Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

Table of Contents

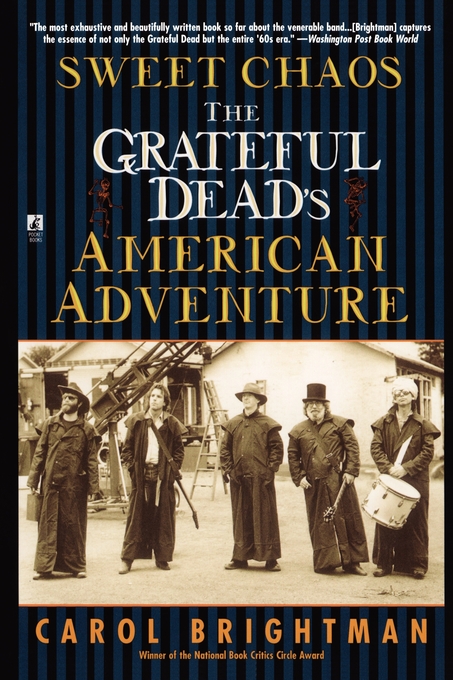

About The Book

San Francisco's Grateful Dead brought its psychedelic blend of folk, bluegrass, and blues to the 1960s counterculture, along with a romance for the Beats and a love of anarchy that made it something more than a bond. Without radio play and virtually unnoticed by the press, the Dead forged a vast underground following whose loyalty survives to the present day.

National Book Critics Circle Award-winning author Carol Brightman returns to the band's roots—to Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters, the acid tests and the heady days of Haight-Ashbury, the free concerts in Golden Gate Park and the formative shows of New York's Fillmore East—to uncover the secrets of the band's longevity. Drawing on exclusive interviews With band members, staff and crew, Deadheads, other musicians, journalists—and her own experience as a '60s activist—Brightman shows us how, amid the turbulent Free Speech Movement and antiwar rallies, the Grateful Dead's abandonment to music, drugs, and dance offered the faithful a shelter in the storm. Her riveting, in-depth portrait of Jerry Garcia, the "nonleader leader" who held to a vision of the Grateful Dead's destiny even as he recoiled from the juggernaut it became, shows us how it was that a Dead concert become something halfway between a revival meeting and a family reunion.

An absorbing and exhilarating exploration, Sweet Chaos offers, at last, a complete understanding of the Dead phenomenon and its place in American culture.

Excerpt

Rather than write, I will ride buses, study the insides of jails, and see what goes on.

Ken Kesey

Go with the flow! was the watchword in 1964, when Ken Elton Kesey, ex-wrestler, "Most Likely to Succeed" at Springfield (Oregon) High, star attraction in the Stanford University writing program, and, at twenty-nine, the author of a hugely successful first novel, lay down his pen for a more direct raid on the consciousness game. The "flow" was acid's undertow, which grabbed at the ankles like a deep current welling up from a distant shore.

"I'd rather be a lightning rod than a seismograph," Kesey told Tom Wolfe, who celebrates Kesey in The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test as "the Sun King, looking bigger all the time, with that great jaw in profile against the redwoods...." With One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, Kesey was a seismograph, recording vibrations from deep within the culture. The novel's mental hospital, presided over by Nurse Ratched, is a supple metaphor for the politics of adjustment, which dominated the 1950s. Anything that fouled the smooth workings of the "Combine," as Kesey calls the tyranny of consensus -- with its impersonal, clinical face, not so different from the 1990s -- was crushed.

Now he was messing with the vibrations themselves. "Tootling the multitudes," he called his early raids on the cultural mainstream, which included, on one occasion, turning up in Phoenix, Arizona, during the 1964 presidential campaign decked out in American flag regalia and waving a huge placard saying, A VOTE FOR BARRY [Goldwater] IS A VOTE FOR FUN.

Nineteen sixty-four was the year Kesey took to the road in the 1939 International Harvester bus, which today lies moldering like a giant turnip in a ravine on his Oregon ranch. The gaily painted 1948 replica stands in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, next to Janis Joplin's Porsche. In the summer of 1964, speed freak Neal Cassady was the designated driver of the original bus, as he had been for Kerouac and his gang in the 1940s and '50s, when the long-distance vehicle of choice was usually an old jalopy. Cassady, who was famous for streaking through the night as his companions slept -- the car's left-front wheel cleaving the median line while the chassis shimmied at ninety miles per hour -- was useful for another reason. He tied the new hipsters not only to the glorious past but also to a blue-collar Dionysian fantasy (which is where the Hell's Angels come in) that winds like a holding stitch through American bohemianism. Packed with Pranksters like a fun house on wheels, the magic bus, Furthur (as it was called), circumnavigated the country in a slipstream of lysergic acid, dispensing more roadside mayhem in that breakaway year than a circus on the run.

In 1964, the ground the Pranksters shook was already heaving underfoot. The summer of 1964 was when the rebel '60s can he said to have parted company with the '50s. The New Left broke away from the old Left, and from liberals -- first at the Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City, where liberal Democrats sold the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party down the river (or so the rebels believed), thus ending a brief but historic alliance between blacks and whites. The second turning point came with the shelling of an American destroyer in the Gulf of Tonkin by a North Vietnamese PT boat, followed by massive U.S. air attacks on North Vietnamese bases in reprisal. Almost overnight, President Lyndon Johnson parlayed the Tonkin Gulf encounter into a major incident, and sailed a de facto declaration of war through a largely liberal Congress. The third turning point arrived with the triumph of the Free Speech Movement (FSM) on the University of California's Berkeley campus in the fall of 1964.

It was this trio of prophetic events that social historian Todd Gitlin suggests gave birth to the "[radical] movement's expressive side," along with "the politics of going it alone, or looking for allies in revolution... [and] the idea of 'liberation'; the movement as a culture, a way of life apart." Here is when the seeds of what would later be called "identity politics" were sown; also the idea of the personal as political. At the same time, the very notion of "a way of life apart" was intensified by the arrival of psychedelics.

Kesey and the Pranksters were soon to demonstrate that, as Berkeley's Free Speech organizers feared, drugs could divorce the will from political action. But LSD produced other, more ambiguous effects. Once ingested, "the force of acid itself could not be denied, or forgotten, or assimilated. It hung there, apart from the rest of experience, terra incognita, a gaping hole in [the] mental maps," writes Gitlin, an early president of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), who couldn't have made this observation without having tasted the forbidden fruit.

While street acid turned up on college campuses around 1965, it would be a few more years before it found its entry point into the student movement. But when LSD did work its "magic" on radical political consciousness, it fed on a vision of change not so different in form from the one that gripped Kesey's crowd. "Change was seen as survival," another former SDS president, Carl Oglesby, recalls. And "nothing could stand for that overall sense of going through profound changes so well as the immediate, powerful and explicit transformation you went through when you dropped acid." Just as breaking through the barricades redefined you as a new person, so, too, might taking LSD.

Meanwhile, it's funny how the psychedelic bus trip is never mentioned in the same breath with the year's climactic political occurrences, as if culture and politics run on separate (tenured) tracks, which by and large they do. (The proliferation of black, feminist, and "queer" studies, which view "politics" altogether differently, offer no exception.) In popular history, headlines are reserved for the arranged event: not the magic bus, but the Beatles' 1964 appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show. Political milestones mark the triumph of law, like the passage of 1964's Civil Rights Act, rather than landmark steps toward political change, such as the formation of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party.

In The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, Tom Wolfe mythologizes the Merry Pranksters in prose that is irradiated by the gee-whiz wonder of a bigtime acid trip. But he also makes the shrewd observation that with their Day-Glo-painted, superstereo'd bus, the Pranksters, far from dropouts, were scouting the perimeters of postwar America's "Neon Renaissance." "It was a fantasy world already, this electro-pastel world of Mom& Dad&Buddy&Sis in the suburbs," he writes:

There they go, in the family car, a white Pontiac Bonneville sedan -- the family car! -- a huge crazy god-awful powerful fantasy creature to begin with, 327-horsepower...[S]o why not move off your snug-harbor quilty-bed dead center and cut loose -- go ahead and say it -- Shazam! -- juice it up to what it's already aching to be: 327,000 horsepower, a whole superhighway long and soaring, screaming on toward...Edge City, and ultimate fantasies, current and future...

"You're either on the bus or off the bus," said Kesey. (Or "you're either on the bus, off the bus, or under the bus," fixing it, a veteran of the 1964 trip recalls.) And the party bus, for that's what it was, just as preprohibition LSD was mainly a party drug, was actually the Pranksters' Bonneville sedan. It was the extended-family car (like the painted vans that would later follow the Grateful Dead). "'Better Living Through Chemistry,' is how we were brought up," remembers Gene Anthony, the photographer who memorialized the Summer of Love in Newsweek in 1967. "Mind expansion, you say? Sure, I'll take a pill."

For Kesey, the early trips were travel on a grand scale. I took these drugs as an American," he tells me, speaking not of the Acid Tests but of the government experiments administered at the VA hospital in Menlo Park in 1959-1960. And he likens himself and his fellow travelers to Lewis and Clark heading west. "Jefferson," he says, "wanted to know what's goin' on out here. We were the same kind of people. Like Lewis and Clark, we were trying to go into this unknown land, chart it and come back and report it as clearly as we could." Their explorations took place in weekly sessions where they were paid between twenty and seventy-five dollars a day -- "more each time to keep you coming back," says Robert Hunter, who also signed up -- to test-drive a batch of what the government called "psychotomimetic [madness-mimicking] drugs."

Psilocybin was the first hallucinogen Kesey was administered. Mescaline and LSD followed, interspersed with other psychotropic drugs. Their tendency to turn household objects into monsters sometimes toppled the subject into his own horror movie. Hunter, however, a lover of horror comics who takes his hat off to anyone who can scare him, responded to this portion of the menu with gusto. "I was beset by monsters," he says happily, remembering the day a locker door flew open inside the VA hospital and Dracula stepped out. "I knew I was hallucinating," he says, and wondered, "What can you do with this?" He fantasized a crystal dagger, and "Plunged it into my heart. I pulled it out, dripping with blood....And that's not all," he says. I saw an elevator shaft. I jumped down it. This was great fun. I was never, ever frightened of psychedelics," Hunter assures me; at least when he was alone and free to hobnob with demons from his subconscious. "It's entertaining," he says, "to have them out there."

When he was in a crowd of people, it was a different story; and Hunter remembers a "horror trip" he had in 1966 at the Trips Festival, which was a two-day Acid Test minus the acid (though everybody brought their own), beefed up by the involvement of crusader Stewart Brand and the budding impresario Bill Graham. Sitting in a cold sweat in the vortex of a churning sea of costumed freaks, wondering why he had dropped acid in such a setting, he was drawn to a sentence forming on the wall: OUTSIDE IS INSIDE. HOW DOES IT LOOK? Kesey, who was adept at steering beginners away from paranoid trips, had inscribed it on an overhead projector. Suddenly, everything was okay. If outside was inside, inside could be outside -- and the awful trip was only a projection.

Hunter doesn't want me to think his visions were all horror stories, because they weren't. Even in the clinical setting of the VA hospital, he went "all the way," seeing "God and all that good stuff." The VA interviewers wanted to know whether any of the drugs increased his susceptibility to hypnosis, and so they tried to hypnotize him-before, during, and after the doses, never successfully. During one session, tears had poured out of his eyes, and the clinician asked why he was crying. "I'm not crying," Hunter explained. "I'm in another dimension. I'm inhabiting the body of a great green Buddha and there's a pool that is flowing out of my eyes."ar

Kesey had nothing but comtempt for the government people in their white coats, carrying clipboards and asking inane questions, "who didn't have the common balls to take the stuff themselves. So they hired students. All the other guinea pigs, not just me," he asserts, "knew that what was happening was as important as anything that's happened this century, and maybe in the last five hundred years." "What was happening?" I ask. And Kesey shifts into the present tense, as if what I'm after is a piece of the action, which, in a way, I am. (The gin and tonics on the kitchen table between us are a poor substitute for the chemicals we're discussing.)

A kind of tartar builds up over your consciousness, and you think this is the world. This isn't the world; this is just tartar, a wall, a buildup of scum and shit. People come along who have great power and they knock a hole in that. And through that hole comes this blinding bolt of light, and you see it and you remember, Oh, I FORGOT about that. I keep being drawn back into this Procter and Gamble world.

Who punched the hole through the wall?

Kesey doesn't miss a beat. Garcia opened the hole. Cassady kept punching this hole, he says, naming the heavenly choir; and the light that comes through it makes you realize that we're not trapped in the Newtonian Pat Buchanan world. There's another thing that's happening. And the only way to survive as a nation is to become HEALTHY in this way, to not be hung up in the flesh, and with all this stuff that Buddha and Mohammed and Christ and everybody always warns you against --

Stop, I say, unsettled by all these Names. I've just figured out the connection between Lewis and Clark and the men in white coats. They were testing you, and you were testing IT!

Kesey nods. Yeah, he says. These people are members of the establishment, all the way back to the twelfth century. These were doctors, government people. It took us about two trips to realize, THEY DON'T KNOW SHIT!...Then at a certain point the government says, I don't like the looks of these kids after they've been taking this stuff. Let's make it illegal. We were in the midst Of an experiment, he finishes. We still are.

The initial experiments had been launched by the Central Intelligence Agency, which began to investigate mind-altering drugs and parapsychology in 1953 under the auspices of a James Bondish program called MK-ULTRA. MK-ULTRA, in turn, had its roots in the Office of Strategic Services's (OSS) wartime fascination with so-called truth drugs like mescaline, scopolamine, and liquid marijuana. The first of the government's Acid Tests were carried out on workers at the Manhattan Project, whose security was deemed sufficiently dense to ensure the secrecy of the new mind-control program. Later, MK-ULTRA's drug research was conducted mainly at prisons and mental hospitals.

By 1959-1960, when Kesey was dosed with psilocybin, mescaline, and LSD, the CIA had started farming its research out to VA hospitals and the Army Chemical Corps. In university cities like Palo Alto and Boston, where both the CIA and the Army carried out testing programs at institutions connected to Stanford and Harvard, volunteering for an LSD trip became the hip thing to do. By 1965, over two hundred research studies were under way throughout the country, many involving military personnel (not always knowingly), and some whose investigators were engaged in a good deal of self-experimentation.

A few months before my trip to Oregon to see Kesey and Mountain Girl, The New Yorker had run an item about a visit Kesey and Ken Babbs had paid their old pal Timothy Leary in Beverly Hills. Leary, who was dying of prostate cancer, had turned his customary Sunday-afternoon drop-in into an Irish wake, with the Departed One receiving. Kesey, whose birthday it was, toasted his "great mentors": Neal Cassady, Allen Ginsberg, Jerry Garcia -- and Leary. "We were all ringside while you made history," he told the frail old hoofer. Then he offered a second toast, to the CIA.

I asked Kesey whether he was referring to the Menlo Park experiments -- which he was -- and whether he knew then that the CIA was behind them. No, he said. Allen Ginsberg used to tell them this, but nobody believed him until the Freedom of Information Act unlocked the evidence. How did Ginsberg know? I asked. "Ginsberg was one of those little ferrets," Kesey said, "and he had a lot of other little ferrets under him, and they ferreted out a lot of this stuff." When the proof arrived, Kesey had said, "Of course, of course." Now, he submits, "that's how you know there are angels and other beings, because irony suggests a humor from above." His mind caterwauls ahead. "And when you see something like the Grateful Dead spreading acid around that the CIA has brought into the country [which isn't exactly what happened, but Kesey's not a stickler for detail], you can feel the irony, and can get a little giggle out of it yourself."

Hunter appreciates the irony, too. "You betcha," hes says when I marvel over the unexpected creativity of government military research. "They created me for one thing. And Kesey and the Acid Tests."

With his traveling road shows, Ken Kesey was a genuine trailblazer. An interesting American type, he belongs to the frontier, albeit a frontier of literature and vaudeville, like Paul Bunyan or the Medicine Man. He reminds one of the Wizard of Oz -- and is, in fact, in a video he produced a few years ago called Twister, which is modeled on The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. Twister borrows liberally from Grateful Dead lyrics, and it treats what Kesey calls "end-of-the-millennium angst," though he himself abides by happy endings. "Sometimes the light's all shining on me," the Wizard belts out in a finale, scored after Jerry Garcia's death:

Other times I can barely see

Lately it's occurred to me

What a glorious trip it still do be, do be, do be, do be!

With the magic bus and the Acid Tests, Kesey cut a spur in America's open road. Travel, psychedelics, music, lights, costume, dance, and the gang -- together they begat the magic bundle that the Grateful Dead would carry through ballrooms and old vaudeville halls, gyms, sports arenas, and giant coliseums over the next thirty-odd years. His fateful move was to have introduced LSD, via the Acid Tests, to San Francisco's rock 'n' roll community, rather than keep it within Prankster circles, or drop it on the politically charged community across the Bay.

There, on the University of California's flagship campus, another path was being cut through the increasingly bureaucratized routines of college life in the 1960s. After U.C. chancellor Clark Kerr enforced his September 1964 gag order against politicking on the Berkeley campus, four hundred student protesters seized Sproul Hall and turned it into a "liberated zone," projecting Chaplin movies on the walls, smoking grass in the stairwells, and listening to folksingers in the halls. The next day, helmeted riot police dragged the students from the building, thus anointing the Free Speech Movement with the power of dangerousness.

Berkeley's movement was led by students who had worked with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in the Mississippi voter-registration projects of the summer of 1964. There, among unlettered sharecroppers who were regularly terrorized by Ku Klux Klan night riders, these middle-class kids had acquired a respect for the moral and political power of resistance that was not easily forgotten when they returned to school. An echo of the struggle being waged in the South can be heard in FSM leader Mario Savio's words:

There is a time when the operation of the machine becomes so odious, makes you so sick at heart, that you can't take part; you can ' t even passively take part, and you've got to put your bodies upon the gears and upon the wheels, upon the levers, upon all the apparatus and you've got to make it stop. And you've got to indicate to the people who run it, to the people who own it, that unless you're free, the machine will be prevented from working at all.

Addressing an audience of eighteen thousand in Berkeley's Greek Theater in October, Chancellor Kerr put forth his vision of the academic community as a "knowledge factory," designed to create socially productive individuals. It was not a vision destined to win favor with his listeners, but Kerr's real mistake came afterward, when Savio, a philosophy major who had worked with SNCC in Lowndes County, stepped to the rostrum to invite everyone to a rally where the speech could be debated. Before he finished a sentence, he was grabbed by two cops and wrestled to the floor. The next day, the faculty senate voted overwhelmingly to accede to the FSM's demands, which centered on the campus community's right to organize support for the civil rights movement.

One of those collective peak experiences had been reached -- Columbia University SDS's takeover of Fayerwether Hall four years later would be another -- when students were seized by the exhilaration that came from mass rebellion to imagine they had broken through the ivy wall into a wider world, where anything was possible. It was a "frame-breaking experience," recalls the FSM's self-styled "mystical propagandist," Michael Rossman -- not unlike an acid trip. Only in this case, the "frameworks of individual perception" were broken "by willfully and collectively changing social reality." And Rossman, referring to the spontaneous decision of a crowd of students to prevent the police from hauling off a manacled protestor, summons up the "transcendent hours around the police car which crystallized a new consciousness among us." Out of that had emerged "an entity, a thing distinct from our selves": the Free Speech Movement. Thus had they been relieved of some of the "terrible and naked responsibility" for all that was happening, "as if to say, 'it's not me doing this, it's the FSM.'"

Like the hole punched in Kesey's wall of "scum and shit," the confrontation with authority enlightened and empowered the Berkeley students to undertake hitherto-undreamed-of tasks. FSM's Free University, hammered out by students sitting cross-legged on civil defense drums in the basement of Sproul, was one result of the Berkeley strike. A counterinstitution born of revolt -- of chaos -- it was the first of many Free Universities and Alternate U's to emerge in the wake of protests during the years ahead. But the more important effect of the uprising was the transformative power of civil disobedience.

Berkeley's wasn't the era's first successful political confrontation. The demonstrations on the steps of San Francisco's City Hall in May 1960, opposing the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) investigations, broke the ice. Nationally, the Greensboro, North Carolina, sit-ins in February of that year sparked the dynamo that turned a portion of the younger generation's sense of alienation, of dffierentness, into the opposition politics of a committed minority. But the direct action of Berkeley students in the fall of 1964 -- the year the first cohort of baby boomers reached college age en masse -- cast a long shadow over the 1960s.

For the community grouped around Kesey in what Mountain Girl calls "our little island in La Honda," it was a shadow to be reckoned with; and it was, in a confrontation the following year. What happened when U.C. Berkeley's Vietnam Day Committee invited Ken Kesey to address an allday antiwar teach-in on October 16, 1965, is reported in The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test (an account Kesey confirms in its essentials). He had arrived late in the afternoon in the bus, accompanied by a dozen Pranksters wearing scraps of Army surplus, tooting horns and twanging guitars. Awaiting his turn behind the platform, Kesey had contemplated the speakers; "shock workers of the tongue," Tom Wolfe calls them, who addressed the crowd (about fifteen thousand filling Sproul Plaza) "while the PA loudspeakers boomed and rabbled and raked across them." For Wolfe, the political rally is a farce: "toggle coats, Desert Boots, civil rights, down with the war in Vietnam" -- it's all one cigar. Kesey, in his big orange highway worker's coat and Day-Glo-painted World War I helmet, is the nitty-gritty.

Among the "workers of the tongue" is M.S. Arnoni, who wears a prison uniform to commemorate the family he lost in a concentration camp in World War II. If the dead "could call out to you from their graves or from the fields and rivers upon which their ashes were thrown," he tells the crowd, "they would implore this generation of Americans not to be silent in the face of the genocidal atrocities committed on the people of Vietnam." Bay Area radical Paul Jacobs is next, and from where Kesey stands, only his voice is heard "rolling and thundering, powerful as Wotan, out over that ocean of big ears and eager faces...."

Wolfe delivers a cool, deflating slap to the cheek of '60s radicalism, and then, driving in deeper, draws forth from an antiwar teach-in, via counterrhetoric, a fascist rally. Kesey is joined by Paul Krassner, The Realist's editor, who is a fan. Together, they take in Paul Jacobs: "omnipotent and more forensic and orotund and thunderous minute by minute -- It is written, but I say unto you...the jackals of history -- ree-ree-ree-ree..." They don't know what he's saying, but they "can hear the crowd roaring back and baying on cue, and they can see Jacobs, hunched over squat and thick into the microphone, with his hands stabbing out for emphasis, and there, at sundown, silhouetted against the florid sky, is his jaw, jutting out, like a cantaloupe."

Krassner plays Horatio to Kesey's Hamlet: "You could not help being drawn, almost physically, toward him," he says; "like being sucked in by a vast, spiritual vacuum cleaner."

Nodding toward Jacobs, Kesey says:

"Look up there,"..."Don't listen to the words, just the sound, and the gestures...who do you see?"

And suddenly Krassner wants very badly to be right...."Mussolini...?"

Yep.

"You're playing their game," Kesey drawls into the microphone when it's his turn to speak. "We've all heard all this and seen all this before, but we keep doing it," he says, honking on a harmonica in between lines. "It" is "the cry of the ego," which is "the cry of this rally!...Me! Me! Me! And that's the way wars get fought," he continues, because of "ego...because enough people want to scream pay attention to Me....Yep, you're playing their game." As for Vietnam, "There's only one thing to do. And that's everybody just look at it, look at the war, and turn your backs and say...Fuck it."

It was a strange performance; and the message, given the time and the place, was about as far from the brute actuality of the fighting in Southeast Asia, and the concerns of the rising antiwar movement, as one could get without falling off the grid. For the Pranksters, however, it was a coup. "The whole reason to go to Vietnam Day was more to participate in an event where a lot of people would be than to actually protest the war," Mountain Girl contends. "We weren't thinking about the war," she says. "We were mostly interested in getting our piece of the turf where we could get in there and maybe get some of these poor antiwar maniacs over here and have some fun." In Berkeley, the Pranksters were on a recruiting mission: "The idea," says Mountain Girl, "was really to subvert people to our way of thinking."

The anti-antiwar sentiment had its own roots. Ken Babbs had recently returned from Vietnam, where he flew helicopters high on psilocybin, according to Kesey, who had kept him supplied. "He didn't want to line up and take a shot at the military he had just served," Mountain Girl states. Nor were the Pranksters ready to go up against the Hell's Angels, those weird centurions who provided them, and later the Grateful Dead, with a kind of instant karma of outlawry in the Bay Area. Many of the Angels had also been in the service, she points out, and were passionate about believing "the United States shall rule the world." Skip Workman, who had arrived in Oakland on the USS Ranger, an aircraft carrier out of Norfolk, Virginia, in 1957, was one of them. In 1965, when he was vice president of the Oakland club, he and a half-dozen Oakland Angels "took on ten thousand demonstrators" who were marching from Berkeley to the Oakland Army Terminal -- which they never reached, until another march in 1967.

When Berkeley radicals came to the Pranksters' compound in La Honda, Mountain Girl remembers sitting there "in amazement," listening to them talk politics. "It was all so serious....We were busy studying LSD with the party God," she says, "trying to learn how to do it really right, how to have incredible parties." The Pranksters operated in a different force field, one that flowed from their sense of themselves as embattled artists, "creative, sensitive, crazy people," she maintains, who knew "America was a very thorny environment" for what they wanted to do. To sow riot? I ask, thinking of Johnny Appleseed (and of Berkeley). Yes, she says, but "a riot of color, a jungle, a garden. I mean, it was just like, God, we gotta get somethin' goin' here!" And she grins in remembered anticipation.

Copyright © 1998 by Carol Brightman

Product Details

- Publisher: Gallery Books (September 1, 1999)

- Length: 368 pages

- ISBN13: 9780671011178

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

Washington Post Bookworld The most exhaustive and beautifully written book so far about the venerable band...[Brightman] captures the essence of not only the Grateful Dead but the entire '60s era.

David Gans host of The Grateful Dead Hour and author of Conversations with The Dead Anybody who ever wondered about the Dead and Deadheads should read Sweet Chaos to understand why the significance of this culture cannot -- and should not -- be underestimated.

Boston Globe Brightman is on engaging stylist....She knows how to put words to some of the more ethereal elements of the Dead world -- the vibe, the energy, the indescribable acid journey.

Robert Christgau Los Angeles Times Book Review I found Brightman's retelling swift and compelling. And for a literary scholar to describe any species of rock and roll with such clarity, delicacy, and detail is a mitzvah, if not a miracle.

Publishers Weekly (starred review) Entertaining....A cogent, intelligent look at the Dead and the deep structure of American culture into which they so successfully tapped.

Village Voice The author [has] precisely the near distance that a Dead book needs in order to transcend, while tasting, the obsessions of the band's cult...the strength and freshness of Brightman's book lies in her ability to articulate the band's considerable significance to the unHead.

New York Observer [In] the chapters called "Their Subculture and Mine," Ms. Brightman offers something unexpected and rare: a moving, believable evocation of the despair that gripped New Left activists between 1970 and 1972, and an honest critique of their often panicked responses to that despair.

Booklist One of the best books for devotees and pop culture vultures alike....An engrossing treatment of the Dead and their times....Throughout, Brightman offers fresh perspectives and insights and captures the flavor of the band.

Raleigh News & Observer (North Carolina) [A] valuable, smart and ethically engaged account of political and cultural resistance in the '60s as a necessary preamble to what came next.

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Sweet Chaos Trade Paperback 9780671011178(0.3 MB)