Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

LIST PRICE $10.99

PRICE MAY VARY BY RETAILER

Free shipping when you spend $40. Terms apply.

Buy from Other Retailers

Table of Contents

About The Book

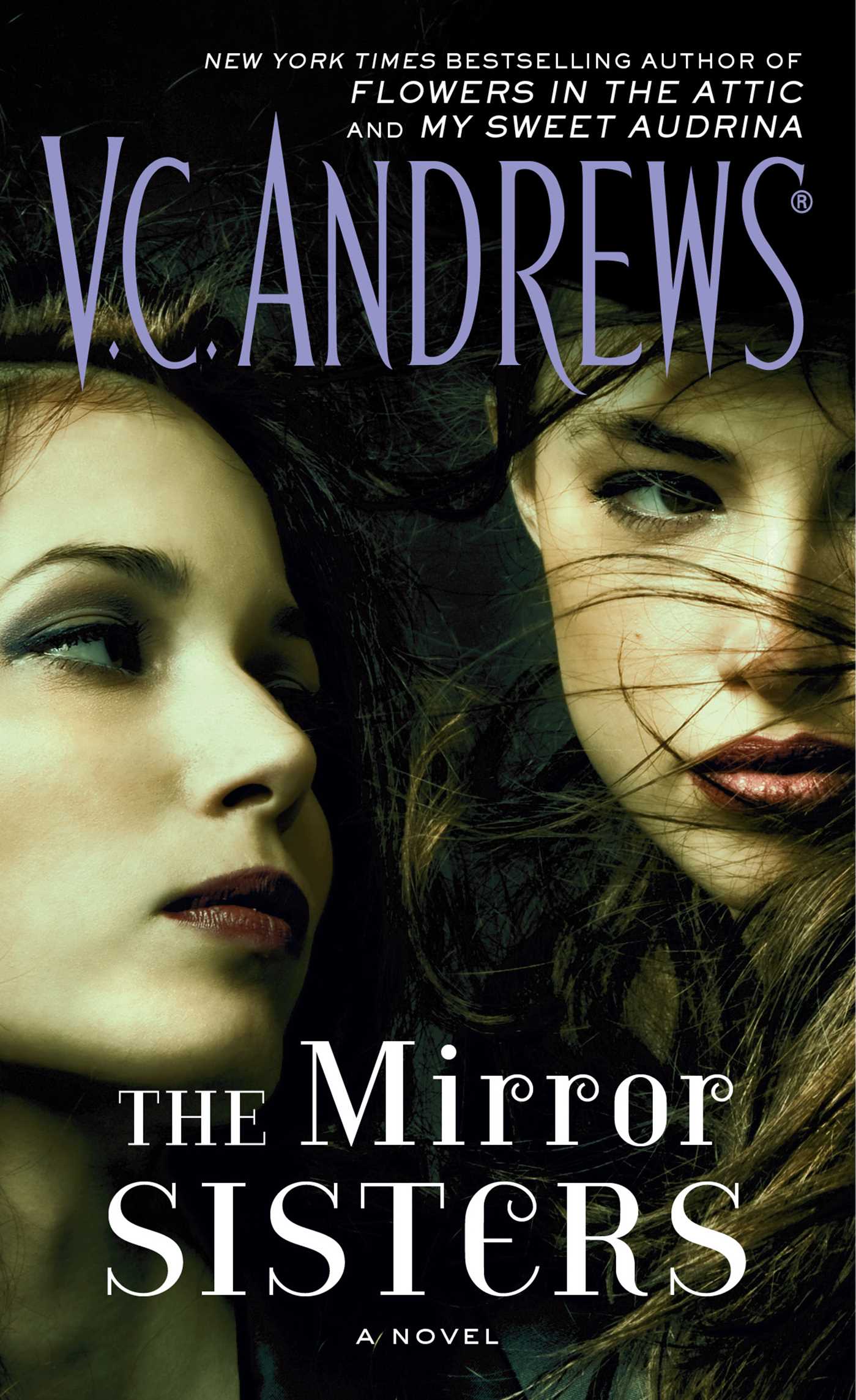

From the legendary New York Times bestselling author of Flowers in the Attic and My Sweet Audrina (now Lifetime movies) comes the first book in a new series featuring identical twin sisters forced to act, look, and feel truly identical by a perfectionist mother. For fans of Ruth Ware (The Woman in Cabin 10) and Emma Donoghue (Room).

Alike in every single way...with one dark exception.

As identical twins, their mother insists that everything about them be identical: their clothes, their toys, their friends...the number of letters in their names, Haylee Blossom Fitzgerald and Kaylee Blossom Fitzgerald. If one gets a hug, the other must too. If one gets punished, the other must be too.

Homeschooled at an early age, when the girls attend a real high school they find little ways to highlight the differences between them. But when Haylee runs headfirst into the dating scene, both sisters are thrust into a world their mother never prepared them for—causing one twin to pursue the ultimate independence. The one difference between the two girls may spell the difference between life...and a fate worse than death.

Written with the taboo-breaking, gothic atmosphere that V.C. Andrews is loved for, The Mirror Sisters is the latest in her long line of spellbinding novels about mysterious families and tormented love.

Alike in every single way...with one dark exception.

As identical twins, their mother insists that everything about them be identical: their clothes, their toys, their friends...the number of letters in their names, Haylee Blossom Fitzgerald and Kaylee Blossom Fitzgerald. If one gets a hug, the other must too. If one gets punished, the other must be too.

Homeschooled at an early age, when the girls attend a real high school they find little ways to highlight the differences between them. But when Haylee runs headfirst into the dating scene, both sisters are thrust into a world their mother never prepared them for—causing one twin to pursue the ultimate independence. The one difference between the two girls may spell the difference between life...and a fate worse than death.

Written with the taboo-breaking, gothic atmosphere that V.C. Andrews is loved for, The Mirror Sisters is the latest in her long line of spellbinding novels about mysterious families and tormented love.

Excerpt

The Mirror Sisters 1

There was nothing Mother worked harder at than keeping us from differing from each other, even in the smallest ways. From the day we were born, she made sure that we owned the exact same things, whether it was clothes, shoes, toys, or books—we even had the same color toothbrushes. Everything had to be bought in twos. Even our names had to have an equal number of letters, and that went for our middle names, too, which were exactly the same: Blossom. I was Kaylee Blossom Fitzgerald, and my sister was Haylee Blossom Fitzgerald. That was something Mother had insisted on. Daddy told us he hadn’t thought it was very significant at the time, so he’d put up little argument. I’m sure he regretted it later, as he came to regret so much he had failed to do.

Although neither of us had the courage to complain about our names, we both wished they were different. By the time we were sixteen, Haylee had gone so far as to tell people she had no middle name. When anyone looked to me for confirmation, I agreed. That was one of those little ways Haylee gradually got me to oppose things Mother had done. I was the reluctantly rebellious twin practically dragged by my hair into the fiery ring of defiance.

Actually, when I think about it, we were lucky to have two different first names. We couldn’t be Haylee One and Haylee Two or Kaylee One and Kaylee Two based on who was born first, either. Mother would never tell us who was first, and Daddy hadn’t been in the delivery room. He’d been on a business trip. I don’t know if he ever asked her which one of us was born first, but I doubt she would have told him anyway. She’d pretend not to know, or maybe she really believed we were born together, hugging and clinging to each other with our tiny pink hands and arms as we were cast out of her womb and into the world, both of us harmonizing in a cry of fear. Whenever Mother described our birth, she always said that the doctor practically had to pry us apart.

“I thought there was only one of you at first. That’s how in sync your cries were. One voice,” she would say, and she’d look starry-eyed, with that soft smile of wonder that fascinated both Haylee and me when we would sit on the floor in front of her and listen to the story of ourselves. As we grew older, she wove the magical fabric in which we would be dressed, wove it into a fantasy about the perfect twins. There was one rule that if broken would bring about disaster: we had to be loved equally, or some dragon monster would destroy our enchantment.

Daddy wasn’t anywhere nearly as obsessed about treating us equally in every way. There was never a doubt in my mind that it was something he believed Mother would grow out of as we grew older. He humored her with his smiles and nods and especially with his favorite response to what she would demand: “Whatever you say, Keri.”

He admitted that he was excited about having twins, but at first, he didn’t see any additional burdens that other parents of more than one child had. Even as very small children, we could see that he was nowhere as uptight about it, which only infuriated Mother more. During our early years, if he forgot and bought something for me and not for Haylee, or vice versa, our mother would become so upset that, in a violent rage during which I would swear I felt a whirlwind around us, she would tear up or throw out whatever he had bought. Haylee felt the whirlwind, too, and, watching Mother, we would cling to each other as tightly as we supposedly had the day we were born.

There was simply no excuse Daddy could use for what he had done that would satisfy her. For example, he couldn’t say one of us liked a certain color more or was more interested in something and he had just happened to come upon it during his travels, like someone else’s father. Oh, no. Mother would look as if she had accidentally put her finger in an electric socket and would tell him he was wrong and had done a terrible thing.

In his defense, he pleaded, “For God’s sake, Keri, this isn’t a capital offense.”

“Not a capital offense?” she fired back, her voice shrill. “How can you not see them for what they are?”

“They’re little girls,” he declared.

“No, no, no, these are not just two little girls. These are perfect twins. They see the world through the same eyes, hear it through the same ears, and smell it through the same nose.”

He shook his head, smiling but concerned. I looked at Haylee. Was Mother right? To anyone watching us, it did look as if we liked the same foods, the same flavor of ice cream, the same candy. It was true that when we were very young, anything one of us liked, the other did, too, and anything one of us hated, the other hated. Maybe we felt we were supposed to or we would lose our mystical powers. Nevertheless, Mother was shocked Daddy didn’t realize that.

“I think you’re exaggerating,” Daddy told her.

“Exaggerating? Are you in the same house, Mason? Do you see your own children?” she asked him in what, even as a young girl, I thought was a terribly condescending tone. She sounded more like she did when she chastised us.

Mother also had a habit of smacking her right fist against her right thigh when she started her responses to things that upset her this much. Sometimes, she did it so hard that both Haylee and I would flinch as if we felt the blows. After one of her more dramatic outbursts, I saw her thigh when she was getting ready to take a shower. It had a bright red circle where she had pounded it. Later it turned black-and-blue, and when Daddy mentioned it, she said, “It’s your fault, Mason. You might as well have struck me there yourself.”

Finally, Daddy always managed to stammer an excuse, but he still couldn’t ever get away with “I’ll buy the other one something tomorrow.” Whatever it was that he had bought one of us and not the other, it was gone that day, no matter what he had promised. Sometimes he would take it back and have his secretary return it to the store, but most times, after Mother had destroyed it or thrown it out, he would go back when he could and buy two this time, so he could give both of us whatever it was he thought one of us had wanted. He never looked happy about it. That satisfied Mother, though, and brought what Daddy called “a fragile armistice where we tiptoed on a floor of eggshells.” We were all smiles again. Our pounding hearts relaxed and the electric sizzle in the air disappeared, for a while anyway.

In our house, stings, burns, and aches ran around just behind the walls and just under the floors like termites. Haylee and I were in the center of continuous little tornadoes. Sometimes I thought Haylee did things deliberately so she could see these storms brew between Daddy and Mother. It was one of the differences I sensed early between us. Haylee had an impish delight in causing little explosions between our parents.

But she was far from the main cause of it all in the beginning. It wasn’t difficult to understand why this turmoil was happening around Haylee and me. In our mother’s mind, a minute after we were born, all thoughts about one of us had to be about the two of us simultaneously. She claimed it was practically blasphemous to do otherwise, because the biggest danger for any parent of identical twins was that somehow, some way, he or she would favor one over the other and destroy the confidence of the one not favored.

It was one thing to praise one of your children because he or she had done something spectacular. Everyone knew stories about fathers who favored one son over another because he was a hero on the football field or got good grades. The same was true for a daughter who might please her mother more by being more responsible, being talented in music or art, or maybe just being prettier.

But none of this could apply to identical twins, not in our mother’s way of thinking.

According to Mother, Haylee had no talents that I didn’t have, and I had none that she didn’t have. Certainly, neither of us could be prettier than the other. Our voices were so similar that people never knew which one had answered the phone. Even Daddy was confused sometimes when he called. There was always a question mark in the air first. “Haylee? Kaylee?”

When we were a little older, Haylee often pretended to be me on the phone. I think she worried that Daddy liked me more and wanted to see how he would speak if he thought I was the one answering the phone. I suspected he did like me more than he liked her, and she knew it. Once she said, “If he doesn’t know which one of us it is, he’ll say your name because he hopes it’s you.” I didn’t know if she was right. I didn’t keep as close a count as she did.

Maybe it was simply because he wasn’t around us as much as he should have been, but if I suddenly came upon him while he was reading or if Haylee did, Daddy would look at whoever it was, and his eyes would blink for a moment as his mind settled on which one of us was there. Anyone could see that he was struggling with it because Mother had him terrified about calling me Haylee or calling her Kaylee. Mother insisted that he must know which of us was which.

After all, how could our own father not know us? He agreed, and when he did get it wrong, he blamed himself for not concentrating or paying attention enough. However, he admitted that there were times when he was actually mistaken even though he was concentrating.

“They’re so alike!” he cried, hoping to be excused when Mother blew up at him for it, but all that did was prove her point and make her even more obsessive about how we were supposed to be treated.

“Of course they’re so alike. That’s always been my point. You have to try even harder, Mason, and be more careful about it,” she told him. “You never liked it when your father called you by your brother’s name, and you weren’t even twins. He is two years older than you are, but how did you feel, Mason? Go on, confess. You felt he was thinking more of him than he was of you, right?”

Daddy had admitted that to her once, so what could he do but retreat with the look of a punished puppy? I always felt sorrier for him than I did for us. Sometimes I pretended I was Haylee if he called me that, just so he would get away with it, but if Mother was there, that was impossible. She never made a mistake. I never knew why not, except to think that it was true that mothers knew their children better.

There were so many rules of behavior toward us that Mother laid down, with the power and importance of the U.S. Constitution, our own Ten Commandments:

Thou shalt not call Haylee “Kaylee,” or vice versa.

Thou shalt not buy one a gift you do not buy the other.

Thou shalt not take one somewhere and not the other.

Thou shalt not kiss one without kissing the other.

Thou shalt not hug or hold the hand of one without hugging or holding the hand of the other.

Thou shalt not say good morning or good night to one without saying it to the other.

Thou shalt not ask one a question you do not ask the other.

Thou shalt not introduce one to someone without introducing the other.

Thou shalt not tell one a story without telling it to the other.

Thou shalt not smile at one without smiling at the other.

Because of all the rules, I often thought our house was more of a laboratory than a home. I think Daddy did, too. Even Haylee admitted to feeling as if we were under observation in a glass bubble while strange new experiments on bringing up identical twins were being conducted. Many of Mother and Daddy’s friends often also seemed to believe that. I once heard someone whisper that maybe Mother was giving reports to a special government agency. I know that, like me, Haylee felt this all made us seem strange to anyone who witnessed our upbringing. There were other twins in our community, even on our street, but they were not identical, and they seemed no different from kids who had no twins. They were permitted to wear different clothes and do different things, and their mothers weren’t so uptight about potentially devastating personality complexes.

But our mother would point or nod at them and say, “Look how competitive their parents have made them. They enjoy making each other feel bad. You’ll never do that,” she would add with a confident smile. “You will always consider each other’s feelings first.” She had no idea about what was coming, crawling along on the tails of shadows toward our home and our family as we grew older.

It was difficult, if not impossible, not to feel that we really were unique, and not just because we happened to be identical twins. Haylee liked to think we did have special powers, and for a long time, I believed it, too. We looked so alike that we could pretend we were looking in a mirror when we looked at each other. In fact, we rehearsed facing each other and moving our hands to points of our faces as if we were looking into a mirror. Mother’s friends would roar with laughter, and Mother would look very proud when she had them over for a lunch during our younger years.

“They’re so perfect,” she’d whisper, her eyes fixed on us. “So perfect, down to every strand of hair.”

She would seize our right hands and turn them up so others could see our palms and then say, “Look at the lines in their hands, how exact they are in depth and length. Not all identical twins are this exact,” she’d explain.

Both of us did have some sense of difference simmering inside, though, and it grew stronger, of course, as we got older, despite Mother’s efforts to smother it. It was destined to boil over, but in Haylee before me. Mother seemed unable to imagine that. She was so confident that she was right about how we would grow up and treat each other.

I was convinced that she truly believed that Haylee and I had the same thoughts simultaneously. If one of us asked her a question, she would immediately look at the other’s face to see if the same question was on her mind. Whether it was or not, she assumed it was. Daddy never did, but she was quick to point out how we both laughed at the same things on television and looked sad at the same sad things and wondered about the same things.

“Remarkable,” she would say in a loud whisper.

She often surprised us like that, commenting on some ordinary thing we had done together and giving us the feeling that it wasn’t ordinary after all. Daddy would look at us again to see what she saw. Sometimes he would nod, but most of the time, he’d shrug and say, “It’s not unusual, Keri. Kids are kids,” and he’d go on reading or doing whatever he had been doing. More than once, I caught Mother smirking at him with great displeasure when he did that.

I often wondered why Daddy didn’t think we were as special as Mother thought we were. Did that mean he loved us less? Why wasn’t he as afraid of any differences we might show? In fact, whenever he could, especially when Mother wasn’t watching or listening, he encouraged them, and because of that, Haylee loved him more. But I never believed he loved her more than he loved me, which was what she often claimed.

It wasn’t easy for him to applaud our differences. Keeping us similar was so important to Mother that we were hardly ever alone when we were very young. It seemed she was always there hovering over us, watching carefully, eager to pounce as soon as one of us began to do something different from the other. If I reached for a cracker and she saw me do it, she would hold the box out to Haylee, too.

“I don’t want one,” Haylee would say.

“You will in a moment,” Mother would tell her, as if only she could know what either of us really wanted. It didn’t matter if Haylee wanted one just then or not. She was getting one because Mother insisted.

If Daddy was present, he would say something like “Why don’t you just let them eat when they’re hungry, Keri?”

“She’s hungry,” Mother would reply. “I know when she’s hungry, Mason. Do you cook for them? Do you know what they like and don’t like?”

He’d put up his hands like a soldier surrendering.

The same rule applied to me if Haylee reached for something or wanted something, but I saved trouble by reaching for it, too. As soon as I did, Mother would smile at me, her worried face opening like clouds parting for the sunshine.

“See?” she would say if Daddy was there.

Haylee often noticed how pleased Mother was with me and looked upset. It was as though she was keeping track of how many times our mother smiled at each of us, adding up the points we earned to prove whom Mother would eventually love more. I tried to impress her with how important it was to Mother so she wouldn’t think I was doing it to make her look bad or to make myself look better, but Haylee never believed me.

“You want her to love you more, Kaylee. Don’t say you don’t,” she told me.

Maybe I did, but I knew Mother wouldn’t let herself do that. She was too strict about how she interacted with us.

I claimed I remembered Mother changing my diaper whenever she had to change Haylee’s and her doing the same for Haylee whenever she had to change mine. Maybe it was something Daddy had told us, but the images were very vivid. It still seemed to be true as we grew out of diapers. Neither of us could wear anything fresh and clean if the other didn’t. If Haylee ripped something of hers and Mother was going to throw it out, she’d throw out mine along with it. Haylee often got her clothes and shoes dirtier than I got mine, but mine were always washed along with hers anyway.

How many times did Haylee have to eat when I was hungry, and how many times did I have to eat when she was hungry? It got so we would check with each other in little ways before crying out, reaching out, or even walking in one direction or another. If Haylee wasn’t ready to go or to do something, I didn’t, and the same was true for her. We both knew instinctively that it was the only way we could protect ourselves from doing things we didn’t want to do.

Mother didn’t realize that we were doing this deliberately or why. Instead, she would always point out our mutual requests and actions to Daddy to prove her theory that we were unusually alike.

“Don’t you see? Can’t you see how remarkable they are?” she would ask, frustrated at how calmly he took it all in. He’d shrug or just say, “Yes, remarkable,” but I could see he wasn’t as convinced about it as she was. Maybe he saw how she was often causing us to do things simultaneously, but he hesitated to question her about it, even though I could see him scrunch his face in disapproval. Sometimes he tried to be humorous about it and say something like “Hey, Keri, guess what? They only need one shadow.” He’d laugh after he had said something like that, but she never laughed at his jokes about us and soon he stopped trying.

He never really stopped complaining, though. I remember Daddy claiming that I was able to stand and walk long before Haylee could but that Mother wouldn’t let me. He said he suspected she would push me down to crawl until Haylee took her first steps. Then, and only then, would she announce our progress to him.

Once, when they were arguing about us, I overheard him tell her that he had seen her breastfeeding many times, one of us at each breast and stopping if one was satisfied, no matter how the other cried.

“It has nothing to do with hunger. You don’t know anything when it comes to that sort of thing, Mason. You’re just like any other man.”

But from the way he kept questioning her about things she had done with us, I could tell he was growing more skeptical. None of that mattered to Mother, though. She would act as if she didn’t hear what he was saying. Once he dramatically turned to the wall and complained, but she ignored him and didn’t laugh at all. For Daddy, it was like being on a boat that was sailing toward a storm in the distance but being unable to change direction.

There were just too many things Mother would do with us that annoyed him. Eventually, he complained more vigorously about things that he thought were more serious. If Haylee or I had a cold, she always gave cough medicine to both of us. Daddy objected loudly to that, but Mother assured him that whichever of us seemed fine would soon catch the same cold. “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure,” Mother declared.

Often, Haylee would begin to cough when I did, but I couldn’t help suspecting that she was just imitating me to make Mother happy and earn those love-me-more points.

“Don’t you see what a wonder they are?” Mother would say to Daddy when he didn’t react enough to please her after she had told him about something we had done together. Nothing seemed to frustrate her more.

“They’re a wonder to me no matter what,” he would say, but she would shake her head as if he was too thick to understand.

Sometimes he would try to seem more excited just to please her. Then he would reach to hug us. I saw how he always looked to Mother first so she would see that he was going to lift us both, hold us for the same amount of time, and not favor one of us over the other with his kisses and hugs. That pleased her. She would smile and nod as if he had passed some sort of test. Keeping the peace was obviously the most important thing to him, even more important than standing up for Haylee or me if either of us did something different, something original.

When I was old enough to understand him more, I realized that he wanted his home to be a true sanctuary, a place he could come to in order to escape the pressures and conflicts he had to endure in his work. Sometimes when he came home and I was there to see him first without him knowing, I would see him close his eyes and take a deep breath, as if he had finally reached fresh air. No wonder he let Mother get away with as much as she did when we were younger.

Of course, we had been too young to know what they said about us when they were alone, but later, when we were older, I understood that right from the beginning, Mother often instructed Daddy about how we were to be treated, especially how he was to talk to us, hold us, walk with us—in short, love us. Loving your children was supposed to be something that came naturally to a father or a mother. It wasn’t something that had to be taught. I knew he thought this, but he never came out and said it, at least not in our presence.

Daddy never stopped trying to get Mother to loosen up when it came to us. For our first birthday and every one thereafter, Mother made us each a cake so we would have the same number of candles and one of us wouldn’t blow out more candles than the other.

“Don’t you think you’re carrying this too far?” Daddy would ask from time to time, especially about the birthday cakes. That could set her off like a firecracker and threaten to ruin our birthday celebrations. Those hands of surrender would go up, and he would step back like someone asked to step off the stage and become simply an observer, maybe a student in a class on how to treat special twins.

In fact, when we were old enough to understand some of what she was telling him, we would also listen at the dinner table or in the living room when she was reading to Daddy from books about bringing up identical twins. She did sound like a teacher speaking to a student. It wasn’t as clear to us when we were very young that she was talking about us, of course. Sometimes, even after we realized it, it still felt as if she was talking about other children. We would sit there listening and when she paused, Daddy would look at us closely as if to confirm that we were the girls she was describing.

I shouldn’t have been surprised at how accommodating Daddy was when it came to her instructions regarding us. It wasn’t easy for anyone to challenge her. Mother was an A-plus student in high school and college. Like Daddy, she had graduated with honors. When they first met, he was majoring in business, and she was heading to law school. Daddy admitted that no one could research anything better than our mother. That’s why she would be a very good lawyer. In those early days of our upbringing, she simply overwhelmed him with facts, statistics, and psychological studies of children. She’d hand him the books or the articles she had culled and tell him to read them for himself.

“That’s all right, Keri,” he would say. “I’ll take your word for it. I’ve got plenty to read as it is.”

Even so, I caught him gazing at articles from time to time, reading the sentences Mother had underlined. She left them around the house deliberately, I thought, especially near where he sat. When I was older, I tried to read them, too, but Haylee thought they were boring. After all, they didn’t have her name in them. Mother knew Daddy was glancing at them at least and would make references to them when he started to question something she was doing. It was enough to stop him, even in mid-sentence.

However, they weren’t always arguing about us. No matter what Daddy really thought about how she was raising us, both Haylee and I were always impressed with how much Daddy respected Mother and how much she admired him, at least when we were younger. When she wasn’t angry at him for something, she treated him as if he were a movie star who just happened to be living in our house. He was a handsome, light-brown-haired, athletic six-foot-one-inch man with what Mother called “jewel-quality crystal-blue eyes, eyes that help his smile stop clocks.”

I didn’t understand what that meant, and when I didn’t understand something, Haylee certainly didn’t, either, although most of the time she would pretend she did just to make Mother happy and pile up those love-me-more points.

“How could a smile stop a clock?” I asked.

“Yes, how could his smile stop a clock?” Haylee quickly repeated. She didn’t like me being first with anything, especially questions.

“It means he is so stunning that even time itself has to pause to appreciate him,” she explained, but we both still had puzzled expressions on our faces.

Haylee looked at me, worried that this had helped me understand but not her. It hadn’t. We were too young yet, but Mother didn’t elaborate any further, except to say, “That’s why I fell in love with him. I was always very particular about boyfriends.” She laughed and kissed us and said, “Don’t worry. Someday you’ll know exactly what I’m saying. Both of you will have lightbulbs go off in your heads simultaneously.”

That was her big word for us, simultaneous.

Everything we did had to be done at the same time, and she literally meant the exact same moment. She was so positive about this and made it so important to us that we both worried that we were doing something terribly wrong if one of us did something without the other, even when she wasn’t watching us.

“I’m warm,” I might say, and indicate that I was going to take off my sweater. I could see Haylee thinking about it. Even if she wasn’t warm, too, she would nod and start to take off hers. And the same was true for me whenever she began to do something I hadn’t thought of doing. If Mother happened to see this, she would smile and kiss us as if we had done something wonderful.

“My girls,” she would say. “My perfect twins. Haylee-Kaylee, Kaylee-Haylee.”

Were we really perfect? In the beginning, Haylee liked to believe it, but gradually, as we grew older, Mother let go of “my perfect twins” and replaced it with “my perfect daughter,” which made it sound as if we were halves of the same girl.

It was reasonable to accept that every young girl would want her mother to believe that she was perfect. What Haylee never understood was that it was true for every mother except ours. Ours didn’t see one of us as perfect without the other.

How sad and troubling was the realization that substituting one word, daughter for twins, would bring about so much pain and unhappiness for Haylee and me.

And eventually, even for Mother herself.

But by then, it was far too late.

There was nothing Mother worked harder at than keeping us from differing from each other, even in the smallest ways. From the day we were born, she made sure that we owned the exact same things, whether it was clothes, shoes, toys, or books—we even had the same color toothbrushes. Everything had to be bought in twos. Even our names had to have an equal number of letters, and that went for our middle names, too, which were exactly the same: Blossom. I was Kaylee Blossom Fitzgerald, and my sister was Haylee Blossom Fitzgerald. That was something Mother had insisted on. Daddy told us he hadn’t thought it was very significant at the time, so he’d put up little argument. I’m sure he regretted it later, as he came to regret so much he had failed to do.

Although neither of us had the courage to complain about our names, we both wished they were different. By the time we were sixteen, Haylee had gone so far as to tell people she had no middle name. When anyone looked to me for confirmation, I agreed. That was one of those little ways Haylee gradually got me to oppose things Mother had done. I was the reluctantly rebellious twin practically dragged by my hair into the fiery ring of defiance.

Actually, when I think about it, we were lucky to have two different first names. We couldn’t be Haylee One and Haylee Two or Kaylee One and Kaylee Two based on who was born first, either. Mother would never tell us who was first, and Daddy hadn’t been in the delivery room. He’d been on a business trip. I don’t know if he ever asked her which one of us was born first, but I doubt she would have told him anyway. She’d pretend not to know, or maybe she really believed we were born together, hugging and clinging to each other with our tiny pink hands and arms as we were cast out of her womb and into the world, both of us harmonizing in a cry of fear. Whenever Mother described our birth, she always said that the doctor practically had to pry us apart.

“I thought there was only one of you at first. That’s how in sync your cries were. One voice,” she would say, and she’d look starry-eyed, with that soft smile of wonder that fascinated both Haylee and me when we would sit on the floor in front of her and listen to the story of ourselves. As we grew older, she wove the magical fabric in which we would be dressed, wove it into a fantasy about the perfect twins. There was one rule that if broken would bring about disaster: we had to be loved equally, or some dragon monster would destroy our enchantment.

Daddy wasn’t anywhere nearly as obsessed about treating us equally in every way. There was never a doubt in my mind that it was something he believed Mother would grow out of as we grew older. He humored her with his smiles and nods and especially with his favorite response to what she would demand: “Whatever you say, Keri.”

He admitted that he was excited about having twins, but at first, he didn’t see any additional burdens that other parents of more than one child had. Even as very small children, we could see that he was nowhere as uptight about it, which only infuriated Mother more. During our early years, if he forgot and bought something for me and not for Haylee, or vice versa, our mother would become so upset that, in a violent rage during which I would swear I felt a whirlwind around us, she would tear up or throw out whatever he had bought. Haylee felt the whirlwind, too, and, watching Mother, we would cling to each other as tightly as we supposedly had the day we were born.

There was simply no excuse Daddy could use for what he had done that would satisfy her. For example, he couldn’t say one of us liked a certain color more or was more interested in something and he had just happened to come upon it during his travels, like someone else’s father. Oh, no. Mother would look as if she had accidentally put her finger in an electric socket and would tell him he was wrong and had done a terrible thing.

In his defense, he pleaded, “For God’s sake, Keri, this isn’t a capital offense.”

“Not a capital offense?” she fired back, her voice shrill. “How can you not see them for what they are?”

“They’re little girls,” he declared.

“No, no, no, these are not just two little girls. These are perfect twins. They see the world through the same eyes, hear it through the same ears, and smell it through the same nose.”

He shook his head, smiling but concerned. I looked at Haylee. Was Mother right? To anyone watching us, it did look as if we liked the same foods, the same flavor of ice cream, the same candy. It was true that when we were very young, anything one of us liked, the other did, too, and anything one of us hated, the other hated. Maybe we felt we were supposed to or we would lose our mystical powers. Nevertheless, Mother was shocked Daddy didn’t realize that.

“I think you’re exaggerating,” Daddy told her.

“Exaggerating? Are you in the same house, Mason? Do you see your own children?” she asked him in what, even as a young girl, I thought was a terribly condescending tone. She sounded more like she did when she chastised us.

Mother also had a habit of smacking her right fist against her right thigh when she started her responses to things that upset her this much. Sometimes, she did it so hard that both Haylee and I would flinch as if we felt the blows. After one of her more dramatic outbursts, I saw her thigh when she was getting ready to take a shower. It had a bright red circle where she had pounded it. Later it turned black-and-blue, and when Daddy mentioned it, she said, “It’s your fault, Mason. You might as well have struck me there yourself.”

Finally, Daddy always managed to stammer an excuse, but he still couldn’t ever get away with “I’ll buy the other one something tomorrow.” Whatever it was that he had bought one of us and not the other, it was gone that day, no matter what he had promised. Sometimes he would take it back and have his secretary return it to the store, but most times, after Mother had destroyed it or thrown it out, he would go back when he could and buy two this time, so he could give both of us whatever it was he thought one of us had wanted. He never looked happy about it. That satisfied Mother, though, and brought what Daddy called “a fragile armistice where we tiptoed on a floor of eggshells.” We were all smiles again. Our pounding hearts relaxed and the electric sizzle in the air disappeared, for a while anyway.

In our house, stings, burns, and aches ran around just behind the walls and just under the floors like termites. Haylee and I were in the center of continuous little tornadoes. Sometimes I thought Haylee did things deliberately so she could see these storms brew between Daddy and Mother. It was one of the differences I sensed early between us. Haylee had an impish delight in causing little explosions between our parents.

But she was far from the main cause of it all in the beginning. It wasn’t difficult to understand why this turmoil was happening around Haylee and me. In our mother’s mind, a minute after we were born, all thoughts about one of us had to be about the two of us simultaneously. She claimed it was practically blasphemous to do otherwise, because the biggest danger for any parent of identical twins was that somehow, some way, he or she would favor one over the other and destroy the confidence of the one not favored.

It was one thing to praise one of your children because he or she had done something spectacular. Everyone knew stories about fathers who favored one son over another because he was a hero on the football field or got good grades. The same was true for a daughter who might please her mother more by being more responsible, being talented in music or art, or maybe just being prettier.

But none of this could apply to identical twins, not in our mother’s way of thinking.

According to Mother, Haylee had no talents that I didn’t have, and I had none that she didn’t have. Certainly, neither of us could be prettier than the other. Our voices were so similar that people never knew which one had answered the phone. Even Daddy was confused sometimes when he called. There was always a question mark in the air first. “Haylee? Kaylee?”

When we were a little older, Haylee often pretended to be me on the phone. I think she worried that Daddy liked me more and wanted to see how he would speak if he thought I was the one answering the phone. I suspected he did like me more than he liked her, and she knew it. Once she said, “If he doesn’t know which one of us it is, he’ll say your name because he hopes it’s you.” I didn’t know if she was right. I didn’t keep as close a count as she did.

Maybe it was simply because he wasn’t around us as much as he should have been, but if I suddenly came upon him while he was reading or if Haylee did, Daddy would look at whoever it was, and his eyes would blink for a moment as his mind settled on which one of us was there. Anyone could see that he was struggling with it because Mother had him terrified about calling me Haylee or calling her Kaylee. Mother insisted that he must know which of us was which.

After all, how could our own father not know us? He agreed, and when he did get it wrong, he blamed himself for not concentrating or paying attention enough. However, he admitted that there were times when he was actually mistaken even though he was concentrating.

“They’re so alike!” he cried, hoping to be excused when Mother blew up at him for it, but all that did was prove her point and make her even more obsessive about how we were supposed to be treated.

“Of course they’re so alike. That’s always been my point. You have to try even harder, Mason, and be more careful about it,” she told him. “You never liked it when your father called you by your brother’s name, and you weren’t even twins. He is two years older than you are, but how did you feel, Mason? Go on, confess. You felt he was thinking more of him than he was of you, right?”

Daddy had admitted that to her once, so what could he do but retreat with the look of a punished puppy? I always felt sorrier for him than I did for us. Sometimes I pretended I was Haylee if he called me that, just so he would get away with it, but if Mother was there, that was impossible. She never made a mistake. I never knew why not, except to think that it was true that mothers knew their children better.

There were so many rules of behavior toward us that Mother laid down, with the power and importance of the U.S. Constitution, our own Ten Commandments:

Thou shalt not call Haylee “Kaylee,” or vice versa.

Thou shalt not buy one a gift you do not buy the other.

Thou shalt not take one somewhere and not the other.

Thou shalt not kiss one without kissing the other.

Thou shalt not hug or hold the hand of one without hugging or holding the hand of the other.

Thou shalt not say good morning or good night to one without saying it to the other.

Thou shalt not ask one a question you do not ask the other.

Thou shalt not introduce one to someone without introducing the other.

Thou shalt not tell one a story without telling it to the other.

Thou shalt not smile at one without smiling at the other.

Because of all the rules, I often thought our house was more of a laboratory than a home. I think Daddy did, too. Even Haylee admitted to feeling as if we were under observation in a glass bubble while strange new experiments on bringing up identical twins were being conducted. Many of Mother and Daddy’s friends often also seemed to believe that. I once heard someone whisper that maybe Mother was giving reports to a special government agency. I know that, like me, Haylee felt this all made us seem strange to anyone who witnessed our upbringing. There were other twins in our community, even on our street, but they were not identical, and they seemed no different from kids who had no twins. They were permitted to wear different clothes and do different things, and their mothers weren’t so uptight about potentially devastating personality complexes.

But our mother would point or nod at them and say, “Look how competitive their parents have made them. They enjoy making each other feel bad. You’ll never do that,” she would add with a confident smile. “You will always consider each other’s feelings first.” She had no idea about what was coming, crawling along on the tails of shadows toward our home and our family as we grew older.

It was difficult, if not impossible, not to feel that we really were unique, and not just because we happened to be identical twins. Haylee liked to think we did have special powers, and for a long time, I believed it, too. We looked so alike that we could pretend we were looking in a mirror when we looked at each other. In fact, we rehearsed facing each other and moving our hands to points of our faces as if we were looking into a mirror. Mother’s friends would roar with laughter, and Mother would look very proud when she had them over for a lunch during our younger years.

“They’re so perfect,” she’d whisper, her eyes fixed on us. “So perfect, down to every strand of hair.”

She would seize our right hands and turn them up so others could see our palms and then say, “Look at the lines in their hands, how exact they are in depth and length. Not all identical twins are this exact,” she’d explain.

Both of us did have some sense of difference simmering inside, though, and it grew stronger, of course, as we got older, despite Mother’s efforts to smother it. It was destined to boil over, but in Haylee before me. Mother seemed unable to imagine that. She was so confident that she was right about how we would grow up and treat each other.

I was convinced that she truly believed that Haylee and I had the same thoughts simultaneously. If one of us asked her a question, she would immediately look at the other’s face to see if the same question was on her mind. Whether it was or not, she assumed it was. Daddy never did, but she was quick to point out how we both laughed at the same things on television and looked sad at the same sad things and wondered about the same things.

“Remarkable,” she would say in a loud whisper.

She often surprised us like that, commenting on some ordinary thing we had done together and giving us the feeling that it wasn’t ordinary after all. Daddy would look at us again to see what she saw. Sometimes he would nod, but most of the time, he’d shrug and say, “It’s not unusual, Keri. Kids are kids,” and he’d go on reading or doing whatever he had been doing. More than once, I caught Mother smirking at him with great displeasure when he did that.

I often wondered why Daddy didn’t think we were as special as Mother thought we were. Did that mean he loved us less? Why wasn’t he as afraid of any differences we might show? In fact, whenever he could, especially when Mother wasn’t watching or listening, he encouraged them, and because of that, Haylee loved him more. But I never believed he loved her more than he loved me, which was what she often claimed.

It wasn’t easy for him to applaud our differences. Keeping us similar was so important to Mother that we were hardly ever alone when we were very young. It seemed she was always there hovering over us, watching carefully, eager to pounce as soon as one of us began to do something different from the other. If I reached for a cracker and she saw me do it, she would hold the box out to Haylee, too.

“I don’t want one,” Haylee would say.

“You will in a moment,” Mother would tell her, as if only she could know what either of us really wanted. It didn’t matter if Haylee wanted one just then or not. She was getting one because Mother insisted.

If Daddy was present, he would say something like “Why don’t you just let them eat when they’re hungry, Keri?”

“She’s hungry,” Mother would reply. “I know when she’s hungry, Mason. Do you cook for them? Do you know what they like and don’t like?”

He’d put up his hands like a soldier surrendering.

The same rule applied to me if Haylee reached for something or wanted something, but I saved trouble by reaching for it, too. As soon as I did, Mother would smile at me, her worried face opening like clouds parting for the sunshine.

“See?” she would say if Daddy was there.

Haylee often noticed how pleased Mother was with me and looked upset. It was as though she was keeping track of how many times our mother smiled at each of us, adding up the points we earned to prove whom Mother would eventually love more. I tried to impress her with how important it was to Mother so she wouldn’t think I was doing it to make her look bad or to make myself look better, but Haylee never believed me.

“You want her to love you more, Kaylee. Don’t say you don’t,” she told me.

Maybe I did, but I knew Mother wouldn’t let herself do that. She was too strict about how she interacted with us.

I claimed I remembered Mother changing my diaper whenever she had to change Haylee’s and her doing the same for Haylee whenever she had to change mine. Maybe it was something Daddy had told us, but the images were very vivid. It still seemed to be true as we grew out of diapers. Neither of us could wear anything fresh and clean if the other didn’t. If Haylee ripped something of hers and Mother was going to throw it out, she’d throw out mine along with it. Haylee often got her clothes and shoes dirtier than I got mine, but mine were always washed along with hers anyway.

How many times did Haylee have to eat when I was hungry, and how many times did I have to eat when she was hungry? It got so we would check with each other in little ways before crying out, reaching out, or even walking in one direction or another. If Haylee wasn’t ready to go or to do something, I didn’t, and the same was true for her. We both knew instinctively that it was the only way we could protect ourselves from doing things we didn’t want to do.

Mother didn’t realize that we were doing this deliberately or why. Instead, she would always point out our mutual requests and actions to Daddy to prove her theory that we were unusually alike.

“Don’t you see? Can’t you see how remarkable they are?” she would ask, frustrated at how calmly he took it all in. He’d shrug or just say, “Yes, remarkable,” but I could see he wasn’t as convinced about it as she was. Maybe he saw how she was often causing us to do things simultaneously, but he hesitated to question her about it, even though I could see him scrunch his face in disapproval. Sometimes he tried to be humorous about it and say something like “Hey, Keri, guess what? They only need one shadow.” He’d laugh after he had said something like that, but she never laughed at his jokes about us and soon he stopped trying.

He never really stopped complaining, though. I remember Daddy claiming that I was able to stand and walk long before Haylee could but that Mother wouldn’t let me. He said he suspected she would push me down to crawl until Haylee took her first steps. Then, and only then, would she announce our progress to him.

Once, when they were arguing about us, I overheard him tell her that he had seen her breastfeeding many times, one of us at each breast and stopping if one was satisfied, no matter how the other cried.

“It has nothing to do with hunger. You don’t know anything when it comes to that sort of thing, Mason. You’re just like any other man.”

But from the way he kept questioning her about things she had done with us, I could tell he was growing more skeptical. None of that mattered to Mother, though. She would act as if she didn’t hear what he was saying. Once he dramatically turned to the wall and complained, but she ignored him and didn’t laugh at all. For Daddy, it was like being on a boat that was sailing toward a storm in the distance but being unable to change direction.

There were just too many things Mother would do with us that annoyed him. Eventually, he complained more vigorously about things that he thought were more serious. If Haylee or I had a cold, she always gave cough medicine to both of us. Daddy objected loudly to that, but Mother assured him that whichever of us seemed fine would soon catch the same cold. “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure,” Mother declared.

Often, Haylee would begin to cough when I did, but I couldn’t help suspecting that she was just imitating me to make Mother happy and earn those love-me-more points.

“Don’t you see what a wonder they are?” Mother would say to Daddy when he didn’t react enough to please her after she had told him about something we had done together. Nothing seemed to frustrate her more.

“They’re a wonder to me no matter what,” he would say, but she would shake her head as if he was too thick to understand.

Sometimes he would try to seem more excited just to please her. Then he would reach to hug us. I saw how he always looked to Mother first so she would see that he was going to lift us both, hold us for the same amount of time, and not favor one of us over the other with his kisses and hugs. That pleased her. She would smile and nod as if he had passed some sort of test. Keeping the peace was obviously the most important thing to him, even more important than standing up for Haylee or me if either of us did something different, something original.

When I was old enough to understand him more, I realized that he wanted his home to be a true sanctuary, a place he could come to in order to escape the pressures and conflicts he had to endure in his work. Sometimes when he came home and I was there to see him first without him knowing, I would see him close his eyes and take a deep breath, as if he had finally reached fresh air. No wonder he let Mother get away with as much as she did when we were younger.

Of course, we had been too young to know what they said about us when they were alone, but later, when we were older, I understood that right from the beginning, Mother often instructed Daddy about how we were to be treated, especially how he was to talk to us, hold us, walk with us—in short, love us. Loving your children was supposed to be something that came naturally to a father or a mother. It wasn’t something that had to be taught. I knew he thought this, but he never came out and said it, at least not in our presence.

Daddy never stopped trying to get Mother to loosen up when it came to us. For our first birthday and every one thereafter, Mother made us each a cake so we would have the same number of candles and one of us wouldn’t blow out more candles than the other.

“Don’t you think you’re carrying this too far?” Daddy would ask from time to time, especially about the birthday cakes. That could set her off like a firecracker and threaten to ruin our birthday celebrations. Those hands of surrender would go up, and he would step back like someone asked to step off the stage and become simply an observer, maybe a student in a class on how to treat special twins.

In fact, when we were old enough to understand some of what she was telling him, we would also listen at the dinner table or in the living room when she was reading to Daddy from books about bringing up identical twins. She did sound like a teacher speaking to a student. It wasn’t as clear to us when we were very young that she was talking about us, of course. Sometimes, even after we realized it, it still felt as if she was talking about other children. We would sit there listening and when she paused, Daddy would look at us closely as if to confirm that we were the girls she was describing.

I shouldn’t have been surprised at how accommodating Daddy was when it came to her instructions regarding us. It wasn’t easy for anyone to challenge her. Mother was an A-plus student in high school and college. Like Daddy, she had graduated with honors. When they first met, he was majoring in business, and she was heading to law school. Daddy admitted that no one could research anything better than our mother. That’s why she would be a very good lawyer. In those early days of our upbringing, she simply overwhelmed him with facts, statistics, and psychological studies of children. She’d hand him the books or the articles she had culled and tell him to read them for himself.

“That’s all right, Keri,” he would say. “I’ll take your word for it. I’ve got plenty to read as it is.”

Even so, I caught him gazing at articles from time to time, reading the sentences Mother had underlined. She left them around the house deliberately, I thought, especially near where he sat. When I was older, I tried to read them, too, but Haylee thought they were boring. After all, they didn’t have her name in them. Mother knew Daddy was glancing at them at least and would make references to them when he started to question something she was doing. It was enough to stop him, even in mid-sentence.

However, they weren’t always arguing about us. No matter what Daddy really thought about how she was raising us, both Haylee and I were always impressed with how much Daddy respected Mother and how much she admired him, at least when we were younger. When she wasn’t angry at him for something, she treated him as if he were a movie star who just happened to be living in our house. He was a handsome, light-brown-haired, athletic six-foot-one-inch man with what Mother called “jewel-quality crystal-blue eyes, eyes that help his smile stop clocks.”

I didn’t understand what that meant, and when I didn’t understand something, Haylee certainly didn’t, either, although most of the time she would pretend she did just to make Mother happy and pile up those love-me-more points.

“How could a smile stop a clock?” I asked.

“Yes, how could his smile stop a clock?” Haylee quickly repeated. She didn’t like me being first with anything, especially questions.

“It means he is so stunning that even time itself has to pause to appreciate him,” she explained, but we both still had puzzled expressions on our faces.

Haylee looked at me, worried that this had helped me understand but not her. It hadn’t. We were too young yet, but Mother didn’t elaborate any further, except to say, “That’s why I fell in love with him. I was always very particular about boyfriends.” She laughed and kissed us and said, “Don’t worry. Someday you’ll know exactly what I’m saying. Both of you will have lightbulbs go off in your heads simultaneously.”

That was her big word for us, simultaneous.

Everything we did had to be done at the same time, and she literally meant the exact same moment. She was so positive about this and made it so important to us that we both worried that we were doing something terribly wrong if one of us did something without the other, even when she wasn’t watching us.

“I’m warm,” I might say, and indicate that I was going to take off my sweater. I could see Haylee thinking about it. Even if she wasn’t warm, too, she would nod and start to take off hers. And the same was true for me whenever she began to do something I hadn’t thought of doing. If Mother happened to see this, she would smile and kiss us as if we had done something wonderful.

“My girls,” she would say. “My perfect twins. Haylee-Kaylee, Kaylee-Haylee.”

Were we really perfect? In the beginning, Haylee liked to believe it, but gradually, as we grew older, Mother let go of “my perfect twins” and replaced it with “my perfect daughter,” which made it sound as if we were halves of the same girl.

It was reasonable to accept that every young girl would want her mother to believe that she was perfect. What Haylee never understood was that it was true for every mother except ours. Ours didn’t see one of us as perfect without the other.

How sad and troubling was the realization that substituting one word, daughter for twins, would bring about so much pain and unhappiness for Haylee and me.

And eventually, even for Mother herself.

But by then, it was far too late.

Product Details

- Publisher: Pocket Books (October 25, 2016)

- Length: 384 pages

- ISBN13: 9781476792361

Browse Related Books

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): The Mirror Sisters Mass Market Paperback 9781476792361

- Author Photo (jpg): V.C. Andrews Photograph by Thomas Van Cleave(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit