Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

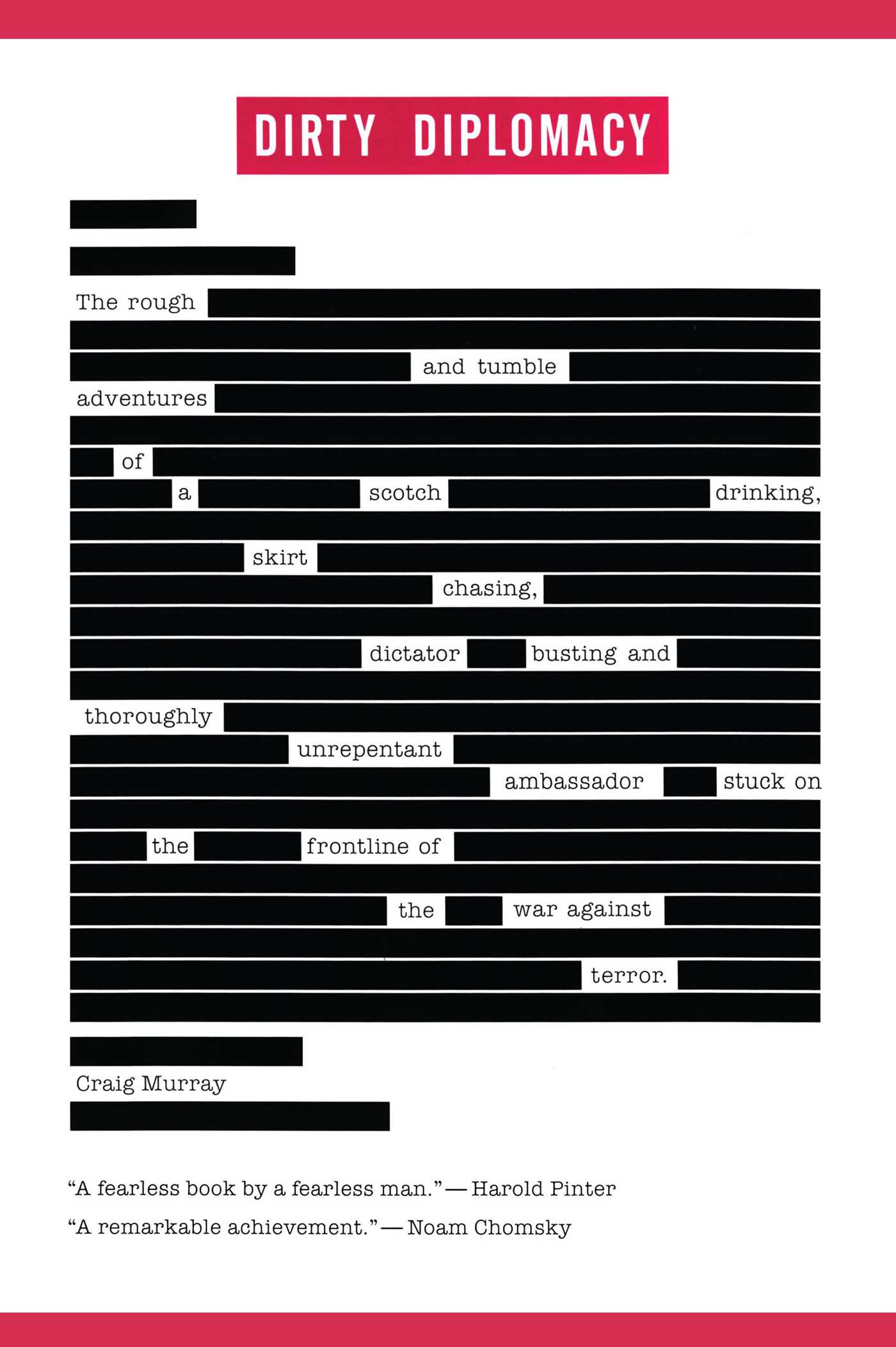

Dirty Diplomacy

The Rough-and-Tumble Adventures of a Scotch-Drinking, Skirt-Chasing, Dictator-Busting and Thoroughly Unrepentant Ambassador Stuck on the Frontline of the War Against Terror

By Craig Murray

Table of Contents

About The Book

With all the pace and drama of a political thriller, Dirty Diplomacy is a riveting account of a young, fast-living ambassador's battle against a ruthless dictatorship in Central Asia and the craven political expediency in Washington and London that eventually cost him his job.

Craig Murray is no ordinary diplomat. He enjoys a drink or three, and if it's in the company of a pretty girl, so much the better. Murray's scant regard for the rules of the game also extends to his job. When, in the first few weeks of his posting to the little-known Central Asian Republic of Uzbekistan, he comes across photographs of a political dissident who has literally been boiled to death, he ignores diplomatic nicety and calls it for what it is: torture of the cruelest sort.

Murray soon discovers that this is no one-off incident: fierce abuse of those opposing the government is rife. It's not long before he is tearing around the country in his embassy Land Rover, shaking off Uzbek police tails and crashing through roadblocks to meet with dissidents and expose their persecutors. He even confronts the despotic president, Islom Karimov, face-to-face.

But Murray's bosses in London's Foreign Office, ever mindful of their senior partners in Washington, don't want to upset the applecart. Karimov is an ally in the newly announced Global War on Terror. His country is host to a big American air base. The last thing they need is a battling young diplomat stirring things up. In Craig Murray, that's exactly what they've got...

Craig Murray is no ordinary diplomat. He enjoys a drink or three, and if it's in the company of a pretty girl, so much the better. Murray's scant regard for the rules of the game also extends to his job. When, in the first few weeks of his posting to the little-known Central Asian Republic of Uzbekistan, he comes across photographs of a political dissident who has literally been boiled to death, he ignores diplomatic nicety and calls it for what it is: torture of the cruelest sort.

Murray soon discovers that this is no one-off incident: fierce abuse of those opposing the government is rife. It's not long before he is tearing around the country in his embassy Land Rover, shaking off Uzbek police tails and crashing through roadblocks to meet with dissidents and expose their persecutors. He even confronts the despotic president, Islom Karimov, face-to-face.

But Murray's bosses in London's Foreign Office, ever mindful of their senior partners in Washington, don't want to upset the applecart. Karimov is an ally in the newly announced Global War on Terror. His country is host to a big American air base. The last thing they need is a battling young diplomat stirring things up. In Craig Murray, that's exactly what they've got...

Excerpt

CHAPTER 1

Awakening

CHRIS LOOKED SURPRISED.

“OK, let’s go” was not a standard reaction from a British ambassador to the news that a dissident trial was about to start. The Land Rover drew up to the embassy door and out I went, still feeling pretty uncomfortable at people calling me “sir,” opening doors and stopping their normal chatter as I passed.

We turned up outside the court, whose small wicket entrance led through an unprepossessing muddy wall into a dirty courtyard containing several squat white buildings. Like much Soviet construction, it looked unfinished and barely functional. To enter the courtyard we had to give passport details to two policemen sitting at a table outside the gate. They took an age to write down details with a chewed-up pencil in an old ledger. I was to find that the concealment of terrible viciousness behind a homely exterior was a recurring theme in Uzbekistan.

About a hundred people were hanging about the courtyard waiting for various trials to begin. I was introduced to a variety of scruffy-looking individuals who represented different human rights organizations. Their dress was eccentric even in the ethnic and social kaleidoscope of Tashkent, ranging from tweed, and sweaters apparently knitted poorly out of old socks, to garish Bermuda beachwear with fake designer specs. Oddly, the seven or eight I met seemed to belong to the same number of different organizations, and most of them would not talk to each other.

One short but distinguished-looking man, with a shock of white hair and big black specs, was so self-important he wouldn’t talk to anyone at all. Chris, bustling round doing the introductions, pointed to him and said, “Mikhail Ardzinov—he says it is for you to call on him.” I was puzzled, as the question of who called on whom involved taking about eight paces across the courtyard. Chris explained that Ardzinov was feeling very important, as his group was the only one that was registered, and thus legal. The others were all illegal. Peculiarly, Ardzinov’s registered group was called the Independent Human Rights Organization of Uzbekistan. None of this meant much to me at the time, and I certainly hadn’t been an ambassador long enough to feel my pride mortified by taking eight paces, so I went and shook the man’s hand. I received a long, cool stare for my effort.

But even at first meeting, some of these people could not help but impress. One gentleman had been a schoolteacher until he was thrown out of his job for refusing to teach the president’s books uncritically. He now spent time at trials of dissidents, normally the less reported ones in obscure places. He documented them painstakingly by hand, and sent details to international organizations. I asked how he lived, and he said largely on the kindness of others. Judging by his clothes, gaunt face and sparse frame, that kindness was a limited commodity. I asked if he was not in danger of arrest. He said he had spent “only” a total of four months in custody in the past three years. An unhealthy flush burned in his cheeks and his eyes alternated between a normal genial twinkle and flashes of real anger. They were unforgettable, yet they are not the eyes I saw that day which haunt me still.

Nor are Dilobar’s. Lovely as she was, I am afraid I cannot recall her eyes. But mine had been drifting during the conversation to her full but graceful figure in blue as she stood under an old corrugated-iron canopy to my left, tall and striking amid a group of older local women in their flowered dresses, velvet jackets and hijabs—a colorful Muslim scarf that in Uzbekistan covers the hair but none of the face. Her fine black hair flowed long and free down her back. Her cotton dress was full, reaching right to the neck, wrists and sleeves, and of a light flowing blue, though close fitting around her slim waist.

Chris brought her over and introduced her as Dilobar Khuderbegainova. Something was hammering insistently at my dulled senses. What was wrong—Khuderbegainova—Oh! This was the sister of the victim of this show trial. Yes, her eyes were filling with tears. Her brother was going to be executed, and I was checking out her legs through her dress. I was filled with self-loathing.

She said with great dignity that her brother was a good man, and the whole family would remember me for coming. I thanked her and held out my hand. Another mistake. Muslim women don’t shake hands with strange men. For a moment she was taken aback but then she held out her hand and clenched mine firmly, and a smile almost troubled her lips. I wanted to say, “Don’t worry,” and promise to help, but realistically, what could I do—and if I could do nothing, why was I there?

Chris was looking at me curiously.

“Bit hot,” I said, and went and sat down under a tree to think. My momentary self-hate turned to real anger against a system that tortured thousands and executed hundreds, and against fellow diplomats for their complacent acquiescence.

We waited two hours in the heat for the trial to start. It was 111 degrees in the shade that day, and we didn’t have much of that in the courtyard. There was a sudden bustle of activity, then we entered through a door that led straight onto stairs down to a basement. The atmosphere changed completely. The short staircase was lined with perhaps a dozen paramilitaries—Ministry of Interior forces—in gray camouflage, carrying machine guns. There was so little space left to pass that a tense scrum developed. I was only about three steps down when one of the militia, for no reason I could discern, pulled me back by the arm. I snapped. Wheeling round, I grabbed him by the throat and pushed him back against the wall (modesty requires me to point out that he was a very small militiaman). I raged uselessly in English, “Don’t you touch me, do you hear? Do not touch me.”

Silence fell, and everyone looked aghast. I don’t think the militia knew who I was, but I was obviously foreign and therefore probably not shootable. These people pushed others about all their lives, and no one ever pushed back. My little militiaman gave a nervous laugh, and chatter started up again. We carried on down to the courtroom as though nothing had happened.

The atmosphere in the courtyard had been apprehensive but resigned. Now all was tension. The six prisoners were already in the “dock.” This was a large cage, constructed roughly out of what looked like concrete reinforcing rods welded together, not straight but strongly, and lots of them. It had been painted white in situ, with lashings of paint so thick they had oozed down the spiraled grooves in the rods, and congealed there in pendulous blobs. The concrete floor around it was heavily spattered. The cage door was fastened with two enormous padlocks. Fourteen heavily armed militiamen stood shoulder to shoulder around the cage. The six accused squatted inside on what looked like two low school benches, with not quite enough room for the three men on each.

Loved ones tried to push between the guards to say a few words of encouragement. The accused barely turned their heads, though some managed wan smiles. All were gaunt, clean-shaven with shorn hair. Five looked middle-aged and, from the ripples of skin, as though they had once been better fleshed. Their hair was whitening. The sixth, Khuderbegainov himself, looked like a teenager (he was twenty-two). He coughed periodically and cast his eyes around quickly and furtively, in contrast to the languor of the others. He looked very skinny indeed.

Of the six, three had already been in jail for some two years. The charges were multiple, but different permutations of the six were charged with a number of different offenses. For example, three were charged with the armed robbery of a jeweler, four with the murder of two policemen. All were charged with attempting to overthrow the government and undermine the constitution.

This was one of a series of trials of Muslim activists in Uzbekistan. I knew some of the statistics already—Human Rights Watch alleged some seven thousand political or religious prisoners. I had heard allegations of torture, but not in detail. In three weeks of Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) and other U.K. government briefings prior to my taking up post, there had been scarcely a mention of human rights, and none of torture. The briefing I had been given put the emphasis first on FCO internal management procedure, second on Uzbekistan’s supportive role in the War on Terror and third, on Central Asia’s economic and commercial potential in hydrocarbons, gold, cotton and agroindustry. I could have written a paper on hydrocarbon pipeline options for Central Asia, but nothing had prepared me for the reality of the “War on Terror” as I was about to encounter it.

In the courtyard I had met a helpful young man called Ole, from Human Rights Watch, who let me share his Uzbek interpreter in the court. He filled me in on some background that I later checked out. Two of the people charged with murder had actually been in jail at the time, serving their sentences for “religious extremism.” And over a dozen other people had already been convicted of these murders. There was no suggestion that they were in conspiracy, or even knew each other, or that the murders had been carried out by a mob. The simple Uzbek government tactic was that a genuine crime (and two policemen had indeed been murdered) would be used to convict lots of opposition people. And they would, of course, not be listed as political prisoners but common murderers, rapists or whatever. In that year—2002—some 220 prisoners were officially executed in Uzbekistan, in addition to those murdered in police or security service custody, in prison, or who simply “disappeared.”

The courtroom was chokingly hot. I felt beads of sweat running down my shirt. The judge looked like First Goon out of central casting: swarthy and thick-set, floppy hair swept back, dressed in black trousers and a white shirt that strained at his belly. He started out with a harangue at the prisoners for wasting the court’s time.

The jeweler who had suffered the armed robbery said that three of the men, wearing balaclavas, had tied him up and held him, robbing him of an improbably large sum of money. They had shot at him with pistols but missed. A defense lawyer asked him why no bullets or bullet holes had been found in the room. The jeweler supposed rather weakly that the bullets had gone out the window. As he was allegedly tied up on the floor at the time, the defendants must have been very bad shots indeed. The defense lawyer was making hay with this.

The judge had been ostentatiously not listening whenever the defense spoke, whittling at his fingernails with his knife or chatting with the rapporteur, who equally stopped writing whenever the defense said anything. But somehow it must have penetrated the judge’s thick skin that this prosecution witness was not going down well. He interrupted the defense lawyer with a sharp rebuke, and then instructed the defendants to stand.

He harangued them again, saying that they represented evil in society. They were thieves and murderers who sought to undermine Uzbekistan’s independence and democracy. Their list of crimes was long and it would be better if they admitted it. He concluded that he was astonished that they had found the time to commit so many crimes, when they had to stop to pray five times a day. He evidently considered this a hilarioussally and guffawed loudly, as did the prosecutor, rapporteur and various other cronies. But I noticed a few narrowed eyes among the militiamen. Later he again amused himself hugely by interrupting a defendant: “I don’t suppose anyone could hear you through your long Muslim beard,” snapped the judge. “I see the prison service removed it for you!” He several times told the defense to shut up and stop wasting time.1

The jeweler was asked to identify which three of the six had robbed him. He peered uncertainly at the benches—plainly he had no idea. Pressed by the defense, he managed to identify—and the odds against this must be high—entirely the wrong three. This got the judge very angry.

“You are mistaken, you old fool!” he bellowed.

The judge then read out the names of the three who were charged with this particular crime, and asked them to stand.

“Are these the men?” he asked the terrified jeweler, who stammered his assent.

“Let the record show they were positively identified by the victim,” said the judge.

This was pure farce, but I had to pull myself back to the terrible reality behind this bizarre charade. These six nervous men stood to be shot. The family would not be informed of the execution, so for months would not know if their loved one was dead, believing him perhaps dead while he still languished, and perhaps alive when he was well rotted. This was a deliberately refined cruelty as was the practice—inherited from the Soviets—that when the family was finally informed of the death, they would be charged for the bullets that killed him.

It was at this minute I was caught by those eyes I will never forget—they were Khuderbegainov’s. He had spotted me in the crowd, a Westerner in a three-piece suit, out of place and time. Who was I? Maybe this strange apparition brought some kind of hope. Maybe the West would do something. Maybe he wasn’t going to die after all. The drowning man had caught a fleeting glimpse of straw on the surface. His eyes bored into mine, small, dark, intense, filled with a desperate hope. He was urging me, with every mute fiber of his being, to do something. I looked back. I don’t do telepathy, but stared at him, trying to say: “I will try, in God’s name, I will try,” with my own eyes. He smiled and nodded, a confidence shared, and then looked away again.

Again, I suffered a wave of self-loathing: What am I doing here? What right have I to give false hope—is that not just one more cruelty?

BUT THIS MOMENTARY doubt was replaced by an iron resolve—I would help; I would work tirelessly to stop this horror in Uzbekistan. I would not spend three years on the golf course and cocktail circuit. I would not go along with political lies or leave the truth unspoken. The next bit of the trial set that resolve, like catalyst added to epoxy resin.

An old man was assisted to the witness stand. He had a little white beard and sparse white hair, and wore a black lacquered skullcap and a dull brown quilted gown. He was shaking with fright. One of the accused was his nephew. His statement was read out to him, in which he confirmed that his nephew was a terrorist who stole money to send to Osama bin Laden, and had traveled to Afghanistan to meet Bin Laden.

“Is this your testimony?” asked the prosecutor.

“But it’s not true,” replied the old man. “They tortured me to say it.”

The judge said that accusations of torture had been dismissed earlier in the case. They could not be reintroduced.

“But they tortured me!” said the old man. “They tortured my grandson before my eyes. They beat his testicles and put electrodes on his body. They put a mask on him to stop him breathing. They raped him with a bottle. Then they brought my granddaughter and said they would rape her. All the time they said, ‘Osama bin Laden, Osama bin Laden.’ We are poor farmers from Andijon. We are good Muslims, but what do we know of Osama bin Laden?”

His quavering voice had become stronger, but at this he physically collapsed and was helped out. The judge then stated that the prisoners’ connection with Osama bin Laden was not in doubt. They had confessed to it.

I had seen enough and left. Those three hours in court had a profound effect on me. If these were our allies in the War on Terror, we were not on the clear moral ground that Blair and Bush claimed so braggingly.

I SENT A TELEGRAM back to London, explaining in detail what I had seen at the trial. Shortly thereafter, a sentence of death was passed on Khuderbegainov and long sentences given to his “accomplices.” The Human Rights Policy Department in the FCO agreed we should take up the case, and the wheels clunked into motion for the long process of agreeing to an EU démarche, or formal protest.

In the meantime, Dilobar and her father came to my office. I welcomed them, accepted their thanks for attending the trial and said that I had been shocked by what I saw. I asked the father what they could tell me by way of background to the trial.

This was the first time I had encountered a phenomenon that was to bedevil me for the next two years: the inability of Uzbeks in human rights cases to tell their story in a plain, concise manner. This is well recognized by those working in the field. Various reasons are given—sheer terror at saying anything against the government, the effect of social shaming and the cultural propensity for roundabout storytelling. But the phenomenon is very real, and frustrating.

The Khuderbegainovs, a well-established Tashkent family, were previously in favor with the regime. The father was a former head of a Tashkent state radio station. He told me the story of when he had been arrested for questioning. They came for him while he was attending a family wedding. He was in tears as he told this, and seemed unable to get past his despair at being arrested in such a humiliatingly public fashion, and his astonishment that a wedding should be violated.

Weddings hold an important position in most cultures, but Uzbek society takes this to extremes, with a family not infrequently spending three years’ income on a daughter’s wedding. So no doubt it is very bad form to violate one. But the poor man, holding back his tears, had spent thirty minutes telling me nothing but that he had been arrested at a wedding. With his son sentenced to death, this was hardly the most important point.

I therefore asked Dilobar to continue the story. I learned from her that her brother had received an education at one of the Saudi-funded Arabic schools opened in Tashkent in the 1990s. Following the bombings there in 1999,2 these schools were closed down and many of their pupils and former pupils imprisoned. Eventually this well-connected family received warning that her brother was to be arrested, and he ran away to Tajikistan, where he made contact with rebel groups. From there he was sent to Afghanistan to fight with the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) alongside the Taliban, but he didn’t like what he saw and ran away from there too.

For a year he scratched out a living as a bazaar trader before eventually being arrested crossing the Tajik/Uzbek border. He was then imprisoned for some months in Uzbekistan and severely tortured, which had caused permanent liver damage. Under torture he had confessed to the range of crimes featured in the trial. The family had not known he was taken until the trial began. During the period of imprisonment, the father himself was imprisoned. His brutal interrogation ostensibly focused on the whereabouts of his son, who in fact was already in custody at the time.

I judged that Dilobar believed this story herself. I wondered whether this was the whole truth about Khuderbegainov’s involvement with the IMU and the Taliban, but even if it wasn’t, he plainly had not received a fair trial on the charges for which he had been sentenced to death. I thanked the impressively composed and articulate Dilobar and her father, and promised to do what I could. We had already decided to move for an EU démarche, but I was racking my brains for further action that might forestall the execution, and decided to contact the UN.

THE NEXT DAY Chris came into my office and tossed a brown envelope onto my desk.

“You may not want to look at these—they’re pretty horrible,” he said.

I was beginning to understand enough about the country to have an inkling what might be in the envelope, and I waited until the cook, Galina, had brought in my cappuccino and biscuits before opening it. It contained a number of photos of a naked corpse, a heavy, middle-aged man. His face was bruised and bloodied, and his torso and limbs were swollen and a livid purple. He was such a mess that it took a little while for me to work out what I was looking at. I said a short prayer, rather to my own surprise.

I then went back through to Chris’s office.

“Where did we get these?”

“His mother. That’s Mr. Avazov. He was a prisoner in Jaslyk gulag, right up in the desert. That’s where they take the hard-line dissidents. Anyway, his body gets delivered back to his mum in a sealed metal casket. She’s ordered not to open it and to bury it the next day. A local militsiya is left to guard it. Anyway, militsiya man falls asleep and Mum sneaks down, gets the casket open, body onto the kitchen table, and gets out the Kodak.”

“Without waking up the militsiya man?”

“He was probably drunk.”

“Look, Chris, I don’t know what happened to this poor bugger, but I think we should go big on this one. I really want to get serious with this regime, and this could be the case we need. But we have to be certain of our ground.”

Chris mused, “The photos are pretty good. I am sure Alistair in Human Rights Policy Department in London said that they could get pathology reports done, if they had good enough photos.”

“Great. Try it.”

MY APPEARANCE AT the Khuderbegainov trial had caused quite a stir. Ambassadors in Tashkent just did not attend dissident trials. It brought Matilda Bogner, head of the local office of Human Rights Watch, to the embassy to see me. Matilda was a pleasant Australian in her early thirties, with a broad open face, long brown hair swept back into a ponytail and a penchant for peasant dresses.

“They tell me that you’re not like a normal ambassador,” she opened.

“I certainly hope not,” I replied. “I am struggling to work out what this embassy actually used to do all day.”

“Not a lot,” she said. “Chris is good, but I think he was pretty well frustrated.”

She filled me in on the human rights situation, and it was grim. No opposition parties, no free media, no freedom of assembly, no freedom of religion, no freedom of movement. Not only were exit visas required to leave the country, you needed an internal visa or propusk in your passport just to leave the town where you lived. Matilda reckoned there were, at an absolute minimum, seven thousand people imprisoned for their religious or political beliefs. She filled me in on the cases of Elena Urlaeva and Larisa Vdovina, who had recently been committed to a lunatic asylum for demonstrating outside the parliament. Both were now strapped to their beds and receiving drug treatment that amounted to a chemical lobotomy.

I thanked Matilda, and said I hoped we would be able to work closely together. I asked her about the attitude of other embassies. She said the U.S. embassy was in denial. It viewed President Karimov as an essential partner in the War on Terror, and had convinced itself that he was a democrat. Of the other embassies, only the Swiss really gave a stuff about human rights. Unfortunately, the countries that genuinely cared about human rights—the Scandinavians, Dutch, Irish, Canadians and Australians—didn’t have embassies in Uzbekistan.

A FORTNIGHT LATER, Chris received the report on the photos of the corpse of Mr. Avazov. The pathology department of the University of Glasgow had prepared a brief but detailed report of their findings. The victim had died of immersion in boiling liquid. It was immersion rather than splashing because there was a clear tidemark around the upper torso and upper arms, with 100 percent scalding underneath. Before he was boiled to death, his fingernails had been ripped out and he had been severely beaten around the face. Reading the dispassionate language of the pathology report, I was struck with a cold horror.

© 2006 Craig Murray

Awakening

CHRIS LOOKED SURPRISED.

“OK, let’s go” was not a standard reaction from a British ambassador to the news that a dissident trial was about to start. The Land Rover drew up to the embassy door and out I went, still feeling pretty uncomfortable at people calling me “sir,” opening doors and stopping their normal chatter as I passed.

We turned up outside the court, whose small wicket entrance led through an unprepossessing muddy wall into a dirty courtyard containing several squat white buildings. Like much Soviet construction, it looked unfinished and barely functional. To enter the courtyard we had to give passport details to two policemen sitting at a table outside the gate. They took an age to write down details with a chewed-up pencil in an old ledger. I was to find that the concealment of terrible viciousness behind a homely exterior was a recurring theme in Uzbekistan.

About a hundred people were hanging about the courtyard waiting for various trials to begin. I was introduced to a variety of scruffy-looking individuals who represented different human rights organizations. Their dress was eccentric even in the ethnic and social kaleidoscope of Tashkent, ranging from tweed, and sweaters apparently knitted poorly out of old socks, to garish Bermuda beachwear with fake designer specs. Oddly, the seven or eight I met seemed to belong to the same number of different organizations, and most of them would not talk to each other.

One short but distinguished-looking man, with a shock of white hair and big black specs, was so self-important he wouldn’t talk to anyone at all. Chris, bustling round doing the introductions, pointed to him and said, “Mikhail Ardzinov—he says it is for you to call on him.” I was puzzled, as the question of who called on whom involved taking about eight paces across the courtyard. Chris explained that Ardzinov was feeling very important, as his group was the only one that was registered, and thus legal. The others were all illegal. Peculiarly, Ardzinov’s registered group was called the Independent Human Rights Organization of Uzbekistan. None of this meant much to me at the time, and I certainly hadn’t been an ambassador long enough to feel my pride mortified by taking eight paces, so I went and shook the man’s hand. I received a long, cool stare for my effort.

But even at first meeting, some of these people could not help but impress. One gentleman had been a schoolteacher until he was thrown out of his job for refusing to teach the president’s books uncritically. He now spent time at trials of dissidents, normally the less reported ones in obscure places. He documented them painstakingly by hand, and sent details to international organizations. I asked how he lived, and he said largely on the kindness of others. Judging by his clothes, gaunt face and sparse frame, that kindness was a limited commodity. I asked if he was not in danger of arrest. He said he had spent “only” a total of four months in custody in the past three years. An unhealthy flush burned in his cheeks and his eyes alternated between a normal genial twinkle and flashes of real anger. They were unforgettable, yet they are not the eyes I saw that day which haunt me still.

Nor are Dilobar’s. Lovely as she was, I am afraid I cannot recall her eyes. But mine had been drifting during the conversation to her full but graceful figure in blue as she stood under an old corrugated-iron canopy to my left, tall and striking amid a group of older local women in their flowered dresses, velvet jackets and hijabs—a colorful Muslim scarf that in Uzbekistan covers the hair but none of the face. Her fine black hair flowed long and free down her back. Her cotton dress was full, reaching right to the neck, wrists and sleeves, and of a light flowing blue, though close fitting around her slim waist.

Chris brought her over and introduced her as Dilobar Khuderbegainova. Something was hammering insistently at my dulled senses. What was wrong—Khuderbegainova—Oh! This was the sister of the victim of this show trial. Yes, her eyes were filling with tears. Her brother was going to be executed, and I was checking out her legs through her dress. I was filled with self-loathing.

She said with great dignity that her brother was a good man, and the whole family would remember me for coming. I thanked her and held out my hand. Another mistake. Muslim women don’t shake hands with strange men. For a moment she was taken aback but then she held out her hand and clenched mine firmly, and a smile almost troubled her lips. I wanted to say, “Don’t worry,” and promise to help, but realistically, what could I do—and if I could do nothing, why was I there?

Chris was looking at me curiously.

“Bit hot,” I said, and went and sat down under a tree to think. My momentary self-hate turned to real anger against a system that tortured thousands and executed hundreds, and against fellow diplomats for their complacent acquiescence.

We waited two hours in the heat for the trial to start. It was 111 degrees in the shade that day, and we didn’t have much of that in the courtyard. There was a sudden bustle of activity, then we entered through a door that led straight onto stairs down to a basement. The atmosphere changed completely. The short staircase was lined with perhaps a dozen paramilitaries—Ministry of Interior forces—in gray camouflage, carrying machine guns. There was so little space left to pass that a tense scrum developed. I was only about three steps down when one of the militia, for no reason I could discern, pulled me back by the arm. I snapped. Wheeling round, I grabbed him by the throat and pushed him back against the wall (modesty requires me to point out that he was a very small militiaman). I raged uselessly in English, “Don’t you touch me, do you hear? Do not touch me.”

Silence fell, and everyone looked aghast. I don’t think the militia knew who I was, but I was obviously foreign and therefore probably not shootable. These people pushed others about all their lives, and no one ever pushed back. My little militiaman gave a nervous laugh, and chatter started up again. We carried on down to the courtroom as though nothing had happened.

The atmosphere in the courtyard had been apprehensive but resigned. Now all was tension. The six prisoners were already in the “dock.” This was a large cage, constructed roughly out of what looked like concrete reinforcing rods welded together, not straight but strongly, and lots of them. It had been painted white in situ, with lashings of paint so thick they had oozed down the spiraled grooves in the rods, and congealed there in pendulous blobs. The concrete floor around it was heavily spattered. The cage door was fastened with two enormous padlocks. Fourteen heavily armed militiamen stood shoulder to shoulder around the cage. The six accused squatted inside on what looked like two low school benches, with not quite enough room for the three men on each.

Loved ones tried to push between the guards to say a few words of encouragement. The accused barely turned their heads, though some managed wan smiles. All were gaunt, clean-shaven with shorn hair. Five looked middle-aged and, from the ripples of skin, as though they had once been better fleshed. Their hair was whitening. The sixth, Khuderbegainov himself, looked like a teenager (he was twenty-two). He coughed periodically and cast his eyes around quickly and furtively, in contrast to the languor of the others. He looked very skinny indeed.

Of the six, three had already been in jail for some two years. The charges were multiple, but different permutations of the six were charged with a number of different offenses. For example, three were charged with the armed robbery of a jeweler, four with the murder of two policemen. All were charged with attempting to overthrow the government and undermine the constitution.

This was one of a series of trials of Muslim activists in Uzbekistan. I knew some of the statistics already—Human Rights Watch alleged some seven thousand political or religious prisoners. I had heard allegations of torture, but not in detail. In three weeks of Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) and other U.K. government briefings prior to my taking up post, there had been scarcely a mention of human rights, and none of torture. The briefing I had been given put the emphasis first on FCO internal management procedure, second on Uzbekistan’s supportive role in the War on Terror and third, on Central Asia’s economic and commercial potential in hydrocarbons, gold, cotton and agroindustry. I could have written a paper on hydrocarbon pipeline options for Central Asia, but nothing had prepared me for the reality of the “War on Terror” as I was about to encounter it.

In the courtyard I had met a helpful young man called Ole, from Human Rights Watch, who let me share his Uzbek interpreter in the court. He filled me in on some background that I later checked out. Two of the people charged with murder had actually been in jail at the time, serving their sentences for “religious extremism.” And over a dozen other people had already been convicted of these murders. There was no suggestion that they were in conspiracy, or even knew each other, or that the murders had been carried out by a mob. The simple Uzbek government tactic was that a genuine crime (and two policemen had indeed been murdered) would be used to convict lots of opposition people. And they would, of course, not be listed as political prisoners but common murderers, rapists or whatever. In that year—2002—some 220 prisoners were officially executed in Uzbekistan, in addition to those murdered in police or security service custody, in prison, or who simply “disappeared.”

The courtroom was chokingly hot. I felt beads of sweat running down my shirt. The judge looked like First Goon out of central casting: swarthy and thick-set, floppy hair swept back, dressed in black trousers and a white shirt that strained at his belly. He started out with a harangue at the prisoners for wasting the court’s time.

The jeweler who had suffered the armed robbery said that three of the men, wearing balaclavas, had tied him up and held him, robbing him of an improbably large sum of money. They had shot at him with pistols but missed. A defense lawyer asked him why no bullets or bullet holes had been found in the room. The jeweler supposed rather weakly that the bullets had gone out the window. As he was allegedly tied up on the floor at the time, the defendants must have been very bad shots indeed. The defense lawyer was making hay with this.

The judge had been ostentatiously not listening whenever the defense spoke, whittling at his fingernails with his knife or chatting with the rapporteur, who equally stopped writing whenever the defense said anything. But somehow it must have penetrated the judge’s thick skin that this prosecution witness was not going down well. He interrupted the defense lawyer with a sharp rebuke, and then instructed the defendants to stand.

He harangued them again, saying that they represented evil in society. They were thieves and murderers who sought to undermine Uzbekistan’s independence and democracy. Their list of crimes was long and it would be better if they admitted it. He concluded that he was astonished that they had found the time to commit so many crimes, when they had to stop to pray five times a day. He evidently considered this a hilarioussally and guffawed loudly, as did the prosecutor, rapporteur and various other cronies. But I noticed a few narrowed eyes among the militiamen. Later he again amused himself hugely by interrupting a defendant: “I don’t suppose anyone could hear you through your long Muslim beard,” snapped the judge. “I see the prison service removed it for you!” He several times told the defense to shut up and stop wasting time.1

The jeweler was asked to identify which three of the six had robbed him. He peered uncertainly at the benches—plainly he had no idea. Pressed by the defense, he managed to identify—and the odds against this must be high—entirely the wrong three. This got the judge very angry.

“You are mistaken, you old fool!” he bellowed.

The judge then read out the names of the three who were charged with this particular crime, and asked them to stand.

“Are these the men?” he asked the terrified jeweler, who stammered his assent.

“Let the record show they were positively identified by the victim,” said the judge.

This was pure farce, but I had to pull myself back to the terrible reality behind this bizarre charade. These six nervous men stood to be shot. The family would not be informed of the execution, so for months would not know if their loved one was dead, believing him perhaps dead while he still languished, and perhaps alive when he was well rotted. This was a deliberately refined cruelty as was the practice—inherited from the Soviets—that when the family was finally informed of the death, they would be charged for the bullets that killed him.

It was at this minute I was caught by those eyes I will never forget—they were Khuderbegainov’s. He had spotted me in the crowd, a Westerner in a three-piece suit, out of place and time. Who was I? Maybe this strange apparition brought some kind of hope. Maybe the West would do something. Maybe he wasn’t going to die after all. The drowning man had caught a fleeting glimpse of straw on the surface. His eyes bored into mine, small, dark, intense, filled with a desperate hope. He was urging me, with every mute fiber of his being, to do something. I looked back. I don’t do telepathy, but stared at him, trying to say: “I will try, in God’s name, I will try,” with my own eyes. He smiled and nodded, a confidence shared, and then looked away again.

Again, I suffered a wave of self-loathing: What am I doing here? What right have I to give false hope—is that not just one more cruelty?

BUT THIS MOMENTARY doubt was replaced by an iron resolve—I would help; I would work tirelessly to stop this horror in Uzbekistan. I would not spend three years on the golf course and cocktail circuit. I would not go along with political lies or leave the truth unspoken. The next bit of the trial set that resolve, like catalyst added to epoxy resin.

An old man was assisted to the witness stand. He had a little white beard and sparse white hair, and wore a black lacquered skullcap and a dull brown quilted gown. He was shaking with fright. One of the accused was his nephew. His statement was read out to him, in which he confirmed that his nephew was a terrorist who stole money to send to Osama bin Laden, and had traveled to Afghanistan to meet Bin Laden.

“Is this your testimony?” asked the prosecutor.

“But it’s not true,” replied the old man. “They tortured me to say it.”

The judge said that accusations of torture had been dismissed earlier in the case. They could not be reintroduced.

“But they tortured me!” said the old man. “They tortured my grandson before my eyes. They beat his testicles and put electrodes on his body. They put a mask on him to stop him breathing. They raped him with a bottle. Then they brought my granddaughter and said they would rape her. All the time they said, ‘Osama bin Laden, Osama bin Laden.’ We are poor farmers from Andijon. We are good Muslims, but what do we know of Osama bin Laden?”

His quavering voice had become stronger, but at this he physically collapsed and was helped out. The judge then stated that the prisoners’ connection with Osama bin Laden was not in doubt. They had confessed to it.

I had seen enough and left. Those three hours in court had a profound effect on me. If these were our allies in the War on Terror, we were not on the clear moral ground that Blair and Bush claimed so braggingly.

I SENT A TELEGRAM back to London, explaining in detail what I had seen at the trial. Shortly thereafter, a sentence of death was passed on Khuderbegainov and long sentences given to his “accomplices.” The Human Rights Policy Department in the FCO agreed we should take up the case, and the wheels clunked into motion for the long process of agreeing to an EU démarche, or formal protest.

In the meantime, Dilobar and her father came to my office. I welcomed them, accepted their thanks for attending the trial and said that I had been shocked by what I saw. I asked the father what they could tell me by way of background to the trial.

This was the first time I had encountered a phenomenon that was to bedevil me for the next two years: the inability of Uzbeks in human rights cases to tell their story in a plain, concise manner. This is well recognized by those working in the field. Various reasons are given—sheer terror at saying anything against the government, the effect of social shaming and the cultural propensity for roundabout storytelling. But the phenomenon is very real, and frustrating.

The Khuderbegainovs, a well-established Tashkent family, were previously in favor with the regime. The father was a former head of a Tashkent state radio station. He told me the story of when he had been arrested for questioning. They came for him while he was attending a family wedding. He was in tears as he told this, and seemed unable to get past his despair at being arrested in such a humiliatingly public fashion, and his astonishment that a wedding should be violated.

Weddings hold an important position in most cultures, but Uzbek society takes this to extremes, with a family not infrequently spending three years’ income on a daughter’s wedding. So no doubt it is very bad form to violate one. But the poor man, holding back his tears, had spent thirty minutes telling me nothing but that he had been arrested at a wedding. With his son sentenced to death, this was hardly the most important point.

I therefore asked Dilobar to continue the story. I learned from her that her brother had received an education at one of the Saudi-funded Arabic schools opened in Tashkent in the 1990s. Following the bombings there in 1999,2 these schools were closed down and many of their pupils and former pupils imprisoned. Eventually this well-connected family received warning that her brother was to be arrested, and he ran away to Tajikistan, where he made contact with rebel groups. From there he was sent to Afghanistan to fight with the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) alongside the Taliban, but he didn’t like what he saw and ran away from there too.

For a year he scratched out a living as a bazaar trader before eventually being arrested crossing the Tajik/Uzbek border. He was then imprisoned for some months in Uzbekistan and severely tortured, which had caused permanent liver damage. Under torture he had confessed to the range of crimes featured in the trial. The family had not known he was taken until the trial began. During the period of imprisonment, the father himself was imprisoned. His brutal interrogation ostensibly focused on the whereabouts of his son, who in fact was already in custody at the time.

I judged that Dilobar believed this story herself. I wondered whether this was the whole truth about Khuderbegainov’s involvement with the IMU and the Taliban, but even if it wasn’t, he plainly had not received a fair trial on the charges for which he had been sentenced to death. I thanked the impressively composed and articulate Dilobar and her father, and promised to do what I could. We had already decided to move for an EU démarche, but I was racking my brains for further action that might forestall the execution, and decided to contact the UN.

THE NEXT DAY Chris came into my office and tossed a brown envelope onto my desk.

“You may not want to look at these—they’re pretty horrible,” he said.

I was beginning to understand enough about the country to have an inkling what might be in the envelope, and I waited until the cook, Galina, had brought in my cappuccino and biscuits before opening it. It contained a number of photos of a naked corpse, a heavy, middle-aged man. His face was bruised and bloodied, and his torso and limbs were swollen and a livid purple. He was such a mess that it took a little while for me to work out what I was looking at. I said a short prayer, rather to my own surprise.

I then went back through to Chris’s office.

“Where did we get these?”

“His mother. That’s Mr. Avazov. He was a prisoner in Jaslyk gulag, right up in the desert. That’s where they take the hard-line dissidents. Anyway, his body gets delivered back to his mum in a sealed metal casket. She’s ordered not to open it and to bury it the next day. A local militsiya is left to guard it. Anyway, militsiya man falls asleep and Mum sneaks down, gets the casket open, body onto the kitchen table, and gets out the Kodak.”

“Without waking up the militsiya man?”

“He was probably drunk.”

“Look, Chris, I don’t know what happened to this poor bugger, but I think we should go big on this one. I really want to get serious with this regime, and this could be the case we need. But we have to be certain of our ground.”

Chris mused, “The photos are pretty good. I am sure Alistair in Human Rights Policy Department in London said that they could get pathology reports done, if they had good enough photos.”

“Great. Try it.”

MY APPEARANCE AT the Khuderbegainov trial had caused quite a stir. Ambassadors in Tashkent just did not attend dissident trials. It brought Matilda Bogner, head of the local office of Human Rights Watch, to the embassy to see me. Matilda was a pleasant Australian in her early thirties, with a broad open face, long brown hair swept back into a ponytail and a penchant for peasant dresses.

“They tell me that you’re not like a normal ambassador,” she opened.

“I certainly hope not,” I replied. “I am struggling to work out what this embassy actually used to do all day.”

“Not a lot,” she said. “Chris is good, but I think he was pretty well frustrated.”

She filled me in on the human rights situation, and it was grim. No opposition parties, no free media, no freedom of assembly, no freedom of religion, no freedom of movement. Not only were exit visas required to leave the country, you needed an internal visa or propusk in your passport just to leave the town where you lived. Matilda reckoned there were, at an absolute minimum, seven thousand people imprisoned for their religious or political beliefs. She filled me in on the cases of Elena Urlaeva and Larisa Vdovina, who had recently been committed to a lunatic asylum for demonstrating outside the parliament. Both were now strapped to their beds and receiving drug treatment that amounted to a chemical lobotomy.

I thanked Matilda, and said I hoped we would be able to work closely together. I asked her about the attitude of other embassies. She said the U.S. embassy was in denial. It viewed President Karimov as an essential partner in the War on Terror, and had convinced itself that he was a democrat. Of the other embassies, only the Swiss really gave a stuff about human rights. Unfortunately, the countries that genuinely cared about human rights—the Scandinavians, Dutch, Irish, Canadians and Australians—didn’t have embassies in Uzbekistan.

A FORTNIGHT LATER, Chris received the report on the photos of the corpse of Mr. Avazov. The pathology department of the University of Glasgow had prepared a brief but detailed report of their findings. The victim had died of immersion in boiling liquid. It was immersion rather than splashing because there was a clear tidemark around the upper torso and upper arms, with 100 percent scalding underneath. Before he was boiled to death, his fingernails had been ripped out and he had been severely beaten around the face. Reading the dispassionate language of the pathology report, I was struck with a cold horror.

© 2006 Craig Murray

Product Details

- Publisher: Scribner (April 2, 2011)

- Length: 384 pages

- ISBN13: 9781416548027

Browse Related Books

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Dirty Diplomacy Trade Paperback 9781416548027

- Author Photo (jpg): Craig Murray Photo Credit:(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit