Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

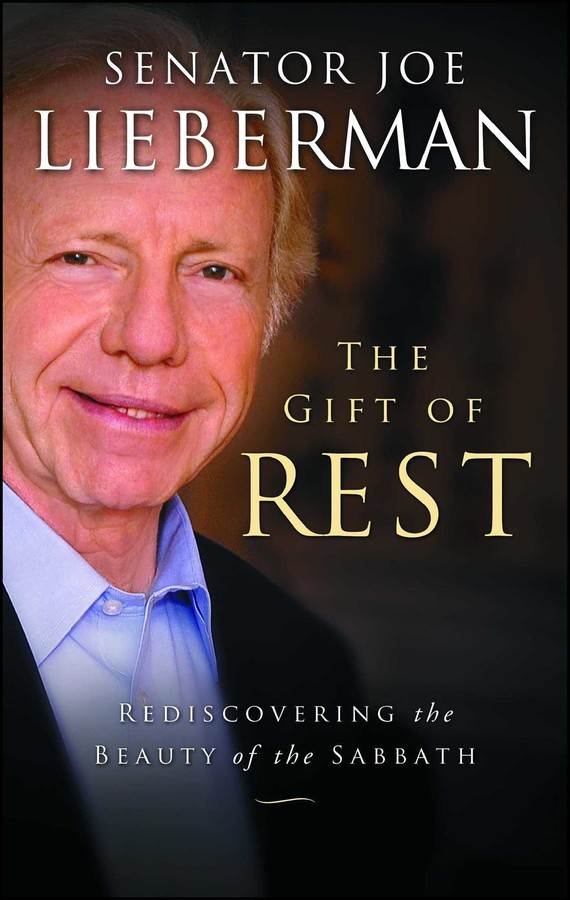

The Gift of Rest

Rediscovering the Beauty of the Sabbath

Table of Contents

About The Book

Senator Joe Lieberman shows how ceasing all activity for a weekly Sabbath observance has profound benefit—including health, relationships, and even career advancement—for people of all religions.

Our bodies and souls were created to rest—regularly—and when they do, we experience heightened productivity, improved health, and more meaningful relationships.

In these pages you’ll find wonderful stories of the senator’s spiritual journey, as well as special Sabbath experiences with political colleagues such as Bill Clinton, Al and Tipper Gore, John McCain, Colin Powell, George W. Bush, Bob Dole, and others. Senator Joe Lieberman shows how his observance of the Sabbath has not only enriched his personal and spiritual life but enhanced his career and enabled him to serve his country to his greatest capacity.

Our bodies and souls were created to rest—regularly—and when they do, we experience heightened productivity, improved health, and more meaningful relationships.

In these pages you’ll find wonderful stories of the senator’s spiritual journey, as well as special Sabbath experiences with political colleagues such as Bill Clinton, Al and Tipper Gore, John McCain, Colin Powell, George W. Bush, Bob Dole, and others. Senator Joe Lieberman shows how his observance of the Sabbath has not only enriched his personal and spiritual life but enhanced his career and enabled him to serve his country to his greatest capacity.

Excerpt

The Gift of Rest Chapter One

SABBATH EVE:

PREPARATIONS, PHYSICAL AND SPIRITUAL

Friday Afternoon

Whether I’m in Stamford or Washington, I try to get home earlier on Friday than any other day of the week so I can participate in preparing for the Sabbath. But I don’t always make it as early as I hoped. Sometimes when I walk into the kitchen, my wife, Hadassah, will be on the phone with one of our kids. “Oh, Daddy just walked through the door,” she says with a wry glance in my direction. “He said he’d be home at two-thirty. Oh, look, its four already!”

In accordance with Jewish tradition, I always bring flowers home for Hadassah and our Shabbat table on Fridays. A Capitol Hill newspaper once surveyed members of Congress, asking, among other things, “Do you ever buy your wife flowers?”

“Yes,” I said.

“How often?”

“Every week,” I answered.

“Oh my goodness,” said the reporter, “you are so romantic!” The resulting article nominated me as one of the most romantic members of Congress.

I like to think of myself as romantic, but flowers on Friday afternoon is as much a gesture of respect and love for Shabbat as it is one of respect and love for my wife. The beauty and smell of the flowers—even the ritual of stopping at the Safe-way in Georgetown or the Stop & Shop in Stamford to pick them up—is part of my preparation for the Sabbath.

Of course Hadassah is well ahead of me in getting ready. The forbidden labors of the Sabbath—thirty-nine categories, all detailed by the rabbinical authorities of long ago—are creative activities that imitate God’s creativity in the first six days. They include lighting a fire, and by extension, lighting an electric light or using a combustion engine like the one that makes your car move. Handling money is forbidden on Shabbat, and we don’t go shopping or engage in business. Cooking is prohibited, so Hadassah prepares the Sabbath meals on Thursday night and/or Friday.

The Sabbath does not just happen spontaneously at sundown on Friday. In some important ways, it begins as darkness falls on the preceding Saturday night and we prepare to return to the six days of work. We leave Shabbat, knowing it is our responsibility to be as creative and purposeful for the next six days as God was in creating the Heaven and Earth. But we also yearn to return to Shabbat to enjoy the gift of rest, just as God enjoyed the seventh day as the culmination of His creation.

By Thursday night Hadassah has decided on a plan of action for our meals. By Friday afternoon all is ready, and the wonderful smells of food fill the house. The dining room table is set with our best china, embellished by the flowers I have brought.

MEMORIES OF SHABBAT

My earliest memories of Shabbat are in my grandmother’s house—where we lived until I was eight years old. On Friday morning and afternoon, the house was busy with activity and cooking and cleaning, as if we were preparing for the arrival of a very honored guest.

In 1950, Mom and Dad, along with my sisters Rietta and Ellen and I, moved into our own house on Strawberry Hill Court in Stamford, about two miles north of my grand-mother’s. The warm, rich Sabbath memories continued there. Of all the blessings I have received in my life, the first was one of the best—maybe the best ever. I was blessed to be born the son of wonderful parents, Henry and Marcia Lieberman. They were loving, supportive, and principled. They taught my sisters and me a lot, and gave us a lot, including the gift of Sabbath rest and observance.

Mom and Dad came from very different religious backgrounds, but together they created a unified, religious home. My mother’s family was very observant. My dad’s was not. My father’s mother, Rebecca, died in New York in the influenza epidemic in 1918 when he was only three, and his father, Jacob, put him into an orphanage for Jewish boys where he stayed until he was ten. When his father remarried and moved to New Haven, he brought my father and his sister, Hannah, to live there with his new wife and her children. Dad’s family was very secular, so he received no religious education and didn’t even have a Bar Mitzvah. He graduated from high school in 1933 in the Depression, but though he was intellectually brilliant, he could not go to college. Instead he took a series of jobs that began on an overnight delivery truck for a bakery in Bridgeport and culminated in a factory in Stamford, where at a Purim dance (celebrating the story of Queen Esther) at the Stamford Jewish Center, he met Mom. When they got engaged, two members of her family who owned liquor stores offered to help Dad lease and open his own liquor store. They all agreed that as soon as he was making twenty-five dollars a week, they could get married. That incentive system worked well, and they married in 1940. It was only before their wedding—at the insistence of my mother’s family—that Dad took lessons and had his Bar Mitzvah. Although he came to Judaism later in life, his faith was deep and informed. He studied religious texts and commentaries, often in his liquor store between customers, and became quite learned. Later he joined a class in modern conversational Hebrew and became fluent. He loved the Sabbath, but as was the custom for many men at the time, he kept his liquor store open on Friday night and Saturdays because he could not afford to close. For most of my childhood, Dad would try to come home early for dinner on Friday and break for lunch on Saturday, but was otherwise not at home or synagogue on the Sabbath.

Dad was a deductive believer in God, founding his faith in God’s existence on the extraordinary sophistication and order of the natural world and on the miraculous continuity and survival of the Jewish people in the human world. Neither, he concluded, could have happened without divine support.

