Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

Table of Contents

About The Book

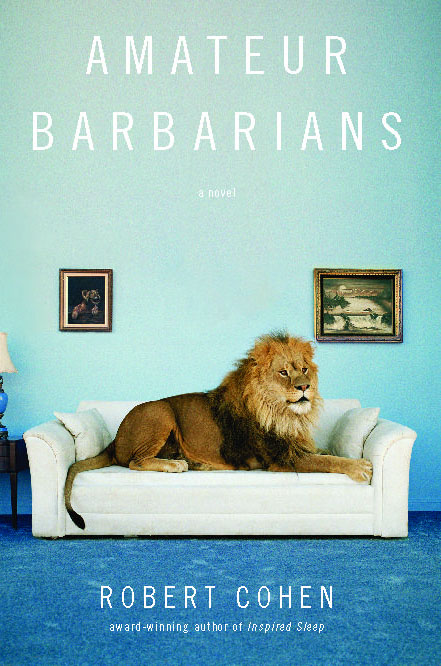

Acclaimed, award-winning novelist Robert Cohen delivers a bold, provocative exploration of the panic of midlife, following two men plateaued on either side of their forties and the unexpected consequences of changing course.

Teddy Hastings is a New England middle school principal desperate for transcendence. Unmoored by his brother’s death and a health scare of his own, he tries to broaden his ordinary life and winds up unemployed and on the wrong side of the law. Meanwhile, Oren Pierce, a perpetual grad student from New York, abandons, somewhat to his own surprise, his search for the extraordinary and begins settling into the humble existence that Teddy seeks to escape. What comforts Oren alarms Teddy, and their paths overlap as Teddy’s quest for the unknown and unfamiliar experience takes him on a rash trip to Africa, leaving Oren to assume the trappings of his life, including Teddy’s wife Gail.

Amateur Barbarians showcases a writer at the peak of his powers, tracing domestic ambivalence, the comic perils of introspection and desire, and the terror of an unlived life with Cohen’s signature wit and uncanny perception, proving yet again why he was touted by The New York Times Book Review as the “heir to Saul Bellow and Philip Roth.”

Teddy Hastings is a New England middle school principal desperate for transcendence. Unmoored by his brother’s death and a health scare of his own, he tries to broaden his ordinary life and winds up unemployed and on the wrong side of the law. Meanwhile, Oren Pierce, a perpetual grad student from New York, abandons, somewhat to his own surprise, his search for the extraordinary and begins settling into the humble existence that Teddy seeks to escape. What comforts Oren alarms Teddy, and their paths overlap as Teddy’s quest for the unknown and unfamiliar experience takes him on a rash trip to Africa, leaving Oren to assume the trappings of his life, including Teddy’s wife Gail.

Amateur Barbarians showcases a writer at the peak of his powers, tracing domestic ambivalence, the comic perils of introspection and desire, and the terror of an unlived life with Cohen’s signature wit and uncanny perception, proving yet again why he was touted by The New York Times Book Review as the “heir to Saul Bellow and Philip Roth.”

Excerpt

1

Down Time

Teddy Hastings hopped down from his treadmill after burning off the usual impressive quotas of time, mass, and distance, and reached for his bottle of purified water. If there was one thing he was good at it was running in place. Outside, the woods were dark along Montcalm Road. Sleet, like an animal scrabbling for entry, tapped against the panes.

The water he drained in one gulp. It did not appease his thirst.

To stretch out his tendons he leaned hard against the wall with both hands splayed before him, like a man holding back—or welcoming—a flood. His biceps bulged, his triceps trembled. He was a big, keg-chested man with a long list of aggrievements; even on a good day it took forever to get loose. And this was not a good day. His torso felt dense, congested; his hamstrings were knotted tight. Somewhere in the meat of his abdomen, beneath the pale, softening bulge, a cramp had clenched up like a fist. Older people, Teddy knew, were susceptible to such things, to intermittent attacks of localized pain, and though he didn’t like to think of himself as an older person, maybe now that time had come. Fortunately he didn’t mind a little pain now and then. In fact he welcomed it, as an employee welcomes a performance review, or a home team welcomes a formidable adversary: because without it nothing would be tested or advanced.

This was why he’d converted the basement that summer, after his dreary little tussle with the authorities. Why he’d taken up the hammer and power saw, plastered and sanded and paneled the walls, tacked down the carpet, plexiglassed the windows and bolstered the frames. At his age you required some insulation in your life; you couldn’t just lie down in the basement and freeze.

Above him the house lay quiet, submissive. He could feel its weight poised atop his shoulders. Yet another dumbbell to lift.

Dutifully, as if in obeisance to some cranky, intemperate god who oversaw his labors, Teddy sank to his knees and began to push himself up by the fingertips, thirty-five times. Then onto his back for thirty-five crunches. Then thirty of each, then twenty-five, then twenty, and so on, descending by increments of five toward zero’s rest. It was a simple, satisfying routine, one he’d brought home from his brief incarceration in the Carthage County lockup that summer (along with an orphaned Koran, a whopping case of shingles, and the cell phone numbers of various felons, minor miscreants, and illegal aliens) and now practiced daily on the floor like a penitent. That was how you toned the self, Teddy thought: through torment. You set goals and standards you failed to meet, and you refused to forgive yourself for failing; that was one way you knew you were alive. He imagined there must be other, less arduous ways to know you were alive, ways forgotten or as yet unrevealed. But in the absence of those he’d keep crunching.

A few weeks before, in an effort to enliven the dismal ambience of the basement, he’d taped an enormous nine-color world map, property of the Carthage Union School District, across the corrugated grid of the ceiling. Now with every sit-up he watched the map approach, fall away, then approach again, as if the world from which he’d retreated were exacting revenge, teasing him with immanence, looming into view, then fading, like a pop-up ad on a computer screen. The map itself had seen better days. Its glossy sheen was fading, its arctic circle receding; the blue line of its equator quaked and bulged. Still, it gave him pleasure just to look at the thing, to scan the hot zones, the tropical canopy, the jumbled geometries of the borders, the progression of rolling, mellifluous names. Guyana, Nigeria, Ethiopia, Malaysia. He lay on his back, crunching his way toward them like a galley slave. Somehow he never managed to arrive. His capillaries were popping, his lungs wheezed like an accordion. With two shaking fingers he took his pulse. The skin over his wrist, thick as it was, failed to muffle that monotonous riot, that thunder inside.

The windows were slick with night’s black glaze. There was no looking out. But say you looked in, Teddy thought. Say you happened by, an exile from sleep, walking your dog in the predawn gloom, and stopped to peer in through the lighted window. What would you see? A red-faced, wild-haired person heaving for breath on an all-weather carpet, holding his own hand. Fortunately Teddy Hastings was not outside. He was inside, generating steam and heat, stoking the engines. At his age a man shifts his focus, from the romance of building to the hard facts of maintaining. The building has all been done. Even if the nails are bent or mutilated and nothing is quite level or plumb or square. The building has been done; no room for more unless you tear something down. And he had no desire to tear things down. The hard thing was to keep them aloft. The tearing down came anyway; no need to contribute to that. Yet in the end one always did, it seemed.

Outside an engine was idling, some night taxi bound for the airport, waiting for a passenger to emerge from his big house on Montcalm Road. But no: it was only the high school kid who delivered the paper. Teddy listened for the dolorous thunk it made, then the tumbling fall down the steps.

Six fifteen. And so the day arrives, swollen with ads, coiled in its plastic bag.

He had nowhere to go. He was officially on leave from the middle school this year, half-pay. He had never taken a leave before, had never wanted one particularly, and now he was beginning to understand why. He wasn’t good at it. Because a man can’t live in an open field: he needs landmarks, contours, walls and roofs and floors. Once he’d stopped working, the days had become wayward and saggy, out of sync, a chain slipped free of its gears. A rift yawned open between theory and practice, between the capacity for action and its execution. There are people who prefer not to be left to their own devices, people whose own devices have grown rusty and unserviceable from lack of use, and Teddy supposed that was the lesson plan this year: he was one of these people and not the other kind. The knowledge was painful but intriguing. It gave his days the character of a search. Restless, he wandered the empty house, drifting from room to room like a detective making notes for an unsolicited investigation. In the mornings he drank his black, bitter coffee—Danielle had sent the beans all the way from Africa—listened to the radio, swept the wood floors like a charwoman even if no dirt was visible. His lunch he ate at the computer, playing solitaire, smearing the keyboard with oily fingers, splattering the screen with soup. He had never been much of a computer person before but he was becoming one now. He enjoyed solitaire but lacked the patience, and also the motive, to win. Winning ended the game, sent the kings bounding merrily away, and sealed up the window. It was losing that kept you going. It was losing that made you focus, that lured you back in with the promise of a new deal, an unplayed hand…

And so the hours passed. He could not remember feeling like this before, so indolent, so jittery, all bottled up like a soda. In the afternoons he’d sit at the old attention-starved Baldwin upright they’d bought years ago, when the girls could still be bullied into lessons, playing the same pieces at approximately the same tempo and level of competence he’d been playing since he was twelve. His Satie meandered, his Bach was a hash; his Chopin lurched and stuttered like a neurotic schoolboy. His heart it so happened was full of musical feelings; there was barely room in that clenched, spasmodic organ for the music and his feelings both. But his ear was bad, his dynamics were stiff, he lacked control and modulation, and he’d never learned to improvise. And now it was too late. He was fifty-two years old. Fifty-three. How much change was still possible? At this point he felt condemned to go on repeating the old mistakes, the unlearned lessons, forever, like a player piano scrolling methodically through its uninspired repertoire.

A jet rumbled overhead, going somewhere else. Above him the house slept on, making its night noises: its ticking clocks and groaning shutters, its whistling pipes, its four dormant stories. Sometimes, coming home late from a meeting, Teddy would marvel at the sight of it, vast and chambered, lit up in the darkness like a ship. Whether he was captain or passenger of that ship he no longer knew. More and more he felt like a stowaway.

No man becomes a prophet who was not first a shepherd.

The words were in his head when he’d awoken that morning, marooned in darkness, his body furled up like a flag. It was something he’d read in jail, a line of graffiti scratched into the wall over his cot. Jail, he’d been told, made poets of some men and criminals of others. He wondered what it had made him.

Beside him Gail stirred and sighed, her features wistful in dreams. Her body was a safe harbor just out of reach. He’d have liked to steer into it, take refuge there in her long, sleep-softened neck, the musky warmth, like risen bread, that emanated from her hair…but no: at the last moment she shifted her weight, and the mattress sank under her hip, leaving Teddy stranded alone on the far side of the bed. The cold side.

How long he’d lain there unmoving, wrapped in the straitjacket of his own arms, he didn’t know. He’d refused to look at the clock. The red glow of its digits was an annoyance. So was the rank, fitful snoring of Bruno at the foot of the bed. Soon the old dog would be sleeping for good, he thought. Wasn’t that a terrible thing? Hot mist rose in Teddy’s eyes. His nerves felt nibbled down to the cobs. His feet dangled over the edge of the bed, seeking purchase in the invisible. (Older people, he’d read, had trouble sleeping too.) The stubbled topography of the ceiling was like a tote board of his discontents. His job was no longer his job exactly. His friends were no longer his friends exactly. His wife had retreated into her own busy sphere of influence and seemed no longer quite his wife exactly. His daughters, Mimi and Danielle, had abandoned the father-ship altogether—Danny adrift in the third world; Mimi at sea in her own house, eddying listlessly in circles. He groaned. The night seemed boundless, vast, a wilderness he’d never be permitted to leave. For him, as for Bruno, life had narrowed to a waiting game. What was left to happen? Only the one great thing…

He thought of Philip, in his own hard bed underground. His brother’s death from melanoma the year before was like an explosion in space: stunning, weightless, invisible. Poor Philly, he thought, I’ll never see him again. And yet in truth he saw Philip all the time. Whenever he closed his eyes, there was Philip’s face, that pale bubble, floating untethered across the insides of his lids. Every night he loomed a little closer. Yes, it was almost oppressive at this point, almost tedious, how often he saw Philip. Time to close the door, he thought, on the whole death-of-Philip business. A year in any culture was long enough for mourning. And yet the door was such a warped, flimsy thing; it opened and opened but never closed. What kind of door was that?

It was only October but the leaves were down, the brook behind the house had grown its first skin of ice. Frost scarred the windows. Old apples, pulpy and bruised, lay strewn around the orchards like the aftermath of some stormy debauch. Gail kicked at him under the covers. No one wanted him to sleep.

Finally, as if conceding the battle to a superior force, he’d clicked on the bed lamp and reached for his book.

As a young man Teddy had no time for reading. Books were for the Philips, the moody, passive people who liked to sit alone in a room all day doing nothing. Teddy preferred the active life. No doubt Philip would have preferred the active life too, but he’d never quite mastered it, had been too haughty, too shy, too laid-back, too something. Now of course Philip was dead—really alone in a room, really doing nothing—and seeing as how he could no longer do much reading at this point, Teddy felt compelled to do it for him.

He was halfway through Thesiger’s Danakil Diary. It was his sort of book: outward-bound, exploratory. He liked material of an extreme nature. The radical solitude of the desert, the dank resistance of the jungle, the flare and assault of tropical heat. Already that year he’d sailed up the Gambia with Mungo Park, floated down the Nile with James Bruce, crossed the Horn with Richard Burton, galloped the Levant with T. E. Lawrence. Now he’d set out again, with the cool, unflappable Thesiger, through the Abyssinian lowlands and into the Danakil Depression, the harsh, primordial emptiness of Afar.

The harder the way, the more worthwhile the journey: that was the idea.

He felt, like a programmer scanning a hard drive, on the trail of an encoded truth. It had something to do with going far out of your way toward an unknown end, then coming back. Vanishing into a distant, uncharted landscape, half-mad with fatigue, navigating by dead reckoning, starving yourself down to sinew and bone, then returning from the brink of extinction to tell your tale and claim what was yours. That it had become so much easier to imagine the vanishing than the return was, Teddy supposed, a troubling sign, but then he’d never been blessed with much in the way of imagination. He put his trust in firsthand experience, trial by fire. Hence his love for the explorers—the cranks, the misfits, the egotists, the desert solitaries, the hardship freaks. He toted them home from the library in a leather rucksack he’d once intended for his own travels, for smelly, balled-up socks and filthy boxers washed out in some remote youth-hostel sink. So far all it had carried was paper: essays, lesson plans, budgetary requisitions. But that could still change.

As for the books, he piled them up on his nightstand like a miser’s currency, breathing their dusts and molds, the powders that escaped from their bindings. Their proximity was both goad and consolation. He felt their judgments bearing down on him as he slept, exonerating him from some crimes and indicting him for others. His job, he thought, was to determine which was which. It was the only job he still had.

Off in the foothills coyotes yipped and snarled, chasing prey.

Gail turned onto her side, hogging the covers, indeed the whole bed, as usual. Of course it was her bed—he’d made it for her as a wedding gift, wrestled it from the trunk of a bur oak he’d toppled with a power saw in the backyard.

“Mother of god,” Gail had groaned when he’d presented the bed, “so that’s what you’ve been up to out in the garage. And here I thought you were already tired of me.”

“I’ll show you how tired I am. Get in.”

“The wood’s still warm.” She blushed prettily in her sleeveless nightgown. They’d been married by then for two years, but so what? The wooing of Gail was an ongoing process. Her childhood had been shorn away early. Her old man’s dairy farm had slipped through his fingers; her mom, helpless, abstracted, would put daisies in Gail’s lunchbox but forget the food. Teddy’s job was to make up for their inattentions. He didn’t mind. In his own eyes he’d got lucky; he didn’t mind dealing with the infrastructural stuff—the lubing, oiling, and filtering; the ticket-buying and table-reserving; the playdate-arranging and calendar-keeping. These he made his province, while Gail staked out the unassigned territory upstairs. The inner moods, the private fears. So be it. He would deal with the externals. Doing things, fixing things. Making things.

“I hope it’s sturdier than it looks.” She flopped down onto the varnished platform, waving her limbs like a starfish; she was five foot eight but the bed seemed to swallow her. “What is it, a king or a queen?”

“What difference does it make?”

“If we want to buy a mattress and sheets, we have to know the size.”

“Let’s call it a king.”

“Really? To me it feels more like a queen.”

“Fine,” he said, “call it a queen.” But it wasn’t that either. The planks of untreated oak, left too long in the dank garage, had warped over time, thereby throwing off his measurements, altering angles that had possibly, he conceded, been drawn a bit too hastily to begin with; and so the platform had turned out to be not exactly a king and not exactly a queen, but some odd transgendered size of its own. Gail for her part wasn’t listening. Already she’d commenced the long glide toward sleep, her soft arms folded like wings, her white legs with their dark, cilialike hairs tucked in behind her rump, cushioning her fall. Teddy stood there watching over her, flushed with tenderness and pride. Okay, it wasn’t perfect, but he had built her this enormous, solid, unclassifiable thing with his own hands. And it would last. He came from strong New Hampshire stock, from hale, red-faced men with roping arteries who worked outdoors all winter in the construction trades; for all his mistakes the workmanship was sound. Even now, a quarter century later, he was impressed by how well the bed had contained them, and how long.

Still, there were nights he lay in that bed, tracing a finger over the spines of the books on the nightstand as one might a lover who has turned her back, and wonder about the cost of that containment. Where was the book with his name on the binding? Some report was expected of him, of his life on this earth; but where and how to begin, and to whom he should submit this report, and in what format and what length and what language, he didn’t know. His adulthood had thus far yielded few adventures. Marriage, children, ten years teaching math at the local middle school and another fourteen trying, as principal, to elevate it from a third-rate institution to a second-rate one. Make a book out of that! He’d never been to the Horn of Africa. Never wandered the deserts or savannas, never lunched on gazelle meat and camel piss under the acacia trees. He’d never even completed his application to the Peace Corps, though it had arrived the week he graduated college, the product of a sudden access of enthusiasm at an informational meeting in the student union. What had held him back? Why had he let that first restless storm pass, and why had it never returned? In the end it had been Philip who’d gone off after college, Philip who’d flamed out, somewhere in the jungles of Sierra Leone, of the very Peace Corps Teddy had wanted to flame into, Philip who’d then gone backpacking across Europe for two or three stoned, meandering years before finally settling, more by accident than design, into grad school in psychology at BU. Well, that was Philip’s way. The roundabout way. The passive way. The feckless way. All those incompletes, those borrowed tuitions, those pliant, tragic-looking girlfriends, those abysmal studio apartments in the Combat Zone and the far ungentrified reaches of Jamaica Plain. Meanwhile Teddy the Elder, Teddy the Constant, Teddy the Builder, had stayed put in Carthage to—do what? Attain a secondary credential in mathematics? Buy and fix up this old house? Sit on town council, umpire Little League games at the recreation park, dig up stones in the yard on weekends and compile them into walls? Spend half his life reading about things he’d never do, and the other half doing things he’d never read about? Why? He was not the dead person, lying in a hole in the dirt. He could climb out whenever he liked. He was healthy and strong and cunning as an animal. He’d made principal at thirty-nine, the second youngest in the state. He’d put money away in tech stocks at just the right time. He could go, if he chose, anywhere in the world.

He’d gone somewhere, all right. He’d gone down to the basement. He’d eased from the covers, pulled on his sweats, grabbed his running shoes in one hand and his T-shirt with the other, and slipped out the door like a thief. Gail didn’t stir. She was a long, luxurious sleeper; her face, hazy and white, floated in the dark like a lunar nimbus. Envy of her oblivion, and maybe fear of it, sent him off to the basement, through the door, down the twelve wooden steps—he knew each one’s whiny, croaking country song by heart—and around the washer and dryer to the back room, where he flicked on the wan, solitary bulb that illumined his little gym.

True, the carpet was ragged, the walls smelled of mildew, and the windows were festooned with enormous drooping cobwebs to which insect husks clung upside down, trembling from invisible drafts. He should have swept them away a long time ago. But if his time in jail had taught Teddy anything, it was that freedom comes in paradoxical forms. One man’s arbor was another man’s cage.

He stepped on the treadmill and, with the usual mixed feelings of boredom and relief, began to run. The second hand on his watch progressed in jerks. The house was quiet and tense, like the skin of a drum. Hot air swelled his temples; old fillings and tarnished crowns rattled in his jaw. He felt like a zeppelin taking leave of its moorings. The ropes that bound him were brittle and frayed; someday soon he’d snap free. No doubt this was obvious to everyone, Teddy thought, not just the people he knew and loved but other people he didn’t know, didn’t love, and who did not in all likelihood love him. People such as Judge Tierney, and Zoe Bender, and his many enemies on the school board. Together they had not so much permitted him to take a year’s leave—his existing contract was ambiguous on the subject—as insisted in the end that he take it. For the best good of all concerned. An admirable phrase, Teddy thought. He’d have liked to know how to distinguish between the best good and all the lesser kinds.

Meanwhile he kept running. It was important to make the most of it, this down time, this underground hour in his underground lair. Because it would not last forever. Soon he’d have to engineer a return. Ascend the stairs, take his place at the family table, and pretend, as all dreamers do, that he wasn’t dreaming, that sleep was wakefulness and wakefulness sleep.

But say it didn’t end, Teddy thought. Say he remained down here, amid the cobwebs and the radon, the dull, gurgling pipes. Say the family man removed himself from the family. Let the noisy model trains of domestic life sit idle, unattended. Lost the check register. Forgot how to separate the whites from the darks. Ignored the crumbly masonry poking through the plaster; the water stains spreading like rain clouds across the perforated ceiling; the recalcitrant furnace; the leaky sump pump; the asbestos sifting from the pipe joints like so much rancid flour. But then ignoring such things wasn’t his strength. No wonder he was all in knots. Gail was right: he could let nothing go.

“Look at your hands,” she’d told him that morning. “They’re all knuckles and fists like a boxer. At night you grind your teeth so loud I hear it in my sleep.”

“I’ve always ground my teeth at night. My old man did too. It’s a genetic legacy.”

“And then there’s that other thing people do at night,” she said. “I’ve almost forgotten what it’s called.”

Teddy stared at the kitchen window, awash in his own reflection. They were doing the dishes at the time. Her remark hung like steam in the air above the sink. “I thought we agreed,” he said. “A transitional period, we decided to call it.”

“Not to be a stickler or anything, but when I hear the words transitional period, I think of something that ends sooner or later.”

“That’s my point.”

“Sometimes they end badly though, Bear. That’s all I’m saying.”

He nodded. His breath was short. It was as if he were back downstairs in his little gym, loading one more weight on the bar. Truth too was an exercise, he thought.

“Look,” he said, “the cardinals are gone.”

“Don’t take it personally. They vanish around this time every year. Sunnier climes.” She sipped her tea, eyeing him over the steam, then set it in the sink and reached for her yoga bag, a flame-colored thing bedecked with dragons. “What are you doing later? Any plans?”

“None.”

She frowned, displeased but unsurprised. It was the expression she fell into every morning, it seemed, when Mimi came down, wearing the sort of thing Mimi wore. “Come with me to class,” she said. “It’ll do you good. Cleanse the mind.”

Teddy nodded and paced, hot-eyed, like a caged panther. He didn’t want to cleanse his mind. He preferred it in its natural state: messy, congested. How galling it was to be observed from a wary distance and found guilty of hunger by the very beings he looked to for nourishment. “Maybe next time,” he said.

“Suit yourself.”

He watched her bustle down the foyer and out the door, the iron knocker bouncing crazily in her wake, like the hand of an unseen visitor. But no one was there. She was always heading off these days, always leaving home early and arriving late. At dinner she’d condescend to sit for half an hour at the table with an expression of preoccupied forbearance, glancing over the mail as she picked at one of his overspiced, labor-intensive meals. Then out the door again: a meeting, a yoga class, a book group, a friend. On weekends she’d pop out of bed, wriggle into one of her sports bras, and go off biking or swimming or running along the side of the road in her orange vest. As if leisure too were an extreme sport. Her limbs had grown sleek and hard. Even their lovemaking of late, on those occasions love was still made, seemed only another workout, a cardiovascular shortcut on the long road to sleep. What was happening to them? It had something to do with time, Teddy thought, time and space: the shrinkage of one and the expansion of the other. Something to do with all these leave-takings and disappearances, with empty rooms, silent phones. If only he didn’t hate yoga so much! But the one class he’d attended had not gone well. It was held in the basement of the Unitarian church, the same dingy, blue-carpeted space to which he used to drag his daughters to Sunday school against their wills. Now he too submitted to the larger, impersonal force. Women in leotards were poised on their mats, practicing their breathing. Teddy tried his best to attain the positions, the trembling Triangle, the ungainly Warrior, the flaccid Bow from which no arrow would ever be launched, and then those postures that came naturally it seemed to animals alone—the Lion, the Cobra, the Camel, the Upward Facing Dog, the Downward Facing Dog. But he could not hold still. He was left feeling very downward and doglike indeed, and hardly inclined to attend another yoga class should Gail ever happen to invite him again, which now of course she never would.

Earlier that week they’d gone out for his birthday to the Carthage Inn, the place one went for these things. Helplessly Teddy had looked over the menu. It was the same as last time. Nonetheless he’d managed over the course of the evening to consume a salad, a cup of gluey bisque, two sesame rolls, a humongous, fat-marbled shank of lamb, the mashed potatoes and asparagus it came with, and about nine-tenths of the crème brûlée he and Gail had agreed to split in half. His lone act of restraint came at the end, with the pale, bluish nonfat milk he poured stingily into his coffee like a rhetorical gesture. The rest he’d devoured like an animal—sopping up the juices, sucking greedily on the shank bone, furrowing out the marrow with his tongue—while Gail grazed numbly at the top leaves of her spinach salad, then consigned the rest to sleep moldering in the Dumpster. What waste. Maybe if they lived in the city there would be more to do at night and less need to indulge in these enormous, sedentary dinners that dulled the senses. But Gail’s law practice was here in Carthage, and she was happy here, or if not happy then at least more or less content with her present level of not-happiness, as opposed to the potential not-happiness of moving somewhere else, which he did not think they ever would. They’d talked about moving for years but had in fact gone nowhere. Arguably the talk itself had become a form of movement, Teddy thought, or else a substitute for it, providing just enough current to keep the raft of the possible afloat. It was hard to know.

And now it was too late. He was fifty-two. Fifty-three. The raft had become rickety, precarious; they’d flirted with the possible too long; their credibility was gone. At some point you have to stop thinking about moving, Teddy thought, sliding his gold card out of his wallet, and just live where you are. You ate your meal and drank your wine and tried to wring some enjoyment out of it before the bill came.

“Shoot,” Gail said on their way to the car, “I meant to put it on my card.”

“It’s a joint account. What difference does it make?”

“It makes a difference to me. I wanted to be the one taking you out for a change.”

“It doesn’t matter,” he said.

But in fact it did seem to matter, on some level, and his insistence that it didn’t made it matter more, not less. And now, down in the basement, running on his treadmill, he regretted his half of that conversation, and his half of the meal too, which had been more like four-fifths. The lamb was still with him. He could feel it, the carbs and proteins, the sugars and fats, settling sluggishly, like ocean sediment, in the linings of his heart. He’d be working it off for days. Both of his daughters were vegetarians; he was beginning to understand why.

He decided to keep running for another few miles and then see how he felt. The phrase came to him often these days: see how he felt. Right now as it happened he felt more or less okay, but he would take care of that.

He programmed the treadmill to its maximum verticality, so that for all intents and purposes he was running straight uphill, climbing a slope he couldn’t see toward a summit he couldn’t reach. His heart, that petulant child, pounded sullenly at his eardrums. The lungs in his chest rattled like toys. This inner hullabaloo, though alarming, was also the source of a tenuous satisfaction. He had after all bought this machine of his own free will, submitted himself voluntarily to its tedious and complicated punishments. And for what? Good health. The two words were conjoined in his mind like an arranged marriage—sturdy, dutiful, surprisingly effective. Good health, Teddy knew, was an absolute good. Not many things were. He knew this because he’d recently been forced to confront its evil twin, bad health—an incredibly clarifying experience he was eager not to repeat.

Well, he thought, get used to it. From here on life was a numbers game, an actuarial box score. Weight, body fat, heart rate, cholesterol, PSA. Fortunately he had a gift for numbers. But of course there were limits to what the numbers could tell you. Look at Philip: his numbers had been okay too. So had Don Blackburn’s, and look at him: a stroke like a bolt from the blue.

Of course in Don’s case factors of nature and nurture had to be considered. The man was fifty pounds overweight and did not own so much as a pair of sneakers. Clearly he’d made few of the compromises with age that Teddy himself had made. Don was still a smoker, a drinker, a gorger, a glutton. On bad days he’d blow through his classroom like a nor’easter, bushy-browed, all hot wind and pendulous rumbling, clogging up the aisles with his great mounded belly, his arms tossing around like tree limbs, squalls of saliva issuing from the corners of his mouth. That was what happened to English teachers. They grew indulgent as they aged, arch and capricious and mean. Don had long since lost interest in his lesson plans. He’d stand at the board making jokes the kids didn’t understand, improvising fey little couplets of dactylic verse—

Silly Miss Peters has forgotten her binder

If only Miss Cobden had thought to remind her.

He might have been auditioning for one of those fat, burdened fools—Falstaff, Lear, Willy Loman—he was always requisitioning buses and handing out permission slips to take his students to see. Don too was a mess. His face a checkerboard of distress, at once pallid and overripe; his eyes like dry wells sunk deep in his cheeks. He had never seemed all that healthy in the best of times, and it had not been the best of times for Don Blackburn, not in a long while. Now he was into the other times, the worst of times. Now you could feel the furnace of his loneliness roaring in his belly, steaming up the storm windows, pouring through the vents.

Think in terms of forgiving me everything, Don would say in his cups. God knows I do.

And Teddy had. Selflessly and tolerantly he’d endured Don’s eruptions over the years—the drunken phone calls, the retributive rants, the mawkish apologies—not because selfless, tolerant endurance of other people’s moods was one of Teddy’s specialties, though it was; not because he and Don were vaguely related by marriage, though they were; not because they’d successfully worked together at the middle school for twenty years now, though they had; or because, like most people, Teddy found both instruction and entertainment in other people’s tragedies, though he did—no, he endured them because he genuinely liked Don, and feared him, and pitied him, and felt vaguely protective of him, and, though he did not like to dwell on this, vaguely guilty toward him as well. Three years before, after a successful production of Guys and Dolls, he’d walked petite, unsmiling Vera Blackburn out to her car and wound up kissing her smack on the mouth. Right there in the parking lot, under the fizzy halo of the sodium lights! Christ alone knew why; he’d only intended to buss her on the cheek. But Vera was so short, and Teddy was so tall, and his big, lumbering weight kept moving downward as if of its own volition, the white lines of the parking grid blurring at his feet, and suddenly Vera’s fine dark hair was slipping its braid, her split ends whisking like feathers against his cheek, and it was as if they’d begun to sleepwalk their way through some strange, weightless twilight where everything was permissible and nothing quite mattered. Or was it vice versa? Of course the kiss itself lasted only a moment. And if later Teddy came to regret that kiss for ethical reasons almost as much as he’d enjoyed it at the time for aesthetic ones, on balance he was grateful for it, for the wealth of that deposit in his memory, and for the warm, tangeriney taste of Vera’s lips, which remained with him as he sailed home that night in his purring Accord. All the lights were with him. Signs bowed in the wind; mica chips glittered in the sidewalks; the shops and their awnings fell away behind him, folding up like stage flats. As if this social world with its painted signs were only another amateurish set, waiting to be struck. When he got home that night he drank a little bourbon and let Bruno out to do his business, to approach and avoid the invisible fence that ringed the yard; and then he turned off the porch light, put his glass in the sink, and went upstairs to have his way with his own lawful sleeping wife. And that was that. Not long after, Vera Blackburn moved to San Francisco and opened a maternity boutique, ripping a small tear in the social fabric through which the weather poured in on them all.

It was the sort of bad luck Don was famous for. People said you made your own luck and Teddy supposed that was true up to a point—it was why he ran on the treadmill like this every morning—but the point was not as flexible as it used to be. Nothing was, it seemed, when you were fifty-two. Fifty-three.

His heart thudded against his ribs. His right knee was showing signs of meniscus fatigue. He felt a surge in the current, a kind of electrical empathy, as if he and the treadmill were old running partners huffing their way home, and not a man alone in an insulated basement with $700 worth of sporting equipment. He gripped the handles hard, holding on. Goddamnit, here was a position he could hold: not stillness, but motion; not tranquillity, but noisy, pounding labor. Blind persistence. Putting one foot in front of the other, again and again, while the rubberized mat unfurled beneath him like the flattest, most unvarying of rivers. This he could do. Never mind his recent trials, both medical and legal. Never mind the school board. Never mind that Gail had failed to present him with a birthday present at dinner, and that there was no present from his daughters either, or for that matter no card. So what? He was a grown man, not a greedy and dependent child, mooning after the attention of his loved ones, but a vigorous, determined adult of fifty-two. Fifty-three…

Finally he’d had enough and flicked off the machine. His towel smelled salty and rank; his shirt clung to his ribs like a second skin. He left it there, rolled up on his chest, like an animal skin half-molted. Water rushed through the pipes overhead. Mimi taking her shower. By the time she was finished the hot water would be depleted, the mirror lost in steam, the bar of Lifebuoy slim as a wafer. What an uphill battle it was, getting yourself clean.

Now he heard Gail’s footsteps in the kitchen. The dull whine of the coffee grinder, the ticking of Bruno’s paws across the floor. Mimi would be down in a few minutes, wet-haired and irritable, unhappy with her clothes. Gail, looking up from one or another domestic task she seemed increasingly ambivalent about performing, would make a motherly, affectionate joke—or a not-so-motherly, not-so-affectionate joke—after which with astonishing but not unprecedented suddenness Mimi would wind up in tears. There would be slammed drawers, and operatic threats and complaints, and inevitably a portion of breakfast would succumb to gravity and find its way to the floor, where bony old Bruno would trot over to lick it up. That was how it would go. The dog’s presence at their feet, his goofy and enduring goodness, would allow for a truce. Then the room would grow still. Then after a while the stillness itself would become a problem, as stillness does. Dad’s absence would be remarked upon by both parties, if not resented, if not singled out for blame for pretty much everything that was wrong. Such were the statistical probabilities of the morning. The coffee, the newspaper, the fruit shakes, the fights, the dog, the blame, the toast. The rituals of a household patiently assembling itself. Making its own luck.

Ten more sit-ups, Teddy thought. Because of the lamb.

Copyright © 2009 by Robert Cohen

Down Time

Teddy Hastings hopped down from his treadmill after burning off the usual impressive quotas of time, mass, and distance, and reached for his bottle of purified water. If there was one thing he was good at it was running in place. Outside, the woods were dark along Montcalm Road. Sleet, like an animal scrabbling for entry, tapped against the panes.

The water he drained in one gulp. It did not appease his thirst.

To stretch out his tendons he leaned hard against the wall with both hands splayed before him, like a man holding back—or welcoming—a flood. His biceps bulged, his triceps trembled. He was a big, keg-chested man with a long list of aggrievements; even on a good day it took forever to get loose. And this was not a good day. His torso felt dense, congested; his hamstrings were knotted tight. Somewhere in the meat of his abdomen, beneath the pale, softening bulge, a cramp had clenched up like a fist. Older people, Teddy knew, were susceptible to such things, to intermittent attacks of localized pain, and though he didn’t like to think of himself as an older person, maybe now that time had come. Fortunately he didn’t mind a little pain now and then. In fact he welcomed it, as an employee welcomes a performance review, or a home team welcomes a formidable adversary: because without it nothing would be tested or advanced.

This was why he’d converted the basement that summer, after his dreary little tussle with the authorities. Why he’d taken up the hammer and power saw, plastered and sanded and paneled the walls, tacked down the carpet, plexiglassed the windows and bolstered the frames. At his age you required some insulation in your life; you couldn’t just lie down in the basement and freeze.

Above him the house lay quiet, submissive. He could feel its weight poised atop his shoulders. Yet another dumbbell to lift.

Dutifully, as if in obeisance to some cranky, intemperate god who oversaw his labors, Teddy sank to his knees and began to push himself up by the fingertips, thirty-five times. Then onto his back for thirty-five crunches. Then thirty of each, then twenty-five, then twenty, and so on, descending by increments of five toward zero’s rest. It was a simple, satisfying routine, one he’d brought home from his brief incarceration in the Carthage County lockup that summer (along with an orphaned Koran, a whopping case of shingles, and the cell phone numbers of various felons, minor miscreants, and illegal aliens) and now practiced daily on the floor like a penitent. That was how you toned the self, Teddy thought: through torment. You set goals and standards you failed to meet, and you refused to forgive yourself for failing; that was one way you knew you were alive. He imagined there must be other, less arduous ways to know you were alive, ways forgotten or as yet unrevealed. But in the absence of those he’d keep crunching.

A few weeks before, in an effort to enliven the dismal ambience of the basement, he’d taped an enormous nine-color world map, property of the Carthage Union School District, across the corrugated grid of the ceiling. Now with every sit-up he watched the map approach, fall away, then approach again, as if the world from which he’d retreated were exacting revenge, teasing him with immanence, looming into view, then fading, like a pop-up ad on a computer screen. The map itself had seen better days. Its glossy sheen was fading, its arctic circle receding; the blue line of its equator quaked and bulged. Still, it gave him pleasure just to look at the thing, to scan the hot zones, the tropical canopy, the jumbled geometries of the borders, the progression of rolling, mellifluous names. Guyana, Nigeria, Ethiopia, Malaysia. He lay on his back, crunching his way toward them like a galley slave. Somehow he never managed to arrive. His capillaries were popping, his lungs wheezed like an accordion. With two shaking fingers he took his pulse. The skin over his wrist, thick as it was, failed to muffle that monotonous riot, that thunder inside.

The windows were slick with night’s black glaze. There was no looking out. But say you looked in, Teddy thought. Say you happened by, an exile from sleep, walking your dog in the predawn gloom, and stopped to peer in through the lighted window. What would you see? A red-faced, wild-haired person heaving for breath on an all-weather carpet, holding his own hand. Fortunately Teddy Hastings was not outside. He was inside, generating steam and heat, stoking the engines. At his age a man shifts his focus, from the romance of building to the hard facts of maintaining. The building has all been done. Even if the nails are bent or mutilated and nothing is quite level or plumb or square. The building has been done; no room for more unless you tear something down. And he had no desire to tear things down. The hard thing was to keep them aloft. The tearing down came anyway; no need to contribute to that. Yet in the end one always did, it seemed.

Outside an engine was idling, some night taxi bound for the airport, waiting for a passenger to emerge from his big house on Montcalm Road. But no: it was only the high school kid who delivered the paper. Teddy listened for the dolorous thunk it made, then the tumbling fall down the steps.

Six fifteen. And so the day arrives, swollen with ads, coiled in its plastic bag.

He had nowhere to go. He was officially on leave from the middle school this year, half-pay. He had never taken a leave before, had never wanted one particularly, and now he was beginning to understand why. He wasn’t good at it. Because a man can’t live in an open field: he needs landmarks, contours, walls and roofs and floors. Once he’d stopped working, the days had become wayward and saggy, out of sync, a chain slipped free of its gears. A rift yawned open between theory and practice, between the capacity for action and its execution. There are people who prefer not to be left to their own devices, people whose own devices have grown rusty and unserviceable from lack of use, and Teddy supposed that was the lesson plan this year: he was one of these people and not the other kind. The knowledge was painful but intriguing. It gave his days the character of a search. Restless, he wandered the empty house, drifting from room to room like a detective making notes for an unsolicited investigation. In the mornings he drank his black, bitter coffee—Danielle had sent the beans all the way from Africa—listened to the radio, swept the wood floors like a charwoman even if no dirt was visible. His lunch he ate at the computer, playing solitaire, smearing the keyboard with oily fingers, splattering the screen with soup. He had never been much of a computer person before but he was becoming one now. He enjoyed solitaire but lacked the patience, and also the motive, to win. Winning ended the game, sent the kings bounding merrily away, and sealed up the window. It was losing that kept you going. It was losing that made you focus, that lured you back in with the promise of a new deal, an unplayed hand…

And so the hours passed. He could not remember feeling like this before, so indolent, so jittery, all bottled up like a soda. In the afternoons he’d sit at the old attention-starved Baldwin upright they’d bought years ago, when the girls could still be bullied into lessons, playing the same pieces at approximately the same tempo and level of competence he’d been playing since he was twelve. His Satie meandered, his Bach was a hash; his Chopin lurched and stuttered like a neurotic schoolboy. His heart it so happened was full of musical feelings; there was barely room in that clenched, spasmodic organ for the music and his feelings both. But his ear was bad, his dynamics were stiff, he lacked control and modulation, and he’d never learned to improvise. And now it was too late. He was fifty-two years old. Fifty-three. How much change was still possible? At this point he felt condemned to go on repeating the old mistakes, the unlearned lessons, forever, like a player piano scrolling methodically through its uninspired repertoire.

A jet rumbled overhead, going somewhere else. Above him the house slept on, making its night noises: its ticking clocks and groaning shutters, its whistling pipes, its four dormant stories. Sometimes, coming home late from a meeting, Teddy would marvel at the sight of it, vast and chambered, lit up in the darkness like a ship. Whether he was captain or passenger of that ship he no longer knew. More and more he felt like a stowaway.

No man becomes a prophet who was not first a shepherd.

The words were in his head when he’d awoken that morning, marooned in darkness, his body furled up like a flag. It was something he’d read in jail, a line of graffiti scratched into the wall over his cot. Jail, he’d been told, made poets of some men and criminals of others. He wondered what it had made him.

Beside him Gail stirred and sighed, her features wistful in dreams. Her body was a safe harbor just out of reach. He’d have liked to steer into it, take refuge there in her long, sleep-softened neck, the musky warmth, like risen bread, that emanated from her hair…but no: at the last moment she shifted her weight, and the mattress sank under her hip, leaving Teddy stranded alone on the far side of the bed. The cold side.

How long he’d lain there unmoving, wrapped in the straitjacket of his own arms, he didn’t know. He’d refused to look at the clock. The red glow of its digits was an annoyance. So was the rank, fitful snoring of Bruno at the foot of the bed. Soon the old dog would be sleeping for good, he thought. Wasn’t that a terrible thing? Hot mist rose in Teddy’s eyes. His nerves felt nibbled down to the cobs. His feet dangled over the edge of the bed, seeking purchase in the invisible. (Older people, he’d read, had trouble sleeping too.) The stubbled topography of the ceiling was like a tote board of his discontents. His job was no longer his job exactly. His friends were no longer his friends exactly. His wife had retreated into her own busy sphere of influence and seemed no longer quite his wife exactly. His daughters, Mimi and Danielle, had abandoned the father-ship altogether—Danny adrift in the third world; Mimi at sea in her own house, eddying listlessly in circles. He groaned. The night seemed boundless, vast, a wilderness he’d never be permitted to leave. For him, as for Bruno, life had narrowed to a waiting game. What was left to happen? Only the one great thing…

He thought of Philip, in his own hard bed underground. His brother’s death from melanoma the year before was like an explosion in space: stunning, weightless, invisible. Poor Philly, he thought, I’ll never see him again. And yet in truth he saw Philip all the time. Whenever he closed his eyes, there was Philip’s face, that pale bubble, floating untethered across the insides of his lids. Every night he loomed a little closer. Yes, it was almost oppressive at this point, almost tedious, how often he saw Philip. Time to close the door, he thought, on the whole death-of-Philip business. A year in any culture was long enough for mourning. And yet the door was such a warped, flimsy thing; it opened and opened but never closed. What kind of door was that?

It was only October but the leaves were down, the brook behind the house had grown its first skin of ice. Frost scarred the windows. Old apples, pulpy and bruised, lay strewn around the orchards like the aftermath of some stormy debauch. Gail kicked at him under the covers. No one wanted him to sleep.

Finally, as if conceding the battle to a superior force, he’d clicked on the bed lamp and reached for his book.

As a young man Teddy had no time for reading. Books were for the Philips, the moody, passive people who liked to sit alone in a room all day doing nothing. Teddy preferred the active life. No doubt Philip would have preferred the active life too, but he’d never quite mastered it, had been too haughty, too shy, too laid-back, too something. Now of course Philip was dead—really alone in a room, really doing nothing—and seeing as how he could no longer do much reading at this point, Teddy felt compelled to do it for him.

He was halfway through Thesiger’s Danakil Diary. It was his sort of book: outward-bound, exploratory. He liked material of an extreme nature. The radical solitude of the desert, the dank resistance of the jungle, the flare and assault of tropical heat. Already that year he’d sailed up the Gambia with Mungo Park, floated down the Nile with James Bruce, crossed the Horn with Richard Burton, galloped the Levant with T. E. Lawrence. Now he’d set out again, with the cool, unflappable Thesiger, through the Abyssinian lowlands and into the Danakil Depression, the harsh, primordial emptiness of Afar.

The harder the way, the more worthwhile the journey: that was the idea.

He felt, like a programmer scanning a hard drive, on the trail of an encoded truth. It had something to do with going far out of your way toward an unknown end, then coming back. Vanishing into a distant, uncharted landscape, half-mad with fatigue, navigating by dead reckoning, starving yourself down to sinew and bone, then returning from the brink of extinction to tell your tale and claim what was yours. That it had become so much easier to imagine the vanishing than the return was, Teddy supposed, a troubling sign, but then he’d never been blessed with much in the way of imagination. He put his trust in firsthand experience, trial by fire. Hence his love for the explorers—the cranks, the misfits, the egotists, the desert solitaries, the hardship freaks. He toted them home from the library in a leather rucksack he’d once intended for his own travels, for smelly, balled-up socks and filthy boxers washed out in some remote youth-hostel sink. So far all it had carried was paper: essays, lesson plans, budgetary requisitions. But that could still change.

As for the books, he piled them up on his nightstand like a miser’s currency, breathing their dusts and molds, the powders that escaped from their bindings. Their proximity was both goad and consolation. He felt their judgments bearing down on him as he slept, exonerating him from some crimes and indicting him for others. His job, he thought, was to determine which was which. It was the only job he still had.

Off in the foothills coyotes yipped and snarled, chasing prey.

Gail turned onto her side, hogging the covers, indeed the whole bed, as usual. Of course it was her bed—he’d made it for her as a wedding gift, wrestled it from the trunk of a bur oak he’d toppled with a power saw in the backyard.

“Mother of god,” Gail had groaned when he’d presented the bed, “so that’s what you’ve been up to out in the garage. And here I thought you were already tired of me.”

“I’ll show you how tired I am. Get in.”

“The wood’s still warm.” She blushed prettily in her sleeveless nightgown. They’d been married by then for two years, but so what? The wooing of Gail was an ongoing process. Her childhood had been shorn away early. Her old man’s dairy farm had slipped through his fingers; her mom, helpless, abstracted, would put daisies in Gail’s lunchbox but forget the food. Teddy’s job was to make up for their inattentions. He didn’t mind. In his own eyes he’d got lucky; he didn’t mind dealing with the infrastructural stuff—the lubing, oiling, and filtering; the ticket-buying and table-reserving; the playdate-arranging and calendar-keeping. These he made his province, while Gail staked out the unassigned territory upstairs. The inner moods, the private fears. So be it. He would deal with the externals. Doing things, fixing things. Making things.

“I hope it’s sturdier than it looks.” She flopped down onto the varnished platform, waving her limbs like a starfish; she was five foot eight but the bed seemed to swallow her. “What is it, a king or a queen?”

“What difference does it make?”

“If we want to buy a mattress and sheets, we have to know the size.”

“Let’s call it a king.”

“Really? To me it feels more like a queen.”

“Fine,” he said, “call it a queen.” But it wasn’t that either. The planks of untreated oak, left too long in the dank garage, had warped over time, thereby throwing off his measurements, altering angles that had possibly, he conceded, been drawn a bit too hastily to begin with; and so the platform had turned out to be not exactly a king and not exactly a queen, but some odd transgendered size of its own. Gail for her part wasn’t listening. Already she’d commenced the long glide toward sleep, her soft arms folded like wings, her white legs with their dark, cilialike hairs tucked in behind her rump, cushioning her fall. Teddy stood there watching over her, flushed with tenderness and pride. Okay, it wasn’t perfect, but he had built her this enormous, solid, unclassifiable thing with his own hands. And it would last. He came from strong New Hampshire stock, from hale, red-faced men with roping arteries who worked outdoors all winter in the construction trades; for all his mistakes the workmanship was sound. Even now, a quarter century later, he was impressed by how well the bed had contained them, and how long.

Still, there were nights he lay in that bed, tracing a finger over the spines of the books on the nightstand as one might a lover who has turned her back, and wonder about the cost of that containment. Where was the book with his name on the binding? Some report was expected of him, of his life on this earth; but where and how to begin, and to whom he should submit this report, and in what format and what length and what language, he didn’t know. His adulthood had thus far yielded few adventures. Marriage, children, ten years teaching math at the local middle school and another fourteen trying, as principal, to elevate it from a third-rate institution to a second-rate one. Make a book out of that! He’d never been to the Horn of Africa. Never wandered the deserts or savannas, never lunched on gazelle meat and camel piss under the acacia trees. He’d never even completed his application to the Peace Corps, though it had arrived the week he graduated college, the product of a sudden access of enthusiasm at an informational meeting in the student union. What had held him back? Why had he let that first restless storm pass, and why had it never returned? In the end it had been Philip who’d gone off after college, Philip who’d flamed out, somewhere in the jungles of Sierra Leone, of the very Peace Corps Teddy had wanted to flame into, Philip who’d then gone backpacking across Europe for two or three stoned, meandering years before finally settling, more by accident than design, into grad school in psychology at BU. Well, that was Philip’s way. The roundabout way. The passive way. The feckless way. All those incompletes, those borrowed tuitions, those pliant, tragic-looking girlfriends, those abysmal studio apartments in the Combat Zone and the far ungentrified reaches of Jamaica Plain. Meanwhile Teddy the Elder, Teddy the Constant, Teddy the Builder, had stayed put in Carthage to—do what? Attain a secondary credential in mathematics? Buy and fix up this old house? Sit on town council, umpire Little League games at the recreation park, dig up stones in the yard on weekends and compile them into walls? Spend half his life reading about things he’d never do, and the other half doing things he’d never read about? Why? He was not the dead person, lying in a hole in the dirt. He could climb out whenever he liked. He was healthy and strong and cunning as an animal. He’d made principal at thirty-nine, the second youngest in the state. He’d put money away in tech stocks at just the right time. He could go, if he chose, anywhere in the world.

He’d gone somewhere, all right. He’d gone down to the basement. He’d eased from the covers, pulled on his sweats, grabbed his running shoes in one hand and his T-shirt with the other, and slipped out the door like a thief. Gail didn’t stir. She was a long, luxurious sleeper; her face, hazy and white, floated in the dark like a lunar nimbus. Envy of her oblivion, and maybe fear of it, sent him off to the basement, through the door, down the twelve wooden steps—he knew each one’s whiny, croaking country song by heart—and around the washer and dryer to the back room, where he flicked on the wan, solitary bulb that illumined his little gym.

True, the carpet was ragged, the walls smelled of mildew, and the windows were festooned with enormous drooping cobwebs to which insect husks clung upside down, trembling from invisible drafts. He should have swept them away a long time ago. But if his time in jail had taught Teddy anything, it was that freedom comes in paradoxical forms. One man’s arbor was another man’s cage.

He stepped on the treadmill and, with the usual mixed feelings of boredom and relief, began to run. The second hand on his watch progressed in jerks. The house was quiet and tense, like the skin of a drum. Hot air swelled his temples; old fillings and tarnished crowns rattled in his jaw. He felt like a zeppelin taking leave of its moorings. The ropes that bound him were brittle and frayed; someday soon he’d snap free. No doubt this was obvious to everyone, Teddy thought, not just the people he knew and loved but other people he didn’t know, didn’t love, and who did not in all likelihood love him. People such as Judge Tierney, and Zoe Bender, and his many enemies on the school board. Together they had not so much permitted him to take a year’s leave—his existing contract was ambiguous on the subject—as insisted in the end that he take it. For the best good of all concerned. An admirable phrase, Teddy thought. He’d have liked to know how to distinguish between the best good and all the lesser kinds.

Meanwhile he kept running. It was important to make the most of it, this down time, this underground hour in his underground lair. Because it would not last forever. Soon he’d have to engineer a return. Ascend the stairs, take his place at the family table, and pretend, as all dreamers do, that he wasn’t dreaming, that sleep was wakefulness and wakefulness sleep.

But say it didn’t end, Teddy thought. Say he remained down here, amid the cobwebs and the radon, the dull, gurgling pipes. Say the family man removed himself from the family. Let the noisy model trains of domestic life sit idle, unattended. Lost the check register. Forgot how to separate the whites from the darks. Ignored the crumbly masonry poking through the plaster; the water stains spreading like rain clouds across the perforated ceiling; the recalcitrant furnace; the leaky sump pump; the asbestos sifting from the pipe joints like so much rancid flour. But then ignoring such things wasn’t his strength. No wonder he was all in knots. Gail was right: he could let nothing go.

“Look at your hands,” she’d told him that morning. “They’re all knuckles and fists like a boxer. At night you grind your teeth so loud I hear it in my sleep.”

“I’ve always ground my teeth at night. My old man did too. It’s a genetic legacy.”

“And then there’s that other thing people do at night,” she said. “I’ve almost forgotten what it’s called.”

Teddy stared at the kitchen window, awash in his own reflection. They were doing the dishes at the time. Her remark hung like steam in the air above the sink. “I thought we agreed,” he said. “A transitional period, we decided to call it.”

“Not to be a stickler or anything, but when I hear the words transitional period, I think of something that ends sooner or later.”

“That’s my point.”

“Sometimes they end badly though, Bear. That’s all I’m saying.”

He nodded. His breath was short. It was as if he were back downstairs in his little gym, loading one more weight on the bar. Truth too was an exercise, he thought.

“Look,” he said, “the cardinals are gone.”

“Don’t take it personally. They vanish around this time every year. Sunnier climes.” She sipped her tea, eyeing him over the steam, then set it in the sink and reached for her yoga bag, a flame-colored thing bedecked with dragons. “What are you doing later? Any plans?”

“None.”

She frowned, displeased but unsurprised. It was the expression she fell into every morning, it seemed, when Mimi came down, wearing the sort of thing Mimi wore. “Come with me to class,” she said. “It’ll do you good. Cleanse the mind.”

Teddy nodded and paced, hot-eyed, like a caged panther. He didn’t want to cleanse his mind. He preferred it in its natural state: messy, congested. How galling it was to be observed from a wary distance and found guilty of hunger by the very beings he looked to for nourishment. “Maybe next time,” he said.

“Suit yourself.”

He watched her bustle down the foyer and out the door, the iron knocker bouncing crazily in her wake, like the hand of an unseen visitor. But no one was there. She was always heading off these days, always leaving home early and arriving late. At dinner she’d condescend to sit for half an hour at the table with an expression of preoccupied forbearance, glancing over the mail as she picked at one of his overspiced, labor-intensive meals. Then out the door again: a meeting, a yoga class, a book group, a friend. On weekends she’d pop out of bed, wriggle into one of her sports bras, and go off biking or swimming or running along the side of the road in her orange vest. As if leisure too were an extreme sport. Her limbs had grown sleek and hard. Even their lovemaking of late, on those occasions love was still made, seemed only another workout, a cardiovascular shortcut on the long road to sleep. What was happening to them? It had something to do with time, Teddy thought, time and space: the shrinkage of one and the expansion of the other. Something to do with all these leave-takings and disappearances, with empty rooms, silent phones. If only he didn’t hate yoga so much! But the one class he’d attended had not gone well. It was held in the basement of the Unitarian church, the same dingy, blue-carpeted space to which he used to drag his daughters to Sunday school against their wills. Now he too submitted to the larger, impersonal force. Women in leotards were poised on their mats, practicing their breathing. Teddy tried his best to attain the positions, the trembling Triangle, the ungainly Warrior, the flaccid Bow from which no arrow would ever be launched, and then those postures that came naturally it seemed to animals alone—the Lion, the Cobra, the Camel, the Upward Facing Dog, the Downward Facing Dog. But he could not hold still. He was left feeling very downward and doglike indeed, and hardly inclined to attend another yoga class should Gail ever happen to invite him again, which now of course she never would.

Earlier that week they’d gone out for his birthday to the Carthage Inn, the place one went for these things. Helplessly Teddy had looked over the menu. It was the same as last time. Nonetheless he’d managed over the course of the evening to consume a salad, a cup of gluey bisque, two sesame rolls, a humongous, fat-marbled shank of lamb, the mashed potatoes and asparagus it came with, and about nine-tenths of the crème brûlée he and Gail had agreed to split in half. His lone act of restraint came at the end, with the pale, bluish nonfat milk he poured stingily into his coffee like a rhetorical gesture. The rest he’d devoured like an animal—sopping up the juices, sucking greedily on the shank bone, furrowing out the marrow with his tongue—while Gail grazed numbly at the top leaves of her spinach salad, then consigned the rest to sleep moldering in the Dumpster. What waste. Maybe if they lived in the city there would be more to do at night and less need to indulge in these enormous, sedentary dinners that dulled the senses. But Gail’s law practice was here in Carthage, and she was happy here, or if not happy then at least more or less content with her present level of not-happiness, as opposed to the potential not-happiness of moving somewhere else, which he did not think they ever would. They’d talked about moving for years but had in fact gone nowhere. Arguably the talk itself had become a form of movement, Teddy thought, or else a substitute for it, providing just enough current to keep the raft of the possible afloat. It was hard to know.

And now it was too late. He was fifty-two. Fifty-three. The raft had become rickety, precarious; they’d flirted with the possible too long; their credibility was gone. At some point you have to stop thinking about moving, Teddy thought, sliding his gold card out of his wallet, and just live where you are. You ate your meal and drank your wine and tried to wring some enjoyment out of it before the bill came.

“Shoot,” Gail said on their way to the car, “I meant to put it on my card.”

“It’s a joint account. What difference does it make?”

“It makes a difference to me. I wanted to be the one taking you out for a change.”

“It doesn’t matter,” he said.

But in fact it did seem to matter, on some level, and his insistence that it didn’t made it matter more, not less. And now, down in the basement, running on his treadmill, he regretted his half of that conversation, and his half of the meal too, which had been more like four-fifths. The lamb was still with him. He could feel it, the carbs and proteins, the sugars and fats, settling sluggishly, like ocean sediment, in the linings of his heart. He’d be working it off for days. Both of his daughters were vegetarians; he was beginning to understand why.

He decided to keep running for another few miles and then see how he felt. The phrase came to him often these days: see how he felt. Right now as it happened he felt more or less okay, but he would take care of that.

He programmed the treadmill to its maximum verticality, so that for all intents and purposes he was running straight uphill, climbing a slope he couldn’t see toward a summit he couldn’t reach. His heart, that petulant child, pounded sullenly at his eardrums. The lungs in his chest rattled like toys. This inner hullabaloo, though alarming, was also the source of a tenuous satisfaction. He had after all bought this machine of his own free will, submitted himself voluntarily to its tedious and complicated punishments. And for what? Good health. The two words were conjoined in his mind like an arranged marriage—sturdy, dutiful, surprisingly effective. Good health, Teddy knew, was an absolute good. Not many things were. He knew this because he’d recently been forced to confront its evil twin, bad health—an incredibly clarifying experience he was eager not to repeat.

Well, he thought, get used to it. From here on life was a numbers game, an actuarial box score. Weight, body fat, heart rate, cholesterol, PSA. Fortunately he had a gift for numbers. But of course there were limits to what the numbers could tell you. Look at Philip: his numbers had been okay too. So had Don Blackburn’s, and look at him: a stroke like a bolt from the blue.

Of course in Don’s case factors of nature and nurture had to be considered. The man was fifty pounds overweight and did not own so much as a pair of sneakers. Clearly he’d made few of the compromises with age that Teddy himself had made. Don was still a smoker, a drinker, a gorger, a glutton. On bad days he’d blow through his classroom like a nor’easter, bushy-browed, all hot wind and pendulous rumbling, clogging up the aisles with his great mounded belly, his arms tossing around like tree limbs, squalls of saliva issuing from the corners of his mouth. That was what happened to English teachers. They grew indulgent as they aged, arch and capricious and mean. Don had long since lost interest in his lesson plans. He’d stand at the board making jokes the kids didn’t understand, improvising fey little couplets of dactylic verse—

Silly Miss Peters has forgotten her binder

If only Miss Cobden had thought to remind her.

He might have been auditioning for one of those fat, burdened fools—Falstaff, Lear, Willy Loman—he was always requisitioning buses and handing out permission slips to take his students to see. Don too was a mess. His face a checkerboard of distress, at once pallid and overripe; his eyes like dry wells sunk deep in his cheeks. He had never seemed all that healthy in the best of times, and it had not been the best of times for Don Blackburn, not in a long while. Now he was into the other times, the worst of times. Now you could feel the furnace of his loneliness roaring in his belly, steaming up the storm windows, pouring through the vents.

Think in terms of forgiving me everything, Don would say in his cups. God knows I do.

And Teddy had. Selflessly and tolerantly he’d endured Don’s eruptions over the years—the drunken phone calls, the retributive rants, the mawkish apologies—not because selfless, tolerant endurance of other people’s moods was one of Teddy’s specialties, though it was; not because he and Don were vaguely related by marriage, though they were; not because they’d successfully worked together at the middle school for twenty years now, though they had; or because, like most people, Teddy found both instruction and entertainment in other people’s tragedies, though he did—no, he endured them because he genuinely liked Don, and feared him, and pitied him, and felt vaguely protective of him, and, though he did not like to dwell on this, vaguely guilty toward him as well. Three years before, after a successful production of Guys and Dolls, he’d walked petite, unsmiling Vera Blackburn out to her car and wound up kissing her smack on the mouth. Right there in the parking lot, under the fizzy halo of the sodium lights! Christ alone knew why; he’d only intended to buss her on the cheek. But Vera was so short, and Teddy was so tall, and his big, lumbering weight kept moving downward as if of its own volition, the white lines of the parking grid blurring at his feet, and suddenly Vera’s fine dark hair was slipping its braid, her split ends whisking like feathers against his cheek, and it was as if they’d begun to sleepwalk their way through some strange, weightless twilight where everything was permissible and nothing quite mattered. Or was it vice versa? Of course the kiss itself lasted only a moment. And if later Teddy came to regret that kiss for ethical reasons almost as much as he’d enjoyed it at the time for aesthetic ones, on balance he was grateful for it, for the wealth of that deposit in his memory, and for the warm, tangeriney taste of Vera’s lips, which remained with him as he sailed home that night in his purring Accord. All the lights were with him. Signs bowed in the wind; mica chips glittered in the sidewalks; the shops and their awnings fell away behind him, folding up like stage flats. As if this social world with its painted signs were only another amateurish set, waiting to be struck. When he got home that night he drank a little bourbon and let Bruno out to do his business, to approach and avoid the invisible fence that ringed the yard; and then he turned off the porch light, put his glass in the sink, and went upstairs to have his way with his own lawful sleeping wife. And that was that. Not long after, Vera Blackburn moved to San Francisco and opened a maternity boutique, ripping a small tear in the social fabric through which the weather poured in on them all.

It was the sort of bad luck Don was famous for. People said you made your own luck and Teddy supposed that was true up to a point—it was why he ran on the treadmill like this every morning—but the point was not as flexible as it used to be. Nothing was, it seemed, when you were fifty-two. Fifty-three.

His heart thudded against his ribs. His right knee was showing signs of meniscus fatigue. He felt a surge in the current, a kind of electrical empathy, as if he and the treadmill were old running partners huffing their way home, and not a man alone in an insulated basement with $700 worth of sporting equipment. He gripped the handles hard, holding on. Goddamnit, here was a position he could hold: not stillness, but motion; not tranquillity, but noisy, pounding labor. Blind persistence. Putting one foot in front of the other, again and again, while the rubberized mat unfurled beneath him like the flattest, most unvarying of rivers. This he could do. Never mind his recent trials, both medical and legal. Never mind the school board. Never mind that Gail had failed to present him with a birthday present at dinner, and that there was no present from his daughters either, or for that matter no card. So what? He was a grown man, not a greedy and dependent child, mooning after the attention of his loved ones, but a vigorous, determined adult of fifty-two. Fifty-three…

Finally he’d had enough and flicked off the machine. His towel smelled salty and rank; his shirt clung to his ribs like a second skin. He left it there, rolled up on his chest, like an animal skin half-molted. Water rushed through the pipes overhead. Mimi taking her shower. By the time she was finished the hot water would be depleted, the mirror lost in steam, the bar of Lifebuoy slim as a wafer. What an uphill battle it was, getting yourself clean.