Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

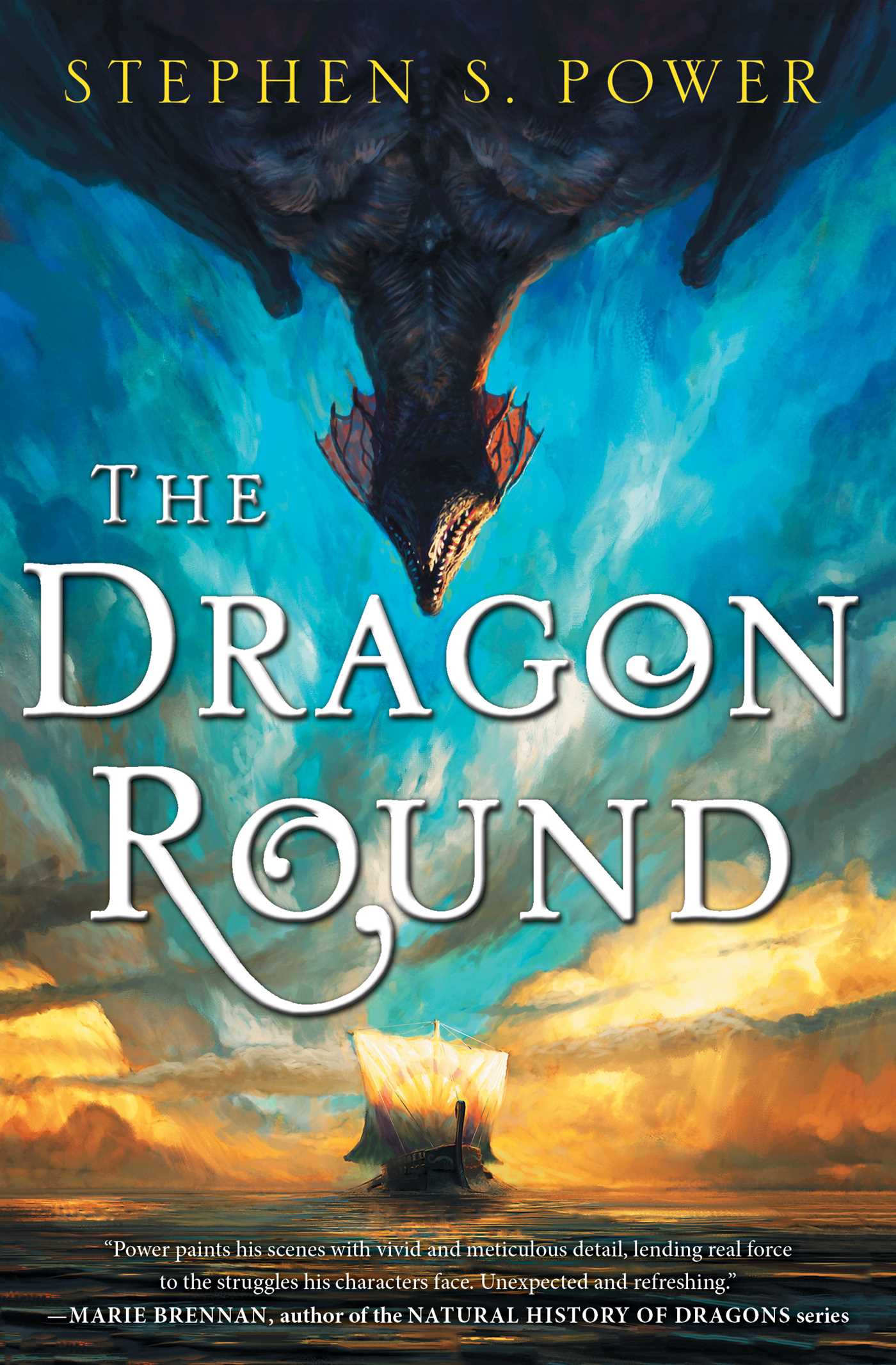

The Dragon Round

Table of Contents

About The Book

The Count of Monte Cristo with a dragon: a dark literary fantasy in which “Power paints his scenes with vivid and meticulous detail, and takes his tale of revenge in unexpected and refreshing directions” (Marie Brennan, author of the Natural History of Dragons series).

Jeryon has been the captain of the Comber for more than a decade. He knows the rules. He likes the rules. But not everyone on his ship agrees. After a monstrous dragon attacks the galley, the surviving crewmembers decide to take the ship for themselves and give Jeryon and his self-righteous apothecary “the captain’s chance”: a small boat with no rudder, no sails, and nothing but the clothes on his back to survive on the open sea.

Fighting for their lives against the elements, Jeryon and his companion land on an island that isn’t as deserted as they originally thought. They find a baby dragon that, if trained, could be their way home. But as Jeryon and the dragon grow closer, the captain begins to realize that even if he makes it off the island, his old life won’t be waiting for him. In order get justice, he’ll have to take it for himself.

From a Pushcart Prize–nominated poet and short story writer, The Dragon Round combines a rich world, desperate characters, and tightly coiled prose into a complex and compelling tale of revenge, perfect for fans of George R.R. Martin, Gene Wolfe, and Scott Lynch.

Jeryon has been the captain of the Comber for more than a decade. He knows the rules. He likes the rules. But not everyone on his ship agrees. After a monstrous dragon attacks the galley, the surviving crewmembers decide to take the ship for themselves and give Jeryon and his self-righteous apothecary “the captain’s chance”: a small boat with no rudder, no sails, and nothing but the clothes on his back to survive on the open sea.

Fighting for their lives against the elements, Jeryon and his companion land on an island that isn’t as deserted as they originally thought. They find a baby dragon that, if trained, could be their way home. But as Jeryon and the dragon grow closer, the captain begins to realize that even if he makes it off the island, his old life won’t be waiting for him. In order get justice, he’ll have to take it for himself.

From a Pushcart Prize–nominated poet and short story writer, The Dragon Round combines a rich world, desperate characters, and tightly coiled prose into a complex and compelling tale of revenge, perfect for fans of George R.R. Martin, Gene Wolfe, and Scott Lynch.

Excerpt

The Dragon Round

CHAPTER ONE

The Captain’s Chance

1

Just before dawn and still eight hours from Hanosh, the captain of the penteconter Comber feels the rowers start to flag. They’re pulling together, but behind the drummer’s beat, and if he lets them get away with it, they’ll fall apart. He can’t afford that. However exhausted they are, having rowed for seventeen hours, he brings his galleys in on time.

Jeryon’s about to leave his cabin and go below when a whip cracks and he hears his oarmaster, Tuse, call for twenty big ones. The galley lurches forward, and by the seventh heave the rowers are tight again.

Tuse has some promise. Jeryon likes that call. Not twenty for Hanosh. Not twenty to save the sick. Just twenty. Tuse focuses on the job he has, not the one he wants, unlike his other mates.

The first and second mates are on the stern deck above, two whispers through the wood. Jeryon closes his eyes to listen. So far they’ve only said what all mates say: to advance they have to earn another captain’s ship. They’re getting bolder, though. It’s a short trip from earn to take.

If Jeryon didn’t need them for the next eight hours, he’d put them off, maybe before they reached Hanosh. As it is, let them think he would sleep. Once the medicine’s unloaded, he’ll wake them to reality.

Livion, the first mate, soft-cheeked and slight, leans against the stern rail. Solet, the second, stands to starboard with the rudder trapped between his thick chest and hairy arm. They have the wind, which fills the galley’s sail and muffles the crack of Tuse’s whip.

“I wish she’d left the city,” Livion says over the wind.

“Why?” Solet says. “The flox was in the Harbor. It’d barely touched the Hill. Without some moon-eyed sailor to carry it all the way up to the Crest—”

“Plagues don’t care what lane you live on.”

“Apparently your woman doesn’t either.” Livion’s eyes narrow, but Solet ignores him and goes on. “And if her father cared before we set out, he won’t after we dock and save the city. A father might not want a sailor in his family, but what owner doesn’t want a hero in his business?”

“I’m not using her to get to him.”

Solet snorts, and Livion stiffens. Sometimes Solet oversteps himself. Hanoshi don’t discuss their private lives, which makes an Ynessi like Solet want to pry all the more. The first mate finds it easier to give in a bit and get it over with than to resist. It’s his fault, anyway, for trading a long look with Tristaban as they were casting off.

“I want him to find me worthy of command,” Livion says.

“Worthy?” Solet says. “You sound like the captain. You sound like my grandfather. There’s no worthy anymore, just worth.” Solet taps the rudder with the blade he wears in place of half his right forefinger. “Get your woman. Get your command. Get your fortune. That makes you worthy. Money is money to her father, to all the owners. You don’t want to end up like Jeryon, do you?” Solet taps the deck with his foot.

“I could do worse,” Livion says. “He’s been captain for years.”

“Decades,” Solet says, “which makes him—”

“Reliable?”

“Stalled. He doesn’t reach. He’s captain of a monoreme. Has been. Always will be. He might as well push a milk cart.”

“That milkman,” Livion says, “is the real person who’ll save the city.”

“And he’ll give the Trust all the credit for sending him. They’ll give him a pat on the head and a perk for being on time. There’s a whole city waiting to cheer us, the purest coin there is, and he won’t want any of it. Wouldn’t you want a taste of that? Wouldn’t your woman? She won’t settle for nothing, anyone can see that. You shouldn’t either.” He half closes his eyes. “We’ll have triremes.” His eyes shine. “What I could do with a trireme.”

Livion says, “I’m starting to understand the Ynessi reputation for piracy.”

“You wound me,” Solet says. “I’m no pirate. But I do need a ship to start, so once you have your woman, you could put a word in her father’s ear and see the captain rewarded with a desk while I get Comber. That I would settle for.”

Sunlight bubbles on the horizon, then erupts and flows along it. The sky is filled with blood and gold and the palest blue. The mates smile at each other.

The whip cracks again. “What about Tuse?” Livion says.

“He’ll get all the wine he can drink,” Solet says.

The portholes glow, and the cabin has gone from dark to dim. Jeryon can’t disagree with Solet. I am a plodder. I’m also fairly rewarded and content. In a city like Hanosh, where one eats well, four eat poorly, and five don’t eat at all, it’s better to be hardtack than an empty plate dreaming of steak.

He feels sorry for Livion. The boy had promise before he started listening to Solet, and probably this woman. If she’s as manipulative as Jeryon thinks, Livion will count himself lucky after the Trust learns of his plotting. He won’t get another Hanoshi ship, but he’ll be rid of her.

Solet will have to return to Yness, likely a little bruised, where he’ll be welcomed with open arms and, knowing the Ynessi, open legs. Jeryon doesn’t understand why the Trust puts up with them. A wild people. A wasteful people. At least the Aydeni on board has proven trustworthy.

The door to the adjacent cabin opens. He hears the Aydeni enter, slam the door, rattle through a box of phials and slam out again. He can imagine why she’s rattling and slamming. As an apothecary, in addition to making medicine, she has to treat the rowers, and she doesn’t approve of the Trust’s new tonic. So be it. She was only contracted for this trip. In eight hours she’ll be gone too.

As the oarmaster cracks his whip again, Everlyn climbs the aft ladder from the rowers’ deck to her cabin. Dawn does its best to cheer her, but fails. The captain won’t light the lamps, worried about Aydeni privateers, as if there were any. This makes for a gloomy ship and a gloomier rowers’ deck, however much moonlight comes through the half deck above. Gloominess suits the Hanoshi, though.

Theirs is a seafaring city that has largely traded its fishing fleet for trading galleys and its nets for coin purses, whereas Ayden has always trusted the endless bounty of its mountains: the stone and ore, the trees and game. Even the ancient shadows long to be shaped into stories featuring wondrous beasts and secret caves. Hanoshi stories are about the joy of riches and the pain of their loss. They would only shape the shadows on Comber if they could be boxed for sale.

Everlyn looks around her cabin. The small room is packed with barrels of golden shield, a curative herb they bought across the Tallan Sea. She’s spent every spare moment of the last three days turning it into medicine. The Hanoshi council will give it away for free to employed citizens. The Trust, which owns Comber, is charging the city just a nominal coin for the voyage, but this is not a selfless act. The Trust wants to become a ruling company, and ruling companies realize that if the city perishes of the plague, there will be no one left to rule or employ.

Everlyn lifts the lid of a pot simmering on the small iron stove at one end of her spattered worktable. She has spent so much of the past three days in here reducing the shield to medicine, she hardly smells it anymore. This disturbs her. Fresh, the shield smells like liver. As medicine, it smells like rotten liver. Oh, what she must smell like.

It’s a small sacrifice, though, compared to the effects of the flox, which bubbles the skin as if boiled from within, then cools into a cracking black crust. The luckiest die, and most are that lucky.

Everlyn rattles through a wooden box under the table, pulls out a clear bottle of fine red powder and pockets it. From a different box she removes a larger green bottle with a skull painted on the label and takes a long pull. She swallows a belch, chases it with another, longer pull, then puts the bottle back and goes below, slamming the door behind her. Let the privateers hear that.

Tuse stalks the alley between the rowers’ benches, so tall he shifts from hunching to squatting to both beneath the overhead. He coils and uncoils a white whip. “Fifty-seven strokes that took.”

“I’ll say it again: They’ve had too much,” Everlyn says.

“I haven’t,” one rower says, grinning wildly. A bear-claw brand glistens on his shoulder. A cut from Tuse’s lash bloodies his cheek.

“Especially you,” she says.

“You’re worried about my health?” Bearclaw says. He shakes his leg shackle. “I’m not one of them. I’ll die down here. Might as well be fired up.”

“I won’t have it,” the rower behind him says. “None of us will.” Having no shackles, he looks around. Unlike Bearclaw and the other five prisoners leased from the jail in Hanosh, the rest of the rowers wear a sodden armband with the crest of their guild, the Brothers of the Oar. “Brothers don’t cheat. Look to Hume.”

Hume is a silent mountain. His eyes are closed. He may be asleep. Yet he pulls true. The brothers have looked at him in admiration before. They aren’t as inspired now.

“I need some,” a brother says. “To get the job done.”

“And me,” another says.

“Oarmaster,” Bearclaw says, “I asked first.”

“You’ll die,” Everlyn says. “And I won’t give you the means. Or let anyone else.”

“It’s not your choice,” Tuse says. “Should I tell the Trust an Aydeni tried to sabotage the trip? How many more would you be risking then?”

Everlyn chokes on her fury. The math is easy. She’s done it with every dose of powder she’s administered: How many will she save in Hanosh for each rower she might doom on the Comber?

She takes out the bottle of red powder and a spoon. Everlyn starts aft with a prisoner, who shakes his head. Some brothers cheer until one of their own takes a huge snort.

“I said it’s to get the job done,” the brother says and stares at his oar.

Tuse grunts. Bearclaw laughs. Hume pumps the oar. The drum beats on.

Once she’s done, Everlyn tucks a stray lock of hair behind her ear, holds her chin up, and says, “I have pots to tend.” Tuse ignores her. She marches past him, climbs the aft ladder, and sees the other mates staring abaft. They look concerned. Maybe there are privateers out here.

Livion eclipses the sun with his hand and peers around it. “Do you see that? On top of the mist.”

“Too high for a sail,” Solet says. “Oh.” He squeezes the rudder tighter. “Could we outrun it?”

“It might not see us,” Livion says.

“It won’t have to. The stench of the shield will lead it right to us.” Solet curses. “Why couldn’t Comber be a trireme? We’d have marines. More weapons. Better defenses. The same speed.”

“At ten times the expense,” Livion says. “I’ll wake the captain.”

Jeryon rubs his face awake. The mates weary him, and he needs a shave too. As a man’s chin goes, so goes the man, and his will be impeccable. He puts a small towel and clay pot of soap on a shelf beneath a porthole and takes his razor, a circular copper blade, from its ivory case. It would be a ridiculous indulgence if not so useful.

Maybe Livion is worth saving, he thinks, if he could shave away the bad influences. It would also be indulgent, but he should give his mate that chance. Why should someone suffer for another man’s wrongs?

Jeryon hears Solet say, “Oh.” Through the porthole, he sees it: a tiny shadow creeping on the verge of dawn. He holds his hand at arm’s length. The shadow’s a quarter-thumb wide, no bigger than a fire ant. His stomach churns. The math is easy. If the shadow reaches the Comber, it’ll cover the entire ship.

As Livion runs overhead to the stern deck ladder, Jeryon fits the razor into its case and pockets it.

2

Everlyn dodges Livion as he slides down the ladder from the stern deck and bangs on the captain’s door. He sticks his head in briefly, then walks past her onto the causeway over the rowers’ deck. He says to Tuse below, “Silent drumming, double-time.”

Tuse glances up. “Aye.”

“And shutter the ports,” Livion says.

Tuse nods to the drummer stationed by the mast, who plays a little roll to signal the change, then taps his heavy sticks to keep the beat.

The relative silence is astounding. Everlyn is almost dizzied by the absence of pounding, as if someone had pulled her feet out from under her. She grabs Livion’s arm and says, “What is it?”

Before he can answer her, Jeryon emerges from his cabin. His black jacket emphasizes his bony frame, his red three-quarter pants reveal it, and his yellow cotton blouse, regardless of the rank its color designates, does nothing good for his pallor. His clothes have been fiercely brushed and pressed, though. His only informality is a pair of old sandals cut square in the back, Hanoshi-style. Boots are encouraged for officers on Hanoshi ships, but in his mind only Aydeni wear boots.

Jeryon tells Livion, “Break out the crossbows. Eight men to fire, two to load, and I want all sixteen loaded to start. And get the harpooners on their guns.”

Livion says, “We’re not going to run?”

“We’re running already,” Jeryon says. “It won’t make any difference if we’re seen.”

Livion knows better than to say they can’t possibly win. Jeryon admires his restraint. “I have a plan,” he says. “I hope we don’t have to use it.”

Everlyn says, “Will you tell me—”

“You’ll be told what you need to be told, when you need to be told,” Jeryon says.

She screws up her mouth and nods. He sounds like one of the Hanoshi ladies on the Crest, with their “I’ll tell you what’s wrong with me” and “I know what medicine’s best.”

“Livion, task two sailors with bringing an extra sailcloth to the poth’s cabin and a few casks of water. Now,” he turns to the poth, “cover the barrels and crates with the sailcloth and keep it drenched. If the Comber’s just a smoking hull when it reaches port, our cargo will still survive.”

“Might not be fire,” Livion says.

“Always prepare for the worst,” Jeryon says. “Makes all other outcomes seem less terrible.”

Jeryon climbs the stern deck ladder. When Everlyn turns to Livion, he’s already beyond the mast. Every word he says springs a sailor into action like a ball scattering skittles.

Everlyn scans the horizon. No privateers. Sailors pass her with the sailcloth. As they go into her cabin, she bends over the larboard rail to look past her cabin to stern. Except for a single far-off gull haunting their wake, they’re all alone.

On the stern deck Jeryon asks Solet, “Gliding or flapping?”

“Gliding. It dove a few times, then floated up again.”

“Good,” Jeryon says. “Flapping means it’s interested.”

He rubs his chin and considers the sail, a triangle the same yellow as his blouse, and the three banners dangling from the yard of the galley’s fore-and-aft rig: company, city, captain. Jeryon’s, striped blue and white, is the smallest. It’s also set at the bottom, the most easily replaced.

Jeryon says, “Steady as she goes.” He slides down the stern ladder and orders the sail and banners brought down, as he would before a storm. They’ll slow, but their profile will be smaller. Better to lose an hour from their schedule than to be seen and lose their schedule entirely.

Livion stands on the foredeck between the galley’s two harpoon cannons, bulbous iron vases mounted on steel tripods bolted to the deck. A dozen single-flue irons are stacked beside each, and a metal barrel with powder sits on the main deck, given some cover by the foredeck. Trust ships can whale if it won’t affect their schedules, which means Jeryon rarely allows it. But on this trip the cannons are meant only for defense.

When they’d set out, Livion told the crew that the Trust believed Aydeni privateers would attack them. The sailors had thought that far-fetched, regardless of the rumors spreading through the Harbor. None had imagined this alternative.

Beale, a harpooner with arms as thick as his weapon, says, “Will we fight?”

“If we do, we’ll be ready,” Livion says. “I’ll take the larboard cannon.” Beale nods.

Topp, a crossbow loader, says, “It would make a rich prize.”

“For one ship in a hundred,” Livion says. “And the one in a hundred men on it who survives. You know what happens to the other ninety-nine. Let’s not push our luck.” He heads for the stern deck.

Beale says, “I can’t think of a ship that’s done it.”

“So someone’s due, right?” Topp says. “One good shot, and you could get promoted to mate.”

“And I’d make you a harpooner so you can see how hard it is,” Beale says. “It would be an interesting shot though.” He swivels the starboard cannon, aiming over the horizon. “A whale’s a cow compared to that.” When Topp doesn’t respond, he realizes the captain is coming toward them. Topp is already pulling crossbows from compartments under the foredeck. Beale loads the cannon, but the captain takes no notice of either of them.

Solet and Livion watch Jeryon pace fore and aft to the beat of the oars. It’s maddening, his precision, but it’s better than watching the shadow slowly approach.

Solet says, “You’ve been through this before, haven’t you?”

“Yes, but not with one so big,” Livion says. “We still lost the ship.” He glances back. “Twenty-five minutes. Could be twenty.”

“If we could beat it, though,” Solet says, “would we render it? No one’s getting a share this trip. Only the captain gets a bonus. But we’d all get a taste of the render.”

“We can’t beat that,” Livion says.

“What if we did beat it?”

“We couldn’t render it,” Livion says. “Not with our schedule.”

“What’s a few extra hours?”

“The flox kills quickly. Maybe ten people the first hour, twenty the second, and so on.”

“Maybe so,” Solet says. “Maybe not. What’s a few people you’ve never met against a fortune you’ll never see again?” he says.

“I’d be happy just to keep my life,” Livion says. “Again.”

“And what’s your life now against what it could be?” He looks at Livion. “Stop thinking like him,” Solet says. “Think like the owners. The Trust would also get a share of the render. An immense share. The dragon’s share. Your woman’s father wouldn’t just bring you into the family business then. He’d give you a piece of it.”

“The only way to get it, though,” Livion says, “would be to betray the captain. And mutiny never pays out in the end.”

“Not mutiny,” Solet says. “Opportunity.”

Livion steps away. He should have Solet broken down to sailor. He would if what he said didn’t ring true. His monthly would never satisfy Trist, and to her father anyone below captain is a ship’s boy. And would the flox spread so quickly? People had been staying indoors. The city guard had been keeping the streets clear. Victims had been isolated. And all the tales he’s heard about the plague’s virulence, they could be just that, tales. Tristaban, though, she’s real.

Did he just see a flap? A grue clutches his spine.

While pacing, Jeryon keeps his head down and his eyes up so he can read Solet’s big mouth and expressive lips. He’ll deal with the second mate in a moment.

He enters the poth’s cabin. Drenched sailcloth cloaks the barrels and crates, many of which are under the table, and it’s anchored by the casks of water. He nods and notices the packets in a crate by the door. Another crate holds various tinctures and pills.

“Bandages,” Everlyn says. “I never travel without some. And medicine. I could prepare better if I knew what we were facing.”

Jeryon says, “Burns.”

She plucks some bottles from the table. “Salves.”

“And you’ll need a saw,” he says. “The carpenter will bring you one. And some cord and pins for tourniquets. Ever performed an amputation?”

Some color drains from her face. “No,” she says. “My skills are herblore and midwifery.”

Jeryon smirks. “It’s not hard. Except for the bone. And the screaming.”

Everlyn draws herself up. Color pumps into her cheeks. “I’ve pulled dead children from the living, and living ones from the dead. I’m not afraid of a little screaming.”

“We’ll see,” he says. “Stay here.”

“I think I could better serve the ship on deck.”

“How many lives have you saved while you were dead?” Jeryon says. “Stay here.”

He starts out, but turns in the doorway. He surveys the table and crates of cured shield. “All that you’ve done,” he says. “I won’t let it go to waste.” Then he leaves.

And that’s the limit of Hanoshi gratitude, she thinks. It’s not about you. It’s about what you’ve done for me.

Everlyn takes out the skull bottle and toasts the closed door. Wine shouldn’t go to waste either.

On the stern deck Jeryon says, “Where did it go?”

“Into the sun,” Livion says.

“Let’s give it a moment. You’re on the oar. If we’re seen, use your whistle to direct Tuse. It won’t matter how much noise we make at that point.”

“What about me?” Solet says.

“Larboard cannon,” Jeryon says. “A good commander leads from the front. If you want a ship of your own, you’ll need that experience.”

Jeryon sees fear flicker in Solet’s eyes. Good, Jeryon thinks, let him wonder why I’m putting him on the cannon. Solet has his faults, but everyone knows he’s better at the oar than Livion, who’s the better harpooner.

After Solet heads forward, Livion says, “Should I drop the rowers to regular time?”

“No,” Jeryon says. “That was the mistake your last captain made, thinking the danger had passed.”

Solet passes through the rows of crossbowmen lined up against the foredeck as he mounts to his cannon. They fidget. Their fingers flex. “Keep your fingers off the triggers,” Solet says. “I don’t want anyone shooting his own foot. Or mine.”

He looks past the stern deck. How long can it hide inside the glare of the sun? Could it be that smart? Or has it turned away?

Beale gestures at his cannon with his firing rod. The bent tip glows red. “Should we unload?” he says.

“You’ll know when it’s time.” Solet swivels his gun absently, its harpoon loaded and wadded well, and he thinks about how he’ll bring it down if he gets the chance. He has to get the chance. A dragon’s like a flying treasure ship. He takes his firing rod from a small steel cage containing a lump of burning charcoal to make sure it’s also fired, and he gets an idea.

As he puts the rod back in the brazier, he stabs a pebble of charcoal with his finger blade and hides it behind his wrist the way a street magician tucks away a coin. He steps over to Beale and says quietly, “Nervous?”

Beale says, “No.”

Instead, he’s terrified. They all are, but none will admit it.

Solet says, “Good. Turn around. Look at these men.” Beale does so. Solet puts an arm on the cannon behind him, and whispers, “They will look up to us when the time comes, just as we look to the captain.” He scrapes the pebble onto the touch hole of Beale’s cannon and says, “We have to be worthy, whatever comes. Are you with me?”

“Yes,” Beale says.

Solet steps to the edge of the foredeck to address the crossbowmen while waiting for the pebble to burn down. “The old man has a plan, and he sees his plans through, isn’t that right?” The crossbowmen nod. “He said we’d cross the sea in record time. And we did. He said we’d get what we needed quick. And we did. We’re nearly back in record time too”—he pauses for effect—“but for some possible unpleasantness.” The men actually grin. He’d be impressed with the captain too, if the captain were making this speech.

“We may be safe,” he says, “but if we fight, we will have a chance.” More nods. He pats Beale on the back and glances at the pebble. It’s shrunk enough to slip halfway into the touch hole. “And we will win, do you understand me?” he says. “We will bring this boat in on time, and we will complete our contract. The city needs us to.” The crossbows quiver less. “Let’s keep it down, so let me see your hands.” They pump their fists. “Let the captain.” They turn and salute him. “And if it’s still back there watching, let it too.”

The pebble burns down small enough so that when the bow smacks a large wave, it falls all the way into the touch hole. A boom roars across the waves, chased by the harpoon, which splashes uselessly into the sea.

Jeryon’s about to risk calling out from the stern deck when Solet turns on Beale. “Do you know what you’ve done?”

Beale looks from Solet to Topp to the crossbowmen and back to Topp. “I don’t know how it could have gone off,” he says. Topp’s look is especially withering. “Maybe it didn’t notice.”

They’re a hundred feet from the stern deck. Nevertheless, they all hear Livion yell, “Captain.”

The shadow rises over the sun, half a thumb wide, still so small, but coming on fast. Its wings reap the sky in twin arcs. Its sinuous neck pumps. Its claws and teeth glint like swords. Even at a mile and a half, its black scales shimmer red in the dawn.

Solet can’t see the dragon’s eyes, but it feels like the beast is staring at him.

Livion says, “Fifteen minutes, Captain. At most.”

3

Jeryon calls his mates into his cabin. They gather around a small slate-topped table. With chalk Jeryon draws an idiot’s map of the Comber: a long cigar, a triangle at one end for the foredeck, a square at the other for the sterncastle. In the center he draws a circle for the mast, surrounded by four long rectangles where the deck is open. From a shelf he grabs the only decorative thing in the otherwise sparsely furnished room: a whale tooth two hands long. It’s covered in a beautifully detailed, blue ink rendering of the Comber. Jeryon holds it behind the stern deck and says, “This is the dragon.”

Handsome piece, Solet thinks.

“It won’t attack immediately,” Jeryon says. “It’ll pass us first and maybe circle us.” He runs the tooth around the picture. “If it doesn’t find us interesting, it’ll fly away. If it stays”—he sets the tooth behind the stern deck—“we have to make it uninterested. We’ll strike first.”

“Punch it in the nose,” Tuse says. “Like a shark. I’ve used that strategy in bars.” He flexes his scarred fingers.

“Yes, but the shark punch is a myth. They’ll just eat your fist. Dragons, though—I’ve read more than a dozen reports on dragon attacks from the last decade. In the few cases in which ships have struck first, most of the time the dragons left them alone.”

“How many is ‘most’?” Solet says.

“Two out of three,” Jeryon says.

“That’s about my record in the bars,” Tuse says.

“As first mate,” Livion says, “I must remind you—”

Of course you must, Solet thinks.

“That in the event of a dragon attack at sea, company policy dictates that a galley run or otherwise avoid a fight. The insurers won’t pay out if we fight. The attack, in their eyes, would become a confrontation, not an act of nature.”

“Shall I remind you what’s happened to every ship that’s waited to fight?” Jeryon says. “Or would you care to present the report you wrote about your previous ship?”

Centered in the porthole, the dragon is as wide as Livion’s thumb. It’s diving to the wavetops to pick up speed then soaring up.

“No,” Livion says.

“How many survived?” Jeryon says.

“Eighteen, not counting me.”

“Right,” Jeryon says. “You know that I do things by the book. I trust the book. I trust the people who wrote the book. And I expect my crew to abide by the book. In this one case, though, the book is wrong. We will have to rewrite it.”

“The Trust will not be pleased,” Livion says.

“Their ship will be afloat,” Jeryon says. “Their cargo will be safe. Their city will survive. Here’s what we’ll do.” He holds the tooth a few feet over the table and flies it athwart the larboard side. “As the dragon passes, we will veer across its path.” Jeryon kicks a table leg so the table slides and the mates jump. “And startle it.”

Solet says, “Show it our side?”

“We’re not being rammed,” Jeryon says. “We want it to think we’re tough to catch. Just like a rabbit veers. Unlike a rabbit, though, when the dragon’s momentum carries it over us, we will bite its belly with a load of crossbow bolts.”

Solet smiles. “This is Ynessi.” It’s his highest compliment. Perhaps the captain can reach.

“What happens if it doesn’t lose interest?” Livion says.

“Then we turn and face it head on.”

Solet’s smile disappears. He’ll be on the foredeck, the galley’s face.

“We won’t get another shot at its belly,” Jeryon says. “The soft flesh of its face is its next most vulnerable region. The eyes. The mouth. The nostrils. Besides, there’s no room for it to land on the foredeck.”

On Livion’s last ship, a bireme called Wanderlust, a great yellow dragon lit on her stern deck and levered the prow out of the water. He remembers his captain hacking at its foot with an axe, screaming, “To me! To me!” and the creature biting him in two. His legs remained standing before the dragon licked them up, then tore the ship to pieces.

“Livion,” Jeryon says, “tell the sailors without crossbows that they’re on fire duty. They should have buckets of water and sand at the ready. Put some on each rail and some on the rowers’ deck. Then get on the oar again. Solet, you have the foredeck. Tuse, put us at regular time. We’ll conserve what energy the rowers have left. And keep the turns sharp. Quickly now.” He nods to dismiss them.

As they’re leaving, he grabs Solet’s arm. The door closes. Jeryon says, “Who fired that cannon?”

“Beale,” Solet says. “Poor gun maintenance.” He doesn’t say that he’s overheard Topp trying to get Beale to stand out so they’ll get promoted. A captain doesn’t play all his cards at once.

“And poor supervision,” Jeryon says. “A pity. I was going to report to the Trust that he could be a mate someday. And you could be a captain.” He pats Solet on the shoulder blade. “We may have to celebrate our survival with some floggings.” He nudges Solet to the door.

Jeryon checks the porthole and does some quick calculating. The dragon’s only a mile away.

Topp says, “They have the right idea.”

Scores of fins, an enormous school of hammerhead sharks, flow around the galley and past the bow.

“Wish I could swim that fast,” Beale says.

“Thanks to you, we might have to try,” Topp says.

“I didn’t do anything, Topp. Or nothing. And if I did, I don’t know how I did it.”

Topp shakes his head. His look softens. “You do know how to use that cannon, Beale,” he says. “Make it up to us. Make your shots count.”

The drumbeats drop by half and the ship slows to what feels like a dead stop. The dragon springs toward them.

On the stern deck Jeryon can smell the dragon now: old earth thrown on a fire to smother it. And he can hear its wings snap. A sail could only dream of such command over the wind. The Comber feels like a piece of driftwood.

He watches the sailors perform their various tasks and those who have completed them are checking their buckets, their weapons, even their oars. Simply having a plan, he thinks, is sometimes the best plan. It lets people concentrate on the present instead of dwelling on the future.

Livion, having nothing to check except his grip on the oar and whether his silver whistle is still hanging around his neck, makes awkward conversation. “How do you know so much about dragons?” he says.

“I read your report after you were assigned to the Comber,” Jeryon says, “which pointed me to others. I was impressed with how detailed yours was, although you didn’t elaborate on what you’d done.”

“I just led the survivors back to shore, but everyone did their part. I couldn’t take credit for it all.”

“The modesty of a second mate who suddenly finds himself in command?”

Livion shrugs. The modesty of one who lived.

“You’re lucky those men spoke up for you,” Jeryon says. “They’re the ones who put you on the Comber. You’ll never get anywhere by leaving yourself out of your reports.” He adds, “I hope I can speak up for you in mine.”

“I’ll do my best,” Livion says.

Jeryon sees he means it. There’s a chance for him yet.

The dragon’s now a hand long. “It’ll pass us to larboard,” Jeryon says. “Pipe Tuse: Larboard turn on my mark.”

Livion blows the alert.

Jeryon raises his fist to Solet, who’s little more than a thumb’s width tall at this distance. Solet says something to Beale and the crossbowmen, whom he’s spread across the front of the ship. Each has a weapon in hand, another loaded at his feet. They shout as one, “Aye!” Solet raises his fist too.

The dragon blooms into enormity in what feels like seconds. Its shadow passes them first, a black mass wider on the water than the Comber is long. Its wings come next, the color of night wine and just as fluid, but strangely delicate. When the sun catches their membranes, they glow like polished rosewood.

That was probably its original color, Jeryon thinks. Dragons blacken with age. This one’s getting on in years. It’ll know its business.

It comes abeam of the stern deck, flying twice as high as the mast, tail gently whipping behind. The dragon turns its head to better appraise Jeryon and, chillingly, so Jeryon can appraise it: wide mouth, teeth longer and sharper than a whale’s, the acrid smell of phlogiston burning through the stench of the poth’s medicine. There’s something gray lodged between its teeth and gum. Half a shark.

Its head is bigger than me, Jeryon thinks. Rain barrels could fit in its bulging eye sockets. The two skinny claws on its wing digits would make for decent short bows.

His hands, hardened by decades at sea, would make for decent hammers, though. He pounds his fist on the rail and shouts, “Larboard!”

Livion pipes the command and pushes the steering oar to starboard. The larboard oars freeze at the end of their pull, the rowers straining, the oar handles locked to their chest, as the starboard oars push forward. The Comber pivots beautifully, and the dragon lifts its wing in alarm. It drifts left to avoid them.

The galley slashes through the dragon’s shadow, and the foredeck slides under its belly like an assassin’s blade. Solet cries, “Fire!” The crossbowmen don’t even have to aim. It’s tough to miss the sky.

Eight bolts twang and thunk home at once. The dragon bucks and roars. Its tail flails down, seeking balance, and its tip, flared like a diamond, nearly flicks Topp off the boat. A thin rain of blood spatters the deck. The dragon flaps so hard that the wind from its wings presses the ship into the sea. Water convulses over the rails and washes the blood into the rowers’ deck. As the dragon passes over the starboard bow, Beale gets down on one knee, aims the cannon as high as it will go, and holds his firing rod over the touch hole.

Beale mutters, “Up, down, up,” and on the next downstroke of the massive wings, when the dragon lifts its tail and he’s just about to lose the angle, he fires. The harpoon sinks deep into its groin. The dragon roars louder, and now it’s the one beating away double-time.

The crossbowmen and sailors cheer. Topp would’ve jumped onto the foredeck to clasp Beale’s hand, but Solet orders, “Reload!”

A furlong off the starboard quarter, the dragon starts to circle the Comber.

4

As the dragon passes the sun and puts one wing to the southern horizon, Solet admires Livion’s oarwork. He didn’t think the first mate was that skilled. Steering and piping, Livion pivots the galley farther to larboard to point the prow at the dragon, then reverses the pivot to keep it dead ahead. Of course, Solet thinks, it’s in his best interests to keep the length of the Comber between himself and the dragon.

He sees what the beast is doing. A pirate ship plays games like this with traders, wondering whether they’re worth attacking. Usually, they decide yes. Ynessi can’t stand not knowing what’s inside a chest. Unfortunately, dragons also have a reputation for curiosity.

True to form, the dragon veers toward them, twice as high as the mast, its neck stretched out like a harpoon, rigid and determined.

Solet hears Livion pipe, and the drummer beat double-time, and the rowers groan, reaching the outskirts of their endurance. The crossbowmen aim over his head, and he kneels to avoid taking a bolt in the nape of the neck.

We’ve picked the lock, Solet thinks. Time to lift the lid. “No wasted shots,” he calls out.

The rowers’ deck responds with a scream and another. They sound like pirates trying to terrify a prize.

Solet counts off the yards: four hundred, three hundred . . . At two hundred the dragon drops to the height of the stern deck, wingtips skipping off the water. Its eyes slit. Solet avoids its gaze. He hears Livion piping. The galley swings to larboard. At fifty yards the dragon rears its head. It drops its jaw impossibly wide. Its teeth shimmer.

“Fire!” Solet cries.

The cannons boom. Bolts shriek. Beale’s harpoon only pricks the dragon’s thickly scaled right shoulder before spinning away. Solet’s rips through the membrane at its wingtip and keeps on going. All but one of the bolts misses the dragon’s head, glancing off its cheek or neck, but the one pins the dragon’s tongue to the floor of its mouth. The dragon half chokes on a gout of flame. Drops of fire spatter the deck and men as the dragon roars over the foredeck like an avalanche, scrambling for lift.

Jeryon stands at the front of the stern deck as Solet calls out “No wasted shots.” He’s considering whether to put up the sail again to protect the deck from its breath—could they cut away the flaming sail and let the wind blow it overboard before the mast and yard were damaged?—when the dragon drops. Jeryon sees where its line of attack will take it and thinks, The rigging. “Livion!” he yells. “Larboard! Again. Now!”

Livion sees the danger too and pipes insistently. He pushes the oar as far as it will go. The prow slides off the dragon’s line of attack. He watches Solet and Beale swivel their cannons to compensate, intent on their target. The oars don’t respond, then only Tuse is screaming and the Comber turns more sharply.

The dragon’s jaw drops, and Solet cries, “Fire!”

The dragon’s face jerks to the side, a bolt buried in its tongue. Flames spurt from the corners of its mouth. It blasts over the deck, and that’s when it sees the mast and yard. It bucks, trying to heave itself over them, but its shoulder strikes them where they meet, and catches. For half a heartbeat, the mast bends, lines groan, and the prow rears up as this great fly tries to escape the ship’s web, then the top of the mast snaps off and the dragon hurdles the stern deck. The wind from its wings crumples Jeryon and folds Livion over the steering oar, which levers its blade into the air.

On the rowers’ deck, Tuse hears Solet call out, “No wasted shots!” and he calls out himself, “You hear that? Pull harder! Ram her down its throat!”

Bearclaw screams, and the other prisoners take up the cry, an ululation born of exhaustion and blood fevered with powder. The brothers, as one, suck in a huge breath and let out their own barbaric yawp. Tuse, caught up in the moment, himself hollers. Somehow, through this, he hears Livion piping, and yells, “Quiet! Larboard! Hard! Hard!!” The rowers recover themselves and dig in. The Comber turns, then the dragon’s shadow swamps the rowers’ deck. When it smacks the mast, Tuse is flung over the drummer. The ship is wrenched to a stop.

Half a heartbeat later Tuse hears a snapping as horrible as a skull being crushed. The top half of the mast crashes through the open deck onto the rowers in the larboard quarter. One man kicks as his legs refuse to admit his torso has been crushed.

On the stern deck Jeryon looks up as the top of the mast falls into the rowers’ deck, dragging the yard behind it and toward him like a cleaver. It slices into the stern deck, grinding to a stop just before it reaches his head. He spits splinters off his lips.

The dragon is rising away. Jeryon gets up and yells to Solet, “Reload!” He looks down at the carnage in the rowers’ deck. He hears the moans of pain. “Tuse!” No answer.

Bearclaw cranes his head from under the walkway and says, “Captain. Hey. Your whipper’s conked out on the deck.” A hand emerges from the shadows and slaps Bearclaw’s bloody face. Tuse follows, the top of his head sticking out of the deck.

“We have to maneuver,” Jeryon says.

Tuse makes a quick accounting. “We’ve lost a dozen oars. Don’t know how many men. I have at least another dozen, though, to larboard. We’ll make do.”

The starboard quarter oars rise out of the water to keep the boat balanced. He’ll use them to make sharper turns when the time comes, Jeryon thinks. Smart.

“It’s coming around,” Livion says.

“Same as before,” Jeryon says. “To start.”

He stamps on the stern deck and yells, “Poth! Poth!” Her cabin door rattles, wedged shut. Jeryon calls again. The door bursts open, and Everlyn tumbles out. Jeryon says, “The medicine?”

“Good,” she says. “Me too.”

“They need you below,” Jeryon says. He points to where the mast fell.

She looks into the rowers’ deck. “I’ll get my supplies,” she says.

“And the saw,” Jeryon says.

The prow traces the dragon’s trail across the sky. It’s flying much higher now. Two hundred yards, three, four. It comes around west and heads north. Jeryon pulls in his gaze to look over the galley. “This is going to cost us another hour,” he says, “but we can make it up.”

Livion pipes an accidental note of shock.

“Never forget your schedule, Livion. Any idiot can captain a ship. It takes a real captain to bring her home on time.”

The dragon turns toward the sun and tightens the circle. Jeryon signals to Solet. Solet nods and confers with Beale and the crossbowmen. Jeryon sees Solet laugh. He’s either very confident we’re going to win or very confident we’re going to die spectacularly. That’s Ynessi.

The dragon curls in closer and closer until it’s nearly above the galley. The captain gives Livion alternate orders and has him keep the Comber in a slow larboard pivot. He watches Solet give up trying to raise the cannon high enough to target the dragon and grab a stray crossbow. That should even up the odds, Jeryon thinks.

With that the dragon tips forward, stiffens its wings, and dives.

5

The poth leaves her cabin with the crate of medicinal packets to find the dragon plunging directly at her. She clenches her butt to hold her pee, looks at the ladder, looks at the dragon, and jumps into the rowing deck.

When the dragon is three hundred yards above the galley, Jeryon says, “Now.”

Livion pipes. The galley backrows to starboard and out from under the dragon. The dragon adjusts, bearing down on the foredeck.

The crossbowmen aim as best they can, bolt points bobbing with the ship and their racing hearts. “Steady,” Solet says. The dragon extends its claws. It’s going to snatch me, he thinks. Please don’t let it take me to its nest.

Jeryon says, “Double-time.” Livion pipes. The ship jerks away again, leaving only blue water beneath the dragon.

As Jeryon had hoped, the dragon pulls up, thirty yards dead ahead and thirty yards off the waves, flinging out its huge wings and blocking the sun. It hangs there a moment, beating the air with quick, short thrusts. Solet drops the crossbow and yanks the firing rod of his cannon out of its brazier. The dragon’s head rears. Its jaw drops.

“Fire!” Solet yells. Steel rips toward the dragon’s right elbow. Liquid fire splashes behind Solet and washes three crossbowmen into the rowers’ deck on the larboard bow; the drumming stops again. Half the bolts fly high. The other half stick in the membrane of its wing. Beale’s harpoon clanks off its humerus, but Solet’s finds the mark, bearing into the joint. The dragon flinches and flaps, and the joint snaps. The outer half of the wing collapses, and the dragon falls toward the Comber. It breathes again, but the flames miss the galley, mixing a huge plume of steam with the smoke billowing from the ship. To Solet’s alarm, the fire floats, spreading around them.

The dragon’s foot reaches for the foredeck. Beale leaps off it and lands on Topp. In a tangle, they crawl along the starboard rail as the foot crushes Beale’s cannon. The ship’s bow sinks sharply and Solet is knocked down by the waves coursing over the foredeck. His crossbow is pushed toward the edge of the foredeck. Solet dives for it, slides it around to point at the dragon, and fires while on his belly.

The bolt deflects off a claw and under the cuticle, a tender spot for any creature, however immense. The dragon roars and springs from the boat, which forces the foredeck down again. Waves carry a scrabbling Solet into the sea. The dragon’s right wing flaps uselessly, and the creature lands with one foot on the forward walkway, which somehow doesn’t shatter, and the other on the starboard rail, splintering it. When it tries to grab the larboard rail with its right wing hand, the limb doesn’t respond, and the dragon topples onto the remains of the main mast and impales itself.

Jeryon watches the whole ship get swamped by the dragon’s weight. Water surges over the gunwales and into the rowers’ deck, which smothers the fires, but pours salt over the wounds of the injured. The screams below achieve a higher pitch.

The Comber bobs back up and bounces the dragon off the mast, an immense hole in its breast. It flaps once and flings itself off the galley, one wing full of air, the other full of sailors swept up by it. The dragon makes two more desperate flaps before collapsing into the sea to starboard and driving the Comber away with a huge wave. An umbilicus of blood stretches between them.

Jeryon orders, “Backrow! Larboard.”

Livion pipes. He doesn’t know what’s become of Tuse and all the larboard oars dangle lifeless from their oar holes, but there are enough brothers left on the starboard oars to respond. Unlike the inexperienced, untrained prisoners, they know the piping. The stroke is erratic to start, but after a few pulls the Comber moves farther away from the dragon—and the men in the water.

The two men floating motionless closest to the dragon appear to be dead until it picks them up. Resurrected, they flail and cry as it bites through their torsos, dribbling their heads and lower legs from the sides of its mouth.

Beale, Topp, and two others struggle to stay afloat. Like most sailors, they can’t swim. Like most drowning people, they can’t scream. Livion can’t spot Solet.

Lest they circle around, Jeryon orders, “Oars up.” Livion pipes and the ship drifts to a stop, the dragon dead ahead again. “You have the ship,” Jeryon says. “Don’t get us any closer.” He slides to the deck.

Livion sees the dragon breathe again. Flame arcs toward the captain as he runs forward. It bursts on the starboard bow an instant after he passes by, incinerating a sailor trying to throw a line to his fellows in the water. A pool of flame forms around the burning gunwale. Drops splatter Jeryon’s black coat and Livion watches him doff the smoldering garment before leaping onto the foredeck and reloading the remaining cannon.

The poth clambers onto deck, drenched, her long black hair trailing from her ravaged bun, her gray streaks tinted with blood. She needs more bandages, but the flames creeping along the starboard rail and walk are a more pressing concern. As she reaches for a bucket of sand beside the rail to put them out, a hand grasps her wrist through the rail. She starts and pulls back. The hand won’t let her go. Another appears on the rail. She’s readying the bucket to hold off the boarder when the rest of Solet appears, standing atop the ladder on the hull.

She says, “I thought sailors couldn’t swim.”

“I’m Ynessi,” he says, climbing over the rail. “We’re like tadpoles. Born in the water.” He spots the bucket and says, “That won’t work. Not for this fire.”

She reconsiders the flames and says, “I know what we can use.”

The Comber has no whale line on this voyage, so Jeryon takes up a coil of sail line and a block meant for the emergency rig. He ties the block onto the line like a fishing float then attaches the line to the harpoon through a hole near its head. He ties the other end of the line to the harpoon’s tripod.

He aims the cannon at the dragon and considers what a prize it would make. There are enough men aboard who have rendered whales that they could dummy their way through a dragon. All that bone, teeth, and claw which can be flaked into peerless blades. All that skin, so tough it can be used for armor, but light enough to wear every day. And the phlogiston, the oil secreted from glands behind its jaw that fuels its fire. With Hanosh edging toward war with Ayden it would make a devastating weapon—or it could be sold for a fortune as lamp oil. The dragon rears its head and bares its neck. Then Beale manages to cry out. Jeryon changes his mind, swivels the cannon, and fires the harpoon and its line toward the men.

The iron splashes into a wave beyond them. The block and line are just buoyant enough to keep the latter afloat despite the harpoon sinking. But the men don’t move toward it. They might not even see it. Their arms are out. They stare empty eyed at the sun, heads back, mouths open. Only Beale moves, treading water incidentally while trying to climb out of the sea. Jeryon, whose fisherman father taught him to swim before he could tie a bowline, kicks off his sandals, dives off the prow, and swims down the line.

The dragon’s wings are spread across the water, keeping it afloat, but they won’t hold it up for long. It thrashes and finds that it can drag itself toward the ship. A meal’s a meal, especially a last one. Jeryon, seeing this, swims faster.

In the poth’s cabin, she and Solet wrestle the drenched sailcloth off the tumbled crates and barrels. It’s no easy thing to drag it forward, and two firemen help. They unfold it so two can take the starboard walk and two can take the middle. When the shadow of the sailcloth passes over the rowers, they snap their heads up, worried.

The heat is tremendous, and the stench of burning oil grates at the corners of their eyes. They flap the cloth atop the flames, driving out more smoke. The sailcloth sizzles. Two more firemen bring water casks. Solet tells them to pour it over the cloth, not the flames; it’ll be easier to smother them. The flames on the walk are soon out. They hang the cloth over the gunwales, and the waves catch the end and help beat out the flames. Solet listens to the ship. He feels it through his feet. The hull still seems sound.

The poth says, “Where’s the captain?” One of the sailors points out toward the harpoon line, then to the dragon.

Solet says, “Has he forgotten his precious book?”

The poth says, “You have to help him. You can swim.”

“I lied,” Solet says. “Can’t swim a stroke. I worked my way along the side to the ladder.”

The poth looks at him in disbelief.

“What can I say?” he says. “I wanted to impress you.”

She should push him overboard, but that would only compound their problems. She grew up on a lake. She can swim well. But she knows she can’t go in after the captain. If she were lost in the water, too many aboard would die without her healing.

“He’s going to tie them to the line,” the poth says. “We’ll haul them in.”

Solet follows her and the firemen to the foredeck. The dragon won’t last much longer, he thinks. Nor will the captain. He needs to keep the former from sinking.

Jeryon considers which sailor to save first. The waves decide for him. They drift Beale and Topp farther away while pushing together the other two. As their hands touch, instead of holding on to each other, each tries to get onto the other’s shoulders. One goes under, then the next. Their backs and flailing arms appear. It’s unclear whose is whose. They disappear again. A moment later Jeryon swims through the spot. He ducks his face into the water. He only sees the murk and matter of the sea. He swims on.

Jeryon reaches Topp first. He tries to talk to him, but waves flood his mouth. Topp doesn’t respond anyway. Warily, Jeryon swims behind the sailor, a fist at the ready, then he grabs Topp around his chest. He puts up no resistance, and with a few scissor kicks Jeryon drags him to the line. He slips it under Topp’s arm. This Topp understands, and he comes to, as if from sleep.

“Go,” Jeryon says. “Climb to safety.”

“No. Beale. I have to save him.”

“Then haul us in,” Jeryon says.

Topp says “Aye,” and he pulls for the ship. A cheer goes up on board.

Jeryon swims to where the block is nearly submerged by the weight of the harpoon. Beale is ten yards away. His flailing is getting more frantic. He’ll pull me under if I get close, Jeryon thinks.

Livion watches the dragon beat toward the Comber. It either has no fire left, or it’s so intent on swimming that it can’t muster a breath. With only starboard oars, any attempt to go forward will carry the Comber dangerously close to the dragon. But, if he backrows any farther, Jeryon’s lifeline will get pulled away. Company policy dictates: Never risk the ship for a sailor. But he can’t let the captain die. And he doesn’t have to use all his oars. He pipes for just the forward three to pull, steers to larboard, and the Comber, balanced, edges toward the men in the water.

The harpoon line folds before the prow. Everlyn and the sailors, relieved that the ship is moving, take up the slack. With the dragon closing in, Solet hears Livion pipe “to arms.” But, instead of gathering the scattered crossbows and men to wield them he runs to the stern deck. Livion pipes again. Solet won’t be deterred.

Jeryon holds his hands out as best he can, trying to calm Beale. “I’m going to push you to the rope,” he says, circling the harpooner. “Don’t do anything. Look at the rope.” Beale’s eyes follow him, though. He spots the dragon beyond Jeryon, and all the fire goes out of him. He pulls in his arms, exhales, and sinks.

Saving him for a flogging, Jeryon thinks. He dives.

While Topp is being lifted onto the galley Livion searches the water for the captain. He hasn’t emerged.

Solet climbs to the stern deck. Livion says, “I have the ship, and I gave you an order!”

“Then I am acting first officer,” Solet says, “and it’s my duty to remind you—”

“I know the book,” Livion says.

“And I know the captain would have ordered you to stay away from the dragon,” Solet says.

Livion stares at him coldly. “You want him dead. Then you’ll want the dragon as a prize.”

Solet has the audacity to appear surprised. He says, “The captain and Beale may already be gone. We aren’t.”

Jeryon still hasn’t emerged. The poth, Topp, and the firemen hold the line, waiting. A few other sailors have taken up crossbows to shoot the dragon. Two bolts stick in its face. The dragon isn’t discouraged.

“Crossbows aren’t going to kill that thing,” Solet says. “We have to back water. We can watch it die from a distance. It can’t have long.”

Livion has to agree, however insolent and manipulative Solet is. Even if the captain emerges, by the time they could reel him in, the dragon would be climbing over the rail. He pipes again. The remaining rowers lift as one and pull the ship away from the dragon. The harpoon line is dragged through the water. The poth throws the slack out, leaps up, and looks pleadingly at Livion. She points at the line. There’s nothing there.

Livion tells Solet, “I want a report on the damage below in five minutes and one on the wounded in ten.”

6

As the Comber accelerates, the block at the end of the harpoon line rises to the surface. Water streams over it, more than there should be, creating a bright wake. The poth yells, “There!” A head breaks through the overflow, and another. Jeryon holds the block, and Beale holds him. The poth says, “Help me,” to two sailors nearby. Topp is already heaving at the line. The others join in. The drag is considerable, though, with the ship moving. They make little progress. And the Comber is turning, drawing the line directly across the path of the dragon.

Livion pipes double-time to get them clear. He hopes the captain and Beale can hang on. They look like bait.

Solet sees what he must do. As two more sailors take hold of the line, he sprints to the cannon. The galley is turning into the dragon’s field of fire. He grabs a powder packet from its metal storage chest, stuffs it in, tamps it down, and pulls an iron out from under the feet of the poth and Topp. As they move aside, he slams the harpoon home, grabs the firing rod, and sights, conveniently, straight down the harpoon line.

The dragon is only ten yards behind Beale, its head just above the water, its body largely submerged, which doesn’t give Solet much of an angle. For a moment he finds the harpoon aimed straight at Jeryon. No one could blame me, he thinks. It’d be like a hunting accident. Jeryon looks Solet in the eye, clearly thinking the same thing. Solet feels for the touch hole with the rod. Then Beale, exhausted, lets go of the line.

Jeryon rolls over and reaches out to grasp him, but the lightened line is easier to pull in, and Jeryon is jerked forward by the poth and the sailors. He almost loses his own grip and rolls back to dig his fingers into the block. The dragon’s head rears and its jaw drops, not for a breath, but for a big downward bite. Beale scrambles in the water. The dragon’s wings throw spray over him. It’s one stroke away from the men.

Solet has a clear shot. Topp says, “What are you waiting for?” The dragon’s head comes down. Solet fires.

The harpoon narrowly clears Beale’s head and sinks deep into the dragon’s neck. Its head snaps aside. Its neck thrashes in agony, blood spewing from its mouth. The dragon makes one last heave, glides forward, and covers Beale with its wing, trapping him under water.

Livion pipes. The oars drag the Comber to a stop. The harpoon line is pulled in and Jeryon is lifted onto the foredeck. He spits water and rolls onto his shoulder to consider the dragon. “Dead?” Jeryon says.

Solet says, “I think so.”

“Beale?”

“I don’t know.”

The dragon’s head rolls on its side, its eye open to the sun. Waves fan over the wings. A hand shoots through one of the rents in the membrane made by a bolt. Topp yells, “Beale!” The hand slips under the waves. Topp yells again, “Beale!” Now fingers appear on either side of the rent. They push it apart.

Solet says, “I cannot be seeing this.”

Beale’s head crowns then pops through. He turns and says to Topp, “What?”

Jeryon stands by the mast, sandals on again, and confers with Tuse on the rowers’ deck. The oarmaster is bruised and burned, and he’s lost a large clump of dirty, matted hair.

“All but one of our larboard rowers are dead or too injured to row,” Tuse says. “And if it weren’t for the poth—” he flicks his eyes forward to where she’s treating someone and he lowers his voice, “we’d be much worse off. Once the rigging and casualties are removed half the benches should be usable, which matches the number of oars we have left. I’ll put twelve on a side and we can get underway.”

Jeryon notices Tuse’s expression and asks, “Anything else?”

Tuse glances forward again. “More powder won’t get another stroke out of these men,” he says. “We might manage regular time, nothing more.”

Jeryon says, “We’ll spell them with sailors.”

“The guild would object,” Tuse says, “and the brothers.”

“Then they can keep their seats,” Jeryon says. “And if they can’t pull, I’ll object to the guild. But we’ll be underway in half an hour.”

“Half an hour!” Tuse says.

“We have a schedule,” Jeryon says.

Solet, who is overseeing the removal of the yard, overhears. As do several sailors watching the school of hammerheads return to attack the dragon. Its hide is tough, and they haven’t been able to do much damage, but each bite feels like a full purse gone and they still hope Jeryon will let them take it. That its wings have kept it afloat and the waves have kept it near the galley encourages them.

Jeryon considers addressing the crew on the matter and decides against it. Instead he bets himself that Solet will run to Livion as soon as the yard clears the deck. He’ll give Solet this: the second mate knows how to complain up the chain of command. And he’s smart enough not to harpoon someone in front of the crew. Fortunately, Livion is weak, but not feebleminded. He thinks like Jeryon. Livion will push Solet off, maybe relieve him. A good test of his quality.

Jeryon doesn’t know which galls him more: that he’s lost four hours from his schedule or that he needs Solet so he doesn’t lose any more.

Then again, maybe he doesn’t need Solet that much. He can’t get the image of the harpoon pointed at his head out of his mind. A different employment for Solet occurs to him.

Solet feels Jeryon’s eyes on him. He knows, he thinks. He has to know what Livion and I have been talking about. But he can’t do anything until we get to port.

On the stern deck he tells Livion, “He’s not going to render the dragon.” From up here he can see just how many sharks are roiling the water and banging against the hull. “That’d pay for all this damage ten times over. A hundred times.”

“We have to get back to Hanosh,” Livion says. “Shall I relieve you of your post? Your insolence—”

“My insolence?” Solet says. “You’re the one who left the captain to die.”

Livion struggles to keep his jaw from dropping. “You said—”

“Here’s how it will sound to the Trust at the inquiry. First, you took the ship into danger against orders, then you saw a way to confirm your new command. Who else would get the Comber but the man who brought her valuable cargo in after the ship was damaged and the captain died?”

“I’ll tell you what will go in my report,” Livion says. “How you tried to undermine the captain—”

“The captain who disobeyed the Trust’s clear rules?” Solet says. “Who attacked the dragon, who left his post to save a couple of sailors, and who risked its cargo? That’s the definition of unfit.”

“They’ll understand,” Livion says. “The city will understand.”

Solet laughs. “You’re as foolish as him, trusting up. That attitude will ruin you. We’ll all be heroes whenever we get in, however many die in the meantime, but to let a fortune slide off the rail into the sea: the Trust won’t consider that heroic. Poor judgment, they’ll say. Hardly command material, they’ll say. What would your woman’s father think?”

Livion says through grinding teeth, “Your sailors are waiting for you to remove the mast.”

“Tristaban will think you threw her away along with your career.”

Jeryon mounts the stern deck. Behind him are two sailors. He says, “This conference has gone on long enough. Solet, the rowers are exhausted. If we’re going to get in as soon as possible, the sailors will have to take a turn at the oars. As a good example, you will lead them.”

Solet says, “But I’m a mate.”

Jeryon says, “Then I won’t need to chain you to a bench.” He tells the sailors, “Take Solet to his new station.”

Solet says, “Livion.”

Whining, Livion thinks, is not Ynessi. Deception, though, is very Hanoshi. Has the captain overheard them? Has he divined Solet’s scheming? It would surely leave its stench on him. And it’s better to fire a maid, Trist once said, before the jewelry’s gone. If Solet is put in chains once he’s below, how long until I am too? If we don’t hang together now, we could hang separately later.

“Livion,” Solet says.

Livion curses Jeryon under his breath. “Belay that order,” Livion says to the sailors. “As first mate I am declaring the captain unfit for command: for disobeying the rules of engagement, for endangering the ship and her cargo, for putting us behind schedule, for abandoning his post, for doing so during an emergency, and for failing to seek reliable profit by not rendering the dragon.”

“As second mate,” Solet says, “I concur.”

“Ha!” Jeryon says. “Using the book against me. The Trust will see through that.”

“Lock him in the hold,” Livion says.

“You can’t hold me,” Jeryon says as two sailors grab his arms.

“Wait,” Solet says. He pushes out Jeryon’s arms and runs his hands over his torso and hips. Solet smiles, digs out the razor case from the captain’s pocket, and flips it into the sea. “Now we can hold you,” he says.

Whatever confusion and anger the sailors feel as the captain is dragged below is quickly replaced with the joy of avarice and potential advancement as Solet gathers a rendering crew. An Ynessi could expect nothing less from a Hanoshi crew.

“This is wrong,” Beale says. “He saved us. They’re relieving him because he saved us.”

“What could we do?” Topp says. “We just float on the waves. The mates, they are the waves.”

“At least the shares will buy us a better boat,” Beale says.

Tuse says, “Your charges are true. Your motives are nonsense. This is mutiny, plain and simple.”

Livion says, “So you’ll oppose us.”

“Yes,” Tuse says. He tightens a seeping bandage. “You can’t deal me into a game I won’t play. I won’t have him killed.”

“No one said anything about—” Livion said.

“Are you soft-hearted or soft-headed?” Tuse says, holding up a burned hand. “Do you think you can just take him to Hanosh and make your case at the inquiry? Sort this whole thing out? Have everything be normal?”

Livion says, “We’re going by the book.”

“You’re holding it upside down,” Tuse says. “Let me explain something to you: When you punch a man, you put him down. Otherwise, he’ll put you down.” He jerks his thumb at Solet. “He’d agree with me.”

Solet guides the half-completed rendering. The dragon has been tied to the galley, and, not having a cutting stage, sailors work on it from the starboard rail and the ship’s dinghy. Its head, feet, and wing claws have been hacked off with axes, wrapped in canvas, and put in the captain’s cabin. The dragon’s body is tied to the starboard rail, and is being spun so the skin can be stripped off in great sheets. This work is easier. The trick was flaking some vertebrae into blades, attaching them to handles, and using these shards, incredibly sharp and difficult to dull, to cut the skin and flay it from the meat.

Meanwhile the sharks work on the meat, exposing more bone, which they’ll harvest next.

Livion wishes he had more spit in his mouth. He says, “If we have to kill him, Tuse, we have to kill you. He’d agree with that too.”

“You don’t have the stones,” Tuse says.

“I don’t need them. See that bolt of skin?” Livion says. A sailor carries one to the captain’s cabin. “It’s worth more than the Comber. You don’t think that sailor would flay you as well if you do something to take it away?”

“You’re a good man, Livion,” Tuse says. “I like serving under you. But what you’re doing here, it’ll destroy you. The rot’s already setting in.”

Livion keeps all expression from his face. He wants to admit he’s only saying what he imagines Solet would say, but that would prove Tuse’s point. Instead he says, “Are you with us? Or him?”

Tuse slumps into his rowers’ deck posture. “My chances are better with you. But here’s my price: We give him the captain’s chance. We let the sea decide.”

“And confirm this was a mutiny,” Livion says, “not a legal action.”

“Only if he gets back,” Tuse says, “and that’s the chance we take. We’ll say he was lost overboard saving Beale. A hero’s end. Who’s to complain that it was improper? And our hands are clean.” He can see this appeals to Livion.

Livion says, “What about your rowers? Can we count on them?”

“I think so,” Tuse says. “They’ll need the money soon. The guild is finished. Soon the only rowers will be prisoners. They’re half as effective as brothers, but half the cost. And you can whip them.”

“Will they keep quiet?” Livion says.

“And risk the gibbet?” Tuse says. “Sure. But the poth won’t.”

On the rowers’ deck the poth wishes she had another bottle of wine and a sharper saw. She’s treated those who needed her help the most, and now she can consider those she thought would live regardless. She starts with a brother slumped over his oar.

Sleep is usually the best medicine. Nonetheless, Everlyn clears her throat. He doesn’t stir. Everlyn pats his shoulder. He topples slightly. She puts two fingers on his neck. It’s warm and wet and without a pulse. She raises his head. His eyes are wide and red; his lips and nostrils covered with sizzling foam the color of fire powder. Everlyn lowers his head then lowers herself to the edge of his bench.

When she looks up, Tuse is standing over her. “Livion’s waiting to see you.”

“I know,” she says. She stands up, her chin thrust at his chest. He slides aside to let her get to the ladder. “No,” she says, and heads forward again. “Let him wait. These men shouldn’t have to any longer.”

As she passes him, Tuse looks at the slumped-over rower. “This one all right?”

“He got the job done,” she says. So did I.

7

Livion orders Jeryon brought up and the dragon cut loose. They’ve rendered all they can, stuffing the captain’s cabin with bones, bolts of skin, and sheets of wing membrane. The dragon’s head has been carefully packed to ensure the phlogiston doesn’t escape, and so that it could later be made into a trophy. Crates stacked on deck are moved to the hold as soon as Jeryon emerges. Some people prize dragon meat as an aphrodisiac, but little could be taken that wasn’t ruined by the water, a dozen astounded sharks, the sandals of the renderers, and that bit which is being cooked over a brazier by the foredeck.

“Tastes like chicken,” Beale says.

“Fire chicken,” Topp says.

The rest of the carcass sinks quickly. The sharks follow it, and by the time Jeryon is marched the length of the ship past piles of stray flesh to the stern deck, the sea is empty but for the dinghy, now tied to the starboard rail.

Jeryon surveys the Comber and his crew without comment. He sees the poth in the rowers’ deck, hurrying aft. He says nothing to her either.

The mates stand together by the unmanned steering oar. The poth climbs up behind Jeryon and his escort.

“Have you come to your senses?” Jeryon asks.

Livion says, “We’ve decided to give you the captain’s chance.”

Jeryon tsks. “We’ve, Captain? There is no we in captain. Only I.”

The poth says, “What’s the captain’s chance?”

“A practice old as pirates,” Jeryon says without turning around. “The judgment of cowards.”

Livion says, “You will be set adrift without food or water, sail or oar, and the waves will decide your fate.”

The poth says, “That’s monstrous.”

“That’s prerogative,” Livion says.

“He could have me executed,” Jeryon says, “but he’s too weak.” He looks at Solet. “Pliable.”

“And you’re too rigid,” Livion says. “Four hours. That’s how long it took to render the dragon. The rowers needed the rest, too. Four hours. And a fortune. That’s what you traded for this.”

The poth pushes past the escort to stand between the mates and their captain. “And what have you traded?” She looks at them in turn. “Four hours. How many more got sick in Hanosh? How many more are dead? A body must seem awfully light when it’s weighed against a full purse.”

“I wanted to explain things earlier,” Livion says. “This isn’t your business.”

She shoots a look at Tuse. “It became mine when I signed on, but not for this. I won’t be a party to it. I’ve got enough blood on my hands.”

“Then you can take the same chance we’re giving him,” Livion says.

Jeryon says, “I didn’t want some Aydeni landlubber on this ship. I don’t want one in the dinghy either.”

“Think of her as provisions then,” Solet says. Several sailors, still armed with their gory tools, laugh.

“Stay with us,” Tuse tells the poth. “The men need you. Hanosh needs you. And you’ll get your share. You’ve earned it.”

“I don’t heal for money,” she says. “I won’t kill for it either. I’ll take the chance.”

Jeryon says to Tuse, “You don’t like this, do you?”

“It’s not the choice I would have made,” Tuse said.

“Did make, Tuse,” Jeryon says. “Putting me in a boat is one thing. Putting her in one is another. You didn’t think of that, but you can’t stop, can you?” Jeryon shakes off the escort and stands beside the poth. “She’ll be the one you see at night, not me. As for you two, if anyone cracks, if anyone lets slip what he’s done while he’s drunk in a bar, it’ll be Tuse. Then I won’t need to tell the Trust my side of the story.”

Livion and Solet give Tuse a warning look. He returns it.

The poth says, “I’d like to put on a fresh smock.”

“No,” Solet says. “And let’s check those pockets.”

“I’m going freely,” Everlyn says. “I will not be searched.”

“I could take the whole dress,” Solet says, “and give you to the sea in whatever’s under there.”

She tightens her lips and pulls from the deep hip pockets several bottles of lotion and powders. From those in the folds around her legs emerge bandages, small tools, and, improbably, two limes. From the pockets inside her sleeves come bandage ties, a pot of unguent, and packets of medicinal herbs. She drops it all in a clatter.

Solet says, “Is that it?”

“Yes,” the poth says.

“Let’s check one more place,” Solet says, “just in case.” He reaches for the thick floral brocade that extends from the deep vee of her collar. She covers her breasts. He taps her wrists. Resigned, she lowers her arms. He reaches behind the brocade and pulls from a pocket there a flat knife with a bone handle. He admires it. It’s like the full-size version of his finger blade. He pockets it.

“Is that it?” Solet says.

Again the poth says, “Yes.”

“Fool me once,” Solet says. “Hold her.” Two sailors stretch her by her arms and Solet runs his hands up each arm, over her back, belly, breasts, and broad, heavy hips, then from her crotch to her ankles. He finds no contraband. He and the crew might have taken a greater thrill from the search had her furious dignity not stiffened their hearts. The sailors let her go.

He says to Jeryon, “Pick up anything in the hold?” Jeryon yanks out his two pants pockets. They flap as uselessly as a spaniel’s ears.

Solet looks to Livion, who orders, “Put them in the dinghy.”

They’re led down to the starboard rail. The dinghy’s thwarts have been removed, as well as the collapsible mast, the rigging, and the rudder.

It seems so much larger, Jeryon thinks.

“It seems so small,” the poth mutters.

Jeryon offers the poth his hand. She refuses it, jumps into the dinghy, and kneels by the transom as he climbs in after her. He remains standing, the cords in his arms and his neck tensed. A sailor unties the painter and tosses it into the dinghy. It drifts away from the Comber.

Everlyn gets up, rocking the boat as little as possible, and stands behind Jeryon.

Jeryon says, “Livion, remember this. I don’t take chances. I plot a course, and I bring my boat in.”

“If you did take chances,” Livion says, “you wouldn’t have that one to bring in.”

Tuse descends to the rowers’ deck, Solet takes the oar, and Livion pipes. The oars extend from the galley like the legs of a crab. The ports have been reopened, but none of the rowers look at the dinghy. Livion pipes again. As the oars stroke for Hanosh, Beale comes to the rail. He can’t help it. He waves.

Jeryon calls out, “I still would have saved you.”

CHAPTER ONE

The Captain’s Chance

1

Just before dawn and still eight hours from Hanosh, the captain of the penteconter Comber feels the rowers start to flag. They’re pulling together, but behind the drummer’s beat, and if he lets them get away with it, they’ll fall apart. He can’t afford that. However exhausted they are, having rowed for seventeen hours, he brings his galleys in on time.