Dad created the intellectual basis for my religious observance, and Mom provided the spiritual depth and traditional ritual-blessed home environment to which my faith attached itself and grew. Together, they built a very spiritual home, with great pleasures and high expectations for my sisters and me. The Friday pre-Shabbat experiences that I first had in my grandmother’s house continued and grew in Mom and Dad’s house.

I would come home from school on Friday afternoon and immediately inhale the aroma of the chicken soup, meat, or kugel—a sweet baked noodle dish—or whatever else was cooking. I would go over to the stove and pick up the lid of the chicken soup pot, smell it, and then take a spoonful. Years later, when Hadassah first saw me tasting from the soup pot on Friday afternoon in my mother’s kitchen, she was appalled.

“How can you do that!” she asked in her most mannerly New England tone.

“It’s my tradition,” I answered, with a big smile as if I was Tevye in Fiddler on the Roof. But Hadassah was unconvinced.

Later I learned I had the Code of Jewish Law on my side. It may surprise you that Judaism has such things codified, but one highly authoritative legal commentary, the Mishnah Berurah, actually says, “It is meritorious to taste every dish on Erev Shabbos, so as to see that it is prepared well and properly.” Little did I realize that I had such esteemed authority to justify my undisciplined Friday afternoon ardor for chicken soup.

The Midrash, a compilation of ancient rabbinic traditions, tells the story of a Roman Emperor, named Antoninus Pius, who had a close friendship with Rabbi Judah HaNasi (the prince), the head of the Jewish community in the land of Israel at the end of the second century. Rabbi Judah served him a delicious meal when the emperor visited him on Shabbat. On another occasion, Antoninus visited on a weekday. Although the food was as elaborately prepared as before, it did not taste nearly as good. When the emperor mentioned this, Rabbi Judah replied that unfortunately each dish was missing a very special ingredient. The emperor then asked: Why did you leave out the ingredient this time? Were you skimping on costs? Rabbi Judah replied: The missing spice is the Shabbat. Food prepared and eaten in the ambience of the Sabbath has a special, delicious flavor which we cannot duplicate at a weekday meal (Genesis Rabba 11:4).

In the opening scene in Marcel Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past, the narrator tastes a cookie, a madeleine, that he associates with his childhood and that spontaneously fills him with memories and sensations. When it comes to the Sabbath, we taste or smell or see or hear, and immediately we are transported to Shabbatland—as Hadassah and I call it—with all its religious, mystical, and sensual meanings and memories. So when I walk into Hadassah’s kitchen today and smell the baking challah, the specially braided bread of Shabbat, I am instantly transported to the kitchen of another woman whose influence on me was so crucial that, without it, I might not be a Sabbath observer today.

My maternal grandmother, Minnie, or “Maintza” as she was known in Yiddish, was the religious foundation of our home. I associate her with many things, of course, but preparing for Shabbat is high on that list. We spent the first eight years of my childhood living on the second floor of her house. We called her Baba, a Yiddish word for “Grandma.” After we moved into a home of our own, Baba would spend most Sabbaths with us. She would appear at our door on Friday afternoon, Erev Shabbat, with a towel full of pastries or a pot full of some other food she had made for us. I can almost smell the pastries—the sweet, crescent-shaped rugelach—and the wonderful firm, little sugar cookies. She often brought us challah, along with delicious chicken soup.

Baba was one of the most patriotic Americans I have ever known. Like countless other immigrants to this country, she had something to compare America to—the place from which she came. There, she and her family were poor and religiously harassed. Here, she found opportunity and acceptance. One of the most miraculous experiences of her life, she once told me, was when her Christian neighbors in our ethnically diverse neighborhood would see her walking to synagogue on Saturday morning and say, “Good Sabbath, Mrs. Manger.” At those moments, Baba probably thought she was not in Connecticut, but in heaven.

Years later in 2000, on the first Sabbath after I accepted the Democratic nomination for vice president, Hadassah and I and some of our kids ended up in Lacrosse, Wisconsin. As we walked through the lovely streets from our hotel to the local synagogue on Saturday morning, people came out of their homes to wish us a good Sabbath. I thought of Baba and how right she was to be a grateful and patriotic American.

By the time of her passing away in 1967, at age eighty-six, she had moved into our house full-time. The very last words Baba spoke on the day of her death were about honoring Shabbat by preparing for it. I was in law school at Yale and clearly remember being called that Friday afternoon and told that Baba had suffered a serious stroke and that I should rush back to Stamford. On the last Erev Shabbat of Baba’s life, my mother later told me, she and Baba were in the kitchen. Baba, sitting idly at the table, said to my mother, “Masha, give me something to do l’kavod Shabbos,” which means to honor the Sabbath. My mother gave her some carrots and onions to chop for the soup. She was chopping vegetables l’kavod Shabbos when she fell ill for the last time. She died that Friday night, on Shabbos, which tradition says is a special blessing for the righteous.

At that time in my own life, I had fallen away from Sabbath observance. During my first semester as an undergraduate at Yale, I was sincerely worried that I would flunk out. I hadn’t yet realized that to get kicked out of Yale for poor grades actually required quite a determined effort. I could have easily taken time off from my school work on Shabbat, but anxiety about my academic performance, combined with peer social pressures not to be different, pulled me away in surprisingly short order, and I stopped observing the Sabbath. Ironically, I still put on tefillin, the little black leather boxes filled with sacred scrolls that observant Jewish men wear on their arms and head for morning prayer, and said my prayers each morning. Why did I do one and not the other? Maybe, I must admit, it was because putting on tefillin was private and personal, and Shabbat was more public and interrupted the weekend social flow of college life.

During college, I continued to observe the Jewish dietary laws, but by the time I reached law school, I also began straying in my eating. When I look back at this time, I am amused and a bit embarrassed by the strange distinctions I made. I would eat non-kosher chicken or beef, but never with milk because the mixing of meat and milk products is an additional prohibition in the Torah. I continued to refrain from ham, bacon, or shellfish, except on one memorable occasion. Someone convinced me to try Lobster Newburgh. After all, I reasoned, the lobster was removed from its familiar shell and cloaked in a rich sauce, therefore making it unrecognizable to both me and God. I took one mouthful of the shellfish, chewed it, swallowed it, and immediately proceeded to the men’s room where I puked up everything in my stomach. I suspect my stomach upset had more to do with theology and psychology than with gastronomy or gastroenterology.

My Baba’s death in 1967 marked the beginning of my return to Jewish observance. There was a synagogue right across the street from where I had lived for more than a year in New Haven, Connecticut but I had never gone there. The Shabbat after Baba passed away, I remember saying, “I really want to go to shul”—shul is the Yiddish term for synagogue.

Was it because of my grandmother’s last words, which so hauntingly conveyed her love of preparing for the arrival of Shabbat? Perhaps indirectly. But uppermost in my mind was the worry that Baba was my link with the Judaism of my ancestors, the Judaism of history. If I let go of the link in the chain, it would be broken and lost to me and my children after me. And so I slowly began my return to regular synagogue attendance and Sabbath and religious observance.

When I think of Erev Shabbat, I think also of Baba’s husband, my grandfather. His name was Joseph Manger. I am named for him and therefore never knew him because we Jews of European ancestry name for deceased relatives or friends. He died when my mother was just a child and he was only forty-two; his death, too, was strangely linked to Sabbath observance.

My grandfather started in the soda business in Stamford, and like many Jewish immigrants at that time he decided that supporting his family ruled out giving up that day of work on Saturday. He had been a very religiously observant man in Europe, and in 1922, he finally reached a time in America when he felt he could afford to stop working on Shabbat. It happened that year that the two-day Jewish festival of Shavuot—which like the Christian Pentecost, occurs fifty days after the beginning of Passover—began on Sunday evening. So to prepare for the festival, my grandfather went to the market on Friday and bought a live fish that the family planned to cook on Sunday and eat on Shavuot. In the meantime, over Shabbat, the fish lived in a bathtub full of water in their home. This is how things were done at that time.

On Friday night, my grandfather went to shul for prayers, excited that he was beginning the first Sabbath he would fully observe in his new country.

“I will never break Shabbos again,” he told his wife and children, including my mother, who was then seven years old.

He was so proud, so pleased. When Saturday morning came, he went to the synagogue to pray and hear the Torah read. Then he returned home for the festive lunch meal during which he complained to his wife, my Baba, of a pain in his arm. It must have been no ordinary pain because she told him he should visit the local physician, Dr. Nemoitin, at his office—which was in his home—between the afternoon and evening prayers of the Sabbath. My mother always remembered Baba and her four siblings walking her father to the corner that day as he returned to shul for the afternoon service. As he walked, he carried his infant son, my Uncle Ben. When they got to the corner, he handed my uncle to Baba, crossed the street, and smiled broadly as he and the family happily wished each other a “Good Shabbos.”

They never saw him alive again.

Following the afternoon service, on his way to the doctor’s office, he crossed the street and was struck by a bicycle and thrown onto some trolley tracks, badly hitting his head. Maybe that was the cause of his death, or maybe the pain in his arm was a symptom of an impending heart attack. In any case, he ended that Shabbat, the last of his life and the first he was ever to observe fully in America, in the hospital where he died later that night.

He had said he would never break Shabbat again and, of course, he never did. In my family, the story of Joseph Manger’s death always concludes with the ironic—and perhaps mystical—observation that on Sunday morning, after my grandfather’s life on earth ended, the fish he had purchased before Shabbat was still very much alive, swimming in the family bathtub.

So both of my mother’s parents left me with a legacy, from their lives and deaths, of preparing for the Sabbath and enjoying it.

SACRED PREPARATIONS AND DELIGHTS

Since we are forbidden to cook on the Sabbath, we need to get our food ready before the sun goes down. This practice creates a feeling of anticipation. If you were expecting an honored guest to visit your home, what would you do? You would spend hours before his or her arrival in intensive preparation. You would vacuum. You would dust. You would mop. You would cook or purchase fine food and some good wine. All would be in order well in advance of your guest’s arrival.

Even more significant are the preparations for the Sabbath, since we are preparing metaphorically and spiritually for the arrival of the most eminent guest in the world—the King of Kings. On Shabbat we feel as if we are receiving God into our homes with gratitude and love. The intensity of our experience is proportional to, among other things, the intensity of our preparation. We prepare ourselves inwardly not just by praying or meditating but also by doing physical things. In general, this is the Torah’s approach: the path to changing the inner you—your feelings and attitudes—is taking positive physical action.

There is a long tradition that speaks of this with regard to the Sabbath. The prophet Isaiah said,

If thou restrain thy foot because of the Sabbath, from pursuing thy business on My holy day; and call the Sabbath a delight, the holy day of the Lord honorable; and shalt honor it, not doing thy own ways, nor pursuing thy own business, nor speaking of vain matter, then shalt thou delight thyself in the Lord. (Isaiah 58:13–14)

The sages of old tell us that the words “delight” and “honor” refer to twin aspects of Sabbath observance. We delight in Shabbat on the day itself. But we honor it by preparing our homes and ourselves beforehand.

The physical aspect of Sabbath preparations has become increasingly important in our contemporary world where so many of us do so little physical labor. Today, jobs that leave our hands unsoiled by manual labor are increasingly common. We live in the information age, so working with information—a nonphysical entity—leaves a lot of us without the experience of real, old-fashioned labor for most of the week. Now more people work with ideas rather than with physical objects. Certainly that describes my work as a senator. Probably more than most people, I’m exempted from physical tasks. But not when it comes to preparing for the Sabbath.

When I stop at the supermarket for flowers, I often also buy a few last minute pre-Shabbat necessities or treats for the family, maybe some cookies or chocolate. When I get home, I try to help prepare the house for our Shabbat guests. I might get out my shears and trim the bushes by the side of our house or weed the garden or sweep the garage and driveway. Since we are not permitted to boil water on Shabbat, I always boil the water for instant coffee or tea, then put it in an electric urn to keep it hot over the Sabbath. I turn on the lights we want to stay on during Shabbat and turn off those we don’t, including the one in the refrigerator that we don’t want to go on each time we open the door. The Code of Jewish Law emphasizes that even if a person has household help, he should engage in manual preparations for Shabbat himself. The rabbis of the Talmud, who lived more than fifteen hundred years ago either in Israel or Babylonia, were the ultimate example of those who work with ideas rather than with their hands. But when it was time to get ready for Shabbat, they rolled up their sleeves. The Talmud lingers appreciatively over details of what these long-ago sages did to honor Shabbat. One put on a special black smock to show he was ready to get dirty. Another salted the fish. Others twined wicks for the lamps, lit the lamps, minced the beets, split the wood, lit the fire, or carried bundles into and out of his home. In a curious detail, the sage Rav Safra is said to have sought out the task of singeing the head of the animal that was to be eaten for the Shabbat meal. This was done to remove any hair or feathers. It was presumably a nasty-smelling task.

Hadassah and I try to eat in a health-conscious way, but we make small allowances for some errant but tasty consumption on Shabbat. This is in the spirit of “delighting” in the Sabbath. The Code of Jewish Law says that “depending on one’s means, he should prepare a considerable quantity of meat, wine and delicacies.”

Acquiring special foods for Shabbat is an activity that starts early in the week. In fact, the whole week is occupied, to one degree or another, with the anticipation of the Sabbath. The Sabbath day is separate and unique, but never far from our hearts and minds on the other six days.

The Jewish liturgy instructs us to say a different psalm at the end of each morning’s prayer service. It is the psalm that the Levites sang in the Temple on that day. “Today is the first day of the Sabbath week,” we begin on Sunday. “Today is the second day,” we say on Monday, and so on. We literally count the days to Shabbat, the way an eager child counts the days to a favorite holiday or to a birthday. One rabbi of old, Shammai, had the custom of seeking out some delicious food each day of the week and setting it aside for the Sabbath. This was because he interpreted the verse from the fourth commandment, “Remember the Sabbath day to keep it holy,” as meaning to do something every day of the week in preparation for Shabbat. If on a later day, he found an even tastier morsel, he would eat what he had already put aside and substitute the superior food for Shabbat. He repeated this procedure daily until he reached the Sabbath. Thus, each day of the week, he sought to eat in honor of Shabbat.

There are many other nonedible ways to “remember the Sabbath” throughout the week. One custom I have is putting reading material that is not urgent but that I definitely want to read into a specially marked folder. Shabbat is a time for rejoicing and resting but also for contemplating—reading and thinking. Reading is not one of the thirty-nine forbidden labors, but obviously if I were going over the details of a piece of legislation that I meant to propose for passage in the Senate during the next week, for example, that would take me out of the Sabbath mood. But in my “Shabbat Reading” folder I gather items of less pressing or workaday interest—articles and memos that my staff has forwarded to me or that I discover on issues I find important, intriguing, or stimulating. If there is time I also enjoy reading a good book on Shabbat. This, too, takes preparation, buying, and setting things aside for Shabbat.

If all this sounds pedestrian or even shallow, there is another side to Sabbath preparation that is intended to ready us spiritually for the special day to come. The rabbis teach that Friday afternoon, Erev Shabbat, is a time for introspection, thinking about what kind of week we have had. Did I do right by my family, friends, and co-workers? Did I do right by God? It is an important time for self-examination and even repentance. The Mishnah Berurah’s language on this is strong. Since we are about to greet the King, “it is not fitting to receive Him vested in the tattered rags of the illness of sinfulness.”

Each Friday afternoon, time allowing, I try to take a second shower of the day or—if there is enough time—a bath. I put on fresh clothes and give myself some time for spiritual preparation for the Sabbath. One of my favorite pre-Shabbat traditions is reading King Solomon’s Song of Songs, that passionate poem of love between God and the children of Israel.

But the hard truth is that there is often frenzy in the air as the clock mounts steadily toward the time when Sabbath candles are lit, shortly before sunset, signaling the start of the Sabbath. I once saw a bumper sticker on a car that read, “RELAX! THE SABBATH IS COMING.” Hah! That’s a fine sentiment for the other six days, but in reality, relaxing is the last thing there’s time to do when you are preparing for Shabbat.

Getting ready in the last couple of hours before sundown on Friday can be stressful, especially during the short days of winter, and if you have little children it can be a test of the peacefulness we all want to enjoy in our homes. Hadassah and I are past the stage of tending to our children before Shabbat—our kids are now all grown with children of their own—even so, we are not always the picture of relaxation as the Sabbath approaches.

One tradition Hadassah and I have is to phone each of our children and grandchildren wherever they happen to be on Erev Shabbat, unless of course they are with us, to wish them a good Shabbat and to give Sabbath blessings to them. Some of our grandchildren like us to sing with them the Shabbat songs they have learned in school like “Shabbat Shalom (Peaceful Sabbath), hey! Shabbat Shalom, hey!”

SUNSET BEGINNINGS

Many people have asked, “Why does the Sabbath day begin with the coming of night?” In our familiar weekday world, some view the day beginning at midnight. Others think of it as beginning at sunrise—a new day, a new sun. In Colonial times, many Americans followed the Jewish way of thinking on this. According to the historian Benson Bobrick, the Christian Sabbath was then regarded as beginning at sundown Saturday night. Some early American Christians also concluded their Sabbath as Jews customarily conclude theirs—at the appearance of three stars on Sunday evening.

So why does the Sabbath begin at sunset?

The first reason is that the Hebrew calendar is luni-solar, that is, it is a lunar calendar that is coordinated with the solar calendar, so (unlike the Muslim lunar calendar) the seasons of each holiday remain matched to the solar calendar. Passover always comes out in the spring and Rosh Hashanah—the New Year—is always in the fall. In lunar calendars the day starts with the appearance of the moon at night. But there is a deeper more spiritual reason as well: night is perceived by many as a time of trial, worry, and dread. Even King Solomon, for all his wealth and might, was troubled by nighttime. The biblical Song of Songs speaks of the terror of the night. Of Solomon’s own bed, we read, “Sixty valiant men are round about it, of the mighty men of Israel. All girt with swords and expert in war: every man has his sword upon his thigh because of the fear by night” (3:7–8). By contrast, the rising of the sun is a time of relief and rejoicing: “It is a good thing to give thanks to the Lord . . . to relate Thy steadfast love in the morning, and Thy faithfulness every night” (Psalm 92:2–3).

A beautiful insight recorded by the rabbis in the Midrash, which draws lessons from and offers additional narrative to that in the Bible, teaches that Psalm 92 was composed by the first man, Adam. According to the Midrash, Adam was created by God in the Garden of Eden, then sinned and was sentenced to be expelled from the Garden all in one day—on Friday, the sixth day of creation. When the sun went down that evening, he and Eve were filled with terror. According to this teaching, he had never seen darkness before. He assumed that the light was going out of the world because of his sin. He feared it was the end of creation, the end of the world. And it was all his fault. Imagine how terrified, how full of guilt and remorse, he was all that night.

But the sun came up the next morning! Imagine his relief, his joy. The sun for him, as for us, bore a message of hope and redemption. “Thus,” Chief Rabbi Sir Jonathan Sacks of the United Kingdom has written, “Shabbat is as close as we come to Paradise regained.” The rabbis say that Adam sang this song, Psalm 92, as a hymn to God, thanking Him for the hope God had given man that light would always follow darkness.

God gave us the Sabbath as a gift, and He meant for us to enjoy it. We begin the holy day with darkness so that we can more fully appreciate the light of the Sabbath day when it dawns.

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF SEVEN

Because the Sabbath is the seventh day, it signals to us the coming of freedom, redemption, and salvation. As my friend and teacher Rabbi Menachem Genack has pointed out to me, the Torah is full of sevens—cycles of seven days, seven weeks, and seven years. Unlike the natural movement of the sun that defines each day and the natural movement of the moon that defines each month, there is no reason in nature that a week should be seven days. Clearly, God meant something important by decreeing that the six days of labor followed by a seventh day of rest would make a week. In the Bible, seven is a code word, or symbol. It signals the state of completion or the arrival of perfection. Thus the arrival of Shabbat is meant to complete and perfect the life we have been leading all week long.

Seven weeks from the beginning of Passover, the Torah commands that we observe the festival of Shavuot, which commemorates the receiving of the Ten Commandments at Mt. Sinai. Our march to freedom was completed when we accepted the divine discipline to lead good lives. Spiritual freedom completes political and cultural freedom. Similarly, a sabbatical year was observed every seven years. A Jubilee year was celebrated at the conclusion of seven times seven years. These celebrations of seven each bring with them various forms of liberation—cessation from work, the freeing of slaves, the forgiving of debts. The verse recorded on our Liberty Bell in Philadelphia, “Proclaim liberty throughout all the land unto all the inhabitants thereof,” is from Leviticus (25:10) and describes the freeing of slaves on the occasion of the Jubilee year.

THE FREEDOM OF LAW

God offers us freedom on the Sabbath, the seventh day. It may seem paradoxical that freedom is achieved by adhering to laws, but that is another great lesson of the Bible. The liberation of the Israelites from Egyptian slavery was only the first part of God’s reentering human history. Freedom without purpose and law too often leads people to degeneracy or chaos. The Israelites and all of mankind were given their mission and destiny when Moses received the Law from God on Mt. Sinai, including the commandment to remember and guard the Sabbath. Our true freedom as human beings is dependent on our acceptance of the responsibility to serve God by obeying His laws. The laws of the Sabbath, which we will explore in detail in the following chapters, may seem burdensome at first glance, but without them, the gift of rest that comes with the Sabbath would be almost impossible to enjoy. Let me make this point personal: if there were not a divine law commanding me to rest, I would think of many good reasons to go about my normal routine on Friday night and Saturday. That is my nature. I am, for example, addicted to my BlackBerry.

Six days a week, I’m never without this little piece of plastic, chips, and wires that miraculously connects me to the rest of the world and that I hope makes me more efficient, but clearly consumes a lot of my time and attention. If there were no Sabbath law to keep me from sending and receiving email all day as I normally do, do you think I would be able to resist the temptation on the Sabbath? Not a chance. Laws have this way of setting us free. So on Friday as sunset approaches I turn off the television, the BlackBerry, the computer, and the phones as one of the final acts of preparation for Shabbat. It is all about making a separation between the six days of labor and the seventh day of rest, which in itself is a reminder of one of the Bible’s greatest lessons: God’s law constantly challenges us to make separations, to make choices, to see the difference between right and wrong, good and evil, Sabbath rest and the week of work, light and darkness.

THE SABBATH LIGHT

In our home, the Sabbath officially begins when Hadassah lights the two Sabbath candles, the last creative act until nightfall on Saturday. Why candlelight and not electric lights? Why should our last creative act of Erev Shabbat be the creation of fire? Part of the reason is that fire is the original and true light of Creation. Part is that with the entrance of the “Sabbath Queen”—the Talmud’s ancient personification of the Sabbath, in relationship to God as our cosmic King—we are welcoming an older, gentler, and timeless light, the soft, mellow candle, which replaces the modern, sharp, and artificial light of the computer, the television, and the BlackBerry screen.

Every generation has its own pharaoh and its own slave masters, uniquely based on the culture of the time. Our pharaoh may be the electronic devices—computers, televisions, iPhones—that mesmerize us, dominating hour after hour of our lives. Our eyes and faces are glued to one screen or another for much of every day. Even when we think we are at leisure, they invade our attention, holding us in their grip and separating us from our family and friends—sometimes from our faith. Too often they show us an electronic alternative reality full of negativity, trivia, or degradation. From all this, the Sabbath offers to free us for a twenty-four-hour period.

Traditionally, the Sabbath candles are lit by the woman of the home, but they can be lit by a man if no woman is present. Hadassah puts a shawl on her head and says the prescribed blessing, “Blessed are you Lord our God, King of the universe, who commanded us to light the Sabbath lamp.” As she lights the candles, she covers her eyes with her hands and thinks first about our children and grandchildren and then about our parents and loved ones who have passed away, sending out prayers for the peace of the Sabbath to them all.

And then, suddenly, the frenzy and stress end. It is Shabbat.

“Shabbat Shalom!” we greet each other and exchange Sabbath hugs and kisses. “Sabbath Peace to you.”

Welcome to Shabbatland.

Now we invite you to go with us to our synagogue for the evening service to greet the Sabbath.

SIMPLE BEGINNINGS

Get your house ready for your own version of Sabbath rest. Before the special day arrives, buy flowers or make sure that the room where you’ll enjoy your family meal is tidy and clear of clutter. If you have a dining room, eat there rather than in the kitchen.

Plan ahead. Whether dinner, lunch, or both, cook and get everything else in order for the meal. Some Christian families make preparation of Sunday lunch or dinner a family activity.

Sometimes invite extended family and friends to your Sabbath meal; other times let it be an intimate experience just for your spouse and yourself and your children. If you’re not married, make dinner for a close friend and enjoy each other’s company at home rather than going out to a restaurant.

Consider adopting a particular favorite dish or two to prepare regularly for your weekly Sabbath. The taste and smell will come to be associated with your special meal.

During the week before your Sabbath, try to do something “in honor of the Sabbath” even if—especially if—it’s still six, five, or four days away. For example, buy a food delicacy or a special bottle of wine and put them away to enjoy on the Sabbath.

Set aside some particularly enjoyable and relaxing Sabbath reading.

On the eve of your Sabbath, read from the Bible, perhaps the Song of Songs, or other evocative religious texts.

SABBATH EVE:

PREPARATIONS, PHYSICAL AND SPIRITUAL

Friday Afternoon

Whether I’m in Stamford or Washington, I try to get home earlier on Friday than any other day of the week so I can participate in preparing for the Sabbath. But I don’t always make it as early as I hoped. Sometimes when I walk into the kitchen, my wife, Hadassah, will be on the phone with one of our kids. “Oh, Daddy just walked through the door,” she says with a wry glance in my direction. “He said he’d be home at two-thirty. Oh, look, its four already!”

In accordance with Jewish tradition, I always bring flowers home for Hadassah and our Shabbat table on Fridays. A Capitol Hill newspaper once surveyed members of Congress, asking, among other things, “Do you ever buy your wife flowers?”

“Yes,” I said.

“How often?”

“Every week,” I answered.

“Oh my goodness,” said the reporter, “you are so romantic!” The resulting article nominated me as one of the most romantic members of Congress.

I like to think of myself as romantic, but flowers on Friday afternoon is as much a gesture of respect and love for Shabbat as it is one of respect and love for my wife. The beauty and smell of the flowers—even the ritual of stopping at the Safe-way in Georgetown or the Stop & Shop in Stamford to pick them up—is part of my preparation for the Sabbath.

Of course Hadassah is well ahead of me in getting ready. The forbidden labors of the Sabbath—thirty-nine categories, all detailed by the rabbinical authorities of long ago—are creative activities that imitate God’s creativity in the first six days. They include lighting a fire, and by extension, lighting an electric light or using a combustion engine like the one that makes your car move. Handling money is forbidden on Shabbat, and we don’t go shopping or engage in business. Cooking is prohibited, so Hadassah prepares the Sabbath meals on Thursday night and/or Friday.

The Sabbath does not just happen spontaneously at sundown on Friday. In some important ways, it begins as darkness falls on the preceding Saturday night and we prepare to return to the six days of work. We leave Shabbat, knowing it is our responsibility to be as creative and purposeful for the next six days as God was in creating the Heaven and Earth. But we also yearn to return to Shabbat to enjoy the gift of rest, just as God enjoyed the seventh day as the culmination of His creation.

By Thursday night Hadassah has decided on a plan of action for our meals. By Friday afternoon all is ready, and the wonderful smells of food fill the house. The dining room table is set with our best china, embellished by the flowers I have brought.

MEMORIES OF SHABBAT

My earliest memories of Shabbat are in my grandmother’s house—where we lived until I was eight years old. On Friday morning and afternoon, the house was busy with activity and cooking and cleaning, as if we were preparing for the arrival of a very honored guest.

In 1950, Mom and Dad, along with my sisters Rietta and Ellen and I, moved into our own house on Strawberry Hill Court in Stamford, about two miles north of my grand-mother’s. The warm, rich Sabbath memories continued there. Of all the blessings I have received in my life, the first was one of the best—maybe the best ever. I was blessed to be born the son of wonderful parents, Henry and Marcia Lieberman. They were loving, supportive, and principled. They taught my sisters and me a lot, and gave us a lot, including the gift of Sabbath rest and observance.

Mom and Dad came from very different religious backgrounds, but together they created a unified, religious home. My mother’s family was very observant. My dad’s was not. My father’s mother, Rebecca, died in New York in the influenza epidemic in 1918 when he was only three, and his father, Jacob, put him into an orphanage for Jewish boys where he stayed until he was ten. When his father remarried and moved to New Haven, he brought my father and his sister, Hannah, to live there with his new wife and her children. Dad’s family was very secular, so he received no religious education and didn’t even have a Bar Mitzvah. He graduated from high school in 1933 in the Depression, but though he was intellectually brilliant, he could not go to college. Instead he took a series of jobs that began on an overnight delivery truck for a bakery in Bridgeport and culminated in a factory in Stamford, where at a Purim dance (celebrating the story of Queen Esther) at the Stamford Jewish Center, he met Mom. When they got engaged, two members of her family who owned liquor stores offered to help Dad lease and open his own liquor store. They all agreed that as soon as he was making twenty-five dollars a week, they could get married. That incentive system worked well, and they married in 1940. It was only before their wedding—at the insistence of my mother’s family—that Dad took lessons and had his Bar Mitzvah. Although he came to Judaism later in life, his faith was deep and informed. He studied religious texts and commentaries, often in his liquor store between customers, and became quite learned. Later he joined a class in modern conversational Hebrew and became fluent. He loved the Sabbath, but as was the custom for many men at the time, he kept his liquor store open on Friday night and Saturdays because he could not afford to close. For most of my childhood, Dad would try to come home early for dinner on Friday and break for lunch on Saturday, but was otherwise not at home or synagogue on the Sabbath.

Dad was a deductive believer in God, founding his faith in God’s existence on the extraordinary sophistication and order of the natural world and on the miraculous continuity and survival of the Jewish people in the human world. Neither, he concluded, could have happened without divine support.

Dad created the intellectual basis for my religious observance, and Mom provided the spiritual depth and traditional ritual-blessed home environment to which my faith attached itself and grew. Together, they built a very spiritual home, with great pleasures and high expectations for my sisters and me. The Friday pre-Shabbat experiences that I first had in my grandmother’s house continued and grew in Mom and Dad’s house.

I would come home from school on Friday afternoon and immediately inhale the aroma of the chicken soup, meat, or kugel—a sweet baked noodle dish—or whatever else was cooking. I would go over to the stove and pick up the lid of the chicken soup pot, smell it, and then take a spoonful. Years later, when Hadassah first saw me tasting from the soup pot on Friday afternoon in my mother’s kitchen, she was appalled.

“How can you do that!” she asked in her most mannerly New England tone.

“It’s my tradition,” I answered, with a big smile as if I was Tevye in Fiddler on the Roof. But Hadassah was unconvinced.

Later I learned I had the Code of Jewish Law on my side. It may surprise you that Judaism has such things codified, but one highly authoritative legal commentary, the Mishnah Berurah, actually says, “It is meritorious to taste every dish on Erev Shabbos, so as to see that it is prepared well and properly.” Little did I realize that I had such esteemed authority to justify my undisciplined Friday afternoon ardor for chicken soup.

The Midrash, a compilation of ancient rabbinic traditions, tells the story of a Roman Emperor, named Antoninus Pius, who had a close friendship with Rabbi Judah HaNasi (the prince), the head of the Jewish community in the land of Israel at the end of the second century. Rabbi Judah served him a delicious meal when the emperor visited him on Shabbat. On another occasion, Antoninus visited on a weekday. Although the food was as elaborately prepared as before, it did not taste nearly as good. When the emperor mentioned this, Rabbi Judah replied that unfortunately each dish was missing a very special ingredient. The emperor then asked: Why did you leave out the ingredient this time? Were you skimping on costs? Rabbi Judah replied: The missing spice is the Shabbat. Food prepared and eaten in the ambience of the Sabbath has a special, delicious flavor which we cannot duplicate at a weekday meal (Genesis Rabba 11:4).

In the opening scene in Marcel Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past, the narrator tastes a cookie, a madeleine, that he associates with his childhood and that spontaneously fills him with memories and sensations. When it comes to the Sabbath, we taste or smell or see or hear, and immediately we are transported to Shabbatland—as Hadassah and I call it—with all its religious, mystical, and sensual meanings and memories. So when I walk into Hadassah’s kitchen today and smell the baking challah, the specially braided bread of Shabbat, I am instantly transported to the kitchen of another woman whose influence on me was so crucial that, without it, I might not be a Sabbath observer today.

My maternal grandmother, Minnie, or “Maintza” as she was known in Yiddish, was the religious foundation of our home. I associate her with many things, of course, but preparing for Shabbat is high on that list. We spent the first eight years of my childhood living on the second floor of her house. We called her Baba, a Yiddish word for “Grandma.” After we moved into a home of our own, Baba would spend most Sabbaths with us. She would appear at our door on Friday afternoon, Erev Shabbat, with a towel full of pastries or a pot full of some other food she had made for us. I can almost smell the pastries—the sweet, crescent-shaped rugelach—and the wonderful firm, little sugar cookies. She often brought us challah, along with delicious chicken soup.

Baba was one of the most patriotic Americans I have ever known. Like countless other immigrants to this country, she had something to compare America to—the place from which she came. There, she and her family were poor and religiously harassed. Here, she found opportunity and acceptance. One of the most miraculous experiences of her life, she once told me, was when her Christian neighbors in our ethnically diverse neighborhood would see her walking to synagogue on Saturday morning and say, “Good Sabbath, Mrs. Manger.” At those moments, Baba probably thought she was not in Connecticut, but in heaven.

Years later in 2000, on the first Sabbath after I accepted the Democratic nomination for vice president, Hadassah and I and some of our kids ended up in Lacrosse, Wisconsin. As we walked through the lovely streets from our hotel to the local synagogue on Saturday morning, people came out of their homes to wish us a good Sabbath. I thought of Baba and how right she was to be a grateful and patriotic American.

By the time of her passing away in 1967, at age eighty-six, she had moved into our house full-time. The very last words Baba spoke on the day of her death were about honoring Shabbat by preparing for it. I was in law school at Yale and clearly remember being called that Friday afternoon and told that Baba had suffered a serious stroke and that I should rush back to Stamford. On the last Erev Shabbat of Baba’s life, my mother later told me, she and Baba were in the kitchen. Baba, sitting idly at the table, said to my mother, “Masha, give me something to do l’kavod Shabbos,” which means to honor the Sabbath. My mother gave her some carrots and onions to chop for the soup. She was chopping vegetables l’kavod Shabbos when she fell ill for the last time. She died that Friday night, on Shabbos, which tradition says is a special blessing for the righteous.

At that time in my own life, I had fallen away from Sabbath observance. During my first semester as an undergraduate at Yale, I was sincerely worried that I would flunk out. I hadn’t yet realized that to get kicked out of Yale for poor grades actually required quite a determined effort. I could have easily taken time off from my school work on Shabbat, but anxiety about my academic performance, combined with peer social pressures not to be different, pulled me away in surprisingly short order, and I stopped observing the Sabbath. Ironically, I still put on tefillin, the little black leather boxes filled with sacred scrolls that observant Jewish men wear on their arms and head for morning prayer, and said my prayers each morning. Why did I do one and not the other? Maybe, I must admit, it was because putting on tefillin was private and personal, and Shabbat was more public and interrupted the weekend social flow of college life.

During college, I continued to observe the Jewish dietary laws, but by the time I reached law school, I also began straying in my eating. When I look back at this time, I am amused and a bit embarrassed by the strange distinctions I made. I would eat non-kosher chicken or beef, but never with milk because the mixing of meat and milk products is an additional prohibition in the Torah. I continued to refrain from ham, bacon, or shellfish, except on one memorable occasion. Someone convinced me to try Lobster Newburgh. After all, I reasoned, the lobster was removed from its familiar shell and cloaked in a rich sauce, therefore making it unrecognizable to both me and God. I took one mouthful of the shellfish, chewed it, swallowed it, and immediately proceeded to the men’s room where I puked up everything in my stomach. I suspect my stomach upset had more to do with theology and psychology than with gastronomy or gastroenterology.

My Baba’s death in 1967 marked the beginning of my return to Jewish observance. There was a synagogue right across the street from where I had lived for more than a year in New Haven, Connecticut but I had never gone there. The Shabbat after Baba passed away, I remember saying, “I really want to go to shul”—shul is the Yiddish term for synagogue.

Was it because of my grandmother’s last words, which so hauntingly conveyed her love of preparing for the arrival of Shabbat? Perhaps indirectly. But uppermost in my mind was the worry that Baba was my link with the Judaism of my ancestors, the Judaism of history. If I let go of the link in the chain, it would be broken and lost to me and my children after me. And so I slowly began my return to regular synagogue attendance and Sabbath and religious observance.

When I think of Erev Shabbat, I think also of Baba’s husband, my grandfather. His name was Joseph Manger. I am named for him and therefore never knew him because we Jews of European ancestry name for deceased relatives or friends. He died when my mother was just a child and he was only forty-two; his death, too, was strangely linked to Sabbath observance.

My grandfather started in the soda business in Stamford, and like many Jewish immigrants at that time he decided that supporting his family ruled out giving up that day of work on Saturday. He had been a very religiously observant man in Europe, and in 1922, he finally reached a time in America when he felt he could afford to stop working on Shabbat. It happened that year that the two-day Jewish festival of Shavuot—which like the Christian Pentecost, occurs fifty days after the beginning of Passover—began on Sunday evening. So to prepare for the festival, my grandfather went to the market on Friday and bought a live fish that the family planned to cook on Sunday and eat on Shavuot. In the meantime, over Shabbat, the fish lived in a bathtub full of water in their home. This is how things were done at that time.

On Friday night, my grandfather went to shul for prayers, excited that he was beginning the first Sabbath he would fully observe in his new country.

“I will never break Shabbos again,” he told his wife and children, including my mother, who was then seven years old.

He was so proud, so pleased. When Saturday morning came, he went to the synagogue to pray and hear the Torah read. Then he returned home for the festive lunch meal during which he complained to his wife, my Baba, of a pain in his arm. It must have been no ordinary pain because she told him he should visit the local physician, Dr. Nemoitin, at his office—which was in his home—between the afternoon and evening prayers of the Sabbath. My mother always remembered Baba and her four siblings walking her father to the corner that day as he returned to shul for the afternoon service. As he walked, he carried his infant son, my Uncle Ben. When they got to the corner, he handed my uncle to Baba, crossed the street, and smiled broadly as he and the family happily wished each other a “Good Shabbos.”

They never saw him alive again.

Following the afternoon service, on his way to the doctor’s office, he crossed the street and was struck by a bicycle and thrown onto some trolley tracks, badly hitting his head. Maybe that was the cause of his death, or maybe the pain in his arm was a symptom of an impending heart attack. In any case, he ended that Shabbat, the last of his life and the first he was ever to observe fully in America, in the hospital where he died later that night.

He had said he would never break Shabbat again and, of course, he never did. In my family, the story of Joseph Manger’s death always concludes with the ironic—and perhaps mystical—observation that on Sunday morning, after my grandfather’s life on earth ended, the fish he had purchased before Shabbat was still very much alive, swimming in the family bathtub.

So both of my mother’s parents left me with a legacy, from their lives and deaths, of preparing for the Sabbath and enjoying it.

SACRED PREPARATIONS AND DELIGHTS

Since we are forbidden to cook on the Sabbath, we need to get our food ready before the sun goes down. This practice creates a feeling of anticipation. If you were expecting an honored guest to visit your home, what would you do? You would spend hours before his or her arrival in intensive preparation. You would vacuum. You would dust. You would mop. You would cook or purchase fine food and some good wine. All would be in order well in advance of your guest’s arrival.

Even more significant are the preparations for the Sabbath, since we are preparing metaphorically and spiritually for the arrival of the most eminent guest in the world—the King of Kings. On Shabbat we feel as if we are receiving God into our homes with gratitude and love. The intensity of our experience is proportional to, among other things, the intensity of our preparation. We prepare ourselves inwardly not just by praying or meditating but also by doing physical things. In general, this is the Torah’s approach: the path to changing the inner you—your feelings and attitudes—is taking positive physical action.

There is a long tradition that speaks of this with regard to the Sabbath. The prophet Isaiah said,

If thou restrain thy foot because of the Sabbath, from pursuing thy business on My holy day; and call the Sabbath a delight, the holy day of the Lord honorable; and shalt honor it, not doing thy own ways, nor pursuing thy own business, nor speaking of vain matter, then shalt thou delight thyself in the Lord. (Isaiah 58:13–14)

The sages of old tell us that the words “delight” and “honor” refer to twin aspects of Sabbath observance. We delight in Shabbat on the day itself. But we honor it by preparing our homes and ourselves beforehand.

The physical aspect of Sabbath preparations has become increasingly important in our contemporary world where so many of us do so little physical labor. Today, jobs that leave our hands unsoiled by manual labor are increasingly common. We live in the information age, so working with information—a nonphysical entity—leaves a lot of us without the experience of real, old-fashioned labor for most of the week. Now more people work with ideas rather than with physical objects. Certainly that describes my work as a senator. Probably more than most people, I’m exempted from physical tasks. But not when it comes to preparing for the Sabbath.

When I stop at the supermarket for flowers, I often also buy a few last minute pre-Shabbat necessities or treats for the family, maybe some cookies or chocolate. When I get home, I try to help prepare the house for our Shabbat guests. I might get out my shears and trim the bushes by the side of our house or weed the garden or sweep the garage and driveway. Since we are not permitted to boil water on Shabbat, I always boil the water for instant coffee or tea, then put it in an electric urn to keep it hot over the Sabbath. I turn on the lights we want to stay on during Shabbat and turn off those we don’t, including the one in the refrigerator that we don’t want to go on each time we open the door. The Code of Jewish Law emphasizes that even if a person has household help, he should engage in manual preparations for Shabbat himself. The rabbis of the Talmud, who lived more than fifteen hundred years ago either in Israel or Babylonia, were the ultimate example of those who work with ideas rather than with their hands. But when it was time to get ready for Shabbat, they rolled up their sleeves. The Talmud lingers appreciatively over details of what these long-ago sages did to honor Shabbat. One put on a special black smock to show he was ready to get dirty. Another salted the fish. Others twined wicks for the lamps, lit the lamps, minced the beets, split the wood, lit the fire, or carried bundles into and out of his home. In a curious detail, the sage Rav Safra is said to have sought out the task of singeing the head of the animal that was to be eaten for the Shabbat meal. This was done to remove any hair or feathers. It was presumably a nasty-smelling task.

Hadassah and I try to eat in a health-conscious way, but we make small allowances for some errant but tasty consumption on Shabbat. This is in the spirit of “delighting” in the Sabbath. The Code of Jewish Law says that “depending on one’s means, he should prepare a considerable quantity of meat, wine and delicacies.”

Acquiring special foods for Shabbat is an activity that starts early in the week. In fact, the whole week is occupied, to one degree or another, with the anticipation of the Sabbath. The Sabbath day is separate and unique, but never far from our hearts and minds on the other six days.

The Jewish liturgy instructs us to say a different psalm at the end of each morning’s prayer service. It is the psalm that the Levites sang in the Temple on that day. “Today is the first day of the Sabbath week,” we begin on Sunday. “Today is the second day,” we say on Monday, and so on. We literally count the days to Shabbat, the way an eager child counts the days to a favorite holiday or to a birthday. One rabbi of old, Shammai, had the custom of seeking out some delicious food each day of the week and setting it aside for the Sabbath. This was because he interpreted the verse from the fourth commandment, “Remember the Sabbath day to keep it holy,” as meaning to do something every day of the week in preparation for Shabbat. If on a later day, he found an even tastier morsel, he would eat what he had already put aside and substitute the superior food for Shabbat. He repeated this procedure daily until he reached the Sabbath. Thus, each day of the week, he sought to eat in honor of Shabbat.

There are many other nonedible ways to “remember the Sabbath” throughout the week. One custom I have is putting reading material that is not urgent but that I definitely want to read into a specially marked folder. Shabbat is a time for rejoicing and resting but also for contemplating—reading and thinking. Reading is not one of the thirty-nine forbidden labors, but obviously if I were going over the details of a piece of legislation that I meant to propose for passage in the Senate during the next week, for example, that would take me out of the Sabbath mood. But in my “Shabbat Reading” folder I gather items of less pressing or workaday interest—articles and memos that my staff has forwarded to me or that I discover on issues I find important, intriguing, or stimulating. If there is time I also enjoy reading a good book on Shabbat. This, too, takes preparation, buying, and setting things aside for Shabbat.

If all this sounds pedestrian or even shallow, there is another side to Sabbath preparation that is intended to ready us spiritually for the special day to come. The rabbis teach that Friday afternoon, Erev Shabbat, is a time for introspection, thinking about what kind of week we have had. Did I do right by my family, friends, and co-workers? Did I do right by God? It is an important time for self-examination and even repentance. The Mishnah Berurah’s language on this is strong. Since we are about to greet the King, “it is not fitting to receive Him vested in the tattered rags of the illness of sinfulness.”

Each Friday afternoon, time allowing, I try to take a second shower of the day or—if there is enough time—a bath. I put on fresh clothes and give myself some time for spiritual preparation for the Sabbath. One of my favorite pre-Shabbat traditions is reading King Solomon’s Song of Songs, that passionate poem of love between God and the children of Israel.

But the hard truth is that there is often frenzy in the air as the clock mounts steadily toward the time when Sabbath candles are lit, shortly before sunset, signaling the start of the Sabbath. I once saw a bumper sticker on a car that read, “RELAX! THE SABBATH IS COMING.” Hah! That’s a fine sentiment for the other six days, but in reality, relaxing is the last thing there’s time to do when you are preparing for Shabbat.

Getting ready in the last couple of hours before sundown on Friday can be stressful, especially during the short days of winter, and if you have little children it can be a test of the peacefulness we all want to enjoy in our homes. Hadassah and I are past the stage of tending to our children before Shabbat—our kids are now all grown with children of their own—even so, we are not always the picture of relaxation as the Sabbath approaches.

One tradition Hadassah and I have is to phone each of our children and grandchildren wherever they happen to be on Erev Shabbat, unless of course they are with us, to wish them a good Shabbat and to give Sabbath blessings to them. Some of our grandchildren like us to sing with them the Shabbat songs they have learned in school like “Shabbat Shalom (Peaceful Sabbath), hey! Shabbat Shalom, hey!”

SUNSET BEGINNINGS

Many people have asked, “Why does the Sabbath day begin with the coming of night?” In our familiar weekday world, some view the day beginning at midnight. Others think of it as beginning at sunrise—a new day, a new sun. In Colonial times, many Americans followed the Jewish way of thinking on this. According to the historian Benson Bobrick, the Christian Sabbath was then regarded as beginning at sundown Saturday night. Some early American Christians also concluded their Sabbath as Jews customarily conclude theirs—at the appearance of three stars on Sunday evening.

So why does the Sabbath begin at sunset?

The first reason is that the Hebrew calendar is luni-solar, that is, it is a lunar calendar that is coordinated with the solar calendar, so (unlike the Muslim lunar calendar) the seasons of each holiday remain matched to the solar calendar. Passover always comes out in the spring and Rosh Hashanah—the New Year—is always in the fall. In lunar calendars the day starts with the appearance of the moon at night. But there is a deeper more spiritual reason as well: night is perceived by many as a time of trial, worry, and dread. Even King Solomon, for all his wealth and might, was troubled by nighttime. The biblical Song of Songs speaks of the terror of the night. Of Solomon’s own bed, we read, “Sixty valiant men are round about it, of the mighty men of Israel. All girt with swords and expert in war: every man has his sword upon his thigh because of the fear by night” (3:7–8). By contrast, the rising of the sun is a time of relief and rejoicing: “It is a good thing to give thanks to the Lord . . . to relate Thy steadfast love in the morning, and Thy faithfulness every night” (Psalm 92:2–3).

A beautiful insight recorded by the rabbis in the Midrash, which draws lessons from and offers additional narrative to that in the Bible, teaches that Psalm 92 was composed by the first man, Adam. According to the Midrash, Adam was created by God in the Garden of Eden, then sinned and was sentenced to be expelled from the Garden all in one day—on Friday, the sixth day of creation. When the sun went down that evening, he and Eve were filled with terror. According to this teaching, he had never seen darkness before. He assumed that the light was going out of the world because of his sin. He feared it was the end of creation, the end of the world. And it was all his fault. Imagine how terrified, how full of guilt and remorse, he was all that night.

But the sun came up the next morning! Imagine his relief, his joy. The sun for him, as for us, bore a message of hope and redemption. “Thus,” Chief Rabbi Sir Jonathan Sacks of the United Kingdom has written, “Shabbat is as close as we come to Paradise regained.” The rabbis say that Adam sang this song, Psalm 92, as a hymn to God, thanking Him for the hope God had given man that light would always follow darkness.

God gave us the Sabbath as a gift, and He meant for us to enjoy it. We begin the holy day with darkness so that we can more fully appreciate the light of the Sabbath day when it dawns.

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF SEVEN

Because the Sabbath is the seventh day, it signals to us the coming of freedom, redemption, and salvation. As my friend and teacher Rabbi Menachem Genack has pointed out to me, the Torah is full of sevens—cycles of seven days, seven weeks, and seven years. Unlike the natural movement of the sun that defines each day and the natural movement of the moon that defines each month, there is no reason in nature that a week should be seven days. Clearly, God meant something important by decreeing that the six days of labor followed by a seventh day of rest would make a week. In the Bible, seven is a code word, or symbol. It signals the state of completion or the arrival of perfection. Thus the arrival of Shabbat is meant to complete and perfect the life we have been leading all week long.

Seven weeks from the beginning of Passover, the Torah commands that we observe the festival of Shavuot, which commemorates the receiving of the Ten Commandments at Mt. Sinai. Our march to freedom was completed when we accepted the divine discipline to lead good lives. Spiritual freedom completes political and cultural freedom. Similarly, a sabbatical year was observed every seven years. A Jubilee year was celebrated at the conclusion of seven times seven years. These celebrations of seven each bring with them various forms of liberation—cessation from work, the freeing of slaves, the forgiving of debts. The verse recorded on our Liberty Bell in Philadelphia, “Proclaim liberty throughout all the land unto all the inhabitants thereof,” is from Leviticus (25:10) and describes the freeing of slaves on the occasion of the Jubilee year.

THE FREEDOM OF LAW

God offers us freedom on the Sabbath, the seventh day. It may seem paradoxical that freedom is achieved by adhering to laws, but that is another great lesson of the Bible. The liberation of the Israelites from Egyptian slavery was only the first part of God’s reentering human history. Freedom without purpose and law too often leads people to degeneracy or chaos. The Israelites and all of mankind were given their mission and destiny when Moses received the Law from God on Mt. Sinai, including the commandment to remember and guard the Sabbath. Our true freedom as human beings is dependent on our acceptance of the responsibility to serve God by obeying His laws. The laws of the Sabbath, which we will explore in detail in the following chapters, may seem burdensome at first glance, but without them, the gift of rest that comes with the Sabbath would be almost impossible to enjoy. Let me make this point personal: if there were not a divine law commanding me to rest, I would think of many good reasons to go about my normal routine on Friday night and Saturday. That is my nature. I am, for example, addicted to my BlackBerry.

Six days a week, I’m never without this little piece of plastic, chips, and wires that miraculously connects me to the rest of the world and that I hope makes me more efficient, but clearly consumes a lot of my time and attention. If there were no Sabbath law to keep me from sending and receiving email all day as I normally do, do you think I would be able to resist the temptation on the Sabbath? Not a chance. Laws have this way of setting us free. So on Friday as sunset approaches I turn off the television, the BlackBerry, the computer, and the phones as one of the final acts of preparation for Shabbat. It is all about making a separation between the six days of labor and the seventh day of rest, which in itself is a reminder of one of the Bible’s greatest lessons: God’s law constantly challenges us to make separations, to make choices, to see the difference between right and wrong, good and evil, Sabbath rest and the week of work, light and darkness.

THE SABBATH LIGHT

In our home, the Sabbath officially begins when Hadassah lights the two Sabbath candles, the last creative act until nightfall on Saturday. Why candlelight and not electric lights? Why should our last creative act of Erev Shabbat be the creation of fire? Part of the reason is that fire is the original and true light of Creation. Part is that with the entrance of the “Sabbath Queen”—the Talmud’s ancient personification of the Sabbath, in relationship to God as our cosmic King—we are welcoming an older, gentler, and timeless light, the soft, mellow candle, which replaces the modern, sharp, and artificial light of the computer, the television, and the BlackBerry screen.

Every generation has its own pharaoh and its own slave masters, uniquely based on the culture of the time. Our pharaoh may be the electronic devices—computers, televisions, iPhones—that mesmerize us, dominating hour after hour of our lives. Our eyes and faces are glued to one screen or another for much of every day. Even when we think we are at leisure, they invade our attention, holding us in their grip and separating us from our family and friends—sometimes from our faith. Too often they show us an electronic alternative reality full of negativity, trivia, or degradation. From all this, the Sabbath offers to free us for a twenty-four-hour period.

Traditionally, the Sabbath candles are lit by the woman of the home, but they can be lit by a man if no woman is present. Hadassah puts a shawl on her head and says the prescribed blessing, “Blessed are you Lord our God, King of the universe, who commanded us to light the Sabbath lamp.” As she lights the candles, she covers her eyes with her hands and thinks first about our children and grandchildren and then about our parents and loved ones who have passed away, sending out prayers for the peace of the Sabbath to them all.

And then, suddenly, the frenzy and stress end. It is Shabbat.

“Shabbat Shalom!” we greet each other and exchange Sabbath hugs and kisses. “Sabbath Peace to you.”

Welcome to Shabbatland.

Now we invite you to go with us to our synagogue for the evening service to greet the Sabbath.

SIMPLE BEGINNINGS

Get your house ready for your own version of Sabbath rest. Before the special day arrives, buy flowers or make sure that the room where you’ll enjoy your family meal is tidy and clear of clutter. If you have a dining room, eat there rather than in the kitchen.

Plan ahead. Whether dinner, lunch, or both, cook and get everything else in order for the meal. Some Christian families make preparation of Sunday lunch or dinner a family activity.

Sometimes invite extended family and friends to your Sabbath meal; other times let it be an intimate experience just for your spouse and yourself and your children. If you’re not married, make dinner for a close friend and enjoy each other’s company at home rather than going out to a restaurant.

Consider adopting a particular favorite dish or two to prepare regularly for your weekly Sabbath. The taste and smell will come to be associated with your special meal.

During the week before your Sabbath, try to do something “in honor of the Sabbath” even if—especially if—it’s still six, five, or four days away. For example, buy a food delicacy or a special bottle of wine and put them away to enjoy on the Sabbath.

Set aside some particularly enjoyable and relaxing Sabbath reading.

On the eve of your Sabbath, read from the Bible, perhaps the Song of Songs, or other evocative religious texts.

Product Details

- Publisher: Howard Books (August 7, 2012)

- Length: 240 pages

- ISBN13: 9781451627312

Browse Related Books

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): The Gift of Rest Trade Paperback 9781451627312

- Author Photo (jpg): Joseph I. Lieberman Photograph © Charlotte Sellmyer(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit

- Author Photo (jpg): David Klinghoffer Photograph by Diane Medved(0.8 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit