Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

Table of Contents

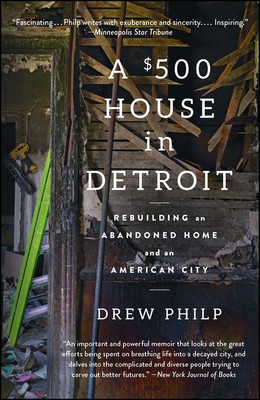

About The Book

Drew Philp, an idealistic college student from a working-class Michigan family, decides to live where he can make a difference. He sets his sights on Detroit, the failed metropolis of abandoned buildings, widespread poverty, and rampant crime. Arriving with no job, no friends, and no money, Philp buys a ramshackle house for five hundred dollars in the east side neighborhood known as Poletown. The roomy Queen Anne he now owns is little more than a clapboard shell on a crumbling brick foundation, missing windows, heat, water, electricity, and a functional roof.

A $500 House in Detroit is Philp’s raw and earnest account of rebuilding everything but the frame of his house, nail by nail and room by room. “Philp is a great storyteller…[and his] engrossing” (Booklist) tale is also of a young man finding his footing in the city, the country, and his own generation. We witness his concept of Detroit shift, expand, and evolve as his plan to save the city gives way to a life forged from political meaning, personal connection, and collective purpose. As he assimilates into the community of Detroiters around him, Philp guides readers through the city’s vibrant history and engages in urgent conversations about gentrification, racial tensions, and class warfare.

Part social history, part brash generational statement, part comeback story, A $500 House in Detroit “shines [in its depiction of] the ‘radical neighborliness’ of ordinary people in desperate circumstances” (Publishers Weekly). This is an unforgettable, intimate account of the tentative revival of an American city and a glimpse at a new way forward for generations to come.

Excerpt

Poletown, an urban prairie

I moved to Detroit with no friends, no job, and no money. I just came, blind. Nearly anyone I told I was moving to the city thought it was a terrible idea, that I was throwing my life away. I was close to graduating from the University of Michigan, one of the best universities in the world, and I was a bit of an anomaly there, too. Aside from an uncle, I’m the oldest male member of my family with all of my fingers intact, and the first in at least three generations never to have worked in front of a lathe. Growing up, I thought blue collar still meant middle class. No longer. At the university I met only one other student whose father worked with his hands.

On a sweltering day my pops and his truck helped move my few possessions into the Cass Corridor, which had been recently renamed “Midtown” by developers in an attempt to obscure the past. It was the red-light district, containing a few bars, artists, and at one time the most murders in murder city. Detroit’s major university was just up the street, skid row down the block. An ex-girlfriend who had spent time in rehab for a small heroin addiction helped me find the place. She was the only person I knew who lived in Detroit, and she left for Portland the day I moved in.

Both my father and I nervously carried what little I had into my efficiency apartment: a single pot, a bed to lay on the floor, a futon frame I’d fished from the trash and fixed with a bit of chain-link fence. My father didn’t always have the money to buy me new things, so he taught me how to fix old ones. School nights growing up were spent hunched under the sink with the plumbing, summers reroofing the garage, always right next to my father and his gentle guidance. The futon frame was a first attempt to fix something by myself. Sitting on the thing was terribly uncomfortable.

So was the move-in. If I was out of place at school, I was way out of place here. I was in one of two apartments occupied by white people in the building, which was filled with folks whom society has deemed undesirable: drug dealers, gutter punks covered in stick-and-poke tattoos, petty thieves, a thin and ancient prostitute who covered the plastic hole in her neck with her finger when she smoked. She once told me, “You’ll pawn your clothes for your nose, cuz horse is the boss of your house,” referring to heroin.

My dad locked the truck between each trip up the three flights of dirty vinyl stairs. I could sense he was uneasy—I was, too—but he never said anything aside from smiling and helping me lift my cheap necessities. Year to year, Detroit was still the most violent city in the United States, with the highest murder rate in the nation, higher than most countries in South America. My walk-up (nobody could remember the last time the elevator worked) was less than $300 a month and didn’t come with a kitchen sink. The landlord waived the security deposit if I agreed to clean the place myself.

I wasn’t quite through with school, but the wealth of Ann Arbor had become stifling. Compared with many Detroiters I was wildly privileged, but at the university I was feeling increasingly distant. I had great friends who were generous, and I felt lucky to get the education I did, but I wanted to use that for something meaningful at home. At the time more than half of UMich students were leaving the state upon graduation, and I didn’t want to be one of them.

I thought I might be able to use my schooling to help somehow. I naïvely thought, with all the zeal of a well-read twenty-one-year-old white kid, that I could marry my education with my general knowledge of repairing things and fix the biggest project, the ailing city that had loomed over my childhood, as if it were a sink or a roof. I thought I’d just be there for one summer.

The giant man across the hall from my apartment was moving out as I was moving in. He wore a green sweatshirt printed with the name of a Greektown bar where by his size I figured he must have been a bouncer. He asked if I wanted his dresser and television. I decided I could use the former. He must have sensed my unease, because as we clumsily carried the furniture into my apartment he looked me dead in the eye. He had these big beady bloodshot eyes. He whispered, “You’re welcome here,” like an incantation.

I wasn’t sure what to make of that. No stranger had ever thought to tell me I was going to be safe when moving into a new apartment.

If I was going to stay in Michigan, Detroit seemed natural. It was the most important city in the state by any measure, and in some ways it was the most important city in the Midwest. In symbolic terms, it’s maybe the most important in America. Henry Ford and Detroit had invented the modern age along with the assembly line. Then, when it was convenient, that line had turned into a conveyor belt dumping Detroit straight into the junkyard of American dreams.

At the time, I didn’t realize Detroit was just America with the volume turned all the way up, that what was about to happen would have repercussions for the rest of the Western world. Detroit was the most interesting city on the planet because when you scratched the surface you found only a mirror.

After wishing me luck my father left, and I spent that first night looking out my third-floor window. My parents were hardworking people who had followed the rules of the boomer generation, and it in turn had treated them well. They went to work faithfully, saved their money, and in the waning years of their employment had achieved a measure of middle-class comfort that was the envy of the world. What they didn’t understand was that the rules had changed and their prosperity had been mortgaged against the future. Their children would be the first American generation with less material wealth than their parents. Some of that complacent bliss they had enjoyed had been stolen, and the wars, wealth inequality, and environmental exhaustion they had allowed to go unchallenged would someday need to be repaid.

I imagined my father spent the same evening having a drink with my mother, hoping they wouldn’t be burying their son and that I’d figure out what I could do with the general studies degree I was about to be awarded, along with a steaming pile of student loan debt, about equal to the national average. Although they loved me fiercely and had given me every advantage they could afford, they couldn’t understand what I was doing in Detroit.

I spent most of those early days sitting on the stoop watching the neighborhood pass by, hoping to find a job. It seemed like everyone who could, and wanted to, had left. I wasn’t eager to begin the meaningless corporate work to pay off the tens of thousands in debt I’d accumulated, on the student loans I’d signed at seventeen before I could buy a pack of cigarettes or drink in a bar, so I stayed. At the time, moving to Detroit meant “dropping out,” in the Timothy Leary sense, to remove myself as one bolt in the proverbial machine—not as a sabot to throw in the cogs—but to get out of America by going into its deepest regions.

A few days after I’d arrived, one of the few other white kids in the building asked me to help move a television to the Dumpster. I walked into his apartment as he was shooting up.

“You want some? I have clean needles.”

I declined, but asked him if I could watch.

“Sure.”

He had just begun to tie off around his biceps, and the shot was in a syringe that he held between his teeth. I watched as he put the tip of the needle slowly into his vein at an oblique angle, his knuckles resting on his forearm. He pulled back the plunger, his blood clouding the heroin like a drop of red food coloring in a vial of vinegar. He pushed the shot into his circulatory system, like the colored acid kissing the baking soda in a science fair volcano. A great bubbling calm washed over him as he lit a cigarette. This, apparently, was going to be my new life. I rolled one myself and we smoked in silence, until he broke it.

“So you want to move that TV?”

In a scene that would repeat itself as I got deeper into the city, those kids soon left, too. In this case, they hopped trains to California and the marijuana harvest. I was the only white face left in the building.

I would get offered drugs or sex, on the street, almost daily. Buying drugs was then almost the only reason a white kid would be in the city. With nothing to do I wandered the neighborhood in boredom and was mistaken for a customer.

“No thanks, ma’am, I stick with the amateurs.”

“I’m all right, I just quit.”

“Nah, man, crack isn’t my style.”

Drinking, however, was. On Mondays the bar behind me would brew beer and the whole neighborhood would smell like baking bread. I’d never been to a bar or even a film alone, but started going there to drink by myself all night, occasionally chatting with the bartenders or the barflies, semigenius immigrants from Africa, artists working in strange materials such as pigskin, labor historians and Communists, Mexican poets, Iranian gear heads, Korean illustrators, an entire drunk UN. It made me realize there might just be more to Detroit than the death and poverty that was all I saw on the news.

The staff would often take pity on me, too, serving me free drinks or letting me stay after they switched off the neon OPEN sign. One friendly bartender drove me to the grocery store in nearby Dearborn to show me where to buy food. Until the Whole Foods showed up in 2013 there wasn’t a single grocery store chain in the city.

On my stoop I met a man named Zeno who was a crack dealer. We had little in common, but became friends out of habit and proximity, our floating schedules aligned. He had a difficult time understanding what I was doing in a place like that. So did I. But I’d learned something by facilitating poetry workshops in prisons over the previous couple of years: when you have little in common with someone and you are forced to interact, you talk about what you do have, big stuff, God and Man and War and Love. Things get deep pretty quickly and it often creates bonds not easily broken.

“Are you a cop?” Zeno said.

“What?”

“Are you a cop? Are you wearing a wire, motherfucker?” He grabbed the front of my shirt in his fist and pressed his face close to mine.

We’d been drinking pretty heavy one night and had gone into his apartment to roll a joint. He had repainted his three rooms himself, and paid the super extra to add carpet to the living room. The floors were spotless and the furniture made of dark wood. A saltwater fish tank had a pleasant blue glow and sat at the end of the small hallway, and he’d installed a chandelier over the glass kitchen table. He had created a little oasis inside the tenement. He had once told me, “Your home is your refuge. When the world outside is so fucked up, you have to have somewhere nice to come back to. Your own castle.”

“A wire? What are you talking about?”

He stared silently at me, his brow hard and aggressive.

“Take off your shirt.” He flicked the front of my T-shirt with his thumb. “If you aren’t wearing a wire take that shit off.”

“Dude, how long have you known me? What the fuck.”

I reached to get a cigarette from a pack on the table. He got to it first. He picked the pack up slightly and dropped them, his eyes never breaking contact with mine.

“Not long enough. Take it off.”

I wasn’t sure what to do next. So I took off my shirt. If there is a cool way to put your shirt back on after having been ordered to take it off by your only friend in a new town, I haven’t found it.

After that he made it his business to show me around. He took me on crack deals and to his sister’s house for dinner, introduced me to the projects, and when I said I didn’t know what Belle Isle was—our version of Central Park on an island in the Detroit River—he made me get in his car and go, right then.

As we drank forties out of plastic cups sitting on his hood, watching the sun set over the skyscrapers downtown, he told me about his life. Kicked out of school at fourteen, mother an addict, father nonexistent. To him, selling dope was more honorable than the food line. There was little to no honest work for a high school dropout, and what he’d tried—the docks, for example, were controlled by the Mob, racial hierarchy, and bored animosity—never seemed to make ends meet. So he did his work, and was good at it. He sold just enough to eat and keep a roof over his head. He never touched anything harder than marijuana and had never been in any serious trouble. He was a unicorn in his line of work.

After months of looking I managed to find a job in the most unlikely of places: the classified section of a newspaper. I met my new boss for the first time in a bar with Formica tables and moody waitresses because I was too wary to bring him to my apartment. He was a large man with an enormous voice and a black SUV just as big. He had grown up in the city, but had since moved to the suburbs to raise his kids.

He explained his company was an “all-black construction company” and he needed a “clean-cut white boy” to sell his jobs in the suburbs—people wouldn’t hire him when his address read Detroit and the first person they saw was black. I grew up in a small rural town far outside Detroit’s suburban sprawl, and knew little about the animosity between the city and the ring of municipalities that surrounded it. I didn’t know that Detroit is the most racially segregated metropolitan area in the nation.

The semester before, nearly all my classes had concerned race and were mostly filled with white people. Our discussions would tiptoe around the subject, students performing incredible verbal yoga, twisting themselves into absurdity to avoid mentioning anything that might offend anyone. I was happy to be my boss’s white face. At work we talked frankly about race. When a call would come in, we would discuss whether she sounded white or black. If she sounded white, I would bid the job. If she sounded black, my boss would.

I would also work alongside everyone else sanding floors for $8.50 an hour, plus commission if I sold a job. When I came home and blew my nose the snot would be black from sawdust and polyurethane. I worked out the summer there, hunched over a thirty-pound disk sander, a long way from the university.

In August we had a job for one of my boss’s relatives, also kin to my coworker Jimmy, a kind man with whom I worked closest and who taught me everything I know about hardwood floors. The relative’s flat was on the second story, so we had to carry the machines upstairs and the sawdust down. The homeowner had worked thirty years on the line at Ford and had lived in what he called the ghetto for most of his life, but he was proud and comfortable, in his finances and with who he was. After shaking hands and looking me over suspiciously, he showed me each gun he had hidden around his home.

“Whoa! There’s another one,” he said as he pulled something long from under the couch.

“Bam!” He mimed shooting an invisible intruder, then winked at me.

I got the sense everyone respected him, but he didn’t trust me because I was white. While we sanded and scrubbed, he apparently felt the need to work as well, and stood outside with a chain saw, cutting down tiny invasive trees that had grown into his yard, none thicker than his wrist. His adult son followed him, admonishing him to take it easy.

“Boy, I take shits bigger than you. You’re slowing me down.” He reared the saw in his son’s direction. “Now get on the other side of that tree there and look out.”

At midday, he offered to buy us lunch.

“Do you guys eat chicken?”

The crew, all black aside from me, sat bone-tired on his back steps, shrugging at the question and pulling at bottles of Gatorade. I could have passed an anatomy test on the muscles in my back.

“Now, I said I’m going to buy you lunch. Do you guys eat fried chicken?”

Jimmy answered, “Of course we eat chicken, we’re black.”

The record stopped with a scratch. Everyone looked at me. I was a vegetarian, something I had picked up at the university, as a challenge to myself. I hadn’t had any flesh of any kind in more than two years, but I hadn’t told any of my coworkers for fear of ridicule.

“I, um . . . ” I was a little too stunned to come up with what to say. I’d be breaking a pact I had made with myself. Then again, maybe I’d be exchanging it for a new one.

“He lives right around the corner. He’s black,” Jimmy said, saving me.

“I, um . . . ”

“Well, do you eat chicken?”

They all looked back at me.

“I eat chicken.”

Sanding floors showed me many areas of the city outside my bubble in Midtown and got me thinking. Maybe I could make a go of it here. Maybe I could buy a house, live in it while I was fixing it, and flip it or rent it when I moved elsewhere. They were practically giving them away. The problem was I had no idea how to buy a house, let alone fix one up. It was just a vague idea. I thought I might start with something in the vast and relatively dense residential ghettos of the city where crime ruled second only to abandonment. Or maybe in a nice historic district where proud people still raised families and mostly kept to themselves.

But first, I had to finish school, at my parents’ behest. I wouldn’t leave Detroit, not yet. I blocked my classes on two days a week so I could still work at the floor place, but $8.50 an hour doesn’t buy much gas when it’s four dollars a gallon, as it was then, so I would often hitchhike between the two cities. One time a professional gambler picked me up, going to one of the new casinos in Detroit. The houses of gambling were the latest in a long line of economic silver bullets that never seemed to make the city any less broke.

The gambler had holes in his jeans and hollow eyes. I asked him what game to play in a casino if I wanted to win. What were my best odds? He, too, looked me dead in the eye. He said, “Don’t ever walk into a casino.”

Commuting between the desperate poverty of Detroit and the cosmic wealth of the university had made me sick, gave me economic jet lag of the conscience. The explosive inequality was eating me from the inside. Detroit was among the poorest cities in the United States and located only forty-five minutes away from Ann Arbor, one of the richest. The University of Michigan, a public school, costs more to attend for an out-of-state student than the average American makes in a year. I’d begun to think of them as different worlds, and having a foot in each was taxing on my view of the country that placed them so close together, and disrupting for my love of the university that had seemed to insulate itself from the desperation just down the street.

I’d known, too, just a little bit about what it feels like to be hungry and watch someone eat. I was dangerously broke and in Detroit unsupported by the orbit of wealth at the university, where I could casually walk into a dining hall past the bored attendant for a free, stolen meal or rely on my wealthier friends to pick up the tab at the bar. I began to question if I could go back at all, sanctimony about my new home working as an antidote to my sickness of dissonance. Living in Detroit wasn’t exactly easy, but it seemed more noble somehow, and honest.

Amid the glass chandeliers and ivy of the university I had been selected to teach a class concerning race to other undergraduates, overseen by a kindly older professor named Charles. As I was getting a firsthand look at scratching out a living working near-minimum-wage jobs and the drug trade, other student teachers in the class were taking internships at places like Goldman Sachs and questionably capitalistic nonprofits in India. I thought this was bullshit and told them so. I told my teachers, including Charles, I thought academia was bullshit, too, sequestered from the real conflict. It didn’t win me many new friends. I drifted farther away from the place that four years earlier had sent me an acceptance letter that had made my father cry in front of me for the first time in either of our lives.

But Charles would often insist on taking me out to lunch. He would listen patiently to my complaints and fury as I told him of my gestating plans to buy a house. I had formulated a vague notion I would start some kind of folk school, buy a big place or a duplex and use half for instruction, half for my home. Charles, knowingly and gracefully, nodded and smiled as I laid out my dreams for changing the world. Maybe, I thought, it would start with a house. That naïve dream came one step closer when I dressed as an organ grinder for Halloween.

Just down the street from my apartment in Detroit sat a contemporary art museum that threw wild dance parties. I had concealed some cheap liquor inside the organ and set it down in the corner to dance more freely. When I took a break to retrieve an illicit swig of Old Grand-Dad, by chance, sitting next to the liquor-cabinet-cum-music-box was a white guy dressed as an organ grinder’s monkey. Something seemed meant to be.

He said he was a carpenter and his name was Will and he hated crowds, and people in general. He had just moved back to Detroit after ten years or so of traveling the States by freight train and thumb, typical methods of crusty-punk locomotion. Now he had become something different. We were both, somewhat desperately, looking for friends, both cynical about finding them.

“I kind of want to buy a house,” I told him outside the party, smoking. The crowd spilled out into the street and ignored us.

“I just did,” he said. “It’s probably burning down right now. With my dog in it.”

I called him the next week, nervous and wretched, like asking for a platonic date. He invited me over.

His house stood in a neighborhood on the near east side called Poletown. It looked like the apocalypse had descended, that the world and this life was but an afternoon performance that had reached its uneasy conclusion, the players having washed their hands and left for home, the crowd disappointed. This didn’t look like a city at all. In my tiny car I crossed a set of disused train tracks and the houses all but disappeared. Poletown seemed prairie land, a huge open expanse of gently waving grass, the sightlines broken only by what appeared as crippled and abandoned houses twisting in on themselves. Aside from the grid of roads scarring the expanse, it must have looked close to how the land had appeared when it had been stolen from the Native Americans. One of the biblical meanings of apocalypse is “New World.”

What structures remained looked like cardboard boxes left in the rain. Ominous two-story monstrosities with wide-open shells and melted porches lurched in bondage like tortured Greek gods of the underworld. Forgotten rosebushes ran over palsied fences, and the houses seemed to watch with yellowed eyes, like two-story Goya paintings, naked and ragged and proud. Trash seeped from the orifices where windows used to be. Abandoned dreams, abandoned lives, facades contorted into abandoned smiles.

Most of the houses had been deserted while still functioning. They had died by the elements, harvested clean of valuables by scrappers working as scavengers. Slow-moving nature had done the rest, reclaiming what it had lost a century ago. One of the original areas of white flight, Poletown had also been abandoned by all levels of government, the people who stayed left to fend for themselves. The average police response time was about an hour, if they came at all. Aside from some brave and stubborn holdouts and their solitary immaculate homes, the neighborhood was dead. Or so I thought.

Will’s house stood on the edge of all this, just across the tracks. His street, named for the saint of the abandoned cathedral four blocks down, was pimpled with manhole covers spewing great columns of steam from the trash incinerator looming on the horizon. In the evening the exhaling bowels of the city created an opaque curtain of fog. The only other house on the block was a hideous cinder-block project house built by an architecture student from Cranbrook, the same private college Mitt Romney attended as a teenager. Whoever built the structure apparently didn’t want to live in it either, and it, too, was abandoned, the water pipes burst from freezing long ago.

As I drove into the alley where Will parked his truck, I noticed behind his place lay a paradise of forest land abutting the Dequindre Cut, a long-abandoned railroad trench. Any homes and buildings had been torn or fallen down, and nature reigned once again. Thirty-year-old trees grew up between dumped boats and hot tubs and railroad ties and piles of rubble. A sextuple of abandoned grain silos presided over the blooming expanse of forgotten land. Scrappers would burn the jackets off copper wires at the bottom, as they were doing the first night I visited.

“The fire department will show up soon,” Will said contemplatively as I got out of my car. He sipped a can of beer and his eyes never left the silos until I walked through the fence gate made from a pallet. His yard was filled with things he’d found on walks through his neighborhood, shingles, scraps of wood, pieces of sheet metal, halves of garden tools, sad lawn ornaments. Will appeared part of the cast-off junk as well, the tired leader of a lonely circus. I got a good look at him in the light, without his monkey costume, and he was a dead ringer for Hank Williams, the same goofy resting grin, the slim ghostly figure. Had he not been moving the cigarette between his mouth and ashing on the scrubby ground, he would have looked like a mannequin, frozen in time with the forgotten things he’d collected and given a home to.

He noticed me side-eyeing at some blue 55-gallon barrels.

“Oh, I’m going to make a rain barrel system with those,” he said. He moved the pouch of tobacco from his lap. “I’ll catch the rain coming from the roof and use it to water the garden. The water bills here are outrageous.” In fact, they were. In spitting distance of the planet’s largest source of fresh water, the Great Lakes, the water bills were almost twice the national average.

Will had dragged the barrels from the market across the tracks, which was still full of working slaughterhouses. He’d squirreled them away one by one when they would appear next to Dumpsters and scrubbed some out with bleach.

“I’ll let the rain clean the others,” he said, and stood, opening his back door. The security gate was padlocked near the bottom and a cinder block served as the step up to the threshold.

“This is like a tree house, you can do whatever you want,” I said, stepping into his home.

Will demurred.

“This is great.”

“It’s not bad,” he said, his hands in his pockets.

“This is freedom,” I said.

He didn’t look so sure.

He gave me the short tour: an entryway where he kept his garden tools, to a room that held the furnace and the kitchen sink that was not the kitchen, into his kitchen piled with houseplants and mail and knickknacks. The living room was a cacophony of found objects, art he’d made by himself or presents from friends, a piano covered in trinkets and records, a rack of mixtapes he had saved over the years. His house was as full as the outside was empty.

He wound an ancient child’s toy on the piano. A tin horse and carriage ran in a circle around a saloon. The tinkly music glistened, but one of the bars was broken, rendering a sour note with each revolution.

“I found that last week out back,” he said. “This is my tool room.”

He walked across the hardwood floors and opened a creaking door. A table saw stood in the center on a platform made from logs with the bark still attached. The rest of the room was filled with dusty tools and half-finished birdhouses.

“These are cool,” I said, picking up one with an irregular shape and a tin roof. “What’s this?” I thumbed the perch, a fat nail with the number “66” stamped into the oversized head.

“It’s a date nail. You find them walking along the train tracks. It tells the year they were put in.” He took the birdhouse from my hands. “This one’s from ’66. That was a good year.”

The half dozen birdhouses in various stages of completion had all been made from junk—lath, pieces of half-burned pine, tiny sheets of metal picked from the dirt, forgotten pipe. He was making delicate houses for the free birds of the air at the same time he was building his own, nearly out of the same materials.

“I just do that for fun,” he said, shutting the door to the shop. Years later the mayor’s wife would buy one priced in the hundreds of dollars.

The house was as much Will as he was it. Walking inside was like hiking through his cluttered and brilliant mind. I would come to call this aesthetic “junk punk,” common in Detroit and rusting cities like it where the predominant vernacular was of objects cast off then repurposed and reloved by people who had been cast off themselves. The old was new again, and you needed a good eye to recognize value among chintz.

“I moved to Detroit right after high school,” Will said as I sat in a sagging armchair in the living room. He had graduated about a decade earlier than I had. “I lived downtown in a building across the hall from Kid Rock before he was famous, but never really talked to him. I moved out a couple years later to travel the country, riding the trains and hitchhiking, lived in a few cities. But I would always come home and drive the streets.”

He stroked his pit bull named Meatballs as he talked. “It was Armageddon, man! It was crazy!” His voice became excited for the first time in the evening, his sinewy frame inching closer to the edge of the seat. “I’d drive around for hours and I always noticed this house surrounded by nothing. I looked it up and it was for sale for three thousand dollars but for years, nobody had purchased it. I’d always drive by here to see if anyone had bought it. One time I drove past after I’d just broken up with my girlfriend in North Carolina and I told my roommate at the time, ‘Man, if I had three thousand dollars I would buy that house right now.’?”

His roommate happened to have received a windfall while he was gone and lent him the money that day. He purchased the house, in cash, from a Detroit police officer, the son of the former owner, and had spent the better part of the summer camping there, without much electricity or any plumbing. He bought bottled water and mopped with rainwater, planted a garden, and attempted to learn all the trades he needed to get normalcy to the house. At the beginning he didn’t even have a door, just a sheet of plywood, and would let himself into and out of his own home with a screwgun.

I pulled open a yellow window shutter behind the chair and watched: one lonely house, a lonely empty street, a lonely stoplight doing its duty for no one but us.

“This is the coolest thing I’ve ever seen,” I told him.

“Can you go with me to the hospital today?” With no warning, Zeno had called when I was in my socks making eggs.

“Of course. What’s wrong? Are you hurt? Do you need an ambulance?”

“I’m fine. I’ll tell you on the way.”

He picked me up in his blue Ford Escort, with his girlfriend, Amy, sitting shotgun. She was about half the size of Zeno, and looked shrunken that day. The hospital was only a block from my house, and we could have walked, but he picked me up and stopped in the parking garage. There was something about the formality of it all.

The three of us signed in at the desk and received “visitor” name tags to stick on our chests. We walked a short distance to a small one-room chapel in the center of the building, a dark chamber with two rows of pews and a stained-glass window behind an altar that was backlit with electric light. I sat a few rows behind and in the other aisle from Zeno in the front, who put his arm around Amy. I wasn’t exactly sure what was about to happen.

After a few moments, a fat white preacher wheeled in a small plastic gurney and parked it before the stained-glass window. I scratched at the oak grain in the pew. I wasn’t sure what I was doing here.

On the gurney lay a tiny bundle, swaddled from head to toe in a blue blanket. The child Amy had been carrying, Zeno’s unborn son, was dead, stillborn.

Zeno and I had discussed the child months ago. He told me he had gotten Amy pregnant, and although neither of the parents had the type of lifestyle that might be considered best to raise a child, they wanted to keep it. Zeno explained that living such a dangerous life, in such a dangerous place, he wanted the chance for his lineage to carry on. He might not have another opportunity for his seed to be planted, even if the soil wasn’t as fertile as to be hoped. Why wait for better days when you don’t believe there will be better days, and you don’t think you’ll live to see them anyway?

The preacher folded his hands and opened his sermon with one of the Psalms. He spoke about God and Man and Love and read from other religious books and holy works, background noise to the tiny speck of life, extinguished, lying before the altar. I don’t remember exactly what he said, but I remember Amy crying softly, and Zeno holding her, silent tears streaming down his face. Eventually Amy asked the preacher to stop.

“I want to see him.”

Oh my God.

“All right,” the preacher answered. “We usually advise against—”

“I want to see him.”

The preacher, with trembling and careful hands, removed the blue blanket from the child. Inside, wrapped in a white shroud and no bigger than half a baguette, was their son. From the back of the small chapel I could make out his tiny head and little arms and legs inside the blanket, the clear shape of a body. A dead little Moses in a plastic basket.

“I want to see his face.”

The preacher hesitated.

“I want to see him for the last time.”

I’d only been in Detroit for a few months, and this was what it was going to be like?

The preacher removed the final blanket.

The child had a stomach and delicate fingers, chubby legs. He was still and stiff and I cannot remember if he had hair, but I remember his eyes. Tiny, black, and open.

I tried to leave, meditate, anything. I imagined myself far away, outside the hospital, beyond that the city for miles and then the suburbs, the nice places and the places of peace and silences and waves and amniotic rocking and quiet. This world is a sphere, and if you go straight long enough you’ll end up right back where you were. Try as I might, I couldn’t escape those black eyes pulling me back into a reality I wanted to ignore.

The preacher covered the child.

As long as I live I will never forget the image of those black eyes.

Afterward, on the ride home, some stereo or other piece of equipment had to be sold to pay the rent. Zeno drove us to the place, and when he went inside I sat in the back of the car smoking while Amy wept softly, her head resting against the passenger-side window.

I think Zeno was trying to show me something, to warn me. Maybe it was because I didn’t know what to say, that with all my education I didn’t know how to fix it. That I couldn’t bring the baby back was a given. That I couldn’t make things feel any better, for Zeno or myself or everybody in this city and places like it, was a heartbreak. Maybe I’m projecting. Maybe I’m not supposed to say anything at all. Maybe all the tragedy of this place represented by one dead child isn’t for me, a white kid, to try to explain, that I should bow out gracefully, that this world isn’t for me and I should admit that my mistake was coming in the first place and never come back. Maybe I should have never come at all.

But I was there. I saw it. And I cannot unsee it, and I don’t know what it means, if anything. Now it’s yours, too. Welcome to Detroit.

A couple of weeks later I went alone to an art show held in a repurposed factory. I was still trying to shake off those few moments in the hospital chapel, and school was only making it worse. I knew I couldn’t go back, but now I was unsure if I could stay here either. I tried to keep busy while I decided what to do.

Past stalls filled with BDSM art and Day-Glo paintings of dead rock stars, I stopped at a booth containing dozens of bales of hay. A couple of people who seemed to shine as if they had been scrubbed with a brush for the first time in a long time chatted with pedestrians or made roses from painter’s tape.

I introduced myself to a white guy, naked under his overalls, who said his name was Garrett and the hay in their booth had been grown in Detroit. After some pleasantries, he invited me to an art show that just happened to be in Poletown, half a mile or so from Will’s. Everyone in the booth lived on a strange and special block tended by a wild and virtuous farmer who had been in the neighborhood for decades. Farm animals roamed freely and the farmer had figured out how to make hundreds of bales of hay each year in a neighborhood fifteen minutes by bicycle from downtown. The street was named Forestdale. The building holding the art show, which they were rehabbing, was named the YES FARM.

He handed me a hand-typed business card:

I thanked him and asked if I could bring a friend.

On the day of the show Will and I pulled up to the block in his little white truck. It was located within the shadow of the Packard plant, an Albert Kahn–designed factory that had come to a comfortable end as a toxic trash heap. At one time steel, sand, and rubber went in one end, and a car came out the other. Now trees grew out of the roof. It was often on fire, and people talked about it like the weather. Aside from the abandoned train station, it was the best ruin porn in the city. People hadn’t started to take high-fashion pictures of nude models in it yet, though, and there was still a notable piece of graffiti placed in the windows of the plant’s bridge, spanning Grand Boulevard.

It read, “Arbeit macht frei.”

On this block, though, all the houses seemed to be standing and well maintained, an incredible feat for a neighborhood with enough space to grow hay. Even without the fires and demolitions, gravity was inescapable. Someone had taken care of this place for a long time.

A community garden with neat little rows and a brightly painted sign sat across the street. On the corner was the YES FARM, brick, brightly painted and unmistakable. A former apothecary, the front had been painted in stencils and sunshine and brilliant waves of blue. Plywood cutouts of exotic animals had been screwed into the crumbling brick. A hole was blown into the back of the second story, which I later found out was made when a house across the street exploded, its gas line illegally hooked up with a garden hose. A wire, with what looked like an extension cord zip-tied to it, was strung between the YES FARM and a window in the house next door.

As I got out of Will’s truck, a fat brown-and-white dog sniffed at me and wagged his tail. He had a collar and nobody seemed concerned that he was just wandering around, so I shooed him away and he went to sniff in the garden. I knocked on the side door to the YES FARM, which appeared to be made from two-by-fours stacked on top of one another, old and new. I could hear music from inside and voices. I pounded again and still no answer. Will shrugged and pushed the door open.

The room was filled with construction materials and tools. The extension cord leading from the house next door was powering a few caged work lights strung across the room like blue-collar Chinese lanterns. Someone had just finished painting the room with a city scene, black buildings on a red background, primitive style. There were doors lying around and stacked against the wall, but none of them hung in the doorways. It appeared there was no heat, but there was energy. People were working on the place and it seemed this show was part of its renovation.

I stepped over a ladder and some boxes containing papers and bolts into a room filled with televisions. The first piece in the show comprised a diorama of them that had been shot with a gun, Elvis-style. The title card explained that each set was carefully selected from a mass inventory of TVs found dumped around the city and pistol-shot in the basement of the building. Another project was signed “Molly Motor” and consisted of a television that held a live rooster with straw and food, a TV terrarium. Inside was also a set of what looked to be hairy cigars, tied in a bouquet.

“What the hell is that?”

“Those are my dreadlocks. I just cut them off,” said an enormous voice from behind me. It definitely wasn’t Will.

I turned to see a woman wearing rubber boots and a Carhartt, on which someone had spray-painted a spider stencil. She reminded me of Ma Joad from Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath, a woman you would never want to fuck with and who might throttle you if backed into a corner, but with a fierce love and mothering instinct to match. She introduced herself warmly as Molly and said she lived across the street. She mentioned I could use her toilet if I needed to, and walked through the anteroom, parting a curtain into a whole new world, common in many cultures, but new to me, that of the dissatisfied and creative, the artists whose medium was society itself, those attempting, however naïvely, to make the world anew, and better this time.

I followed her in. The room was warm and neighborhood children were performing a puppet show called Patrick’s Weird Beard inside a huge cardboard television that had been constructed onstage. A half dozen kids in homemade costumes were giggling and stumbling through the show of their own creation. The small room was packed and the lights had been dimmed. The fire in the wood-burning stove was raging and you could hear its roar in the silences. I found Garrett in the crowd and slid in silently next to him. He whispered that earlier in the night they had hosted a City Council candidate who gave a speech inside the TV. He was a dark horse, and had just gotten out of prison, but seemed to make a big impression. Garrett also mentioned I could use his toilet if I needed, because the one in here had frozen.

After the play the lights were turned up and everyone milled around in conversation. There were about thirty people in the room, most of them in different states of dirty, but none of them filthy—it was like the healthy glow and smell you get after taking a run, not the kind of funk when you’re lazy and haven’t showered in a week. This dirt was from work.

The children scurried among all manner of art made from TVs, grabbing food off the tables, continuing their puppet show offstage, laughing. Garrett pointed out the farmer, Paul, in a pair of coveralls, who had grown the hay. He was skinny with a neatly trimmed gray beard, and was drinking a can of beer, talking with a red-headed black boy. He had a wiry, electrical energy, and scurried away before I could introduce myself. He seemed important, revered even, someone with an entire spinning globe of knowledge inside his hyperactive head, a leader of a leaderless tribe. Who was this man with a tractor and hay and a block of diverse people in East Detroit?

I asked about the TVs. Garrett said this show was called the TV Show, and the irony of it was that almost no one in the room owned a working one. He said everyone from the block had been pitching in to get the building functioning just enough for the evening.

He pointed out a new mural that had just been painted, a mother-earth green figure growing too big for the wall and onto the ceiling with doleful eyes and huge feet. The artist who had painted it sat beneath the picture on a reclaimed church pew with his wife. She was intensely pregnant.

“That’s his unborn son he painted,” Garrett said. “He’s about ready to burst from Erin’s stomach. He’ll get raised in Detroit, right here on the block.”

I realized the room and this block were the incarnate vision of a philosopher I had read in college, then living just a few blocks away and more than ninety years old. Grace Lee Boggs was Detroit’s patron saint of transformation, the spiritual center of almost anything truly innovative in the city. Although difficult to pinpoint exactly, her fingerprints touched many communities like this, striving for a new image of possibility. I had found an idea made manifest.

Busy introducing me to everyone, Garrett forgot to tell me about himself. When I asked, he said he had moved around some, but had come from an art colony in San Francisco that had just been gentrified out of the Mission. Originally from Boston, he was trying to decide if he was going to make a go of it in Detroit or just keep wandering the polluted and harried cities of America’s urban wasteland. Not liking to talk about himself, he quickly introduced me to more people whose names I immediately forgot, but stopped at a slight woman who had painted a picture of two hands stretching a tape measure that hung over the doorway. Garrett introduced us and we shook hands. Her daughters had been two of the children performing the play.

“Hi! I’m Kinga!”

We were interrupted by a ghoulish guitar chord from the stage. A tall and tattooed man sat behind the drums, and a redhead I recognized from the last art show manned the guitar. It appeared the final order of business was a jam involving anyone who wanted to play.

“That’s Andy, Kinga’s husband, behind the drums,” Garrett shouted into my ear.

“Do you play?” Kinga yelled to me on her way to the piano.

“Sure.”

I grabbed a guitar, and much of the neighborhood was onstage, more than a dozen people, adding their little sounds, working on one more thing as a community before the night was through. The rest sat in the audience, clapping and hollering and drinking. Andy sang into a microphone:

Nobody can unplug my drums

That’s why I’m beatin’ ’em

And no one can unplug the sun . . .

I sold my car and bought a truck for $1,000, a rusted F-150 built when I was still in elementary school. That birthday, my twenty-second, I asked my parents for a power tool set that included a reciprocating saw, circular saw, drill, and flashlight. I thought leaving would be turning my back on everything that dead baby boy represented, and I needed something to keep me in Detroit, keep me from running away. I was going to try to buy a house and I was hoping Forestdale could show me how to build it into a home.

My father was excited that I wanted to do something befitting a man. While he and the rest of my family had been building things, I had been writing poetry. This was something he could understand. Wisely, he had bought me a single tool each Christmas since I was a toddler, so I already had many of the basics, screwdrivers, wrenches, and such. He was happy to oblige with more of the same.

Will said I could live for free at his house that summer, but no longer. He was a private man.

Aside from a single paper, all that was left of school was to graduate. The essay was for Charles, the kind professor who would take me to lunch. It concerned that dead baby. I was angry and hurt, both at myself and my peers, who I thought were leaving their posts at the most crucial point. The paper was dramatic and not particularly self-aware. I was slashing with a knife of self-righteousness at anything near me, including potential allies. Maybe I needed to do it to leave both behind, Zeno’s raw world of the drug trade and tenements, and Charles stifling, pretentious world of circular and hopeless discussions at the university. I was looking for something far more meaningful than either, something closer to the American heart. In lieu of a grade for my paper, Charles gave me this response:

My guess, based again on my own struggle (projection?), is that you feel empathy and horror for the pain you see in Detroit, and that you feel revulsion at the comfort you see in Ann Arbor. That you may also feel drawn to Detroit as a way not only to support the people there, but also to work out your own personal anger. That your anger sometimes frightens you, because you do not want to lose the love and acceptance of the people you are angry with. That you feel panic sometimes because, despite your good intentions, you feel helpless to do anything about the social conditions that you see . . . That you deeply, desperately want to create change, and that you do not really know how to take effective action. That “dropping out” seems the only alternative, but an ineffective one. That you feel deep confusion about who you are and what your identity is in all this mess. That you feel excited by possibility, and deeply sad and lonely. That what you really want in an ally is someone who can see not only your courage and ideals but also your fear, loneliness, and shame.

Product Details

- Publisher: Scribner (April 10, 2018)

- Length: 304 pages

- ISBN13: 9781476797991

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

“In this impassioned memoir, a young man finds a community flourishing in a city so depopulated that houses are worth less than a used Chevy.…Philp ably captures the frontier feel of Detroit as he laboriously rehabs his ruined house from foundation to roof. His homebuilding narrative is engrossing….The book shines [in its depiction of] the ‘radical neighborliness’ of ordinary people in desperate circumstances.”

—Publishers Weekly

“[Philp] quickly becomes an involved resident, using creativity, resourcefulness, ingenuity, and positive thinking to create a place for himself in a depressed city…highly recommended for general readers interested in the history and resurgence of Detroit and other U.S. cities.”

—Library Journal

“Engrossing…Philp is a great storyteller, and he has done a good job of documenting his struggles to carve out a home. It’s also easy to see why he intends to stay.”

—Booklist

“[A] deeply felt, sharply observed personal quest to create meaning and community out of the fallen city's ‘cinders of racism and consumerism and escape.’ Philp ably outlines the broad issues of race and class in the city, but it is the warmth and liveliness of his storytelling that will win many readers. A standout in the Detroit rehab genre.”

—Kirkus Reviews, starred review

“Lots of young bohemian types are fascinated by Detroit—land of the fabled $500 house!—but few take the plunge as headily as Drew Philp did, not only buying his own place but renovating it from the inside out, getting to know the neighbors, and learning about one of America's most fascinating cities as only a true resident can. Philp writes about his experience with sensitivity, humility and humor, and his voice is a necessary addition to the literature of the Motor City.”

—Mark Binelli, author of Detroit City is the Place to Be

“Downright eloquent and deeply moving. Beyond the sheer, compelling force of Philp’s writing, his account is insistently honest and full of insight. No shortcuts. No unrealistic fantasies. No pretenses of the sort that made my nerves twitch before I gave up on the literature of Nightmare Detroit. Philp the 23-year-old kid comes alive convincingly, in all of his confused but determined effort to rebuild a house and sink roots. He captures the city in all of its horrors and hopes, contradictions and blind faith.”

—Frank Viviano, eight-time Pulitzer Prize-nominee, and National Geographic writer since 2001

“An important and powerful memoir that looks at the struggles and great efforts being spent on breathing life into a decayed city, and delves into the complicated and diverse people trying to carve out better futures.”

—New York Journal of Books

“A fascinating inside look….Philp writes with exuberance and sincerity....Inspiring.”

—Minneapolis Star-Tribune

“Philp, the 23-year-old, recent college graduate, begins with a carcass, and over time constructs a house that becomes the prism through which he determines not only his place in the world, but also what he wants out of life. A reader can’t help but finish the book and begin asking themselves the same questions.” —Los Angeles Review of Books

“Philp’s book gives us a glimpse of a world saved not by trying to do the right thing. But of doing the right thing because we have worked to transcend our differences and to know and care for each other across all the lines—including the lines between our backyards.” —Colin Beavan, YES! Magazine

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): A $500 House in Detroit Trade Paperback 9781476797991

- Author Photo (jpg): Drew Philp Photograph by Garrett MacLean(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit