Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

LIST PRICE $10.99

PRICE MAY VARY BY RETAILER

Get 30% off hardcovers with code MOM30, plus free shipping on orders of $40 or more. Terms apply.

Buy from Other Retailers

Table of Contents

About The Book

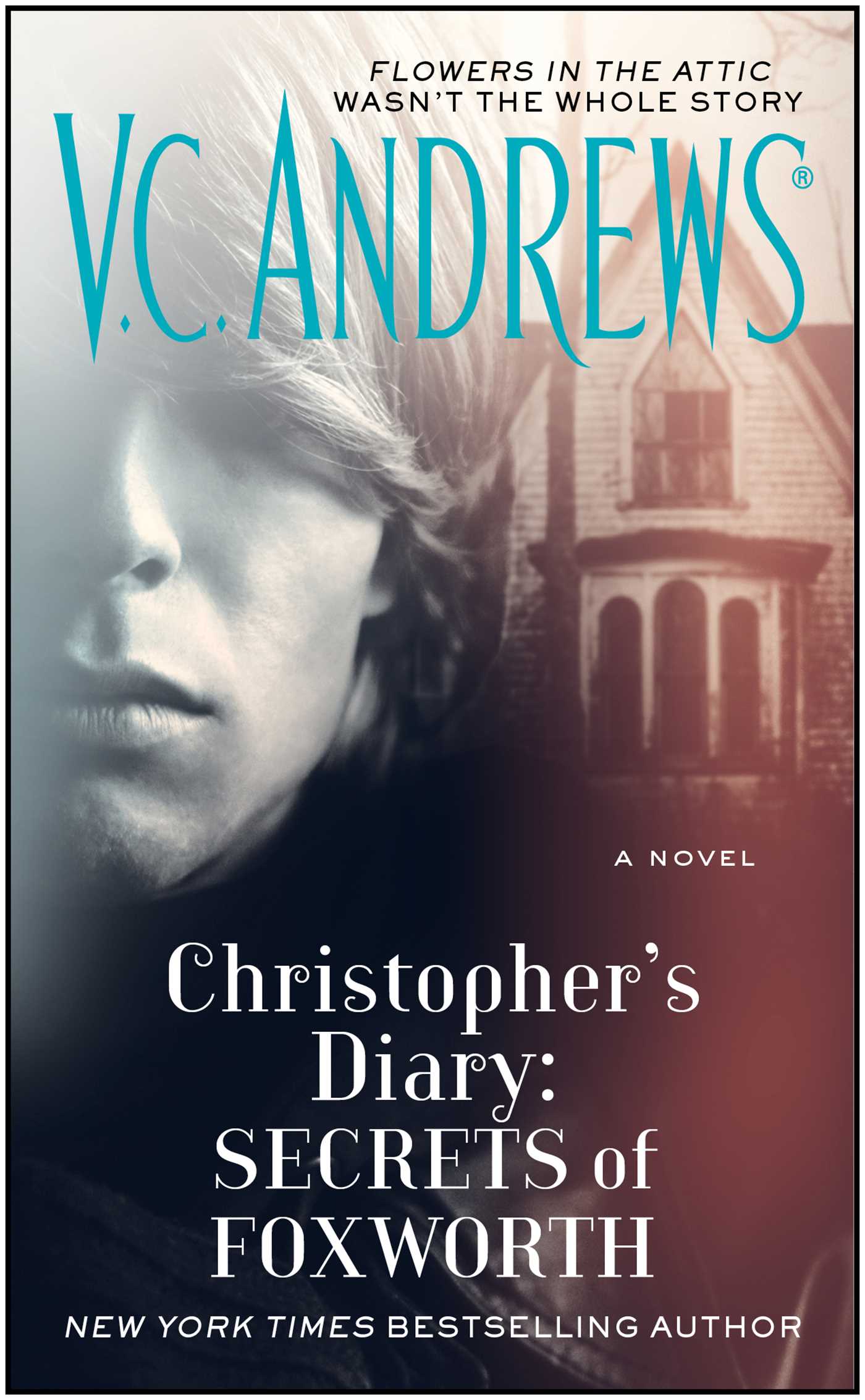

The discovery of Christopher’s diary in the ruins of Foxworth Hall brings new secrets of the Dollanganger family to light in this riveting novel from V.C. Andrews, the author of Flowers in the Attic and Petals on the Wind, both major Lifetime TV events.

Christopher Dollanganger was fourteen when he and his younger siblings—Cathy and the twins, Cory and Carrie—were locked away in the attic of Foxworth Hall, prisoners of their mother’s greedy inheritance scheme. For three long years he kept hope alive for the sake of the others. But the shocking truth about how their ordeal affected him was always kept hidden—until now.

Seventeen-year-old Kristin Masterwood is thrilled when her father’s construction company is hired to inspect the Foxworth property for a prospective buyer. The once grand Southern mansion still sparks legends and half-truths about the four innocent Dollanganger children, even all these decades later. Foxworth holds a special fascination for Kristin, who was too young when her mother died to learn much about her distant blood tie to the notorious family.

Accompanying her dad to the “forbidden territory,” they find a leather-bound book, its yellowed pages filled with the neat script of Christopher Dollanganger himself. Her father grows increasingly uneasy about her reading it, but as she devours the teen’s story page by page, his shattering account of temptation, heartache, courage, and betrayal overtakes Kristin’s every thought. And soon her obsession with the doomed boy crosses a dangerous line…

Christopher Dollanganger was fourteen when he and his younger siblings—Cathy and the twins, Cory and Carrie—were locked away in the attic of Foxworth Hall, prisoners of their mother’s greedy inheritance scheme. For three long years he kept hope alive for the sake of the others. But the shocking truth about how their ordeal affected him was always kept hidden—until now.

Seventeen-year-old Kristin Masterwood is thrilled when her father’s construction company is hired to inspect the Foxworth property for a prospective buyer. The once grand Southern mansion still sparks legends and half-truths about the four innocent Dollanganger children, even all these decades later. Foxworth holds a special fascination for Kristin, who was too young when her mother died to learn much about her distant blood tie to the notorious family.

Accompanying her dad to the “forbidden territory,” they find a leather-bound book, its yellowed pages filled with the neat script of Christopher Dollanganger himself. Her father grows increasingly uneasy about her reading it, but as she devours the teen’s story page by page, his shattering account of temptation, heartache, courage, and betrayal overtakes Kristin’s every thought. And soon her obsession with the doomed boy crosses a dangerous line…

Excerpt

Christopher’s Diary: Secrets of Foxworth Early Days

“Where are you going today, Dad?” I asked.

It was Saturday, and he hadn’t mentioned any new construction job. I had come out of the kitchen, where I had just finished the breakfast dishes, and I saw him in the entryway pulling on his reluctant knee-high rubber boots, the muscles in his neck and face looking like rubber bands ready to snap. He already had his khaki “aged like wine” leather coat and faded U.S. Navy cap on. His tool belt lay beside him on the oak wood bench he had built, its heavy leather belt curled on itself like some sleeping snake. It had been a birthday present from my mother nearly ten years ago, but with the tender loving care he gave it, it looked like it had been bought yesterday.

I wasn’t surprised to see him dressing like this. It was October, and we were having weird weather. Some days were cooler than usual, and then suddenly, some days were much warmer, and we also had more rainy ones in Charlottesville for this time of the year. Whenever anyone complained about the unusual changes in the weather, Dad loved to resurrect an old ’50s expression, “Blame it on the Russians,” rather than just saying “Climate change.” Most people had no idea what “Blame it on the Russians” meant, least of all any of my friends, and few had the patience to listen to any explanation he might have. Dad wasn’t old enough to personally remember, of course, but he told me his father had said it so often that it became second nature for him, too.

“Oh. Didn’t I say anything about it at breakfast?”

“You didn’t say much about anything this morning, Dad. You had your nose in the newspaper most of the time, sniffing the words instead of reading them,” I reminded him. He said that was something my mother would complain about, too. She used the exact same expression. She told him that eating breakfast with him was like sleepwalking through a meal.

My reliance on any of my mother’s expressions, whether vaguely remembered or coming from my dad’s descriptions, always brought a broad smile to his face. As if he had tiny dimmer switches behind them, his hazel eyes would brighten. Perhaps because of his constant time in the sun or his worry and sorrow, the lines in his forehead deepened and darkened more each year. His closely trimmed reddish-brown full-face beard had been showing a little premature gray in it lately, too. Dad was only forty-six, and ironically, there was no gray in his full head of thick hair, which he kept long but neatly trimmed. He wore it the same way he had when my mother was alive. He said she was jealous of how naturally rich and thick it was and forbade him to return to the military-style cut he had when they first met.

“Got to go inspect this mansion that burned down a second time in 2003. Herm Cromwell called me at the office just before I left yesterday, and I promised to do it today and get back to him even though it’s the weekend. Bank’s open half a day today. He’s been working hard on taking the property off the bank’s liabilities since that nutcase abandoned it and went off to preach the gospel. Herm wants me to estimate the removal and see if the basement is still intact. The bank has a live one.”

“A live one?”

“A client considering buying and building on the property, which, after two fires and all that bizarre history, hasn’t been easy to sell. Why? What are you doing today? What did I forget? Was I supposed to do something with you, go somewhere with you?” He pulled his lips back like someone who was anticipating a gust of bad news or criticism.

“No. I’m not doing anything special. I was going to pick up Lana and hang out at the mall.”

Lately, Lana and I had become inseparable. I was close with many of my girlfriends, but Lana’s parents were divorced, and sometimes her problems seemed close to mine, even if divorce wasn’t what made my father a single parent.

He relaxed, smiled, and shook his head gently. “?‘Hang out?’ You make me think of Mrs. Wheeler’s laundry. She still doesn’t have a dryer in her house. Don’tcha know they call you kids ‘mall rats’ these days? I hear they’re coming up with a spray or something.”

I laughed but nodded. Ever since I got my driver’s license last year, I looked for places to go, if for nothing else but the drive. As I watched Dad continue getting ready to leave, I thought about what he had said for a moment. And then it hit me: inspect the foundation of a mansion that had burned down a second time?

“This property you’re going to, it’s not Foxworth Hall, is it?”

He paused as if he wasn’t sure he should tell me and then nodded. “Sure is,” he said.

Foxworth, I thought. I had seen the property only once, and not really close up, but all of us knew the legends that began with the first building, before the first fire. More important, my mother had been third cousin to Malcolm Foxworth, which made me a distant cousin of the children who supposedly had been locked in the attic of the mansion for years. So much of that story was changed and exaggerated over time that no one really knew the whole truth. At least, that was what my father told me.

The man who had inherited it, Bart Foxworth, was weird, and no one had much to do with him. If anything, the way he had lived in the restored mansion only reinforced all the strange stories about the Foxworth family. He had little to do with anyone in the community and always had someone between him and anyone he employed. They called him another Phantom of the Opera. He had family living with him, but they had different names, and people believed they were cousins, too. One of them, who lived there only a few years before dying in a car accident, was a doctor who worked in a lab at the University of Charlottesville. Except for him, the feeling was that insanity ran in the family like tap water. At least, that was the way my father put it when he was pushed to say anything, which he hated to do.

“I’d like to come along,” I said.

Three years before my mother had died, Foxworth Hall had burned down for a second time. I was just five years and five months old at the time of her death. I really didn’t know very much about the place until I was twelve and one of my classmates, Kyra Skewer, discovered from gossip she had overheard when her mother was on the phone with friends that I was a distant cousin of the Foxworths. She began to tell others in my class, and before I knew it, they were looking at me a little oddly. Because everyone assumed the Foxworth family was crazy, many believed that their madness streamed through the blood of generations and possibly could have infected mine. The stories about the legendary Malcolm Foxworth and others in the family were the kind told around campfires at night when everyone was challenged to tell a scary tale. This one’s parents or that one’s uncle or someone’s older brother swore they had seen ghosts and even unexplainable lantern lights in the night.

Few tales were scarier to me or my classmates than this one story about four children locked in an attic for more than three years. All of them got very sick, and one of them, the youngest boy, died. Some believed that their mother and their grandmother wouldn’t take them to a doctor or a hospital. From that, others concluded that either both or just the grandmother maybe wanted them all dead. Part of the story was that the young boy might have been buried on the property. And on Halloween, there was always someone who proposed going to Foxworth, because the legend was that on that night, the little boy’s spirit roamed the grounds looking and calling for his brother and two sisters, even after the second fire. Some of my friends actually went there, but I never did, nor did Lana or Suzette, my other close friend. The stories those who did go brought back only enhanced the legend and kept the mystery alive. Some swore they had heard a little boy moaning and crying for his brother and sisters, and others claimed that they definitely had seen a small ghost.

Whatever was the truth, the stories and distortions made the property quite undesirable ever since. Since Bart Foxworth had abandoned the property, it had been quite neglected and eventually fell into foreclosure. So it was curious that someone was considering buying it. Whoever it was obviously was not afraid of the legends and curses. Bart Foxworth, in fact, was said to have believed that his reconstruction of the original building still contained evil, and that was why he left it and didn’t care to keep it up. It was said that he believed that God didn’t want that house standing. It was as though a dark cloud never left the property. People accepted the curse. Where else could you find a house with that kind of history that had burned to the ground twice? Who’d want to challenge the curse?

“Well if you want to come along, Kristin, get moving. Put on some boots and maybe a scarf. I have a lot to do there and want to get home for lunch and watch the basketball game this afternoon,” Dad said, and he clapped his black-leather-gloved hands together. “Chop, chop,” he added, which was his favorite expression to get someone moving.

My father had a construction company, simply called Masterwood, which was our last name. “With a name like mine,” Dad would say, “what could I eventually do but get involved in construction?” Masterwood employed upward of ten men, depending on the number of jobs contracted. My mother used to keep the books, but now Dad had Mrs. Osterhouse, a widow five years younger than he was whose husband had been one of Dad’s friends. I knew she wanted Dad to marry her, but I didn’t think he would ever bring another woman into our home permanently. He rarely dated and generally avoided all the meetings with women that anyone tried to arrange. For the last five years, I did most of our housework, and even when my mother was alive, Dad often prepared our meals, especially on weekends.

Right after serving in the navy, where he got into cooking, he had been a short-order cook in a diner-type restaurant off I-95. He met my mother before he began taking on side work at construction companies. She was a bookkeeper at one of them. Two years later, they married and moved here to Charlottesville, Virginia, where they both put their life savings into my father’s new company. They didn’t deliberately come here because she’d once had family here. My mother had never been invited to the Foxworth mansion, and hadn’t ever spoken to Malcolm or anyone else who had lived there. Dad said they not only moved in different circles from the Foxworth clan but also lived on different planets.

“Okay,” I said. “Wait for me.”

I ran upstairs to put on warmer clothing. I was actually very excited about going with him to Foxworth. I always thought Dad knew more than he ever had said about the original story, and maybe now, because we were going there, he would tell me more. Getting him to say anything new about it was like struggling to open one of those hard plastic packages that electronic things came wrapped in. When I came home from school armed with a new question about the family, usually because of something one of my classmates had said, he rarely gave any answers that were more than a grunt or monosyllable.

My cell phone buzzed just as I was turning to leave my room. It was Lana. In my excitement, I had forgotten about her.

“What time are you picking me up?” she asked. “We’ll have lunch at the mall.”

“Change of plan. I’m going with my father to Foxworth.”

“Foxworth? Why?”

“He has to estimate a job, and I promised I would help, take notes and stuff,” I added, justifying my going there. “Someone wants to build on the property.”

“Ugh. Who’d want to do that? It’s cursed. There are probably bodies buried there.”

“Someone who doesn’t care about gossip and knows the value of the property,” I said dryly. “It’s what businessmen do, look for a bargain and build it into a big profit.”

My father said I had inherited my condescending, often sarcastic sense of humor from my mother, who he claimed could cut up snobs in seconds and scatter their remains at her feet “like bird feed.”

“Oh. Well, what about Kane and Stanley? We were supposed to hang out with them, me with Stanley and you with Kane. I know for a fact that he’s expecting you.”

“I never said for sure, and he was quite offhanded about it.”

“Well, you never said no, and I know you liked him before when we were out. Emily Grace told me her brother told her Kane said he thinks you’ve grown into a pretty girl.”

“I’m so grateful for his approval.”

She laughed. “You like him, too. Don’t play innocent.”

“That’s all right. You never want any boy to take you for granted,” I said. “It’s good to disappoint him now and then.” She was right, though. I really wanted to be with Kane, but I wanted to go to Foxworth more. I couldn’t explain why. It had just come over me, and when I had feelings this strong, I usually paid attention to them.

“What? Who told you that? Are you reading some advice to the lovelorn or something? You’re not listening to Tina Kennedy, are you? She’s just jealous, jealous of everyone.”

“No. Of course not. I’d never listen to Tina Kennedy about anything. Gotta go,” I said. “Dad’s waiting for me. I’ll call you later.”

“Don’t touch anything there,” she warned. “You’ll get infected with the madness.”

“You forgot I had the shot.”

“What shot?”

“The vaccine that prevents insanity. It’s how I can hang out with you,” I added, and hung up before she could say another word. Besides, I knew she wanted to be on the phone instantly to spread the news. I was returning to some ancient ancestral burial ground, and surely the experience would change me in some dramatic way. They all might even become a little more afraid of me, but probably not Kane. If anything, I was sure he would find it amusing. He could be a terrific tease, which was one of the reasons I was a little afraid of him.

Laughing, I bounced down the stairs. I had my blond hair tied in a ponytail, and because of the length of my hair, the ends bounced just above my wing bones. Both my mother and I had cerulean-blue eyes, and part of the legend of the attic children was that they all had the same blue eyes and blond hair. The fact that I supposedly looked like them only enhanced the theory that I could have inherited the family madness.

I had never seen a picture of them, and Dad told me that he and my mother hadn’t, either. In fact, no one had seen any picture of them when they were shut up in the attic or even soon afterward. There were some drawings in newspaper stories, but their accuracy was always in question, as were the facts in the stories. Supposedly, the children who survived the ordeal never talked about what had happened, but that didn’t stop the tales of horror. They were always reprinted around Halloween with grotesque drawings depicting children scratching on locked windows, their faces resembling Edvard Munch’s famous painting The Scream, making it all look like someone’s nightmare. In a few weeks, those stories and pictures would appear again.

Years later, three of the children, as the story goes, returned to Charlottesville just before the second fire. Dad said neither he nor my mother had ever met any of them. Some people believed that the older sister had begun an affair with her mother’s attorney husband and that her mother was driven to madness and had actually been the one responsible for setting the first fire, which had killed Olivia Foxworth, Malcolm’s wife, who was an invalid at the time. The details remained vague, and none of the facts had been substantiated, even after the mansion was rebuilt and another Foxworth moved in many years later, which only made it all more interesting.

I could never understand it. If the story about the children locked in an attic was true, why would the children want to return to Charlottesville, let alone to Foxworth Hall? That would be like a prisoner wanting to return to his jail cell. Why revive such painful memories, unless those memories were really just the product of someone’s wild imagination? And why would her mother’s husband want to have an affair with a girl that young?

Maybe more important, why would she want to have an affair with him? No one knew where the older brother and sister were now. Some say they changed their names or left the country. The cousins who moved into the second mansion never told anyone anything, either, and even if Bart Foxworth had said something, it wouldn’t have been believed. It was like that campfire game where you whisper a secret into someone’s ear and they whisper it to the person next to them, who does the same, until the secret works its way back, and by then, the original secret is so distorted it barely resembles what the first person told.

It was like pulling teeth to get Dad to tell me anything. If I brought home another tidbit and persistently asked him about it, he would finally say, “I wouldn’t swear to any of it being true. As your mother used to say, exaggerations grow faster than mold in a wet basement around here. I told you, Kristin, forget about all that. Just thinking about it could poison your mind.”

Just thinking about it could poison my mind? No wonder the Foxworth property was an ideal Halloween hangout, populated with ghosts and moans and screams. But how could I help wanting to know more? I didn’t tell Dad about it because I knew it would upset him, but on many occasions when new kids were introduced at school or at parties, someone would say something like, “You know, Kristin is related to the famous Foxworth children on her mother’s side.”

Inevitably, the new kid would ask, “Who are the famous Foxworth children? Why are they famous?”

Then someone would go into one of the versions of the story, with everyone looking to me to tell them more. They were very skeptical when I said, “I don’t know any more than you do about it, and half of what you’re saying is surely the product of distorted imaginations.” I’d walk away before anything else could be said to me, not as if I wanted to hide anything but acting more like I was bored with the subject. Of course, I wasn’t.

Why should I be? Everyone is interested in his or her family background. It’s only natural. I’d been in many of my girlfriends’ homes for dinner when their parents brought up memories of their grandfathers and their uncles and aunts and cousins. Pictures of relatives were hanging on walls. I couldn’t imagine my mother ever putting up a picture of Malcolm Foxworth or Olivia Foxworth, not that she’d had any. She had some very old photographs of relatives, but to this day, I didn’t know who was who, and if I asked Dad about any of them, he would claim he couldn’t remember. Maybe he was telling the truth, or maybe he was just avoiding it.

Everyone’s family had black sheep, but also relatives they were proud to mention. My family background on my mother’s side had this big, gaping black hole full of terror and horror. Was it a good idea to try to fill it, or was it better just to cover it up and forget? Forgetting about it was just not very easy, at least not for me.

It was like everyone knew that your cousin many times removed was Jack the Ripper. Despite the distance in relationship, they were always looking for some sign, some indication that you carried the germ of evil. Instead of Typhoid Mary, I was Madness Kristin. Get too close to me, and you might become a blabbering idiot.

Dad was already outside checking something on his truck engine. The truck was practically a member of our family. I couldn’t remember him not driving it. When I asked him why he didn’t buy a new one instead of constantly tinkering with it, replacing parts, and filling in rust spots, he replied in one word, “Loyalty.” When I looked confused, he continued, reciting one of his favorite lectures. “Problem with the world today is everything in people’s lives is temporary. It spreads from their possessions to their relationships. They throw away their marriages as easily as they dump their appliances. This truck’s never let me down. Yes, it’s old, and it ain’t pretty, but it’s used to me, and I’m used to it.”

Fortunately, once I got my driver’s license, he had decided that I should have a modern car with all the safety bells and whistles. However, when he had to trade in my mother’s car to get mine, he was almost as upset as he was the day she died. To this day, he refused to give away her clothes and shoes. They were all stored in our attic with some of her other things like hairbrushes, curlers, and perfume. It was almost as if he hoped she would turn up at the door, smile, and say, “My death was a terrible mistake. I wasn’t supposed to be taken yet, so I’m back.” That was why he loved watching the movie Heaven Can Wait.

More than once, I caught him staring at an empty doorway or listening keenly for the sound of her footsteps on the stairway.

People never really die until you forget them, I thought.

I couldn’t ever blame him for believing she might return somehow. From what I remember and from what people tell me, no one expected my mother to die like that. She was a very healthy-looking thirty-four-year-old woman. They called it a cranial aneurysm. Something just exploded in her head, and she keeled over one day at work. She didn’t die right away. Dad had a very difficult time talking about it for years, but when he did talk to me about it, I could see he was always amazed at how well she had looked in the hospital bed.

“It’s why I couldn’t believe the doctors,” he told me. “I sat there thinking any moment she would wake up and bawl me out for putting her into the hospital to start with. That was your mother,” he would add. He would add that to almost anything he told me about her, “That was your mother,” signifying in his mind and mine that she was a very special person.

I had good memories of her, but a girl of almost five and a half certainly hadn’t experienced her mother long enough to know her as well as she should. Without her now, I could hear nothing much about her side of the family. She was an only child. My maternal grandfather died very young from heart failure, and my maternal grandmother, who also had health problems, died when I was only seven, so I didn’t get to know them that well, either.

The only uncle and aunt I had were on my father’s side. My father’s younger brother, my uncle Tommy, lived in California, where he worked as an agent in a talent agency. He never married or had children. Dad had a younger sister, Barbara, who was also unmarried and worked at a bank in New York. Dad’s father had been killed in a car accident. He was only in his early fifties at the time. My paternal grandmother had lived with Dad’s younger sister, Barbara. She eventually succumbed to emphysema and then pneumonia. She had been a heavy smoker, as was Dad’s father. Dad wouldn’t permit anyone who worked for him to smoke in his office or on any of his jobs. He actually made them sign an agreement and did fire a young man who smoked on a site.

I spoke to my aunt Barbara occasionally and visited with her in New York City last summer, which was one of my best trips without Dad. She was constantly inviting me to return so she could take me to shows and wonderful restaurants. Of course, she invited Dad, too, but he hated big cities.

“I’m just a small-town boy,” he would say. “You can take the boy out of the country, but you can’t take the country out of the boy.” I kidded him often about being stuck in his ways. He never denied it. “I am who I am,” he would say. “One size Burt Masterwood fits all. Besides, you’ll do all the traveling and discoveries in this family, Kristin. I did enough when I was in the navy.”

Would I travel and make discoveries? I would go to college, but I still had no definite idea what I wanted to become. For a while, I thought about being a teacher. Lately, I considered going into medicine, maybe research. Perhaps it was because I had lost my mother when I was so young, or maybe it was because of the Foxworth legend that hovered over me, but sometimes I felt I was lost in a fog, the most difficult thing to know being my future. I dreamed of marrying someday and having my own children, but that also seemed more like a vague dream, something coming sometime, somehow, like a handsome prince riding in from some mysterious place.

“?’Bout time,” Dad said when I popped out of the house and closed the door. “Let’s go.”

He closed the truck hood with the same gentleness he employed whenever he did anything on his truck. He did treat it like some revered old friend, full of mechanical arthritis but still ambulatory. Sometimes I would catch him just looking at it and stroking it affectionately, lost in some memory or maybe just thinking about my mother sitting beside him.

“What’s wrong with Black Beauty today?” I asked as I opened the door to get in. The black leather seats were creased and faded, but there wasn’t a tear in either of them, and the carpeting on the floor was always kept up or replaced.

“Got to change her spark plugs. She reminds me every morning. Just like a woman, nag, nag, nag,” he said, and started the engine. He listened to it and nodded. “Spark plugs,” he repeated, and then backed out of our driveway.

We had a modest two-story Queen Anne–style home with recently renovated aluminum siding, black shutters, and panel windows in the bay Dad had built in the living room. All the bedrooms were upstairs, the wall paneling redone. Recently, Dad replaced the balustrade on the stairway with a rich dark mahogany, saying that it was something my mother would have liked. He was still doing things he knew would have pleased her. I was so used to him being able to fix and refurbish everything in our home that I grew up thinking every man could do that. I would smile incredulously when my girlfriends’ fathers had to call a repairman to repair a window casing or a plumber to fix a toilet. Besides being a licensed general contractor, Dad was a licensed plumber and electrician.

“I’m a hands-on man,” he would tell me proudly. “Your mother wasn’t above bragging to her friends about me, making me out to be Mr. Fix-It. But that’s how she was.”

Our house was on a side road next to a working horse and cattle farm. We were nearly twelve miles outside the city of Charlottesville in the eastern foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains. All of my friends were within what Dad called “striking distance,” so I never felt any more isolated than anyone else, although I did especially enjoy spending time with Missy Meyer, whose father, Justin Anthony Meyer, was an important attorney and who lived in a classic 1900s brick Victorian home in the Belmont neighborhood of Charlottesville. It was only a block away from the Pedestrian Mall. Dad had done some renovation work for Mr. Meyer, laying down new pine floors and later redoing a bathroom.

“How many people died in the first Foxworth fire, Dad?” I asked once we were on our way, hoping to get him to start talking more about it.

“Far as I know, only two, the old lady and her son-in-law.”

“That attorney who had an affair with one of the granddaughters?”

He looked at me. I could see he was making a decision. Until now, it was clear that he didn’t want to contribute any more to the dark details that surrounded my mother’s cousins and the events that had occurred in that grand old mansion. He had scared me when he’d said that just thinking about them could poison my mind, but now that I was older, maybe it wasn’t as dangerous.

“That’s what I was told,” he said, “but I don’t consider anyone I know to be anything of an authority on it. The Foxworths were very private people, and when people are that private, the only way you get to know anything about them is second- or thirdhand. Worthless.”

“Did you really believe that the children’s grandmother wanted her own grandchildren dead and was somehow responsible for the little boy dying?”

“No one as far as I know proved anything like that,” he said. “It’s a nasty story, Kristin. Why harp on it?”

“I know, but probably not much nastier than what they’re showing at the movie theater.”

He nodded. “I’ll give you that.”

“There are lots of stories like it on the news today also, Dad.”

“Look, I’m like most people around here, Kristin. What I know about the Foxworth tragedies I know from little more than gossip, and gossip is just an empty head looking to exercise a fat tongue.”

“Do you think the little boy’s body is buried somewhere on the property? You must have some thought about that.”

“Not going to venture a guess on that, and I’m not going to be one to spread that story, Kristin. You know how hard it is to sell a house in which someone died? People get spooked. Look how long it’s taken to move this property, and there’s no reason for that, even though the house on it burned down twice. It’s prime land.”

“How did it burn the second time? I heard an electric wire problem.”

“That’s it,” he said. “It was abandoned, so no one noticed until it was too late.”

“I also heard the man who lived in it burned it because he believed it had the devil inside it.”

Dad smirked. “There was no proof of arson. All that just adds to the rumor mill.”

“The same house burns down twice?” I said.

He looked at me and then looked ahead and said, “Lightning can strike twice in the same place. No big mystery.”

He made a turn and started us on the now-infamous road to Foxworth, passing cow farms along the way. There had been a number of times when I was tempted to use my new driver’s license and take myself and one or two of my friends out to Foxworth, but somehow the aura of dark terror hovered ahead of me when I considered it, even in broad daylight. And I didn’t want any of my friends to know I had an interest in the Foxworth legends. That would only encourage their insinuations that I might have inherited madness.

“Did Mom ever talk about what happened, Dad?”

“You mean the first fire?”

“No, all of it, especially the children in the attic.”

“Her girlfriends were always trying to bring it up, I know, but she would say something like, ‘It’s not right to talk about the dead,’ as if it was some Grimms’ fairy tale or something, and that would usually end it. But that didn’t mean they didn’t keep trying. A busybody has got to keep busy.”

“Did she talk about it with you?”

He gave me that look again, the expression that told me he was considering my age and what he should say. “I told you, Kristin, it’s all hearsay, even what your mother knew and what we were told years later.”

“I’m all ears,” I replied.

He shook his head. “I’m going to regret this conversation.”

“No, you won’t, Dad. I won’t be the one to tell stories out of school,” I added, which was another one of his favorite expressions. I knew he loved that I used them, remembered them.

“Your uncle Tommy once claimed he had met someone who said he had known one of the servants in the original house at the time the children were supposedly locked in the attic. He went out to Hollywood to pitch the story for a movie, and Tommy heard it. He called us immediately afterward.”

“What did he say?”

“He said the man claimed it was true that they were up there for more than three years, a girl who was about twelve when they were first locked up, a boy who was about fourteen, and the twin boy and girl about four. Their father was killed in a car accident and supposedly didn’t leave them enough money to fix the heels on their shoes. Malcolm Foxworth was pretty sick by then, but he hung on for a few years more. The story was that he wouldn’t put his daughter back in his will if she had children with her husband.”

“Do you know why? Did he say?”

“He was vague about it. Tommy, who hears lots of stories, said he was sure the man was making most of it up as he went along just to season his story enough to sell it for a movie.”

“Did it fit with anything you had heard or knew already?”

“I told you, I never really knew what was true and what wasn’t. What I do know from what the old-timers tell me is that Malcolm Foxworth was a real Bible thumper, one of those who believed Satan was everywhere, and so he was very strict. Whatever his daughter did to anger him, forgiveness was a part of his Christianity that he neglected. That’s what your mother would say. She didn’t even like being known as a distant relative, and to tell you the truth, she would cringe whenever anyone brought that up. She’d be angry at me for telling you this much hearsay.”

“So?” I asked, ignoring him. “At least tell me what else Uncle Tommy told you.” Despite his reluctance, I thought I had him on a roll. He had already said ten times as much as he had ever said before about the Foxworth family story.

“According to the story the man pitched, the kids were hidden up there so Malcolm wouldn’t know they existed.”

“So that part is really true?”

“I told you. The guy was trying to sell a story for a movie.”

“But even in his story, why did that matter, not knowing they existed?”

“I guess Malcolm thought they were the devil’s children. Anyway, your uncle says that this servant who was the main source for the story swears the old man knew and enjoyed that they were suffering.”

“Their own grandfather? Ugh,” I said.

“Yeah, right, ugh. So let’s not talk about it anymore. It’s full of distortions, lies, and plenty of ugh.”

I was quiet. How did the truth get so twisted? Why was no one sure about any of it? “What a mess,” I finally muttered.

“Yeah, what a mess. So forget it.” He smiled. “You’re getting to look more like your mother every day, Kristin. You lucked out. I have a mug for a face.”

“You do not, Dad. Besides, if you did, would Mom have married you?”

He smiled. “Someday I’ll tell you how I got that woman to say ‘I do.’?”

“I already know. She married you because she knew you could fix a leaky faucet. And that’s just the way she was.”

He laughed. If he could, he would have leaned over and kissed me, but he didn’t want to show me any poor driving habits, especially now that I was driving.

We rode on. It was right ahead of us now, and I could feel my breath quicken.

It was like opening a door locked for centuries.

Behind it lay the answers to all the secrets.

Or possibly . . . new curses.

Somehow I sensed that I was finally on the edge of finding out.

* * *

I was disappointed as we approached what was left of the second Foxworth Hall, which supposedly was a duplicate of the first. It looked more like a pile of rubble than the skeleton of a once proud and impressive mansion full of mystery and secrets. There were weeds growing in and around the charred boards and stones. Shards of broken glass polished by rain, snow, and wind glittered. Anything of any color was faded and dull. Rusted pipes hung precariously, and the remains of one large fireplace looked like they were crumbling constantly, even now right before our eyes.

Most of the grounds were unkempt and overrun, bushes growing wild, weeds sprouting through the crumbled driveway, and the fading grass long ready to cut as hay. Four large crows were perched on the stone walls, looking as if they had laid claim to the place. They burst into a flurry of wings and, looking and sounding angry, flew off as we drew closer. They, along with rodents and insects, surely had staked title to all of it years ago. Otherwise, it looked as quiet and frozen in time as any rarely visited graveyard.

Another truck was already parked near the wrecked mansion. I recognized Todd Winston, one of the men who had been with Dad for years. Todd had married his high school sweetheart, Lisa Carson, after she had gotten her teaching certificate and begun to teach fifth grade. Three years later, they had their first child, a girl named Brandy, and two years later, they had Josh. Dad was only about ten years older than Todd, but Todd treated him more like a father than an older brother. He was always looking for Dad’s approval. He had a full strawberry-blond beard and a matching head of hair that looked like it was allergic to a brush most of the time.

“The property has a lake on it fed from underground mountain streams,” Dad told me. “It’s off to the left there, about a fifteen-, twenty-minute walk, if you want to see it,” he said. “We’re going to be here a good two hours or so. No complaints about it,” he warned. “You wanted to come along.”

“I won’t complain. I’ve canceled all my important appointments for the day, including tea with the governor.”

“Wise guy,” Dad muttered, clenching his teeth but smiling.

“I’ve already seen two raccoon families who won’t appreciate us bulldozing all this away, not to mention those crows,” Todd said as soon as we got out of the truck. “Hi, Kristin. Your dad putting you to work in construction already?”

“No. I’m just along for the ride.”

“The ride?”

I nodded at the wreckage. “I just want to see it all close up,” I told him, and he nodded and looked back at what was left of the mansion.

“Hard to believe it was once the place people describe, with a ballroom and all, magnificent chandeliers, elaborate woodwork, and stained-glass windows. People who live in houses like this usually don’t get burned out. The rich don’t die in fires.”

“Hogwash. Fire and water don’t discriminate,” Dad said. “Besides, that’s how the world will end if we don’t find a better way, and goodness knows, we’re working on it.”

“Thanks for the cheery news, Burt,” Todd said. “Where do you want to start?”

“We’ll begin on the east end here.” He stared at it all a moment and then nodded. “They don’t build foundations like this anymore. It’s the original one. Who’d build one like it now? It’s the instant gratification generation, including instant house slapped together with spit and polish.”

“Amen to that,” Todd said.

He’d say amen to anything Dad uttered, I thought. He didn’t have much of a mentor in his own father, who Dad said was as useless as a screw without a head. He spent most of his time nursing like a baby on a bottle of beer and was one of the fixtures at Hymie’s Bar and Grill just southeast of the city.

Dad looked at me with those expectant eyes. Now that I was here, he was anticipating my disappointment. There was nothing sensational to see, no clues to what had happened here either the first or the second time. There was no way to understand how elaborate the mansion had once been. I saw legs of tables and chairs and crumbled elaborate stonework, but remnants of beautiful pictures, statues, curtains, and chandeliers were burned up or so charred that they were unrecognizable. There was certainly not much for me to do.

“I’ll be fine,” I said. “I’ll take that walk to the lake.”

“You be careful,” he said.

“Watch out for ghosts,” Todd called.

“Mind yourself,” Dad told him, and Todd laughed.

They started toward the foundation, and I walked around it all first. I kept looking up, trying to imagine the way the mansion stood, how high it really was, and where exactly the attic loft in which the children spent most of three years would be. Would they have had any view? Maybe they could have seen the lake. And if they had, would that have made things easier or harder, looking at places they couldn’t go to and enjoy? The surrounding forest was thick, the trees so tall that from my position, I could barely make out some of the hills in the distance, and only the very tops of them at that. But it had been decades since they had been here. The trees weren’t so high back then.

I saw Dad and Todd begin measuring parts of the remaining structure, moving charred wood, and inspecting the walls of the foundation carefully, as if they anticipated something grotesque jumping out at them. Right now, it was difficult to imagine anything frightening about Foxworth. It looked like one of the structures devastated in bombings during the Second World War that we saw in films in history class. However, I knew there were even adults who believed that if they stood inside the wreckage at night, they could hear screams and cries, even laughter and whispers.

Do all houses keep the sounds of those who have lived in them, absorb them into their walls like a sponge would absorb water, and then, in the quiet of the night after they are deserted or left waiting for the wrecking ball, free the memories to wander about the rooms, resurrecting happy times and sad ones?

I started to make my way to the forest and then walked slowly through the cool woods. Most of the leaves were gone because of the recent wind and rain, but some had clung determinedly to their branches and flooded the forest with their bright yellow, brown, and amber colors. Where there were thick pine trees, there were shadows. I saw rabbits and thought I saw a fox, but I wasn’t sure, as it moved so quickly out of sight. About fifteen minutes later, I reached the edge of the lake my father had described. The ducks had already gone south. There were few birds, in fact, not even the crows I had seen. The lake was still, desolate, and silvery with clouds reflected in the surface and small circles here and there created by water flies.

Almost halfway around the lake, I saw what looked like a collapsed dock, most of it underwater. I drew closer, looking for signs of fish or turtles in the water as I walked, and then suddenly, I stopped and shuddered. The rocks and grass beneath the surface of the pond in one spot had somehow taken the shape of a small child. I knew it wasn’t real, but it looked so much like a skull and skeleton that I gasped and backed away.

A dead little boy very well could be in the lake.

Why not?

A lake would be a perfect place to hide a dead child, weigh him down, and let him sink to the darkness below. When I closed my eyes, I imagined him staring up from the bottom with his glassy eyes. I was suddenly much colder than I had been. I thought I heard an owl, but that was unusual in the daytime. What was it? I hugged myself, turned, and started back, moving more quickly now, actually trotting and then slowing down.

When I stepped out of the forest, I could see that Dad and Todd had moved around three-quarters of the property, making their evaluation. Dad looked up, saw me, and beckoned.

“Did you find the lake?” he called as I approached.

“Yes, but it looks so cold and deserted with so much overgrown around it. I’m sure it was once very pretty.” I didn’t want to mention the strange sound I had heard. Todd might start teasing me again.

“Probably good duck hunting in the spring,” Todd said. “But the land’s been posted for years.”

“We found something,” Dad said when I reached them. “From the looks of it, we think it was part of the original house. When the second Foxworth Hall was built, they didn’t do much about the original basement.”

“No one can read what happened to a house like your father can,” Todd said. “You know he’s been called in to evaluate some properties that burned down where there might have been a murder or somethin’.”

“All right. Enough of that,” my father said.

I didn’t know about those things, but right now, I wasn’t as curious about other houses or stories as I was about this one. “What did you find?” Had they found the remains of the child? Probably not. He wouldn’t sound so casual about that.

“Todd moved some boards that had to have been in the original basement and shifted a few things, and that appeared.” Dad nodded at a dark brown metal box about seven or eight inches long and six inches wide. “It’s locked,” he continued. “Might mean something valuable is inside it.”

I knelt beside it. There was a lot of rust.

“Look at what was scratched on the side,” Todd said, and I turned it to look.

“It’s a date: ‘11/60.’ That’s November 1960. More than fifty years ago,” I said.

Todd nodded as if we had found something that belonged in a museum alongside Egyptian ruins. “Maybe there are millions of dollars in jewels inside it,” he said. “Old jewels are worth more, aren’t they?” he asked my father.

“Maybe a hundred-year-old cameo or something,” my father offered.

I looked up at him. Was he serious? “Really?”

“Or thousands in cash. People used to keep money under the mattress, especially someone like old man Foxworth, who I heard was a real tightwad unless it was for the church,” Todd said, wishing that we would find money.

Dad smiled at him. “Well, he’s not wrong. People still hide money in their homes. They’re afraid the banks will find a way to steal it. Anyway, Kristin, we waited for you to open it. Ready?”

“Sure.”

He pulled a hammer out of his tool belt and knelt beside me. Then he put the back of the hammer under the latch and began to force it up. It gave way quickly because it was so rusted through. He handed the box to me. “Yours to open,” he said.

Slowly, I lifted the top and gazed down into the box. There were no jewels, and there was no money. There was only what looked like a leather-bound diary. I plucked it out carefully and showed it to my father and Todd.

“Maybe it has a treasure map in it or something,” Todd said, disappointed.

I opened the cover carefully, as the pages looked yellowed and fragile. “No, it’s actually someone’s diary,” I said.

“Unless it’s Thomas Jefferson’s, there’s no money in it,” Todd declared mournfully.

Dad smiled and shrugged. “He’s probably right. We’re about finished here. The foundation is in pretty good shape. Whoever the buyer is could build on it if he wants. I’ll just make a few notes, and we’ll head out.”

I put the diary back into the box and went to our truck. After I got in, I put the box on the seat and then sat back and took out the diary again.

The very first page identified whose it was. It read: Christopher’s Diary.

I thought for a moment. Christopher? Who was Christopher? Was he one of Malcolm Foxworth’s servants or relatives?

I read the first page.

When I was twelve years old, I read “The Diary of Anne Frank.” First, I was interested in it because it was written as a diary, and when someone writes a diary, he or she usually doesn’t expect anyone else will read it. A diary is like a best friend, someone to whom you could confide your deepest, secret thoughts safely. I really didn’t have a best friend. This would be it. I thought that whatever was in a diary had to be the most honest words anyone could write about himself or herself and about the people he or she loved and the people he or she met.

How do you lie in a diary?

I looked up when Dad opened his door to get in. He unwrapped his tool belt and put it behind the seat.

“So, whatcha got?” he asked as he got behind the wheel.

“A diary written by someone named Christopher.”

“Really?” He started the engine.

“Do you know who it might be?”

He started to turn the truck to drive off. Todd beeped his horn and waved to us, and Dad waved back.

“Christopher, huh? Well, it could be one of those kids in the attic. I seem to remember now that the older boy was named Christopher.” He glanced at me. “It might be nothing but someone’s silly ramblings, Kristin. More garbage about the Foxworth family. I wouldn’t waste my time reading it.”

He looked at the diary. I put it away.

“What a place this was,” he continued as we pulled away from the property. “Land with a lake on it like that. I’d buy it myself if I had the money. Too bad there wasn’t any in that box, or at least valuable jewelry. We’d make an offer.”

I looked down at the diary again. Maybe it was worth more than Dad thought. There was no way to know without reading it, but I didn’t want to read it while we were driving. I never liked to read in a car or in the truck while it was moving. It made me dizzy. The writing was all in script, but it was a careful, neat script that, although it was slightly faded in places, was quite legible.

We had to stop at the quick market for some basic groceries on the way home, so for a while, I put the diary out of my mind and concentrated on what we needed. When we got home, I helped carry the bags of groceries in first. After everything was put away, I went back to the truck and got the metal box.

Dad was on the phone making a report to the president of the bank about the property. I went past him and up the stairs to my room. I took off my sweater and got comfortable before I fixed my pillows and sat on my bed with the box beside me. Then I opened it, took out the diary, and again, very carefully, began to turn the page after the line How do you lie in a diary?

Years later, I would remember “The Diary of Anne Frank” for another reason, a more dramatic reason. Just as Anne Frank was forced to hide in an attic, my sister Cathy, our twin brother and sister, Cory and Carrie, and I were forced to hide in our grandparents’ attic. We weren’t hiding from Nazis, of course, but the way our mother described her father and the way our grandmother Olivia treated us, we probably didn’t feel much less afraid than poor Anne Frank.

Anne Frank’s father had her diary published. He wanted the world to know her story, their story. Everyone sees the same story in a different way. My sister saw our story one way, and I saw it another. When I began writing this, I didn’t do it because I thought it was so important to tell it from my eyes and ears and memories. But now I do. So I’ll be more careful about what I continue to write.

I paused to catch my breath. Is this what I thought it was? Dad’s guess about who Christopher could be was right, but more important, this was not some silly rambling, as he had said. It was so well written. I was excited, and I wondered if I should call Lana or Suzette. All my friends would like to know about this. I reached for the phone and then stopped.

No. I thought there was something about a diary that demanded respect. Although Christopher wrote that he had come to the point where he wanted his view of everything to be known, I felt very special being the first one ever to read it. I should read it all first and not tell anyone about it until I was finished, I decided. It was almost a sacred trust. Maybe I was meant to be the one to discover it because I was a distant relative.

Others might not see it that way. They might just see it as something sensational and tell me to send it to a supermarket rag or something. I could just hear Missy Meyer saying, “You could get lots of money for it, maybe. I’ll ask my father to look into it for you. The local newspaper might pay you and serialize it. You’ll be famous and make a lot of money!”

No, thanks, I thought. This was too special. I returned to the diary, now determined to read as much as I could before I went to sleep.

There are times now when I think back to what our lives were like in the mid-’50s and remember it all the way you might remember a dream. Often, with dreams that are so vivid, you’re not sure how much of it was fantasy and how much of it was real. There is so much of it that I want to be true, but I’m not the kind of person who is comfortable fooling himself.

I’ve always had a lot to think about, so it’s not really so unusual for me to have decided to keep a diary. My thoughts are very important to me. This diary will be a way of keeping my history, our history, authentically. Nothing Momma has said, nothing Cathy has said, and nothing Daddy has said will be as easy to recall later on when I’m much older if I don’t remember to write down what was important as soon as I can.

I didn’t do this right away. I kept telling myself diaries were something girls kept, not boys. Then I read about some famous diaries in literature and, of course, ships’ captains’ logs, all written by men, and I thought, this is silly. There’s nothing absolutely feminine about writing your thoughts down, about capturing your feelings. I just wouldn’t do something silly like write “Dear Diary.” I’d just write everything as it happened and be as accurate as I could.

I bought this diary myself with my allowance, but I never told anyone I had, not even my father, who was interested in everything I did and thought. It seemed to me that the whole point of keeping a diary was keeping that secret until it was time to let others read it, if that was your purpose. And it would be no good if it was done cryptically so that people had to figure out what I meant here and what I meant there. That’s why I have to be as honest as I can about what I saw, what I heard, and especially what I felt.

Like Otto Frank, I think it’s important that more people know what really happened to us before and afterward. Cathy used to call us flowers in the attic, withering away. It helped her to think of us that way. But we weren’t flowers. We were young, beautiful children who trusted that those who loved us would always protect us even better than we could protect ourselves.

Besides, I can’t ever think of us in any symbolic way. We weren’t the creations of someone’s imagination. We were real flesh-and-blood children. We were locked away, not only by selfish greed but by cruel hearts that used the Bible like a club to pound out the love we carried in our innocent hearts. How that happened and what became of us is too important to just let it disappear in the dying memories of those who lived it.

“Hey, you,” Dad said from my doorway. I was so involved in my reading I didn’t hear him come upstairs. He said he had been calling up to me.

“Oh, sorry, Dad. I didn’t hear you.”

“Aren’t you having any lunch today?”

“Oh, is it lunchtime?”

“You have a nice watch, Kristin, and four clocks in this room.”

“I don’t have four. Just the teddy bear clock and the Beatles alarm clock you found in an old house.”

“Okay. I’m going to make myself a ham and cheese sandwich. You want one?”

“Thanks, Dad.”

“You didn’t tell me if you wanted the chicken with pasta or the meat loaf tonight.”

“I’m a fan of your meat loaf, Dad. You know that.”

“Uh-huh. So what’s got you so involved? What is that, anyway?”

“You were right. It is the diary of the older brother, just as you thought it might be. He’s telling their story from his point of view.”

“Really? The whole story?”

“I think so. I just got into it.”

He stood there thinking. He narrowed his eyes and bit softly down on the left corner of his mouth as he always did when something troubled him. “I don’t know if you should read that, Kristin.”

“I won’t be corrupted by it if I haven’t already been corrupted by other things I’ve read.”

“Hmm,” he murmured. “There’s always a first time.”

“Oh, Dad. Besides, finally, I’ll know what really happened. We’ll know,” I said.

“I wasn’t dying to find out,” he replied. “And that still might not be the truth. Lies can be written as well as spoken, you know.” He started to turn away.

“I’ll be down in a few minutes,” I said.

“Does this mean you’re not going to mall-rat it today?”

“Yes, Dad, that’s what it means,” I said, laughing.

He was smiling himself as he walked away.

I returned to the diary like someone starving for news from the outside world, just like someone locked in an attic for years might be.

“Where are you going today, Dad?” I asked.

It was Saturday, and he hadn’t mentioned any new construction job. I had come out of the kitchen, where I had just finished the breakfast dishes, and I saw him in the entryway pulling on his reluctant knee-high rubber boots, the muscles in his neck and face looking like rubber bands ready to snap. He already had his khaki “aged like wine” leather coat and faded U.S. Navy cap on. His tool belt lay beside him on the oak wood bench he had built, its heavy leather belt curled on itself like some sleeping snake. It had been a birthday present from my mother nearly ten years ago, but with the tender loving care he gave it, it looked like it had been bought yesterday.

I wasn’t surprised to see him dressing like this. It was October, and we were having weird weather. Some days were cooler than usual, and then suddenly, some days were much warmer, and we also had more rainy ones in Charlottesville for this time of the year. Whenever anyone complained about the unusual changes in the weather, Dad loved to resurrect an old ’50s expression, “Blame it on the Russians,” rather than just saying “Climate change.” Most people had no idea what “Blame it on the Russians” meant, least of all any of my friends, and few had the patience to listen to any explanation he might have. Dad wasn’t old enough to personally remember, of course, but he told me his father had said it so often that it became second nature for him, too.

“Oh. Didn’t I say anything about it at breakfast?”

“You didn’t say much about anything this morning, Dad. You had your nose in the newspaper most of the time, sniffing the words instead of reading them,” I reminded him. He said that was something my mother would complain about, too. She used the exact same expression. She told him that eating breakfast with him was like sleepwalking through a meal.

My reliance on any of my mother’s expressions, whether vaguely remembered or coming from my dad’s descriptions, always brought a broad smile to his face. As if he had tiny dimmer switches behind them, his hazel eyes would brighten. Perhaps because of his constant time in the sun or his worry and sorrow, the lines in his forehead deepened and darkened more each year. His closely trimmed reddish-brown full-face beard had been showing a little premature gray in it lately, too. Dad was only forty-six, and ironically, there was no gray in his full head of thick hair, which he kept long but neatly trimmed. He wore it the same way he had when my mother was alive. He said she was jealous of how naturally rich and thick it was and forbade him to return to the military-style cut he had when they first met.

“Got to go inspect this mansion that burned down a second time in 2003. Herm Cromwell called me at the office just before I left yesterday, and I promised to do it today and get back to him even though it’s the weekend. Bank’s open half a day today. He’s been working hard on taking the property off the bank’s liabilities since that nutcase abandoned it and went off to preach the gospel. Herm wants me to estimate the removal and see if the basement is still intact. The bank has a live one.”

“A live one?”

“A client considering buying and building on the property, which, after two fires and all that bizarre history, hasn’t been easy to sell. Why? What are you doing today? What did I forget? Was I supposed to do something with you, go somewhere with you?” He pulled his lips back like someone who was anticipating a gust of bad news or criticism.

“No. I’m not doing anything special. I was going to pick up Lana and hang out at the mall.”

Lately, Lana and I had become inseparable. I was close with many of my girlfriends, but Lana’s parents were divorced, and sometimes her problems seemed close to mine, even if divorce wasn’t what made my father a single parent.

He relaxed, smiled, and shook his head gently. “?‘Hang out?’ You make me think of Mrs. Wheeler’s laundry. She still doesn’t have a dryer in her house. Don’tcha know they call you kids ‘mall rats’ these days? I hear they’re coming up with a spray or something.”

I laughed but nodded. Ever since I got my driver’s license last year, I looked for places to go, if for nothing else but the drive. As I watched Dad continue getting ready to leave, I thought about what he had said for a moment. And then it hit me: inspect the foundation of a mansion that had burned down a second time?

“This property you’re going to, it’s not Foxworth Hall, is it?”

He paused as if he wasn’t sure he should tell me and then nodded. “Sure is,” he said.

Foxworth, I thought. I had seen the property only once, and not really close up, but all of us knew the legends that began with the first building, before the first fire. More important, my mother had been third cousin to Malcolm Foxworth, which made me a distant cousin of the children who supposedly had been locked in the attic of the mansion for years. So much of that story was changed and exaggerated over time that no one really knew the whole truth. At least, that was what my father told me.

The man who had inherited it, Bart Foxworth, was weird, and no one had much to do with him. If anything, the way he had lived in the restored mansion only reinforced all the strange stories about the Foxworth family. He had little to do with anyone in the community and always had someone between him and anyone he employed. They called him another Phantom of the Opera. He had family living with him, but they had different names, and people believed they were cousins, too. One of them, who lived there only a few years before dying in a car accident, was a doctor who worked in a lab at the University of Charlottesville. Except for him, the feeling was that insanity ran in the family like tap water. At least, that was the way my father put it when he was pushed to say anything, which he hated to do.

“I’d like to come along,” I said.

Three years before my mother had died, Foxworth Hall had burned down for a second time. I was just five years and five months old at the time of her death. I really didn’t know very much about the place until I was twelve and one of my classmates, Kyra Skewer, discovered from gossip she had overheard when her mother was on the phone with friends that I was a distant cousin of the Foxworths. She began to tell others in my class, and before I knew it, they were looking at me a little oddly. Because everyone assumed the Foxworth family was crazy, many believed that their madness streamed through the blood of generations and possibly could have infected mine. The stories about the legendary Malcolm Foxworth and others in the family were the kind told around campfires at night when everyone was challenged to tell a scary tale. This one’s parents or that one’s uncle or someone’s older brother swore they had seen ghosts and even unexplainable lantern lights in the night.

Few tales were scarier to me or my classmates than this one story about four children locked in an attic for more than three years. All of them got very sick, and one of them, the youngest boy, died. Some believed that their mother and their grandmother wouldn’t take them to a doctor or a hospital. From that, others concluded that either both or just the grandmother maybe wanted them all dead. Part of the story was that the young boy might have been buried on the property. And on Halloween, there was always someone who proposed going to Foxworth, because the legend was that on that night, the little boy’s spirit roamed the grounds looking and calling for his brother and two sisters, even after the second fire. Some of my friends actually went there, but I never did, nor did Lana or Suzette, my other close friend. The stories those who did go brought back only enhanced the legend and kept the mystery alive. Some swore they had heard a little boy moaning and crying for his brother and sisters, and others claimed that they definitely had seen a small ghost.

Whatever was the truth, the stories and distortions made the property quite undesirable ever since. Since Bart Foxworth had abandoned the property, it had been quite neglected and eventually fell into foreclosure. So it was curious that someone was considering buying it. Whoever it was obviously was not afraid of the legends and curses. Bart Foxworth, in fact, was said to have believed that his reconstruction of the original building still contained evil, and that was why he left it and didn’t care to keep it up. It was said that he believed that God didn’t want that house standing. It was as though a dark cloud never left the property. People accepted the curse. Where else could you find a house with that kind of history that had burned to the ground twice? Who’d want to challenge the curse?

“Well if you want to come along, Kristin, get moving. Put on some boots and maybe a scarf. I have a lot to do there and want to get home for lunch and watch the basketball game this afternoon,” Dad said, and he clapped his black-leather-gloved hands together. “Chop, chop,” he added, which was his favorite expression to get someone moving.

My father had a construction company, simply called Masterwood, which was our last name. “With a name like mine,” Dad would say, “what could I eventually do but get involved in construction?” Masterwood employed upward of ten men, depending on the number of jobs contracted. My mother used to keep the books, but now Dad had Mrs. Osterhouse, a widow five years younger than he was whose husband had been one of Dad’s friends. I knew she wanted Dad to marry her, but I didn’t think he would ever bring another woman into our home permanently. He rarely dated and generally avoided all the meetings with women that anyone tried to arrange. For the last five years, I did most of our housework, and even when my mother was alive, Dad often prepared our meals, especially on weekends.

Right after serving in the navy, where he got into cooking, he had been a short-order cook in a diner-type restaurant off I-95. He met my mother before he began taking on side work at construction companies. She was a bookkeeper at one of them. Two years later, they married and moved here to Charlottesville, Virginia, where they both put their life savings into my father’s new company. They didn’t deliberately come here because she’d once had family here. My mother had never been invited to the Foxworth mansion, and hadn’t ever spoken to Malcolm or anyone else who had lived there. Dad said they not only moved in different circles from the Foxworth clan but also lived on different planets.

“Okay,” I said. “Wait for me.”

I ran upstairs to put on warmer clothing. I was actually very excited about going with him to Foxworth. I always thought Dad knew more than he ever had said about the original story, and maybe now, because we were going there, he would tell me more. Getting him to say anything new about it was like struggling to open one of those hard plastic packages that electronic things came wrapped in. When I came home from school armed with a new question about the family, usually because of something one of my classmates had said, he rarely gave any answers that were more than a grunt or monosyllable.

My cell phone buzzed just as I was turning to leave my room. It was Lana. In my excitement, I had forgotten about her.

“What time are you picking me up?” she asked. “We’ll have lunch at the mall.”

“Change of plan. I’m going with my father to Foxworth.”

“Foxworth? Why?”

“He has to estimate a job, and I promised I would help, take notes and stuff,” I added, justifying my going there. “Someone wants to build on the property.”

“Ugh. Who’d want to do that? It’s cursed. There are probably bodies buried there.”

“Someone who doesn’t care about gossip and knows the value of the property,” I said dryly. “It’s what businessmen do, look for a bargain and build it into a big profit.”

My father said I had inherited my condescending, often sarcastic sense of humor from my mother, who he claimed could cut up snobs in seconds and scatter their remains at her feet “like bird feed.”

“Oh. Well, what about Kane and Stanley? We were supposed to hang out with them, me with Stanley and you with Kane. I know for a fact that he’s expecting you.”

“I never said for sure, and he was quite offhanded about it.”

“Well, you never said no, and I know you liked him before when we were out. Emily Grace told me her brother told her Kane said he thinks you’ve grown into a pretty girl.”

“I’m so grateful for his approval.”

She laughed. “You like him, too. Don’t play innocent.”

“That’s all right. You never want any boy to take you for granted,” I said. “It’s good to disappoint him now and then.” She was right, though. I really wanted to be with Kane, but I wanted to go to Foxworth more. I couldn’t explain why. It had just come over me, and when I had feelings this strong, I usually paid attention to them.

“What? Who told you that? Are you reading some advice to the lovelorn or something? You’re not listening to Tina Kennedy, are you? She’s just jealous, jealous of everyone.”

“No. Of course not. I’d never listen to Tina Kennedy about anything. Gotta go,” I said. “Dad’s waiting for me. I’ll call you later.”

“Don’t touch anything there,” she warned. “You’ll get infected with the madness.”

“You forgot I had the shot.”

“What shot?”

“The vaccine that prevents insanity. It’s how I can hang out with you,” I added, and hung up before she could say another word. Besides, I knew she wanted to be on the phone instantly to spread the news. I was returning to some ancient ancestral burial ground, and surely the experience would change me in some dramatic way. They all might even become a little more afraid of me, but probably not Kane. If anything, I was sure he would find it amusing. He could be a terrific tease, which was one of the reasons I was a little afraid of him.

Laughing, I bounced down the stairs. I had my blond hair tied in a ponytail, and because of the length of my hair, the ends bounced just above my wing bones. Both my mother and I had cerulean-blue eyes, and part of the legend of the attic children was that they all had the same blue eyes and blond hair. The fact that I supposedly looked like them only enhanced the theory that I could have inherited the family madness.

I had never seen a picture of them, and Dad told me that he and my mother hadn’t, either. In fact, no one had seen any picture of them when they were shut up in the attic or even soon afterward. There were some drawings in newspaper stories, but their accuracy was always in question, as were the facts in the stories. Supposedly, the children who survived the ordeal never talked about what had happened, but that didn’t stop the tales of horror. They were always reprinted around Halloween with grotesque drawings depicting children scratching on locked windows, their faces resembling Edvard Munch’s famous painting The Scream, making it all look like someone’s nightmare. In a few weeks, those stories and pictures would appear again.

Years later, three of the children, as the story goes, returned to Charlottesville just before the second fire. Dad said neither he nor my mother had ever met any of them. Some people believed that the older sister had begun an affair with her mother’s attorney husband and that her mother was driven to madness and had actually been the one responsible for setting the first fire, which had killed Olivia Foxworth, Malcolm’s wife, who was an invalid at the time. The details remained vague, and none of the facts had been substantiated, even after the mansion was rebuilt and another Foxworth moved in many years later, which only made it all more interesting.

I could never understand it. If the story about the children locked in an attic was true, why would the children want to return to Charlottesville, let alone to Foxworth Hall? That would be like a prisoner wanting to return to his jail cell. Why revive such painful memories, unless those memories were really just the product of someone’s wild imagination? And why would her mother’s husband want to have an affair with a girl that young?

Maybe more important, why would she want to have an affair with him? No one knew where the older brother and sister were now. Some say they changed their names or left the country. The cousins who moved into the second mansion never told anyone anything, either, and even if Bart Foxworth had said something, it wouldn’t have been believed. It was like that campfire game where you whisper a secret into someone’s ear and they whisper it to the person next to them, who does the same, until the secret works its way back, and by then, the original secret is so distorted it barely resembles what the first person told.

It was like pulling teeth to get Dad to tell me anything. If I brought home another tidbit and persistently asked him about it, he would finally say, “I wouldn’t swear to any of it being true. As your mother used to say, exaggerations grow faster than mold in a wet basement around here. I told you, Kristin, forget about all that. Just thinking about it could poison your mind.”

Just thinking about it could poison my mind? No wonder the Foxworth property was an ideal Halloween hangout, populated with ghosts and moans and screams. But how could I help wanting to know more? I didn’t tell Dad about it because I knew it would upset him, but on many occasions when new kids were introduced at school or at parties, someone would say something like, “You know, Kristin is related to the famous Foxworth children on her mother’s side.”

Inevitably, the new kid would ask, “Who are the famous Foxworth children? Why are they famous?”

Then someone would go into one of the versions of the story, with everyone looking to me to tell them more. They were very skeptical when I said, “I don’t know any more than you do about it, and half of what you’re saying is surely the product of distorted imaginations.” I’d walk away before anything else could be said to me, not as if I wanted to hide anything but acting more like I was bored with the subject. Of course, I wasn’t.

Why should I be? Everyone is interested in his or her family background. It’s only natural. I’d been in many of my girlfriends’ homes for dinner when their parents brought up memories of their grandfathers and their uncles and aunts and cousins. Pictures of relatives were hanging on walls. I couldn’t imagine my mother ever putting up a picture of Malcolm Foxworth or Olivia Foxworth, not that she’d had any. She had some very old photographs of relatives, but to this day, I didn’t know who was who, and if I asked Dad about any of them, he would claim he couldn’t remember. Maybe he was telling the truth, or maybe he was just avoiding it.

Everyone’s family had black sheep, but also relatives they were proud to mention. My family background on my mother’s side had this big, gaping black hole full of terror and horror. Was it a good idea to try to fill it, or was it better just to cover it up and forget? Forgetting about it was just not very easy, at least not for me.

It was like everyone knew that your cousin many times removed was Jack the Ripper. Despite the distance in relationship, they were always looking for some sign, some indication that you carried the germ of evil. Instead of Typhoid Mary, I was Madness Kristin. Get too close to me, and you might become a blabbering idiot.

Dad was already outside checking something on his truck engine. The truck was practically a member of our family. I couldn’t remember him not driving it. When I asked him why he didn’t buy a new one instead of constantly tinkering with it, replacing parts, and filling in rust spots, he replied in one word, “Loyalty.” When I looked confused, he continued, reciting one of his favorite lectures. “Problem with the world today is everything in people’s lives is temporary. It spreads from their possessions to their relationships. They throw away their marriages as easily as they dump their appliances. This truck’s never let me down. Yes, it’s old, and it ain’t pretty, but it’s used to me, and I’m used to it.”