Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

LIST PRICE $16.99

Get 30% off hardcovers with code MOM30, plus free shipping on orders of $40 or more. Terms apply.

Buy from Other Retailers

Table of Contents

About The Book

Twelve-year-old Eva DeHart knows her family’s farm is the best, most magical place in the whole world. The Farm has apple trees and sun daisies and a creek. The Farm has frightening things too—like cougars, bears, and a dead tree that Eva calls the Demon Snag. And everything at the Farm shoots out of Eva’s fingertips into her poems. She dreams of being a heroine of shining deeds, but who ever heard of a heroine-poet?

When a blight strikes the orchard and a letter from the bank arrives marked FORECLOSURE, Eva is given that very chance as she puts all the power of her imagination at work to save the Farm. From a booth at the farmer’s market to the snowbound hills where the coyotes hunt, Eva discovers that we face our fears and find our courage in the most unexpected places.

This novel by acclaimed author Dia Calhoun is about the transforming powers of imagination and hope, which can turn us all into heroes.

Excerpt

On top of the hill,

I lean against the deer fence

and write a poem in the sky.

My fingertip traces each word

on the sunlit blue—

the sky will hold the words for me

until I get the chance

to write them down.

After the last line,

I sign my name—

Eva of the Farm.

My real name is Evangeline

after the heroine

in an old poem—

Evangeline: A Tale of Acadie.

Even though I’m only twelve,

I dream of being a heroine

of shining deeds—

like Saint Joan of Arc

or Meg from A Wrinkle in Time,

but everyone just calls me Eva.

Dodging the sagebrush on the hill,

I walk on

beside the wire deer fence

that protects our farm.

My job is to check for holes

the deer may have dug

beneath the wire.

It takes an hour and a half

to walk all the way around the deer fence—

our land covers nearly a hundred acres.

Our farm is named Acadia Orchard

after the land in the old poem.

You’d think we grow ambrosia,

or something magical for gods and heroes,

but we only grow plain old apples and pears—

Galas and Anjous—

here in the Methow Valley

in Eastern Washington.

I like those words—

something magical for gods and heroes—

and stop to write them in the sky

so I won’t forget.

I want to be a poet

with a shining imagination,

but whoever heard of a heroine-poet?

There’s nothing heroic

about scribbling stuff

that nobody wants to read—

except maybe my mom,

who is crazy mad about poetry

and Greek mythology.

I don’t show anybody

but Mom

my poems—

not my teachers,

not my friends,

definitely not my dad,

who thinks poetry is useless

because it can’t save the world

from all its problems.

Before Grandma Helen died,

I shared all my poems with her—

sometimes she’d even help me

find the perfect word.

She wanted me to enter my poem

“Waking up at the Farm in Summer”

in a national poetry contest for kids,

but I couldn’t bear the thought

of some stranger judging my poem

and stamping on it

with his big black boot.

Waking Up at the Farm in Summer

I wake

under a skylight

that shouts blue against my glad eyes.

Another sunny summer day!

I scurry

down the ladder from my bedroom loft

to the smell of Dad’s blueberry pancakes

sizzling in the frying pan.

I grin

at our black Lab, Sirius,

with a Frisbee in his mouth—

waiting for the first toss of the morning.

I run

outside with the gray squirrels,

the deer, rabbits, and whip-poor-wills—

high-fiving the newborn world.

As I walk down the hill,

checking the last section

of the deer fence,

dust dances around my feet.

It is hot and dry up here.

I can see my house below,

rising like a wooden ship

in a sea of green lawn.

I can see the orchard,

ruffled with leaves.

I can see the white slash

of the hammock.

I can also see that the west gate

leading to the wild canyon

stands wide open.

In my head I hear Mom shout,

“Close the gate!”

That’s the Golden Rule of the Farm:

Close the gates to keep

the deer out of the orchard.

Five gates stand guard

in the deer fence.

The east gate—

where we drive in from the highway.

The west gate—

where we hike up to the wild canyon.

The south gate—

where I go to play with Mr. Reed’s dog.

The north gate—

where we pick wild asparagus in the Andersons’ orchard.

And the fairy gate—

only three feet high, it leads to the old cherry tree

on the farm where my best friend Chloe used to live.

I think all these gates are chimeras—

that’s a word from the Greeks

that I learned in a book today

while reading in the hammock.

It means figments of your imagination.

Because if something really wants

to get into the orchard,

it will find a way through the gates,

through the deer fence.

I’m happy there is such

determination

in the world.

Sometimes, I want to fling all the gates wide open

to see what might come in.

Unicorns? Dragons? Centaurs?

Maybe then we’d get a little excitement around here.

Even Dad, who, in my humble opinion,

doesn’t have much imagination at all,

might like to see a unicorn eating apples

by the hammock.

After closing the west gate,

I slide into the hammock,

swing and swing,

and remember the poem

I wrote yesterday.

Hammock Queen

In the hammock

I am a queen

in a swinging throne of string

borne by two tall knights—

the maple trees.

I toss dried corn

to my grateful subjects—

gray squirrels who peer

and chatter at me,

paying homage.

On my right stands

the boundary of my kingdom—

the tall deer fence.

Beyond it the wild world

of the canyon threatens—

beckons—

riddled with dragons,

promises of shining treasure,

and perilous quests.

But here,

on my side of the fence, is the Farm—

with rows of apple trees

lined up like soldiers.

Here, in a throne of string,

beside the wild world,

I sway,

stricken to the heart with earth and sky,

knowing,

I belong to this, my apple kingdom.

A wet nose nudges my arm

just as my eyes flutter closed

in the hammock.

“Hello, Sirius,” I say to our black Lab.

I rub his ears,

silky as the yarn Grandma Helen spun

on her spinning wheel.

“You are a good and noble dog, Sirius,” I say.

His tail thumps on the grass.

I jump out of the hammock.

Mom and Dad will be waiting

for my report on the deer fence.

With Sirius following,

I cross the yard,

passing the vegetable garden,

passing the blue spruce trees,

their branches fluttering with quail.

I walk toward the big new shed

that we built last spring

for the farm equipment, shop,

and office upstairs.

Sirius trots behind me

through the door to the shop

where Dad kneels beside our new tractor,

changing the oil.

I remember picking out the shiny orange tractor

with Mom last spring,

remember being astonished by the prices

on the dangling tags.

“Look at all those zeros,” I’d said. “Do we

really have that much money?”

“No,” Mom had said. “But the bank does.

We’re taking out a loan to buy the tractor

and build the new shed.”

Dad, still kneeling beside the tractor,

looks at the oil dripping into the pan.

“At least this new tractor

doesn’t burn oil like the old one.

That’s one more thing we’ve done

to help save the environment.”

He pushes up his round, gold-rimmed glasses,

which are always sliding down his nose.

Mom, who is fixing a sprinkler valve,

glances up at me and asks,

“How is the deer fence?”

“No holes,” I say. “The deer fence is strong.”

“Good,” Dad says.

Mom and Dad work the Farm together,

but they’re always looking for ways

to make more money—

especially now that the economy

is bad,

and our neighbors—the Quetzals—

lost their farm.

Chloe Quetzal, my best friend,

had to move far away

over the lonely mountains

to Seattle.

I can’t imagine losing our farm,

or moving to the city.

To make extra money,

Dad guides white-water rafters

on the Methow River in the summer

and teaches skiing during the winter.

Mom writes fishing, hunting,

and gardening articles

for magazines.

She hunts in fall and winter.

So we eat venison and

duck,

duck,

duck,

and more duck,

and quail and grouse, too.

My brother, Achilles—

named, what a surprise,

after the Greek hero Achilles—

chews on a plastic ring

in his playpen in the shop.

When I pick him up,

he raises his chubby arms,

grabs my nose,

and grins his lopsided grin.

A nine-month-old baby,

he mostly howls and poops.

He’s cute when he is sleeping,

which doesn’t happen often enough,

in my humble opinion—

Grandma Helen used to say

“in my humble opinion”

all the time.

I leave the shed,

go into the house,

and climb the ladder to my loft bedroom—

a fancy way of saying attic.

I call it the Crow’s Nest.

With the skylight flung open,

I look at the sky—

it still holds the poem

I wrote up on the hill

by the deer fence.

To retrieve the words,

I stand still,

so still,

watching,

waiting,

until—

I am blueness,

I am cloud,

I am wind—

I am the sky.

Then the words of my poem

come flying back to me.

They are warm,

as though sprinkled

with all the spices of the sky.

When the poem is all inside my head again,

I write it down

in my best calligraphy.

I write all my poems

in calligraphy in black ink

on white Canson calligraphy paper.

Grandma Helen taught me

to shape the graceful letters

and hold the pen lightly

at a constant angle

in spite of my being left-handed.

I love the whisper of the pen

on the paper.

It makes me remember Grandma Helen.

The Haunted Outhouse

Grandma Helen built

an outhouse with a view

of the sagebrush hills.

“Sitting pretty,” she called it.

“Why not?”

She slapped white paint

on the boards,

carved a smiling moon

on the door,

and planted violets

on every side.

Last year, Grandma Helen died.

Now the outhouse door creaks

in the lonely wind.

The metal roof rusts

in the weeds

on the ground.

But sometimes,

in the moonlight,

through glimmering spiderwebs,

I think I glimpse

Grandma’s ghost—

sitting pretty.

Early the next morning,

I walk up the canyon with Dad.

The canyon winds like a green snake

between the dry sagebrush hills

behind the Farm.

Up and up and up we go—

looking toward Heaven’s Gate Mountain.

The canyon is beautiful.

Aspens—black-and-white Dalmatian trees—

and ponderosa pines

sway in groves

with the on-again-off-again creek

chanting through

like a prayer.

Quail skitter in the brush

and deer graze.

The canyon is dangerous, too.

Cougars, bobcats, and bears

prowl here sometimes,

so I am scared to go up alone,

scared to go through that gate

in the deer fence.

So I go with Dad,

who loves wild places

and wants to save them all.

As we walk along the creek,

I think about dryads and naiads—

those Greek spirits of wood and stream,

like Pan—

and wonder if the Farm and canyon

have spirits too.

I wish I could ask Chloe

what she thinks.

Before Chloe moved away,

we explored the canyon together.

She filled her sketchbook

with pencil drawings

of flowers, leaves, birds, and bugs.

Once she even drew a dead rattlesnake.

Me—I can’t draw to save my life.

Chloe knows all the common names

of every plant and insect,

and all their Latin names, too.

I haven’t seen Chloe

for five long months,

but we’ll be together again in

six weeks,

two days,

and ten hours—

for summer camp in Mazama in August.

We’ve gone to Camp Laughing Waters

every year since we were five.

When Dad and I reach

the first meadow in the canyon,

we find a half-eaten deer

sprawled across the trail.

Her throat is a bloody gash

torn by hungry teeth.

A sour stink already rises

from her guts

savaged across the dirt.

“Wow!” Dad exclaims, pointing.

“Look at the baby deer in the womb.”

On the ground

lies a blob

as white and transparent as tapioca pudding.

Inside, pokes

the delicate hoof

and head

of the baby fawn—

dead.

Sickened, I turn away,

glad Dad didn’t bring Achilles

as he sometimes does,

in the baby backpack.

“Coyotes killed this deer,” Dad says,

“or maybe a cougar.

We’ve scared them away

from their breakfast.”

I spin around

searching for the gleam of wild gold eyes

in the brush.

“I know this is brutal, Eva,” Dad says,

scanning the ground for prints,

“but that cougar or coyote has its own babies

to feed.

It’s just the wheel of life, turning.”

I scan the bowl of hills and say,

“Let’s go home.”

On the crest of the south hill

a black snag—

the tall, spiky stump of a dead tree—

points at the sky.

Lightning must have struck it

during a storm long ago.

Suddenly I see that storm

in my imagination:

A hundred lightning bolts

fracture the sky

into a skeleton of light.

One bolt strikes the tree—

it stands—

trembling,

crackling,

absorbing

unimaginable power.

I blink,

and now I see that the black snag

looks like someone

wearing a black robe with a hood.

My skin creeps and crawls—

the stink of the dead deer

rising around me—

because I know,

just know,

that black snag has a powerful evil spirit.

One branch with a knob on the end

thrusts out like an arm

holding a black ball.

And it points straight at me.

The Demon Snag

Halfway up the canyon

the blackened snag on the hill

looms like a demon,

conjuring and cackling

evil dreams of the wild—

cougar teeth and bear claws and being eaten alive—

until fear cripples my heart.

I sharpen Dad’s ax—

but a demon felled would be a demon still.

I call for a wizard,

but they are too busy fighting dragons.

If I were Joan of Arc,

I could defeat the Demon Snag myself

with a shining sword.

But I am only Eva of the Farm,

armed with a shining imagination

that makes me run home fast.

I send Chloe an e-mail

about the dead deer and her baby.

For two long days I wait for an answer

from Seattle.

Finally Chloe replies,

“Don’t send any more disgusting messages like that!”

I slump,

drop the half-eaten apple in my hand,

and stare at the computer screen

in the Crow’s Nest.

The Chloe I know

would have dissected that dead deer.

The Chloe I know

would have whipped out her sketchbook

and drawn a hundred pictures of that dead deer.

The Chloe I know

is an explorer and mastermind of daring deeds.

Now she only sends one-sentence e-mails.

The screensaver flashes—

a picture of Chloe and me

standing by a canoe

at Camp Laughing Waters.

Chloe’s long, curly blond hair—

princess hair—

blows in the wind,

mixing with my lank

red-brown hair.

Wreaths of wildflowers

crown our heads.

The picture looks like a scene

from a fairy tale.

I put one hand to my side.

Tucked beneath my ribs

is the jagged hole

from losing Grandma Helen—

frayed and sore around the edges.

Now Chloe stands on the edge

of that hole—

about to fall in,

about to rip it wider,

about to vanish forever too.

“Don’t go away, Chloe,” I whisper.

“Don’t go away like Grandma Helen did.”

But Chloe doesn’t look at me,

doesn’t hear me,

she only keeps smiling on the screensaver

with her hair blowing in the wind.

I sigh and turn away from the computer.

Heat grips the walls of the Crow’s Nest.

I’m so hot you could fry an egg

on my forehead,

as Grandma Helen used to say.

The Crow’s Nest is the hottest room in the house

in summer

and the coldest one

in winter.

I swing the skylight open

on the slanted wall

over my bed

and hope for a breeze

to come skipping in,

and one does—

a breeze so fierce

my sun hat

sails off the doorknob.

Outside, storm clouds bully Heaven’s Gate Mountain

heading for the Farm.

I love the Crow’s Nest when the wind

shrieks around the eaves.

It makes me think of Meg

from A Wrinkle in Time

shivering in her attic,

waiting for Mrs. Whatsit,

Mrs. Who, and Mrs. Which.

I climb down the ladder to find Achilles

to watch the storm with me.

He always laughs at thunder and lightning,

as a proper Greek hero should.

Mom sits huddled at the kitchen table

staring down at Grandma Helen’s gold watch

in her hands.

Twelve emeralds—

twelve for the months of the year,

green for the Farm, Grandma Helen used to say—

sparkle around the watch face.

“Mom?” I ask.

She doesn’t look up.

“Mom, what’s wrong?”

Mom answers in a choked voice,

“Grandma Helen’s watch stopped.”

“Did you wind it?” I ask.

“Of course,” she says. “It stopped.

Just . . .

stopped.”

Her face locks up as tight

as a turtle in its shell—

she’s trying not to cry.

My great-grandmother Nita

gave Grandma Helen that watch.

Just before she died,

Grandma Helen gave it to Mom.

Someday, Mom will pass it on to me.

She lets me wear the watch

on my birthday.

“Can’t we get it fixed?” I ask.

Mom doesn’t answer,

but tears fall down her face.

I run outside to find Dad.

He’s not in the shop in the shed.

So I climb the stairs to the office

where Dad’s computer hums.

A “Stop Global Warming” slide show

Dad made plays on the screen.

One slide says “No Farms No Food.”

The next slide shows the Farm in spring,

the next, the Farm in summer—

and on through the rest of the seasons.

On the last slide, a polar bear

stands beside a melting glacier.

Where is Dad?

He could be anywhere.

Grandma Helen used to say

that when Dad got up in the morning

he hit the ground running.

He seems even busier since she died.

As the slide show repeats,

I guess where Dad is.

And I do find him,

outside in the tree nursery—

a garden where he plants

baby evergreen trees in brave rows.

When they grow big enough,

he transplants them around the Farm.

The branches on the baby trees dance

in the rebellious wind.

Dad plunks one little ponderosa pine

into the wheelbarrow.

“Where are you going to plant that one?” I ask.

“By the canyon gate,” he says.

Then he adds, as I know he will,

“Plant a forest, save a polar bear.

Want to help?”

I shake my head. “A big storm’s coming.”

Dad looks up toward the black clouds

quilting Heaven’s Gate Mountain.

“I hadn’t noticed,” he says.

“Mom’s crying,” I tell him,

“because Grandma Helen’s watch stopped.”

Dad frowns.

I add, “I think she’s missing Grandma Helen again.”

“She’s always missing Grandma Helen,” Dad says.

“It’s been a year. I don’t . . .”

His face sags. “I just don’t know what to do anymore.”

And he trundles the wheelbarrow away,

not toward the house,

but toward the canyon gate—

into the storm.

Summer Storm

Above Heaven’s Gate Mountain

the wind curls

over the hot blue sun.

Across the hills

the pine trees roar—

sparkling, black-veined emeralds.

Deep in his den

the coyote shivers,

knowing there will soon be thunder.

Up the canyon

the aspens shimmy in the rain

pelting their white bark.

Along the deer fence

the beans snap,

and the corn careens across the garden.

In the sky

clouds ponderous as melons

begin their slow black calling.

From my skylight

I see the flash of a meadowlark

singing the bright memory of sunlight.

Achilles claps his hands

and croons when the storm

flings jagged pearls of hail

against the skylight.

When the hail finally stops,

rain parades

against the glass

on

and on

and on

while the robins

hop over the wet grass

and stuff their beaks

with worms.

So I build a block castle

for Achilles.

I plop his toy horse inside the castle walls

and tell him the Greek story

of the Trojan horse.

Achilles listens,

his eyes as big as robin’s eggs,

as though he really understands.

At just the right moment in the story—

when the Greeks are sneaking out of the horse

to destroy the city of Troy—

Achilles reaches out with both hands

and knocks down the castle

I have so carefully built.

He shrieks and gurgles with glee.

“You’re a true Greek hero, Achilles,”

I say, laughing.

When at last the rain stops,

the desert heat prowls

across the land again.

I’m glad we have a good well.

I’m glad the Methow River runs nearby.

Most of all,

I’m glad for the irrigation sprinklers.

Sprinklers

In this desert land

arcs of water—

silver rainbows—

pulse from a thousand sprinklers

day and night,

sweeping circles

around the apple and pear trees.

In this desert land

the apple and pear trees

are always thirsty,

always hot,

their wet green leaves

taunting the dry hills—

“nyah, nyah, na-nyah-nyah!”

In this desert land

if I am thirsty,

if I am hot,

I dance and drink

and grow dizzy

running through

the sprinklers.

In this desert land,

the water comes

from the Methow River—

so I think there should be fish

shooting out of the sprinklers

and into Dad’s frying pan

for dinner.

A week later,

I walk out to the shed,

looking for Mom and Dad,

to tell them about

a pear tree with dead

leaves on one of its branches.

No one’s in the shop.

Tools hang in orderly rows

from hooks on the walls—

saws, axes, hammers, wrenches,

coils of rope,

and a dozen pruning shears.

In one corner,

a blue sheet shrouds

what I know is Grandma Helen’s spinning wheel.

It broke a month before

she got sick.

Mom hauled it into the shop,

planning to fix it.

But she hasn’t touched the spinning wheel,

even though I’ve told her a hundred times

that I’d love to learn to spin,

like the three Fates in Greek mythology.

Dust rises

when I lift the blue sheet.

The spinning wheel is beautiful.

It should be turning,

should be spinning,

shouldn’t have cobwebs

tangled in the spokes.

I used to write my best poems

to the sound of the wheel humming

while Grandma Helen spun.

Footsteps crunch in the gravel

outside the shop door.

The door creaks open

and Dad strides in,

his face grim.

“What’s wrong?” I ask.

“Fire blight,” he says.

My breath shoots into my lungs

as I remember the pear tree with dead leaves.

“How bad?” I ask.

“Terrible,” he says.

He explains that

last week’s hailstorm

gouged the bark on the pear trees.

More days of heat and rain

brought fire blight,

a horrible disease,

I know,

which might destroy

our entire pear orchard.

“I saw a pear tree

with a dead branch,”

I say.

“Where?” he asks.

“Down by the fairy gate.”

Dad becomes a whirlwind,

pulling saws and axes

off their hooks on the wall.

“Then it’s spread even farther

than I thought,” he says.

“Looks like were in for a siege.”

The Siege

Mom’s saw, screeching.

Dad’s ax, hewing.

My heart, aching.

Hour after hour,

day after day,

I pile dead branches

into the wheelbarrow

and trundle them

to the bonfire.

Only butchery

and burning

will keep the disease

from spreading

and stop

the fire blight—

maybe.

Our orchard

curls up in smoke

that stings tears

into my eyes

as I say good-bye

to my lost friends

the trees.

One night at dinner Dad says,

“The pear crop is mostly gone,

but we still have the apples.”

His eyes are bloodshot from smoke.

“The Galas weren’t touched by the blight.”

But I know

we have only ten acres of apples.

I know

Mom and Dad borrowed all that money

for a loan from the bank

to buy the new tractor

and build the new shed.

I don’t know

how we will pay the bank back.

I don’t know

what we will do.

I don’t ask,

but think of the Demon Snag

up the canyon

and wonder

if its evil power

caused the fire blight.

“The Gala crop is good,” Dad says into the silence.

I stare down at the scrambled eggs

speckling my blue plate

for the fourth time this week.

“I’m tired of eggs,” I say.

“Would you rather have duck?” Dad asks.

I shut right up.

“Have you finished your new poem

about the fire blight?” Mom asks me.

Dad frowns. “You should ask

if she’s finished her summer math homework.”

I hunch my shoulders,

sensing one of Dad’s lectures,

and, sure enough, it comes.

“You’re such a bright girl, Eva,” he begins,

pushing up his gold-rimmed glasses.

“Your generation is facing so many problems—

like global warming

and species extinction.

You can’t feed a poem

to a starving polar bear.

You can’t use a poem

to stop tiger poaching.

The answers lie in math and science

and economics—

not poetry.”

I’ve heard all this before,

but still something shrivels inside me

like a slug

when you pour salt on it.

Mom says, “Words can move hearts, Kurt.

A poem about the plight of the polar bears

might inspire people to help them.

We make the most difference

when we use the gifts we have.

And Eva is a gifted poet.”

Dad’s face softens.

“Of course she is,” he says. “I just want you

to be a well-rounded person, Eva,

so you can take on the world

when you grow up—

and make a decent living.

I’m betting your average mathematician

earns more

than even a gifted poet.”

I swallow a big bite of eggs

and say to defend myself,

“I have finished my summer math homework.”

Mom changes the subject.

“Summer is half over.

“Tomorrow we’ll go to the thrift shop in Twisp

to buy you new school clothes.”

“And camp clothes, too,” I say.

“I need new shorts.”

Mom and Dad glance at each other,

Mom starts to speak,

but just then Achilles flings

his plate of eggs onto the floor.

I finger the hole in my shorts.

The clothes from the thrift shop won’t be new,

but other people’s hand-me-downs.

I like the thrift shop, though,

because anything is possible there.

Anything Is Possible

For three dollars

anything is possible at the thrift shop

at the Senior Center in Twisp.

For three dollars

you can stuff whatever you want in a bag.

The thrift shop has everything

you can imagine

and some things you cannot.

Clothes, dishes, toys, puzzles—

Mom can stuff a bag tighter

than our Thanksgiving turkey.

It’s embarrassing.

For three dollars

I can stuff a new me

into the bag.

I can become a heroine

in a flowing red skirt

with only a little tear

that trails behind me on the floor—

and a ruffled white shirt

like Evangeline might wear.

I add silver boots and a silver helmet

with only a small dent,

like Joan of Arc might wear.

And I am ready for anything.

Three dollars

is too much for me to waste,

Mom says.

She dumps everything out of my bag

except the silver boots,

which I can wear in the snow.

She crams the bag with boring

T-shirts, jeans, and sweaters.

If Joan of Arc’s mother

and Evangeline’s mother

and Meg’s mother

were anything like mine,

they would never

have had any adventures at all.

Tonight there will be a meteor shower

called the Perseids.

It happens every August

in the constellation of Perseus.

Everyone—

Dad, Mom, Achilles, Sirius, and me—

lies outside on the grass,

listening to the cricket symphony

and waiting for the shooting star show

to begin,

as we have every year

for as long as I can remember.

This year I’m especially excited,

because this is Achilles’s first time

to watch the Perseids.

I want him to see

his first falling star—

his blue eyes opening wide in delight.

I want him to stretch

his hands toward the stars.

For a few hours I can forget

about the fire blight’s rampage,

about Chloe’s silence,

about Mom’s grief,

about Dad’s indifference,

about Demon Snags.

Forget.

As darkness falls,

I think about my last e-mail to Chloe.

I told her about the fire blight,

but she hasn’t answered.

Not one sentence.

“I wish Chloe were here to watch

the show with us,” I say to Mom and Dad.

“But at least I’ll get to see her soon

at Camp Laughing Waters.

I can’t wait!”

Mom and Dad exchange glances.

“Eva,” Dad begins, but Mom interrupts.

“This isn’t the best time to tell her, Kurt.”

But Dad shakes his head. “There’s no good time.”

I sit straight up. “Tell me what?”

Mom’s face is serious. “I’m afraid

there will be no summer camp this year.”

My hands clutch the grass

as though I might fall off the world

if I don’t hold on tight.

“What do you mean?” I ask. “Why?

Did the camp close?”

Dad sighs. “No. We just can’t afford

to send you this year, Eva.

You know how bad things are—

with the fire blight ruining the pear crop.

Money is tight.”

“Very tight,” Mom adds.

“But”—my voice squeaks—

“I was going to see Chloe again.”

Mom says, “Mrs. Quetzal called me yesterday.

Chloe isn’t going to camp this year either.

She doesn’t want to go.”

My fingers claw even deeper

into the grass

as I say in a faint voice, “She doesn’t . . .

want to go? Why not?”

“Sometimes,” Mom explains gently,

“when people move away and begin new lives,

they also make new friends

and find new interests.

I think Chloe’s done that.

I am so sorry, Eva.”

“There!” Dad shouts. “I see a falling star!”

But I do not look up.

I fall back on the grass

and squeeze my eyes shut—

squeeze my fists shut—

squeeze my worry shut

tightest of all.

Falling Star

Falling

I shoot—

falling

I shine—

falling

I vanish

forever.

Cherries are my idea of heaven,

but we don’t have a cherry tree.

We used to pick buckets from the tree

in Chloe’s orchard

on the other side of the fairy gate.

Our new neighbors

haven’t offered us any cherries,

and we don’t have money to buy them—

cherries are expensive,

even at the farmer’s market in Twisp.

Sometimes I think if I could taste

one cherry—just one—

the worry inside me

would go away,

and everything would be all right again,

and I could go to Camp Laughing Waters

with Chloe.

Cherries are that magical.

The Old Cherry Tree

A ladder sighs

against the old cherry tree

across the deer fence

in the neighbor’s yard.

Cherries dangle

like ruby earrings

from the branches.

In spite of Mom’s warnings,

I want to steal those cherries

and stuff them in my mouth.

The cherries taunt

beyond my outstretched fingers

while starlings jeer and dart,

pecking greedy holes in the fruit.

I long for thieving wings—

to steal such sweetness for myself.

On Friday morning

Mom and I drive to the post office

in Methow—

a town so small

a rabbit could pass it by

in one hop.

Mom leaves our old Ford truck running

while I go in and grab the mail

from our post office box.

I flip though the stack and find

—a flyer for a free pizza,

if you buy three large ones

at the regular price

—a letter from Dad’s cousin in Seattle

—a copy of the Good Fruit Grower magazine

—a letter from the Methow Valley Community Bank

with big red letters printed on the envelope:

URGENT: FORECLOSURE NOTICE.

The envelope is as white as snow,

and a chill spreads from it

up through my fingers.

I’ve heard the word

“foreclosure,” somewhere before.

Although I scrunch up my brain,

and think and think,

I can’t remember where.

I put the letter from the bank

on top of the pile of mail

so Mom will see it right away.

I will ask her

what foreclosure means.

But when I climb back into the truck

and Mom sees the letter,

her face turns pale.

She snatches the letter,

stuffs it into her purse,

and then hunches over the steering wheel,

her pink lips pressed tight.

My breath speeds up,

coming short and fast.

My tongue sticks

to the roof of my mouth

as though I’ve eaten

a whole jar of peanut butter.

I’m too afraid to ask Mom

what foreclosure means.

Something is wrong—

terribly wrong.

When we get home,

I climb straight up to the Crow’s Nest,

sit down at my computer,

and Google “foreclosure definition.”

This is what comes up:

“Foreclosure is a legal proceeding

where the bank takes possession

of a mortgaged property

when the borrower is behind

on loan payments.”

A hot nail seems to scrape

down my spine as I slump in my chair.

What I have been afraid of

since the fire blight struck

is true.

What I have been too scared

to think of—

except in the cobwebby corners

of my imagination—

is true.

No.

Don’t say it.

Mom and Dad will not let anything bad happen.

But I remember Mom’s pale face

as she snatched the letter.

I have to know what this all means.

I have to.

Mom and Dad are so busy

talking by the zucchini plant

in the vegetable garden

that they don’t hear me coming.

Mom paces with Achilles on her hip.

“My family has been banking

at that bank for thirty-two years,” she says.

“You’d think Charlie would have

the guts to come say this to our faces

instead of sending a form letter.”

Dad, cutting a bat-size zucchini

from its stalk,

glances up and sees me.

“Claire,” he says in a warning voice to Mom.

She turns,

sees me too,

and puts a smile on her face.

“Why, Eva,” she says.

I open my mouth,

close it,

then open it again and say,

“I just Googled foreclosure.”

Mom’s smile fades.

Dad stands up with the zucchini in his hand.

“I’m sorry, honey,” he says. “We didn’t mean

for you to find out that way.”

“So it’s true?” I ask. “We’re behind

on paying back the loan

to the bank?”

Mom and Dad both nod.

I try to swallow

but can’t.

I try to speak

but can’t.

Achilles stretches out his arms toward me,

and I take him from Mom.

With my face buried in his short brown curls

I say at last,

“What does all this mean?”

“It means,” Mom explains,

that we could lose the Farm.”

Everything seems to stop:

The wind stops blowing—

the birds in the blue spruce stop singing—

the river stops roaring—

the garden stops growing—

and the Farm itself

seems to heave a great sigh

because the words are out,

are spoken at last—

lose the Farm.

This farm has been in Mom’s family

since Grandma Helen was a girl.

Mom grew up here.

I want to grow up here.

Achilles wants to grow up here too.

I hug him tight

against the ache in my chest.

Achilles reaches up,

pats my wet cheek,

and says, “Va.”

Mom, Dad, and I all stare at him.

“What did you say, Achilles?” I ask.

“Did you try to say Eva?”

He beams. “Va!”

I cry harder.

Achilles has spoken his first word—

my name.

I whirl him around

again and again.

I will never lose Achilles.

First Word

Like a butterfly

from a cocoon,

the word

from his lips

changes

a baby

into

a brother.

Dad starts doing odd jobs—

when he can find them,

but they don’t pay much.

Mom gets a new job,

waitressing in the Methow Café

on Thursday, Friday, and Saturday nights

to bring in more money.

That’s all she can find.

And lucky to have it, she says,

because so many people

are out of work right now.

She says she will

write more articles,

but editors are picky,

she claims.

The truth is,

Mom hasn’t sold one word—

not

one

word

since Grandma Helen died.

Me, I can’t think of one thing

a twelve-year-old can do

to earn money.

So I feel pretty much worthless.

All I can do is look after Achilles

while Mom and Dad work.

But that doesn’t bring in one cent,

unless Achilles starts pooping gold.

I leaf through my stack of poems,

written in my best chancery cursive calligraphy.

Poets are always poor—

unless they become poet laureates

or write greeting cards

or advertising slogans.

Maybe Dad is right.

Maybe I am wasting my time on poetry.

But I don’t see how math or science

will save the Farm either.

I take out a blank sheet

of Canson calligraphy paper,

then hesitate.

Mom says when I use up

the last of my calligraphy paper,

there will be no money for more.

So I need to be sparing.

How can I be sparing with poetry?

Same Old Bear

Wood crackles the dawn,

and I know the same old bear is feasting

in the same old plum tree again.

Every year he swipes off whole branches,

gorging on glistening plums.

Does he dream of plundering our orchard

all winter in his stuffy den?

The tree looks worse every year—

mauled and broken—

but keeps bearing plums

as fat and red as a baby’s cheeks.

The bear looks worse every year too—

muzzle gray, fur matted, one ear missing—

but keeps looting.

I keep expecting one of them to die—

the tree or the bear—

but they seem to need each other.

Which just goes to show you

that sometimes things work out fine

for everybody.

So long as that old bear

leaves a few plums for me.

Swinging in the hammock,

I look out over the orchard,

over the house with its shining metal roof,

over the tangle of the vegetable garden.

Does the Farm know

we might have to leave?

Could the land

help us stay?

I look the other way

and stare through the deer fence

at the wild canyon.

Is the Demon Snag

causing all our troubles?

Is it summoning

powerful evil magic

that creeps down the canyon

and slips through

the chimera of the deer fence?

The canyon and the Farm

must have kindly spirits as well.

I think of Mrs. Whatsit,

Mrs. Who, and Mrs. Which—

kindly spirits of stars—

who helped Meg become a heroine

and fight the darkness

and save her little brother.

How can I fight

the Demon Snag?

What kindly spirits will help

me save the Farm?

I decide to walk up the canyon alone

to confront the Demon Snag.

Then I picture the deer with its

bloody throat

lying slaughtered across the trail.

I have no magic,

I am not wearing my silver boots,

it is almost dark—

and I am not even brave enough

to go up alone in the light.

I slip out of the hammock,

trudge up to the Crow’s Nest,

and fall asleep

with the skylight open.

Skylight at Night

Bats fly

like black ghosts

in and out

of the skylight

over my bed

at night.

Stars fly

like guardian angels

in and out

of the skylight

over my bed

at night.

Owls fly

like wizards

in and out

of the skylight

over my bed

at night.

Wishes fly

like whirling seeds

in and out

of the skylight

over my bed

at night.

Dreams fly

like magic carpets

in and out

of the skylight

over my bed

at night.

Sleeping deeply,

I remain.

The bank man

Mom calls Charlie

and I call Mr. Eyebrow

drives up our road this morning

to talk with Mom and Dad.

I don’t like the look of Mr. Eyebrow.

In spite of the heat,

he wears a black suit

with a dark gray tie—

like an undertaker.

One black eyebrow

crawls across his forehead.

He is as tall and thin

as the Demon Snag.

Mom and Dad and Mr. Eyebrow

talk inside the house for a long time.

I sit on the deck

with Achilles

but can’t hear a word.

Sirius curls beside us

as we watch heavy clouds gnaw the sky.

Achilles puts his hands on the railing

and pulls himself to his feet.

My hand hovers behind his back

in case he falls.

“We’ll probably have to move to Seattle,

like Chloe did,” I say to him.

“To some tiny horrible apartment.

You won’t grow up knowing the Farm.

You won’t know the orchard,

or harvest time,

or the deer,

or the old bear,

or the hammock,

or the gray squirrels,

or the garden,

or the sun daisies,

or Grandma Helen’s haunted outhouse.”

My stomach pushes

into my throat

until I almost throw up.

Grandma Helen never knew Achilles—

because she died

three months before he was born.

And now Achilles will never

really know Grandma Helen—

because he won’t know the Farm.

Achilles crawls into my lap.

He senses something is wrong.

I grab his hand and kiss each fingertip

until he laughs.

When Mr. Eyebrow comes out of the house—

his shiny black shoes

shaking the deck with every step—

I clutch Achilles tight,

as though the man might steal him away too.

Achilles squirms.

Mr. Eyebrow doesn’t say hi,

doesn’t even look at us.

Dad walks out on the deck, softly,

and watches Mr. Eyebrow drive away

in his shiny red BMW.

“Well?” I ask.

“Get your rod,” Dad says.

“We’re all going fishing.”

I cheer,

but Mom looks at Dad and sighs.

Fishing

I wait for a fish

from the deep

to rise

for my fly—

wait for something

from the deep

to rise

shining—

wait for anything

from the deep

to rise

to the light

and save us all.

On the way home from fishing,

we stop in Twisp for gas.

Through the truck window,

I watch people bustle around

the Twisp Farmer’s Market,

buying and selling crafts and produce.

One kid sits at a card table

with a red plastic pitcher

and a stack of Styrofoam cups leaning

like the Tower of Pisa.

A sign printed in crooked black letters reads:

LEMONADE, 50 CENTS A CUP.

I wish I could sell something too,

to earn money.

But all I have are my poems.

No.

I could never show the world my poems.

Besides, who would want

to buy them?

After we come home,

after we eat four fat rainbow trout

fried in flour, salt, and pepper for dinner,

Dad and Mom call a family meeting

around the kitchen table.

Even Achilles attends,

banging his spoon on his high chair.

“We have three months,” Mom says.

“Because we have been customers of the bank

for thirty-two years,

the bank is giving us

three extra months to catch up

before they start

foreclosure proceedings.

The Galas will bring in some money

when we pick them next month.”

“But probably not enough,” Dad says.

“We still need a miracle

in order to keep the Farm.”

Farm Miracles

A miracle—

that apple blossoms

turn into fruit.

A miracle—

that birds learn to fly

without any lessons.

A miracle—

that sun daisies

bloom gold every spring.

A miracle—

that poems

rise out of the land.

A miracle—

is easy for the Farm.

A miracle for us to stay.

All night long I toss and turn

under the open skylight.

Can I,

dare I,

try to sell my poems?

Pull my secret heart

out of my chest

and lay it on the table for everyone to see?

I have to do something—

something to help save the Farm.

I would rather have someone

scorn my poems,

or worse,

laugh at them,

than lose the Farm.

In the morning I tell Mom and Dad

I want to sell my poems

at the Twisp Farmer’s Market

next Saturday.

“Would a dollar a poem

be too much?” I ask.

“I think that sounds just right,” Mom says.

But Dad says, “Don’t get your hopes up

too high, Eva.”

While I wish

I could sell copies of my poems

written on Canson calligraphy paper,

I don’t have enough of that paper left.

So, over the next week,

I take the poems

I have already written out beautifully

and scan them into Dad’s computer in the office.

Then I print out copies

on colored paper—

sky blue,

butter yellow,

sage green,

and petal pink.

Achilles crawls around my feet

while I work.

I pick him up and give him

a big kiss.

“Maybe,” I tell him,

“I’ll make enough money

from my poetry that you can grow up

on the Farm after all.

Maybe poems can make a miracle.”

At the Twisp Farmer’s Market

Apricots, apples, and artichokes,

carrots, cabbages, and crafts,

jewelry, jam, and jelly,

photographs of the Methow Valley—

tables and tables of treasures

at the Twisp Farmer’s Market.

Sellers wait behind each table,

hoping the rich folks from Seattle

who have come to spend

the weekend in the country

will buy, buy, buy,

at the Twisp Farmer’s Market.

I write that poem

sitting at my card table

waiting for customers.

Rocks hold down

the neat stacks of poems

to keep them from blowing away

in the wind.

Taped to the front of the table is a sign

Mom made on the computer:

A DOLLAR A POEM—SUPPORT YOUR LOCAL POET.

I am the only poet

at the market,

so there is no competition,

Mom says.

Dad lets me wear his baseball hat

for luck.

I half hope no one will stop.

But people do stop, smile,

and ask if I’m the poet.

I nod.

When they read my poems,

sweat blooms on my forehead,

and I want to slink under

the card table

and vanish.

For the Farm, I think,

gripping the seat of my metal folding chair.

For the Farm.

No one makes fun of me.

But every time someone reads a poem

and walks away without buying one—

sometimes without even a comment—

I droop like a wilted sun daisy.

Then a farmer in a blue-and-white-striped shirt,

who is selling vegetables

at the table next to me,

reads “Same Old Bear” three times.

He chuckles—in a nice way.

“Well, I’ll be darned if I don’t have a bear

just like that,” he says. “But with me it’s apricots

instead of plums. My wife

will get a kick out of your poem.”

I stare at the dollar bill he hands me—

then smooth it through my fingers.

It is soft,

as though it has been through the wash

many times.

By noon, to my surprise,

I’ve sold all ten copies

of “The Haunted Outhouse,”

five copies of “Sprinklers,”

three copies of “Summer Storm,”

and six copies of “Same Old Bear.”

By the end of the afternoon

I’ve made thirty-four dollars—

thirty-four dollars!

I proudly give it all to Mom and Dad.

They’re surprised too,

especially Dad.

They give me back two dollars

to spend however I want.

I know exactly what I want.

I pass the candle maker’s table

with its colorful pillars and tapers.

I pass the jam maker’s table—

not even tempted

by the huckleberry preserves.

I pass belts,

pass fudge,

pass sausages,

pass lavender,

pass herbal wreaths,

pass inlaid boxes,

pass stained-glass windows.

At last

I reach the Bead Woman’s table.

Mysterious and beautiful,

the Bead Woman wears scarves

in water colors.

A turquoise-blue scarf sparkling with crystals

circles her dark brown hair.

A cerulean-blue scarf

drapes around her neck.

A navy-blue scarf

wraps around her hips.

She makes jewelry with polished stone beads

in sober colors—

green, brown, rose, gold, white, black.

Some are round, some square,

some speckled.

Each bead is different, magical—

handmade

like a stone poem.

There are pendants, necklaces, bracelets, earrings—

exactly the kind of jewelry I imagine

a heroine would wear

as she battles powerful

Demon Snags in the wild canyon.

“Do you have anything for two dollars?” I ask.

The Bead Woman sadly shakes her head no,

her hair swinging

down to her waist.

“Would you trade a poem

for a bead?” I ask.

She smiles. “So you’re the poet

everyone is talking about.”

I blush to hear that people are talking

about me.

“You like rocks,” I say.

“And I have a poem about a rock.

“Would you . . .” I take a deep breath.

“Would you like to read it?”

“I’d be honored,” she says.

Canyon Rock

I found you,

rock,

your face glinting red

in the morning sunlight,

on the path

winding up the canyon.

I hold you,

your edges

declaring your

ancient journeys.

I take you,

who risked all dangers

the moment you were no more a mountain.

Take you

to shape you to my hand—

as the wind did,

as the rain and glacier did,

until you make of my heart, too,

an offering,

for someone walking by

who catches the morning sunlight on my face

and stops.

The Bead Woman gazes up at me,

gazes through to the center

of me—

gazes

and gazes

until I look down.

Then she reads my poem out loud

while I roll my two dollar bills

into a tight cylinder.

“This is enchanting!” she exclaims.

“You are a savant with words.”

I ask, “What is a savant?”

She falls silent for a moment.

The sun sparks off the crystals

on the scarf in her hair,

and suddenly

she is crowned with a halo.

At last she says, “A savant is someone

with an extraordinary gift—

a gift that flows

directly from the great creative power

in the universe.

For this poem I will trade you

something special.”

She reaches into a basket by her feet

in their gold leather sandals,

and pulls out a silver cord

with a rose-colored stone pendant

in the shape of a circle

dangling on the end.

I draw in my breath—

the polished stone looks like a sunrise

caught on a necklace.

A narrow band of green runs through it.

“This stone is called thulite,” the Bead Woman says.

“It comes from right here in Eastern Washington

near Riverside.

The quarry is fiercely guarded

by rattlesnakes.

I give it to you

from one artist to another.”

“Can it defeat evil spirits?” I ask.

The Bead Woman looks at me for a long time.

Then she says, “The power of the stone mirrors

the power of your own imagination.”

Before I can ask her what she means,

another customer comes up—

a woman too dressed up

to be a local.

The Bead Woman gives me a little bow

and turns away.

When I slip the silver cord over my head,

the rose stone pendant

hangs over my heart.

I will wear it for the first day of school

on Monday.

About The Illustrator

Product Details

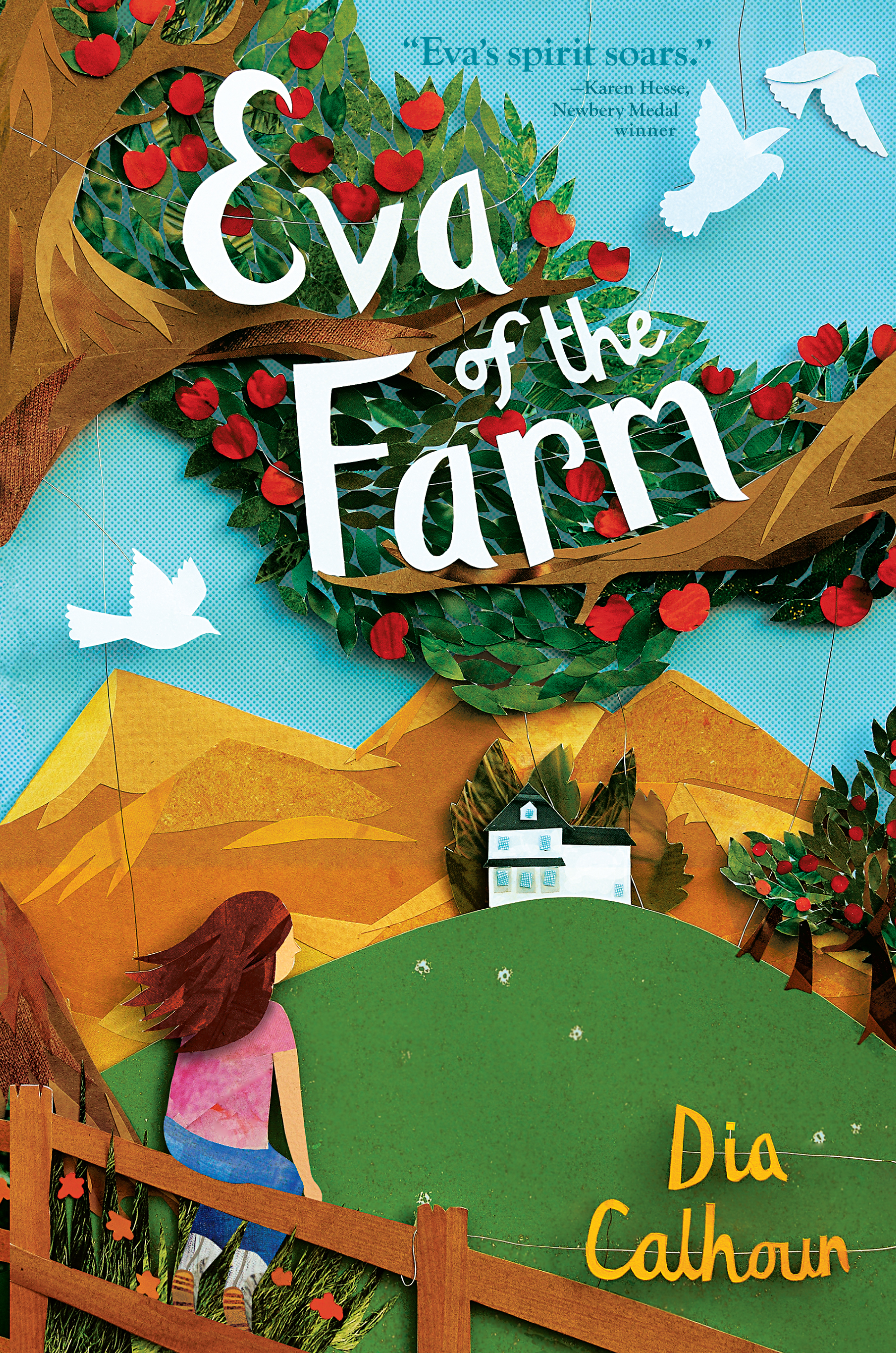

- Publisher: Atheneum Books for Young Readers (July 10, 2012)

- Length: 256 pages

- ISBN13: 9781442417007

- Grades: 4 - 7

- Ages: 9 - 12

- Lexile ® 840L The Lexile reading levels have been certified by the Lexile developer, MetaMetrics®

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

"Eva's spirit soars."--Newbery Medalist Karen Hesse

"Named after Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s heroine from his epic poem Evangeline, 12-year-old Eva lives on her family’s beloved Acadia Orchard in Eastern Washington. In this beautiful, tightly woven novel in verse, which follows the progression of the seasons, she may have to leave her idyllic home, just like her namesake. As Eva plucks words from the world around her—'They are warm, / as though sprinkled / with all the spices of the sky'—her 'plant a forest, save a polar bear' father only sees the value of math, science and economics. Their rift grows wider when a blight starts the ripples of foreclosure. Eva begins to blame their mounting misfortunes on a blackened tree in the canyon known as the Demon Snag and the evil it must be emitting. Forming a fierce bond with the local Bead Woman, who’s encountered her own tough times, the resilient girl not only discovers a kindred artist, but the power of imagination, hope and even poetry to save her farm—and spirit. Calhoun doesn’t shy away from Eva’s reality, offering snapshots of the cycle of life, including a baby deer ripped from its mother’s womb. Although Eva’s poetry far surpasses most experienced poets, the effect leaves readers with splendid images to savor.

Fans of Karen Hesse will welcome this partner in poetry."

--Kirkus Reviews, May 15, 2012

"The beautifully composed language slowly relays Eva’s journey through the realities of adult problems, and intuitive readers will appreciate the lyrical and metaphorical imagery. Collagelike illustrations introduce each section. This text offers much to prompt discussion and poetry writing."

–School Library Journal

Twelve-year-old Eva (Evangeline) loves her life on the family orchard in Washington State, loves her baby brother Achilles, and loves to write poetry. Indeed, writing poetry is Eva’s way of making sense of her world, as she writes about how much she misses her grandmother and her former best friend, Chloe, and how she worries that her family will lose their farm that, to her, is utterly magical. This last worry is not an idle one, as a events soon put Eva’s family in dire financial straits.

However, Eva’s poetry, a newfound adult friend, and Eva’s own strength bolster her through this difficult time, and although the story ends with the farm’s ownership still in limbo, there is a feeling of hope and possibility as well.... The potentially hopeful but ultimately unresolved ending is also refreshing, and kids who have also faced financial uncertainty may especially relate to Eva’s family’s plight.

Bulletin of the Center for Children's Books

Awards and Honors

- CBC Best Children's Books of the Year

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Eva of the Farm Hardcover 9781442417007(5.2 MB)

- Author Photo (jpg): Dia Calhoun Photograph by Maureen Hoffmann(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit