaded into the textile factory, and from what she witnessed, sheep must be as filth-crusted and degenerate as any Lower East Side bum. How clean things are in poetry, how dirty in real life.

In their tiny tenement, eight people lived in two small rooms. Her father, in a steady decline since an injury in the Great War, was now practically bedridden, unable to work, or do much more than sleep or beg for the morphine that helped that sleep come when they could afford it. They could rarely afford anything beyond bare sustenance, but sometimes even that was denied to give her father the gift of dreamless slumber. Cabbage or peace, it came to. A holiday was cabbage and peace.

Her two older brothers jauntily ran the streets most of the day and half the night, coming home drunk, grunting, and penniless—but they’d had money at some point every day, to get the liquor, so why didn’t they ever bring any of it home? The three youngest, two girls and a boy, were in school for part of the day. But even when the tiny apartment was half empty, it was still tumultuous. People were on every side of them, roaring through the cardboard-thin walls, stomping on the ceiling, brawling below their feet, bickering at their doorstep. Life in a Lower East Side tenement was a constant cacophony of the worst sounds mankind could make.

Lucille should have been in school, but she’d dropped out a few months ago to help her mother in their small, struggling laundry business. Truant officers didn’t seem to care whether a poor girl in the slums got a proper education. Now Lucille spent her days dashing through the city, picking up dirty clothes and delivering them again the next day, pristine.

Her mother specialized in dainty items—the lace shawls of proud old women, the undergarments of flighty young women—and had amassed a small but devoted clientele. The tubs of boiling water and lye took up half of their living space, but she washed only small precious things and could charge more, since the delicate furbelows required special care. Sometimes she spent an hour coaxing the frills on a fine set of knickers into place. A young woman rich enough to wear such undergarments could easily find someone to pay for their expert cleaning.

But as the Depression deepened, her clientele was dwindling. People’s investments weren’t so secure anymore, and in times of financial crisis, married men leave their mistresses for their wives.

“Mother,” Lucille said that evening, as she’d said many evenings before, “you could try again, couldn’t you? Just try? Maybe someone needs a teacher now.”

But her mother only shook her head and rubbed tallow into her red, cracked hands. “It’s too late for me,” she said, her voice weary. “This is my life, and I accept it. Yes, it’s difficult, and perhaps not very . . . well . . . pretty. But I have you and your brothers and sisters, and you all bring more beauty into my life than I could have ever hoped for.” Then, seeing her daughter’s creased brow, she caught her in her arms. “It’s not all bad, is it?” she asked Lucille. “We’ve got each other.” She took her daughter’s smooth hands in her work-roughened ones and pulled her into a swaying motion. “And remember, you don’t need money to dance.”

Suddenly, miraculously, her despondency was gone. She sang a Gershwin tune and spun her daughter. Both of them were giggling as they tried the modern steps. But her mother had grown up with ragtime, and a moment later she abandoned the jazz hit for the music of her own teen years, humming and tapping out the syncopated rhythms of Scott Joplin.

They didn’t happen often, these moments of abandon and sheer fun. When they did, they were a tonic for all that was wrong with their lives. Her mother’s sweet lilting voice, the energy of their dancing, seemed to drive away every worry. Lucille and her mother had been dancing together almost since she could walk, perfecting their little routines of everything from waltzes and tangos to their take on modern fox-trots and swing.

But they never had more than a few moments of joy. Loutish reality, like a drunken boor, inevitably tapped on her shoulder and cut into their dance. Now their gaiety was interrupted by a low groan from Lucille’s father. They stopped abruptly, looking guiltily toward the sound. Lucille pressed her lips together, waiting to see if he might go back to sleep.

His fit came on him strongly. It started with moans that rose and rose until they crescendoed in agonized cries. Lucille never knew if it was the pain that drove him mad at times or the memories of trench warfare. He never meant to be violent, she was sure, but every one of them had been bruised when they’d tried to hold him down during his fits.

Their reprieve was over. “I’ll stay and help you,” Lucille told her mother.

“No, Lucille, you go, or Mrs. Fahntille and Mr. Rosen will be cross.” She handed over a small packet of knickers and slips wrapped in white paper and gave her a kiss on the cheek. Lucille watched her mother’s careworn eyes turn to the lumpy bed in the corner of the room.

Lucille bit her lip. She pitied her father, of course, but she wondered if he would be in the same state whether he was rich or poor. Would the nightmares chase him on the softest feather bed, the old pains bite him through the finest patent coil-spring mattress? In his throes, would he strike out at the nation’s finest physicians as indiscriminately as he unconsciously struck his own wife when she lay a cooling compress on his fevered brow?

No, the one she really felt sorry for was her mother. At times—frequently when Lucille was a child, less often now—she could see in her mother the vital spark of youth. It came when she danced, when she read some favorite poem aloud. Within her still, though buried deep, were all the hopes of her girlhood, giddy and free, and also the more domestic hopes of her young womanhood as a new bride and mother. Now, Lucille could see, the weight of seven people pressed heavily on her shoulders. Every morsel of food that passed their lips came from her labor. What if she should get sick? The loss of only a few days’ income would be enough to put them on the streets and cast them all, particularly the girls, into a degradation from which there would be no escape.

Every second of every day, this fear hid in her mother’s eyes. Yet there was still, Lucille could see, an almost childlike hope, little more than a wish made on a lucky clover, that things might change. What Lucille wouldn’t do to feed that tiny hopeful spark in her mother’s breast until it burst into a flame that would engulf all their wretchedness and poverty!

Lucille’s dreams were undoubtedly fresher than her mother’s, but to her they seemed no more possible. What could she, a sixteen-year-old girl with no skills and hardly any education, do to save her family?

“Skedaddle!” Her mother sighed again and gave her a pat on the rump, sending her out into the world.

And so, feeling guiltily relieved, Lucille left, stepping over a familiar drunk in the hallway, skirting half-naked children on the stoop, and ignoring the wolf whistle.

But I have to get ahead, somehow, she thought desperately. Ahead, and out, away from this filth.

On that evening Lucille would have done anything to escape her situation—if only she’d known how. . . .

Then she saw what she saw, that terrible thing—and did what she did, that terrible thing—and her entire life changed.

It was never quiet where Lucille lived. Sometimes, in rare free moments away from the monotony of a washerwoman’s steam and scalding water, her mother, Ida, would lovingly read aloud from one of the few precious books that hadn’t been pawned. Shakespeare’s arcadian visions or poems about sylvan greenery, where thoughts were never interrupted by anything more jarring than birdsong and the baaing of sheep . . . Lucille would close her eyes, listening to her mother’s gentle schoolteacher voice, and dream about a place like that. Though maybe without the sheep. She’d seen raw wool loaded into the textile factory, and from what she witnessed, sheep must be as filth-crusted and degenerate as any Lower East Side bum. How clean things are in poetry, how dirty in real life.

In their tiny tenement, eight people lived in two small rooms. Her father, in a steady decline since an injury in the Great War, was now practically bedridden, unable to work, or do much more than sleep or beg for the morphine that helped that sleep come when they could afford it. They could rarely afford anything beyond bare sustenance, but sometimes even that was denied to give her father the gift of dreamless slumber. Cabbage or peace, it came to. A holiday was cabbage and peace.

Her two older brothers jauntily ran the streets most of the day and half the night, coming home drunk, grunting, and penniless—but they’d had money at some point every day, to get the liquor, so why didn’t they ever bring any of it home? The three youngest, two girls and a boy, were in school for part of the day. But even when the tiny apartment was half empty, it was still tumultuous. People were on every side of them, roaring through the cardboard-thin walls, stomping on the ceiling, brawling below their feet, bickering at their doorstep. Life in a Lower East Side tenement was a constant cacophony of the worst sounds mankind could make.

Lucille should have been in school, but she’d dropped out a few months ago to help her mother in their small, struggling laundry business. Truant officers didn’t seem to care whether a poor girl in the slums got a proper education. Now Lucille spent her days dashing through the city, picking up dirty clothes and delivering them again the next day, pristine.

Her mother specialized in dainty items—the lace shawls of proud old women, the undergarments of flighty young women—and had amassed a small but devoted clientele. The tubs of boiling water and lye took up half of their living space, but she washed only small precious things and could charge more, since the delicate furbelows required special care. Sometimes she spent an hour coaxing the frills on a fine set of knickers into place. A young woman rich enough to wear such undergarments could easily find someone to pay for their expert cleaning.

But as the Depression deepened, her clientele was dwindling. People’s investments weren’t so secure anymore, and in times of financial crisis, married men leave their mistresses for their wives.

“Mother,” Lucille said that evening, as she’d said many evenings before, “you could try again, couldn’t you? Just try? Maybe someone needs a teacher now.”

But her mother only shook her head and rubbed tallow into her red, cracked hands. “It’s too late for me,” she said, her voice weary. “This is my life, and I accept it. Yes, it’s difficult, and perhaps not very . . . well . . . pretty. But I have you and your brothers and sisters, and you all bring more beauty into my life than I could have ever hoped for.” Then, seeing her daughter’s creased brow, she caught her in her arms. “It’s not all bad, is it?” she asked Lucille. “We’ve got each other.” She took her daughter’s smooth hands in her work-roughened ones and pulled her into a swaying motion. “And remember, you don’t need money to dance.”

Suddenly, miraculously, her despondency was gone. She sang a Gershwin tune and spun her daughter. Both of them were giggling as they tried the modern steps. But her mother had grown up with ragtime, and a moment later she abandoned the jazz hit for the music of her own teen years, humming and tapping out the syncopated rhythms of Scott Joplin.

They didn’t happen often, these moments of abandon and sheer fun. When they did, they were a tonic for all that was wrong with their lives. Her mother’s sweet lilting voice, the energy of their dancing, seemed to drive away every worry. Lucille and her mother had been dancing together almost since she could walk, perfecting their little routines of everything from waltzes and tangos to their take on modern fox-trots and swing.

But they never had more than a few moments of joy. Loutish reality, like a drunken boor, inevitably tapped on her shoulder and cut into their dance. Now their gaiety was interrupted by a low groan from Lucille’s father. They stopped abruptly, looking guiltily toward the sound. Lucille pressed her lips together, waiting to see if he might go back to sleep.

His fit came on him strongly. It started with moans that rose and rose until they crescendoed in agonized cries. Lucille never knew if it was the pain that drove him mad at times or the memories of trench warfare. He never meant to be violent, she was sure, but every one of them had been bruised when they’d tried to hold him down during his fits.

Their reprieve was over. “I’ll stay and help you,” Lucille told her mother.

“No, Lucille, you go, or Mrs. Fahntille and Mr. Rosen will be cross.” She handed over a small packet of knickers and slips wrapped in white paper and gave her a kiss on the cheek. Lucille watched her mother’s careworn eyes turn to the lumpy bed in the corner of the room.

Lucille bit her lip. She pitied her father, of course, but she wondered if he would be in the same state whether he was rich or poor. Would the nightmares chase him on the softest feather bed, the old pains bite him through the finest patent coil-spring mattress? In his throes, would he strike out at the nation’s finest physicians as indiscriminately as he unconsciously struck his own wife when she lay a cooling compress on his fevered brow?

No, the one she really felt sorry for was her mother. At times—frequently when Lucille was a child, less often now—she could see in her mother the vital spark of youth. It came when she danced, when she read some favorite poem aloud. Within her still, though buried deep, were all the hopes of her girlhood, giddy and free, and also the more domestic hopes of her young womanhood as a new bride and mother. Now, Lucille could see, the weight of seven people pressed heavily on her shoulders. Every morsel of food that passed their lips came from her labor. What if she should get sick? The loss of only a few days’ income would be enough to put them on the streets and cast them all, particularly the girls, into a degradation from which there would be no escape.

Every second of every day, this fear hid in her mother’s eyes. Yet there was still, Lucille could see, an almost childlike hope, little more than a wish made on a lucky clover, that things might change. What Lucille wouldn’t do to feed that tiny hopeful spark in her mother’s breast until it burst into a flame that would engulf all their wretchedness and poverty!

Lucille’s dreams were undoubtedly fresher than her mother’s, but to her they seemed no more possible. What could she, a sixteen-year-old girl with no skills and hardly any education, do to save her family?

“Skedaddle!” Her mother sighed again and gave her a pat on the rump, sending her out into the world.

And so, feeling guiltily relieved, Lucille left, stepping over a familiar drunk in the hallway, skirting half-naked children on the stoop, and ignoring the wolf whistle.

But I have to get ahead, somehow, she thought desperately. Ahead, and out, away from this filth.

On that evening Lucille would have done anything to escape her situation—if only she’d known how. . . .

Then she saw what she saw, that terrible thing—and did what she did, that terrible thing—and her entire life changed.

Product Details

- Publisher: Atheneum Books for Young Readers (June 13, 2017)

- Length: 352 pages

- ISBN13: 9781481447881

- Grades: 9 and up

- Ages: 14 and up

- Lexile ® HL790L The Lexile reading levels have been certified by the Lexile developer, MetaMetrics®

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

“Cinematic pacing, a compelling whodunit, and the glitzy aura of golden age Hollywood combine in this star-studded novel. . . . The authors’ knack for snappy dialogue is just the tops.”

– Booklist

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Girl about Town Trade Paperback 9781481447881

- Author Photo (jpg): Adam Shankman Photograph by Frank Meli(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit

- Author Photo (jpg): Laura L. Sullivan Photograph by Andy DeLay(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit